The two Australian surfers disappeared and presumed dead in Sinaloa are part of a much larger pattern of violence, death and impunity that has emerged in Mexico over the last nine years. There were murders and impunity in Mexico prior to 2006 but in that year President Felipe Calderon began his crusade against certain cartels and unleashed a tide of violence that is still sweeping the country.

Raw numbers can give us some idea of the human suffering involved. We can add the two Australians to the 43 student teachers forcefully disappeared by the municipal police in the town of Iguala in 2014, the 24,000 plus missing people and around 120,000 people dead since 2006. These numbers are both staggering and numbing. The sheer scale of the human tragedy is difficult to comprehend – which is why it has become important for so many people in Mexico to name the victims and to tell their stories.

Dean Lucas and Adam Coleman: the names of the two Australians presumed dead in Sinaloa. The stories of these men are being told because they are conspicuous as white men from the first world in a sea of third world death and despair. Their stories should be told, along with those of the tens of thousands of others who are the victims of the drug war and the violence it has normalised. These stories should be told, not to warn people, but because telling the stories of the victims of murder restores the dignity that was robbed from them when they were killed.

This dignity begins with identification of bodies and the thorough investigation of the circumstances of death. Only around 4% of homicides in Mexico are investigated and only 2% of cases are ever solved. The numbers for Sinaloa are even worse with over 99% of murders unsolved. It’s not surprising that Mexicans have little faith in a criminal justice system that is both corrupt and demonstrably ineffectual. The lack of faith of the Mexican people in their government and institutions has been expressed by Dean Lucas’ Mexican girlfriend Andrea Gomez:

This [violence] is so common in Mexico, it happens every day. It doesn’t surprise me, but for the family of the boys it is so out of the normal to hear about these things and so sad that he will remain here and they’ll never find those responsible.

In my heart I will get justice for them. I will. The government will never get justice for them.

So I will resign myself to that to protect myself.

Every effort is being made to identify the bodies of Dean Lucas and Adam Coleman. Their deaths will be investigated – in some way. Given the international attention to this case it would also seem likely that the authorities will find someone who they can claim was responsible for their deaths. However – as Andrea Gomez’s comments indicate – the claims of Mexican authorities should be met with scepticism. It has become standard procedure for Mexican police to base the few convictions that they do attain on confessions – often extracted through torture – while neglecting the process of gathering physical evidence that would be required to build a proper case in many jurisdictions.

In the absence of justice the process of naming the victims gives them the small dignity of not simply being another number in what are already harrowing statistics. And where the task of naming the tens of thousands of dead and disappeared is perhaps too much, 43 names have become emblematic of the struggle for justice in Mexico – the names of the student teachers forcefully disappeared by the municipal police, with the complicity of the federal police and the army, in the town of Iguala, Guerrero, Mexico on 26 September 2014. For this reason, alongside the two Australians – Dean Lucas and Adam Coleman – we should name at least 43 Mexicans; Alexander Mora Venancio, Jhosivani Guerrero de la Cruz, Abel García Hernández, Abelardo Vázquez Peniten, Adán Abrajan de la Cruz, Antonio Santana Maestro, Benjamín Ascencio Bautista, Bernardo Flores Alcaraz, Carlos Iván Ramírez Villarreal, Carlos Lorenzo Hernández Muñoz, César Manuel González Hernández, Christian Alfonso Rodríguez Telumbre, Christian Tomas Colón Garnica, Cutberto Ortiz Ramos, Dorian González Parral, Emiliano Alen Gaspar de la Cruz, Everardo Rodríguez Bello, Felipe Arnulfo Rosas, Giovanni Galindes Guerrero, Israel Caballero Sánchez, Israel Jacinto Lugardo, Jesús Jovany Rodríguez Tlatempa, Jonas Trujillo González, Jorge Álvarez Nava, Jorge Aníbal Cruz Mendoza, Jorge Antonio Tizapa Legideño, Jorge Luis González Parral, José Ángel Campos Cantor, José Ángel Navarrete González, José Eduardo Bartolo Tlatempa, José Luís Luna Torres, Julio César López Patolzin, Leonel Castro Abarca, Luis Ángel Abarca Carrillo, Luis Ángel Francisco Arzola, Magdaleno Rubén Lauro Villegas, Marcial Pablo Baranda, Marco Antonio Gómez Molina, Martín Getsemany Sánchez García, Mauricio Ortega Valerio, Miguel Ángel Hernández Martínez, Miguel Ángel Mendoza Zacarías and Saúl Bruno García.

