At the end of August I was invited to attend the Sino-Foreign Literature Translation and Publishing Workshop hosted by the Chinese Ministry of Culture and Lu Xun Academy. The timing was perfect – China was celebrating 70 years of victory over the Japanese (or Japanese capitulation depending on which news outlet you follow) and to ensure clear skies for the massive parade, factories around the capital were shut down weeks in advance and the rules on when Beijingers could drive were tightened further. All these measures meant that the sky was clear – I even saw my first Beijing sunset, despite having previously spent over three weeks in the capital on two separate trips.

Participants, most of whom were Sinologists, translators or both, came from all over – there were Dutch, Mexicans, a South African and Russians, inter alia, and we all gathered at a five star hotel for lectures and information sharing.

In one of the sessions, a young academic from Beijing Normal University outlined the three steps one needs to follow to understand classical Chinese poetry.

1. Read the poem carefully.

2. Compare poems that cover similar topics or have matching themes.

3. Consider the historical context.

If you follow these steps, he assured us, we would understand classical Chinese poetry.

For the contemporary literary culture, I can offer no such tidy scheme.

With its vast disparities in wealth, its complicated political and economic systems (not to mention dialects and diverse customs) the world’s second most populous country doesn’t lend itself to a tidy system of analysis. Yes, the steps listed above for understanding poetry would be a good start – close reading and concern for themes and context are valuable tools for considering fiction but they are only the beginning. Notably, they do not include a device that I think is part critical faculty and part of the basis for the pleasure in reading fiction – personal response.

Further, I think there is value in using contemporary literature, and novels in particular, as tools to help us understand historical context. China is changing so rapidly that fiction with characters from different generations efficiently communicates the pace of change, the effects of history and the prospects for the future.

Consider the reception for Eastern versus Western books in the local market. An Australian reader might know some of the greats of Italian literature and have a sense of Italian history – besides which we are familiar with Italian food and customs. Add in some alignment of aesthetic sensibilities and a contemporary Italian novel in translation is relatively easy to access: think Elena Ferrante. (As an aside, a heated conversation in one of the sessions revolved around how translators should deal with regional specialities – whether they should find equivalents in the cuisine of the target language’s people, whether there should be a footnote or a brief explanation following the transliteration of the dish. The third option seemed to be the most popular.) Many of these social and cultural frames are missing for local readers of non-Chinese heritage and to further complicate the process, the understanding of recent history inside and outside China is very different.

As an additional obstacle, there are the major discrepancies in the publishing processes which mean that Chinese novels often seem different in kind from their Western counterparts. Just to take two examples, in the past few months I have read The Seventh Day by Yu Hua and Massage by Bi Feiyu. Neither follows the sort of narrative arc that an editor in an Australian trade publisher would encourage but each is compelling for character development, cultural insights and sense of humour – I’ve heard it said more than once that the closest cultural tie for Australians and Chinese is our shared laconic sense of humour.

What the translators from all over the world all agreed on was that studying Chinese literature helped them reach an understanding about China that they couldn’t reach with history, politics or anthropology. That the careful work of trying to bring ideas, characters, settings and jokes into a target language requires a full gamut of critical thinking and emotional intelligence. That the work of translation is about so much more than simply bringing entertainment from one language to another.

