There was an interesting, if minor, piece of fallout from the clashing protests that occurred around the country last week when former Cold Chisel singer Jimmy Barnes told the Reclaim Australia demonstrators, who had been playing one of the band’s signature tunes ‘Khe Sanh’ at their rallies, that he did not want them using his music (which is not exactly ‘his’, as the Guardian would have it, since ‘Khe Sanh’ was written by band’s pianist and principal songwriter Don Walker). John Farnham then came out and told them they could stop playing his song ‘You’re the Voice’ as well – we can only hope that others also take heed. The rebuff was a crowning humiliation for Reclaim Australia, whose rallies were such a disaster that one could almost feel sorry for them were it not for the poisonous garbage they espouse. It takes a special kind of moron to deny racism and call for an end to all ‘non white immigration’ on the same placard.

The widely-praised reactions of Barnes and Farnham have prompted some interesting reflections on the relationship between music and politics. Liam Viney in the Conversation has analysed the lyrics, melody and structure of ‘Khe Sanh’ to try to account for the song’s emotional pull and assess its appropriateness as a song of ‘protest’. The Brisbane-based music critic Andrew Stafford wrote an article, in which he drew a parallel with the numerous failed attempts by the Republican Party in the US to co-opt the music of ‘heartland’ rockers like Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty and Neil Young. The Sydney Morning Herald’s music critic Bernard Zuel also compiled a survey of some unsuccessful attempts by politicians to associate themselves with popular musicians.

For the most part, the interactions between politicians and musicians have resulted in little more than amusing moments of incomprehension and absurdity. When conservative British Prime Minister David Cameron claimed to like the music of the Smiths, guitarist and songwriter Johnny Marr, a working-class Mancunian, shot back: ‘No you don’t. I forbid you to like it.’ Cameron – an Eton Old Boy – has also named the Jam’s ‘Eton Rifles’ as one of his favourite songs, prompting the song’s composer Paul Weller to retort: ‘Which bit didn’t you get? … It wasn’t intended as a fucking jolly drinking song for the cadet corp.’ Cameron said that he didn’t see why ‘the left should be the only ones allowed to listen to protest songs’ – overlooking the fact that his professed fondness for ‘Eton Rifles’ is akin to Her Majesty claiming to be a big fan of the the Smiths’ ‘The Queen is Dead’ or the Sex Pistols’ ‘God Save the Queen’ (whose line about the ‘fascist regime’ received a bit of a twist this week).

Such byplay tends to reveal that politicians are often music ‘fans’ in a rather qualified sense. Cameron’s Labour predecessor Gordon Brown once claimed to like the Arctic Monkeys, but when pressed was unable to name a single one of their songs. Former Australian Prime Minister John Howard has professed his fondness for Bob Dylan, yet managed somehow to give the odd impression that he was unaware not only that Dylan no longer writes ‘protest’ songs or has a thing with Joan Baez, but that he has, in fact, gone electric. Howard was careful to specify that he liked Dylan’s music but not his ‘message’, though I have not the faintest idea what he could find objectionable about the perfectly reasonable injunction to ‘keep a good head and always carry a lightbulb’. His stated admiration for Dylan is at least more credible than his wildly implausible claim that his favourite Midnight Oil song is ‘Beds are Burning’.

There is, of course, a significant difference between professional politicians trying to associate themselves with something popular and a group of demonstrators singing a song they genuinely think represents them. Once a song, or indeed any work of art, is absorbed into the wider culture, it accrues meanings beyond the literal or the intended. Songs can, of course, be misinterpreted and misappropriated in genuinely obnoxious ways: Joe Strummer is said to have wept when he heard that US soldiers in the first Iraq war had adopted the Clash’s ‘Rock the Casbah’ as an anthem; I can well remember a group of boys from my country-town high school using Goanna’s pro-land rights song ‘Solid Rock’ to taunt Aboriginal students, shouting the line ‘white man, white law, white gun’ followed by a ‘bang’. This is not what was going on at the Reclaim Australia protests, I don’t think. And it is why analysing the structure of ‘Khe Sanh’ or the observing that the protesters may not have grasped the subtleties of Don Walker’s lyrics is to miss the point entirely, since the song was clearly being sung as an expression of identity.