Knowing these names is the first step in restoring human dignity in this case. While we can recite the names, over a year after their disappearance, we still cannot know with any certainty the fate of 41 of the 43 missing students. The remains of Alexander Mora Venancio and Jhosivani Guerrero de la Cruz have been identified. There is now an official version of events provided by the government that relies heavily on the confessions of perpetrators to suggest that the bodies of the remaining 41 students were completely incinerated and therefore impossible to identify. The families, surviving students and a team of experts appointed by the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights insist that the investigation was flawed. They argue that there are numerous reasons to continue investigating and searching for the missing students including the involvement of the army in the crime (something that was never properly investigated), the lack of physical evidence and doubts regarding the capacity of the fire to reach the temperature required to fully incinerate the bodies.

Luis Angel Abarca Carrillo. Photo: Antonio Diaz. From the exhibition 43 reflections for Ayotzinapa documenting protests in Mexico City. Each of the 43 photographs is titled with the name of one of the missing students.

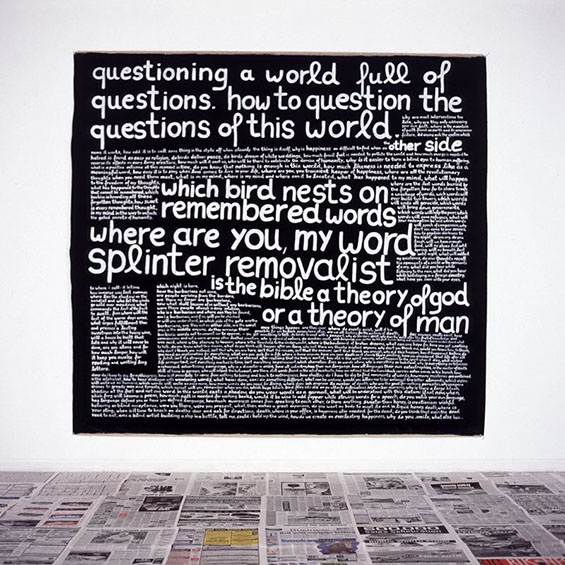

The names of the 43 victims have been read at the protests across Mexico and around the world that were sparked by their disappearance, but this process of naming to honour the victims of the drug war has been going on for much longer. When Felipe Calderón left office in 2012 the families of the victims of his war, along with activists, began to embroider thousands of names – in red thread on white handkerchiefs for the dead and in green for the disappeared – in an action that turns the act of naming into a slow, attentive memorialising of a single victim of the war on drugs;

Leticia Hidalgo Rea arrives at seven in the afternoon. Carefully she stretches a clothesline to hold each of the handkerchiefs with clothes pins. She opens her sewing box and takes out embroidery hoop, green yarn and needle. Standing, she caresses the fabric where ‘Roy’ is written, the name of her son who disappeared twenty months ago. She measures and inserts the needle to begin the horizontal stitch; each stitch holds compassion, tenderness, catharsis, tears, hope, peace.

To paraphrase Andrea Gomez’s words these rituals of naming can become a way to find justice in our hearts when the Mexican government and its institutions have failed so grievously. The naming of victims – or of objects and details surrounding the victim’s deaths in the case where they could not be identified – is also a crucial aspect of the 2002 book Huesos en el desierto, an investigation of femicides in Ciudad Juarez by journalist Sergio González Rodríguez, and the fictionalising of this material by Roberto Bolaño in 2666. While he changed the names Bolaño drew on many important details and the dates of specific femicides in Ciudad Juarez (the city that becomes Santa Teresa in his work). The correspondence between the actual femicides and how they are depicted in ‘The Part About the Crimes’ in 2666 has been summarised by Chris Andrews in the appendix to his book Roberto Bolaño’s Fiction: An Expanding Universe. He notes that

The most significant detail revealed by the comparison of the real and fictional cases is that if we include Perla Beatriz Ochoterena among the fictional victims (since her suicide is connected to the murders: she leaves a note referring to “all those dead girls”), their number exactly matches that of the real victims in Juárez in the years 1993–1997 as recorded in Huesos en el desierto.

