Sylvia Plath’s 1963 novel The Bell Jar opens with protagonist Esther Greenwood imagining the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Tried for espionage, the Rosenbergs were found guilty of passing of ‘atomic secrets’ to the Soviet Union during the Second World War. They were killed in New York’s Sing Sing Prison in 1953, the year Plath and the fictional Esther spent time in Manhattan. Being ‘burned alive all along your nerves,’ Esther thinks, must be ‘the worst thing in the world.’

Despite an international outcry and a last-minute plea for clemency, President Eisenhower allowed no appeal. To avoid the death penalty, the Rosenbergs were offered the opportunity to confess. They refused, writing: ‘We will not help to purify the foul record of fraudulent conviction and a barbaric sentence … our respect for truth, conscience and human dignity are not for sale.’ As Julius and then Ethel Rosenberg died, the latter only after several electrocutions, the prison rabbi, Irving Koslowe, spoke the words of Psalm 23: ‘Yea, though I walk through the valley of death, I will fear no evil.’

Plath wrote The Bell Jar a decade after receiving the electroconvulsive therapy that inspired the violent electrical imagery that flashes through her writing. At the same time as Plath was hospitalised and treated in the United States, Janet Frame was in the midst of eight years in and out of mental asylums in New Zealand, where she received some two hundred ECT treatments administered without anaesthetic. As she writes in her autobiography An Angel at My Table (1984), each was ‘the equivalent, in degree of fear, to an execution’. Misdiagnosed with schizophrenia, Frame also endured the humiliations meted out by sadistic staff, some of whom mocked her with the appellation ‘Miss Educated’. Her biographer Michael King describes a night towards the end of these years when, ‘sleepless … amid the howls of the demented and the stench of urine’, the writer turned on her mattress to face the wall and, like Koslowe, spoke the words of Psalm 23 into the dark.

The day after her lonely recitation, Frame was moved to another ward where freedom arrived in a way that made her believe, forever afterwards, that someone – possibly her dead mother – was looking out for her. Just days before a scheduled leucotomy, her debut collection of short stories The Lagoon and Other Stories (1951) was awarded a major prize, the Hubert Church Memorial Award. ‘My writing saved me,’ Frame often said. There were other angels: writer Frank Sargeson drew public attention to her talent and offered practical assistance, and Stephanie Dowrick, in her role as publisher at the Women’s Press in London, motivated by ‘a useful feeling of outrage that someone so talented should be so overlooked and marginalised’, worked to ensure Frame’s continued publication. These facts are part of the Frame legend, in the same way that Plath’s ECT, second life and eventual suicide are part of hers. They are themselves recited, like frayed and salvific verses of a long-remembered prayer.

In An Angel at My Table, Frame describes her experience of mental institutions as ‘a concentrated course in the horrors of insanity and the dwelling-place of those judged insane.’ It separated her ‘forever from the former acceptable realities and assurances of everyday life.’ Her escape felt, as Plath’s did to her, like a resurrection. She writes:

I have inhabited a territory of loneliness which I think resembles that place where the dying spend their time before death, and from where those who do return living to the world bring inevitably a unique point of view that is a nightmare, a treasure, a lifelong possession; at times I think it must be the best view in the world, ranging even farther than the view from the mountains of love, equal in it rapture and chilling exposure, there in the neighbourhood of the ancient gods and goddesses.

*

It is not uncommon for writers to describe their work as posthumous. In 1820, Keats, at twenty-five, wrote to his friend Charles Brown: ‘I have an habitual feeling of my real life having past, and that I am leading a posthumous existence.’ He had less than three months to live. In a biographical note accompanying his poems in Thomas Shapcott’s 1969 anthology Australian Poetry Now, Michael Dransfield wrote: ‘I am the ghost haunting an old house, my poems are posthumous.’ Plath’s last poems, written in the weeks before her death, create the illusion of completion. In ‘Edge’, for example,

The woman is perfected.