The enormous and enduring popularity of Cold Chisel among blue-collar and rural Australians would make a truly fascinating case study for Pierre Bourdieu’s theory that taste is a marker of class. No doubt part of the reason for that popularity is Walker’s ability to write about working- and in some cases criminal-class characters without condescension. Nor is it a coincidence that Cold Chisel’s most revered songs – ‘Khe Sanh’, ‘Cheap Wine’, ‘Flame Trees’ – are about disaffection, marginalisation, aimlessness, alcoholic indolence and small-town inertia. In documenting these travails, Cold Chisel has also come to represent them. The literal meanings of the songs have long ceased to be as important than the band’s symbolic status: they have acquired a cultural meaning that is independent of the actual qualities of the songs themselves. I have friends who cannot bear to listen to Cold Chisel purely because the band is associated in their minds (with some justification) with a certain kind of drunken loutishness. There is a kind of irony, though not a surprising one, in the fact that, having perfectly encapsulated in ‘Flame Trees’ the peculiar stasis and insularity of small-town life, one of the things that never changes in those towns is that Cold Chisel is always on the jukebox. And if part of the sense of identification that Cold Chisel inspires is recognition, and if we do want to try to understand why some people should feel so threatened by difference, so filled with such irrational and ill-directed hatred and fear, then Walker may well have pithily encapsulated that too:

I’m standing on the outside looking in

Room full of money and the born to win

And no amount of work’s gonna get me through the door.

This week Sydney Review of Books features a timely essay by Andrew Jakubowicz. In ‘The Wall of Race’ , Jakubowicz examines Klaus Neumann’s new history Across the Seas, which details Australia’s responses to refugees from Federation through to the 1970s. From the outset, Jakubowicz argues, Australia’s immigration policies have been shaped by the question of race, as governments of all persuasions have operated on the assumption that they should maintain control over the make-up of the population:

Neumann intends, as he says, to deploy ‘the narratives of the past to unsettle ideas about the present’. His examples show just how much the public perception of refuge-seekers depends on the cultural interpretations generated by governments, and reinterpreted and circulated by the media. In particular, he argues that perceived national interests, or the political interests of the national government, set out the primary parameters within which policies are developed and actions are taken.

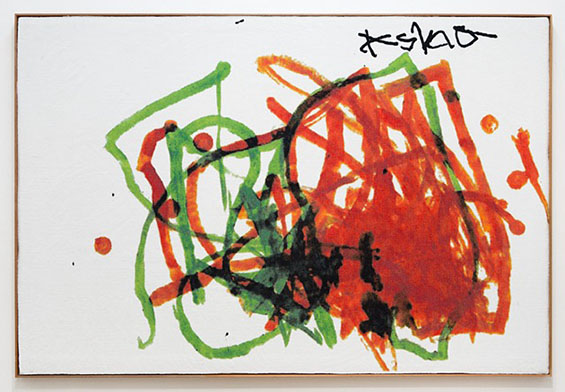

Our second essay is Martin Edmond’s review of Sidney Nolan: A Life by Nancy Underhill. Nolan was a man characterised by his ‘insouciance … dark humour and a devil-may-care refusal to be weighed down by the consequences of actions that may have been foolish or worse’. A major figure in Australian art, Nolan created some of its most famous and enduring images in his series of paintings based on the exploits of Ned Kelly, an early achievement that has tended to overshadow his subsequent work. Edmond argues that Nolan deserves to be the subject of a comprehensive biography, but Underhill’s account, he finds, has some serious flaws:

A biographer has to be able to order information and then present it clearly and comprehensibly: this book does neither. There is no clarity to the exposition and, more seriously, no over-arching theme or real insight into the character of its subject.

From the Archives this week looks back at an essay that complements Jakubowicz’s examination of Australia’s refugee history. In ‘Between Bad and Worse’, Michelle Foster reflects on Australia’s obligations under international law and the toxic politics that has come to surround the issue of asylum seekers.