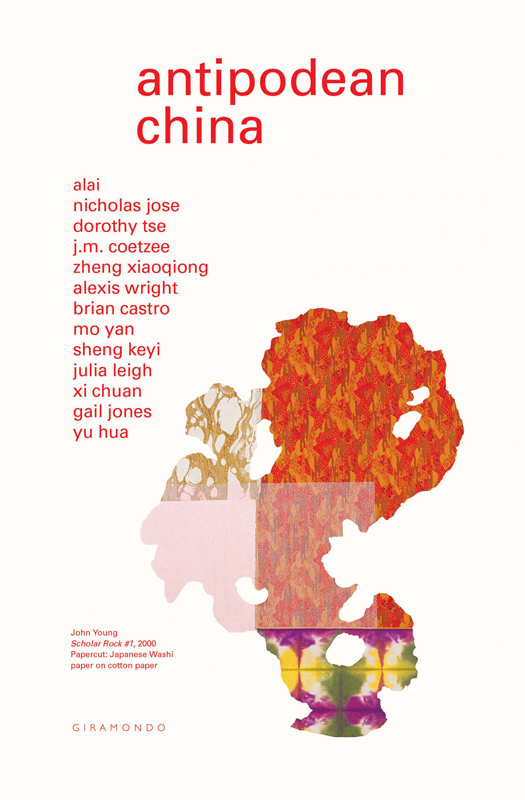

At a time when negotiations are underway for the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement and Australia is potentially developing even closer ties with one of the world’s super-powers, may I recommend getting to know the country and its people better through their literature, even if the progress is slow and at times alienating. And from the other side, it’s just as important for Australia to infiltrate China with our best writers. The Chinese government’s program of ‘soft power’ is partly behind the significant funding to cover the costs of translation – an expensive and laborious process. The cuts to arts funding in Australia, however, mean that there will likely be less money available for the translation of local literary works into other languages – including Mandarin – and that will ultimately make it more difficult for us to get to know each other.

A new translation of the Iliad by Peter Green is the occasion for an essay on Simone Weil and Homer by Peter Salmon. In the winter of 1940, during the first months of the Nazi occupation of France, the analogies between the world of the Iliad and the situation in Europe were, as Salmon writes, both striking and chilling to Weil:

There were broken truces, a city under siege, and failed attempts to appease one man’s wrath. That Troy was destined to be sacked seemed inevitable, and that the Gods were dispensing justice that was fickle at best and arbitrary at worst, equally so. For Weil, waiting for an exit visa with a battered copy of the Iliad in her rucksack in case she was arrested, Homer’s great epic – now available in a gripping and muscular new translation by Peter Green – seemed to be completely of the moment.

Although critical essays on literature remain at the centre of the SRB’s field of activity we are committed to mapping new possibilities for the essay form. In our second essay this week, the first installment of a two-part account of drug addiction, Chris Fleming blends memoir, reportage and ethnography to explore the modes, mechanics, and madness of legal and illegal drug acquisition.

It wore on my nerves never knowing whether Ed would be home or not, and if so, how long he’d give me to get to his place before he disappeared; I found intolerable the fundamental uncontrollability of securing what I saw as an absolutely necessity. At one point Ed even chastised me for coming around too often. It was hard to suck up to someone who would insult you for a range of things, including buying too many drugs from him.

Finally this week we are pleased to publish a talk given earlier this month by the artist Bronwyn Bancroft on the present situation of the Aboriginal Artist. She writes:

My name is Bronwyn Bancroft and I am a Bundjalung Nation woman from Northern New South Wales. My Father was Aboriginal and my Mother is Polish and Scottish.

I am an Artist. In my role as an Artist I see an obligation through my art to make a difference. I stand up for change in relation to issues that confront me in the society that I live in today.

The title of this paper is ‘Being an Aboriginal Artist is not a Lifestyle Choice’. I knew that statement by the Prime Minister was politically inflammatory and as such I had a perfect hook to get you reading. This is the first step in creating participation and promoting experiences. I hope to explore here the essence of what it is to be human and how we may be able to explore this story through the viewfinder of one person’s life.

The SRB publishes letters to the editor and this week we have received responses both to Ivor Indyk’s editorial on literary prizes and to Peter Salmon’s essay on Simone Weil. You can read SRB correspondence here. Please address your correspondence to editor@sydneyreviewofbooks.com.

As the sending of this newsletter coincides with the anniversary of the bombing of the World Trade Centre in New York, From the Archive this week turns to an essay by Jeff Sparrow on the regulatory environment that emerged in post-9/11 Australia.

The Terrorism Act 2002 did more than rebrand old offences with the post 9/11 lexicon. As Andrew Lynch, Nicola McGarrity and George Williams explain in Inside Australia’s Anti-Terrorism Laws and Trials, the legislation brought into being a raft of so-called ‘preparatory offences’, so that it became a crime to provide or receive training, to possess a ‘thing’, or to collect or make a document, if (in each case) that conduct was ‘connected with preparation for, the engagement of a person in, or assistance in a terrorist act’.