Her deadBody wears the smile of accomplishment

While Plath intuited that she had started to write ‘the poems that will make my name’, she could hardly have imagined her posthumous fame, nor the way that her work would be freighted with others’ projections, losses and desires. Frame, on the other hand, overcame the lure of suicide to experience her own figurative posthumous flourishing – and to plan a more literal one beyond that.

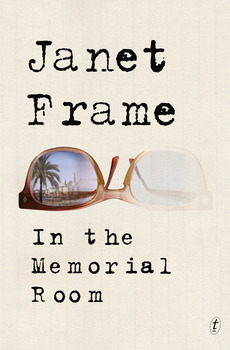

In the Memorial Room is both literally and figuratively posthumous. It centres around themes of creativity, being a writer, and a writer’s posthumous memorialisation. Frame wrote the novel in 1973, but did not allow its publication during her lifetime. The preface offers one possible explanation: ‘would certain people see themselves in the characters portrayed and, finding unflattering portraits, be offended?’ For these or other reasons, Frame ‘always intended the novel to be published posthumously’.

Another of Frame’s novels, Towards Another Summer, which appeared in 2007, was similarly conceived as a posthumous work. Its protagonist, Grace Cleave, is a New Zealand-born writer in her early thirties who is living in London. She is an acutely sensitive introvert whose once-golden hair has faded to dust. When she is asked a question about returning to New Zealand, she responds: ‘I was a certified lunatic in New Zealand. Go back? I was advised to sell hats for my salvation.’

The shards of her childhood memories of loss and play echo events depicted in Frame’s autobiography, and her remembered prescription of hat-selling recalls an episode in An Angel at My Table, in which a nurse, promising a swift return to ‘normal’ should Frame undergo the leucotomy, describes another patient’s success:

We had one patient who was here for years until she had a leucotomy. And now she’s selling hats in a hat shop. I saw her just the other day, selling hats, as normal as anyone. Wouldn’t you like to be normal?

This invitation – and Frame’s edgy satire – is reminiscent of the doctors who treat Septimus Warren Smith in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925), one of whom suggests cricket as a remedy for the post-traumatic symptoms of what would then have been called shell-shock: ‘the very game … a nice out-of-door game.’ As in Frame’s work, the fictional moment has its origins in the author’s insensitive treatment by medical professionals. Leonard Woolf recalls one doctor, consulted about his wife’s shifts in mood and elevated temperature, advising her to ‘practice equanimity’. He might as well have said, Leonard Woolf wrote, ‘practice a normal temperature, Mrs Woolf, ninety-eight point four.’

Such anxious promotion of ‘normality’ persists, of course, but arguably with nothing like the stigma these writers experienced, and within a context where psychiatry has become a more enlightened profession. For Frame, the experience of stigmatisation was associated with her literary aspirations. ‘Everyone felt that it was better for me to be “normal” and not have fancy intellectual notions about being a writer,’ she writes in her autobiography. Yet she was always clear that she wanted to be a writer. Even as a child, she understood the conflict involved in knowing she was a writer in a society where this was odd, especially for a girl: ‘They think I’m going to be a schoolteacher, but I’m going to be a poet.’ Among the magnificent images in Jane Campion’s film of An Angel at My Table is a close-up of Frame (Kerry Fox), watched by children – some feckless, some deeply sympathetic – and a school inspector, as she realises she is simply unable to continue teaching. The moment brilliantly recreates Frame’s own description. And after her stay of execution, there would be no dissembling.

Grace Cleave, in Towards Another Summer, is similarly caught between social mores and the call of her imaginative world. Like her fictional namesake, John Banville’s Alexander Cleave, she is as ambivalent as her name suggests: she is both clinging to and breaking from her past. She is a writer, sometimes called a poetess, a word that is ‘sprayed like a weedkiller about the person and work of a woman who writes poetry’.