While Roberto Bolaño did not live to see the current wave of violence that has engulfed Mexico the urgency of the task that he set for himself in 2666 has only increased. The task of naming and telling these stories has been taken up by novelists, artists and activists partly because Mexico is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist and very little of the violence that occurs there is reported by the media. The process of naming and storytelling matters because without it so many victims, whose cases will never be solved, would at best be aggregated into the numbers of deaths and disappearances.

The names of the 43 missing students continue to resonate because nothing has changed structurally to push back the tide of violence. The state cannot offer the families and surviving students the basic human dignity of knowing the circumstances surrounding the disappearance of their children and classmates because it has so comprehensively failed to provide the basic justice and security that are its core function. Politics and the armed forces in Mexico are so completely mired in the corruption of the drug trade (and other forms of corruption that include the current President Enrique Peña Nieto) that there can be little faith in the institutions and pronouncements of the Mexican government. This corruption and impunity is partly a problem of the scale of the drug trade. The state of Sinaloa – home of the Sinaloa cartel run by Chapo Guzmán, whose territory Dean Lucas and Adam Coleman were traveling through – accounts for around half of the trade. The US justice department estimate ‘that Colombian and Mexican cartels reap $18 billion to $39 billion from drug sales in the United States each year.’ More conservative estimates suggest

the gross revenue that all Mexican cartels derive from exporting drugs to the United States amounts to […] $6.6 billion’. By most estimates, though, Sinaloa has achieved a market share of at least 40 percent and perhaps as much as 60 percent, which means that Chapo Guzmán’s organization would appear to enjoy annual revenues of some $3 billion — comparable in terms of earnings to Netflix or, for that matter, to Facebook. (Cocaine Incorporated, New York Times Magazine)

The case of the Sinaloa cartel and Chapo Guzmán is emblematic of another aspect of Mexico’s failed institutions. If he wasn’t the head of a murderous cartel Chapo’s story would be comical. He has been captured and managed to escape from maximum security prison twice – most recently this year, after his capture in 2014 – and even while in jail he was seemingly able to continue living the high life, running his empire from prison with the help of his brother Arturo Guzmán Loera. The fact that Chapo is able to pull the strings of Mexican institutions in the way that he has is evidence of the complete corruptibility of the Mexican criminal justice system. Chapo Guzmán’s capture in 2014 was greeted with much fanfare by the Mexican government. Many Mexicans viewed his subsequent escape as simply inevitable.

In his 2015 book Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs and in many interviews Johann Hari argues convincingly that the violence that has become a way of life in Mexico is a direct consequence of drug prohibition. When you deal in an illegal substance and have no recourse to the police if someone steals your product the only way to protect your business is to demonstrate to your competitors that you are more violent and ruthless than they are. Cracking down on cartels has made this situation worse. Calderon’s crusade has triggered turf wars that have in turn led to the unspeakable horrors perpetrated by Mexican cartels.

At this stage there has been no suggestion that Dean Lucas and Adam Coleman were in any way linked to the drug trade. However it is the war on drugs – our war on drugs, (the Sinaloa Cartel is believed to be a major supplier of cocaine to Australia) – that has created the structural conditions in Mexico that make murders like those of Dean Lucas and Adam Coleman an everyday occurrence. Prohibition has transferred one of the most lucrative businesses on the planet to the hands of brutal criminal armies. Chapo Guzmán is the general of one of those armies. He is also effectively the CEO of one of Mexico’s largest multinational corporations. Chapo Guzmán would undoubtedly be one the foremost advocates for maintaining prohibition because he gains the most from its continuation.