Towards Another Summer describes Grace’s weekend visit to the home of journalist Philip Thirkettle and his New Zealand-born wife Anne. A whimsical, exquisite work, it moves between the social comedy of Grace’s attempts to engage socially and a tender anatomising of the introverted artist. The weekend galvanises Grace, and the novel dramatises her decision to give up pretending to be other than she is. She decides to return first to London, then to New Zealand, to live truthfully and to write the truth about her life.

In An Angel at My Table, Frame elaborates on her own similar decision:

although I have used, invented, mixed, remodelled, changed, added, subtracted from all experiences I have never written directly of my own life and feelings. Undoubtedly I have mixed myself with other characters who themselves are a product of known and unknown, real and imagined; I have created ‘selves’; but I have never written of ‘me’.

For Frame herself, after a similar weekend visit to the writer Geoffrey Moorehouse, something else, arguably, served as a powerful confirmation of these choices.

*

An Angel @ My Blog is a carefully curated website maintained by Frame’s literary estate. A 2008 post describes Frame’s arrival back in London on Sunday February 10, 1963, after her weekend with the Moorehouse family. The next morning, in another London flat, Sylvia Plath committed suicide. Frame told friends that when she heard the news of Plath’s death, she left her flat and spent the day on a London bus, grieving. On 14 February, she began the novel that would become Towards Another Summer. Later in 1963, she would begin her autobiographical trilogy and return to New Zealand.

Towards Another Summer includes a poem with the lines:

I rode on a red bus

inside a clot of blood

I rode in grief over London,

I smashed nothing, no mirrors, windows, or glass sheets of sky.

I prayed Let the world have wonder enough to care

when poets live

and to grieve when they die.

In its blood, glass, red and (withheld) smashing, it is almost as though Frame, via Grace, ventriloquises Plath. There is a sense at the end of Towards Another Summer of a fate averted, and another faced. The glass is not smashed.

In Plath’s ‘Contusion’,

The heart shuts,

The sea slides back,

The mirrors are sheeted.

Instead of the aversion suggested by Plath’s imagined shiva mirrors, Frame chooses to face the mirror. She calls the third volume of her autobiography The Envoy From Mirror City (1984) and a volume of poetry The Pocket Mirror (1967), and mirrors recur as symbols throughout her work. When a man is imagined to have swallowed one in Towards Another Summer, Grace imagines a knee-jerk response of ‘Freud, Freud’, which she likens to squeezing an old sponge.

Towards Another Summer and In the Memorial Room are both posthumous in the sense that they follow Frame’s escape from misdiagnosis and leucotomy. They express the sense of inheritance captured in Grace’s poem. The poignancy of Frame’s response to Plath’s death suggests her understanding of the conditions that made Plath’s life impossible, and a kind of responsibility or a sense of relief that she had escaped a fate that could well have been hers.

In her review of Towards Another Summer for the Canberra Times, Marion Halligan uses the first person plural to describes Frame’s writerly sympathy with Grace’s plight and her return to the desk in London:

This is the writer naked, skinned, raw. We feel for her in her vulnerability. We are grateful that she has got back to her desk in its corner by the bookshelves, the lamp, the piles of paper, the typewriter.

Of the return of Grace to her writing, Halligan writes: ‘This is where the migratory bird belongs.’ One of the reasons Grace feels that she ‘needed courage to go among people, even for five or ten minutes’ is that she believes she is a migratory bird. (In Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, a network of sensitive characters centred on Clarissa Dalloway is connected by similar bird-like traits.) She takes comfort in the fact that her belief means she does not need to judge herself as a human being: ‘if I were human and not, now, thankfully, a migratory bird, I should be one of the first programmed human machines, my cold eyes flashing their lights at stated intervals, and my mouth emitting its cardboard code.’ Her diagnosis provides a kind of cover. Frame’s diagnosis of schizophrenia perhaps served her in the same way. When it was taken away, she felt oddly bereft – without an explanation for her difference.

*

Harry Gill, protagonist of In the Memorial Room, is like Grace Cleave in many ways. If she is a migratory bird, he is the landed fish. This ‘shy little mild man’ who sees himself as a fool and a doormat, recalls J. Alfred Prufrock, or J.M. Coetzee’s fictional John Coetzee in Summertime (2009). An unassuming writer in his early thirties, Harry has won a Fellowship that brings him to Menton and the Memorial Room, named in honour of the fictional poet Margaret Rose Hurndell. His self-portrait, like Grace’s and Frame’s, is harsh. He hopes to write a picaresque novel despite – or because of – a lack of picaresque qualities in himself: ‘I am a dull personality, almost humdrum,’ he observes, noting that the salient features of this condition include a plodding voice. He is ‘shy, bespectacled, rather slow on the uptake’. He finds himself ‘questioned in a conformist society’. He conserves what libido he has ‘for the purpose of staying alive’.

Harry repeatedly reminds himself that ‘my story is of the Tenure’. Frame wrote In the Memorial Room during her own tenure as Fellow in the Katherine Mansfield Memorial Room at the Villa Isola Bella in Menton, France, in 1973. Conditions in the room itself were basic, as are those in Harry’s room. He describes it as ‘another grave for [the poet]’ and exclaims: ‘A unique memorial, to pay a writer to work within a tomb!’ The memorial display exemplifies Frame’s wry wit. It includes a handkerchief and a copy of a certificate won by Hurndell at primary school for the best long jump.

Harry finds that he cannot work there. When he visits the room, tourists ‘curious to inspect the open tomb’ interrupt his thoughts. When one of the rapturous and fatuous guardians of the Fellowship and legacy asks about his visit to the room ‘Did you feel Rose Hurndell there?’, Harry suppresses an irreverent, ‘lustful thought’.

Frame’s delicious satire here is reminiscent of Jane Austen. Her two posthumous novels highlight this subtle and hilarious streak in her writing – which was there from the start, despite the dark subject matter of her earlier work. A long section of her first novel, Owls Do Cry (1957), satirises the conventional aspirations of the protagonist’s sister, though it sits oddly and is overshadowed by the brilliant linguistic play in the other sections. In these journal entries, the young woman works hard to conform, to be ‘normal’ and move higher socially, partly in response to the experiences of her sister, ‘Daphne of the Dead Room’, who has been institutionalised for mental illness.

In Menton, would-be writers and the keepers of the memorial pester Harry. Connie and Max Watercress and their adult son Michael are among the most persistent. Although Connie and Max preface their praise of their son’s talent with the aside ‘He’s not written a book yet’, Michael looks as Harry thinks a writer should, and his great self-confidence reinforces the image. When a photograph of Harry is to be taken, the handsome, bearded Michael is mistaken as the Fellow. Harry shuffles at the side of the frame, shy and unphotogenic: ‘a rather stocky young man with glasses and curly hair and a look of what might be frenzied embarrassment on his face.’ Michael, on the other hand, is characterised by lines that run through Harry’s head:

– Such a clever boy.

– He has perfect pitch.

– Perfect pitch.

– He could be anything.

Frame’s humour operates like a trip-wire, only occasionally overt, but always creating a tension in the narrative. Michael is the overpraised offspring whose story of himself precedes – and, Frame seems to suggest, generates – success:

Michael was the genius, the writer – well, the talented young man who could be (it was not yet the time in his life when one said ‘could have been’) a writer, or painter (he’s always been good at drawing and painting) or a composer and musician (he has perfect pitch, he nearly took a music degree, he has composed hundreds of songs and pieces of music’).

Someone compares Michael with the young Hemingway, and Harry realises he will ‘never be called the young Hemingway. I didn’t even look like the young Hemingway.’ His self-image is so uncertain, he is so lacking in confidence, that he begins to suspect that Michael may well be the real Fellow. But Frame also suggests that alongside polished young Hemingways, a real writer may always be awkward.