The scale and resources of these narco armies, with their billions of dollars in drug revenue, has allowed them to diversify their interests to the point where 78% of the Mexican economy has reportedly been infiltrated by the cartels. Given this statistic it is hardly surprising that politicians – like the mayor of Iguala, José Luis Abarca Velázquez, who was accused by the government of playing a role in the disappearance of the 43 students – are also on their payroll and often only come to power by doing deals with the local narcos and cartels. Given the depth of corruption it would be naïve to think that ending the drug war would fix all of the problems that Mexico faces. It would, however, deprive cartels of their main source of income and therefore reduce their ability to peddle influence and wield power. It would also remove the cover that drug-related violence has created for other forms of paramilitary activity that have targeted the poor and social movements.

Johann Hari provides us with a compelling alternative to the extreme violence and chaos that the drug war has unleashed on Mexico. Instead of allowing criminal gangs to accumulate vast financial resources from this incredibly lucrative trade – by selling unknown substances to unknown individuals in completely unregulated deals – we establish true law and order by legalising and heavily regulating those drugs that are currently causing harm. As Hari notes Switzerland has done this with heroin and it has been an overwhelming success. We must stop thinking of this issue along the lines of the false dichotomy of good drug warriors versus evil drugs and instead recognise that the most important axis of the drug debate is harm versus healing. This applies both to individuals, from addicts to musicians to surfers to student teachers, and to societies as a whole. Drug prohibition continues to cause incredible harm and has done little to nothing by way of healing. In order to honour the names of all of the victims, to begin the process of healing and to help restore law and order to Mexico, the drug war must end.

Our first essay this week, ‘What The Essayist Spills’, is by Maria Tumarkin, and takes the essay itself as its topic. Through a reading of Meghan Daum’s The Unspeakable Tumarkin reflects on the current fortunes of the essay, especially in Australia:

I am not about to veer into a survey essay. Survey essays bore me, and you hurt people, and because it is an essay on essays you would have to talk about Montaigne, just like with essays on memoirs you have to talk about St Augustine. The question I am asking is turned outwards, to fellow writers and readers, to publishers, agents, critics, literary festival organisers, academics, booksellers – how are we travelling?…

To be clear, what is at issue here are not themed or best-of collections by multiple authors but books of essays by just one girl or guy, books which are held together not by a narrative but by a sensibility, or a consciousness, or a voice, or way of moving through the world. Some Australian publishers will put out a single essay as a standalone booklet. There are Black Inc.’s Quarterly Essays and its new Short Blacks (though they’re old pieces); Penguin has Penguin Specials; MUP had that ‘On’ series of essays; Giramondo has Giramondo Shorts (chiefly fiction, but not only). But I know for a fact that good publishers in this country will start wrapping up the meeting the minute someone pitches a single-authored, adult-length essay collection – they reckon it’ll tank.

The SRB Interview series continues. In her long conversation with Rachel Morley, Carmel Bird roams across the three decades of her career in Australian literature.

I wonder now what it would have been like to have gone to university classes in writing, to have done a PhD in writing etc. In Australia in the sixties there were no Creative Writing Courses. I recall that in the early eighties I was teaching French at the Melbourne Council of Adult Education – and the director asked me if I taught any other subjects too. I said I could teach people to write short stories and he said that he didn’t think anybody would be interested. I said maybe we could give it a try. So we did. I think it must have been the first short story writing course in Melbourne. (Somebody might correct me here, but I speak to the best of my knowledge.)

Finally, in From the Archive this week, we turn again to Latin America, and to Andrew McCann’s essay on two books on Roberto Bolaño, ‘Heroes, Tombs and Street Names’. He writes:

Th[e] sense of somehow finding ourselves in Bolaño’s writing is partly what accounts for the fervour with which it is read by people committed to the idea that literature is something more than a form of distraction or entertainment. In Bolaño’s work, literature is a way of being in the world, and it is the only one that really seems to matter. But that is not to say that his perspective is insular. Bolaño’s world is also one of political violence and dislocation that swirls like a vortex around a final, undiscoverable secret, a black hole, a hidden centre that anticipates an apocalyptic future already at work in the present.