No one at Menton does much reading, though they perform what Harry thinks of as a ‘pseudo-reading’, which consists of rushing about making comments to the effect of having ‘heard of’ writers’ work – including Harry’s. The most positive thing they have to say about this is that there is ‘a shortage of historical novelists in New Zealand … as if talking of petrol or transistor radios or vacuum cleaners.’

Frame offers several other dark comic portraits of characters beset with doubts about language and society. George Lee, husband of the Head of the Welcoming Committee, has such an ‘astonishingly unintelligible English voice’ that all his remarks sound like the one sentence: ‘Angela will be livid.’ This surface absurdity allows Harry to interact conversationally better with George than with most others:

He: Angela will be livid.

I: Yes, I was there last week.Or thus:

He: Angela will be livid. Angela will be livid. Angela will be livid.

I: I found it quite pleasant in its way, considering.

Harry’s assessment of George’s speech projects his own anxieties. He describes him as ‘one who “spoke with tongues” concealed amid the dreadful exposures of clear enunciation which were enacted around him.’ Another man, a retired scholar of languages, gives himself the task of speaking only in nouns and verbs. This leads Harry to imagine a version of himself at once deeply in sympathy with this decision to abjure language, yet the idea is expressed in a subversive flurry of modifiers. He sees this vision of himself ‘unadjectived, unadverbed, fully nouned and verbed’. Concealment and disclosure again wrestle in the subtext.

Where Grace Cleave feels the shiver of budding feathers under her skin, Harry Gill is convinced he is losing his eyesight. The doctor he visits, Dr Rumor, is the antithesis of George Lee: he speaks English ‘to such perfection that I became convinced my own English was “broken” and foreign.’ Harry finds himself adopting ‘the formal English of the foreign student who learns from Cambridge University entrance papers of fifty years ago.’

Rumor diagnoses ‘intentional invisibility’. The pantomime and sham of Harry’s imposed social life continue around him nevertheless, as he (like Grace) grapples with the impossible script of social chit-chat. The ‘chuckling birds’ are the only ones who seem to know anything. Romanticisation of writers is, Harry decides, like sheltering from ‘the blizzard by creeping within the bloated hollows of the dead horses’, an idea he adapts from an image in a Victor Hugo story He regains his composure, until one day he awakens deaf. Dr Rumor calmly explains this as an extension of his intentional invisibility: a ‘sealing-off, a closure. Auditory hibernation.’ Like his aunt with Meniérè’s Disease, Harry has been ‘stifled, muffled, silenced. You cannot cry out because you cannot hear the cries of others.’

‘But we’ve never had a deaf Fellow!’ ‘Angela will be livid.’ ‘Clever boy. Perfect pitch.’ ‘Angela will be livid.’ In the face of others’ reactions, Harry insists (writing on the pages he carries with him) that nothing has changed. Yet the effects on Harry’s manuscript are evident. When Harry speaks now, he shouts, and his writing is similarly augmented.

Tumbling across the page from this point in the novel is a hilarious, spiralling and brilliant interior monologue, a bizarre implosion jewelled with the stifling clichés that have caused Harry to deafen. Wild and mischievous, it is part Molly Bloom, part hat-salesman, part-psalm. From the novel’s quiet, observant narrative bursts forth a vibrant new language of the secret, shouting Harry, like the ‘mutinous lunacy’ he has observed earlier: a bright mosaic tessellated with all the smooth phrases he has endured: ‘It is with deepest sympathy … Please accept our … Congratulations on your birthday … I have heard a rumour of your sad news. Many people have gone through this experience. Many people recover. Your own courage and cheerfulness are your best medicine …’

‘It amused me,’ Harry thinks, ‘to suppose what the last word would be.’ And this, in the end, is Frame’s last word – brilliant, original and wry – on fiction, the posthumous writer, and the whole business of being the dead horse in which a pseudo-literary culture cowers, to shelter from shocks.

References

Michael King, Wrestling with the Angel: A Life of Janet Frame (Picador, 2000).

Elizabeth Schulte, ‘The Trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg,’ International Socialist Review, issue 29 (May-June 2003).