Two lives. Two books. The lives of two women, two artists, told by two novelists.

Two women, both of whom died too young.

Correction.

One died due to medical advice that kept her in bed for eighteen days after the birth of her daughter. On the day she was allowed up, she asked for a mirror, plaited her hair, stepped out of bed and fell to the floor. Paula Modersohn-Becker, dead of a pulmonary embolism. It was 20 November 1907, and she was 31. A shocking, needless death ‘as women used to die’, an ‘old-fashioned death’ that Rilke memorialised in ‘Requiem to a Friend’.

…you who have achieved

more transformations than any other woman.

Paula Modersohn-Becker who just the year before, in 1906, had painted a run of self-portraits that would usher in a century of women’s modernist self-expression. Your stern death broke in upon us, darkly.

For Charlotte Salomon, death is too kind a word. She was murdered at Auschwitz on 10 October 1943. She was 26, and five months pregnant.

In the two years before she was deported, Charlotte Salomon had painted close to a thousand gouaches accompanied by sheets of tracing paper on which she’d written dialogue, narrative and musical notations. From these she assembled Leben? oder Theater?. Subtitled Ein Singespiel, an operetta, or play with music, Life? or Theatre? is variously described as ‘a play in art’ or a ‘virtuoso graphic novel’. That this extraordinary, hard-to-classify work survived is due to the doctor to whom she entrusted it. ‘This is my life’, she told Dr Moridis. Life? or Theatre? is now in the collection of the Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam, and was exhibited in its entirety for the first time in 2017. An English edition of the complete work was also published in 2017 in a magnificent – and magnificently expensive – edition by Duckworth.

Two lives. Two deaths. Two artists, both German, brought to popular notice by French novelists. Both are well served by their English translators.

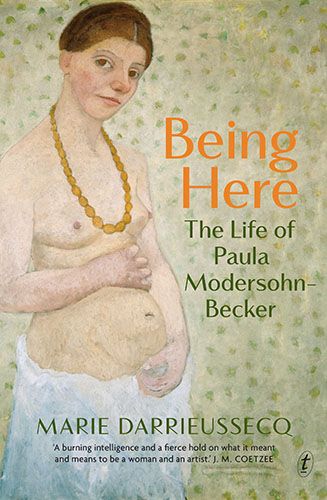

Marie Darrieussecq’s Being Here: The Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker begins at her grave in the small town of Worpswede in northern Germany. The grave, Darrieussecq writes, is horrible. It is certainly large, a brick and granite memorial topped by a half-naked reclining woman, larger than life, a naked baby sitting on her belly. Darrieussecq was there in 2014, and found the town pickled in tourism. Fifteen years earlier, when I visited, I quite liked the weather-beaten extravagance of the grave and could forgive a lot simply because it was designed by the sculptor Bernard Hoetger, one of the few who understood her turn to Expressionism – the ‘modern’ that had dismayed her family – and told her so when she was alive to hear it. ‘Now I have courage,’ she wrote after his visit to her Paris studio in 1906. ‘My courage was always behind barricades…’

Hoetger was making a large statement with that grave. He made another when commissioned to design a museum in her name to house the collection of over 400 paintings and more than 800 sketches and drawings that were in her studio when she died. Among them, now on permanent display, was her great Self-portrait on the 6th Wedding Day. It too is large and monumental, but subtle and beautiful. She stands there, life-sized, with a white cloth wrapped around her beneath the pregnant belly she holds, an amber necklace between breasts that are small and pointy, not swollen with pregnancy. The first woman to paint a nude self-portrait, she shows herself pregnant when she was not. We are creative beings, the painting says; doubly creative. The question that hovers over the painting, and over Paula Modersohn-Becker’s life is: how does a woman live that doubled fecundity?

Foenkinos’s Charlotte begins at the grave of Charlotte Salomon’s aunt, her mother’s sister after whom she was named. Charlotte knew this aunt only as a name on a grave, and it wasn’t until 1940 that her maternal grandfather told her not only that this first Charlotte had committed suicide, but that her own mother had died not of influenza as she’d been told, but by throwing herself from a window. Charlotte, her grandfather told her, was the last surviving female in a family of suicides. This terrible revelation was made as her grandmother too threw herself from a window in Nice where they were living in exile from Berlin. It was May 1940, the month Germany invaded France, and Italy declared war.

‘I have a feeling the whole world has to be put together again,’ the Charlotte figure says to her grandfather in the penultimate painted image of Life? or Theatre? To which he replies: ‘Oh go ahead and kill yourself, and put an end to all this.’I think

Instead of suicide, the taunt, the temptation, to end it all, Charlotte Salomon began the work that would, in the short space of eighteen months, become Life? or Theatre?

For Jacqueline Rose, Life? or Theatre? is Charlotte Salomon’s refusal of death. ‘Her cry for freedom.’

Both Darrieussecq and Foenkinos write with personal intensity, moved, angered, impassioned by the lives of the women they bring to the page. Both follow in the footsteps of their subjects. Darrieussecq travelled to Worpswede several times, looking at the paintings, talking to curators, visiting the grave, and the house with red ropes to keep you from rooms that once breathed with Paula Modersohn-Becker. Foenkinos is rebuffed at the door of the flat in Charlottenburg where Charlotte lived with her father and stepmother until she was sent to join her grandparents on the Côte d’Azur. He stands outside the villa in Villefranche where she was given refuge, and looks out across the blue of the Mediterranean.

Yet they both resist the protocols of biography. Darrieussecq offers few footnotes, and though she lists her sources and indicates every line taken from them, they are not easily followed unless you know them. She is, she says, writing not Paula M. Becker’s life as she lived it, but my sense of it a century later. A trace. Although Foenkinos’ novel is ‘inspired’ by the life of Charlotte Salomon, and his ‘principal source’ is Life? or Theatre? it is rarely clear where he takes lines from it, and where he invents, or elaborates.

Significantly, neither includes illustrations or plates. The Text edition of Being Here has Self-portrait on the 6th Wedding Day as its cover image. The cover of the Canongate edition of Charlotte does not use the self-portrait that is on the cover of US editions. Both Darrieussecq and Foenkinos rely on the power of narrative to bring us the lives of these two women, and the remarkable art without which there would be no story to tell.

Anyway, Darrieussecq asks, how do you write paintings?

It is a key question in the success, or failure, of these two books.

Worpswede, where Paula Modersohn-Becker’s story ends at that grave in the churchyard, is fifteen miles to the northeast of Bremen. An artists’ colony had been set up there in 1889, and for the young Paula Becker growing up in Bremen, it was ideal, a route to the life of art her parents considered foolishly impossible. It was only when one of the colony’s founders offered her a place in his class that she was finally allowed to go.

In Fritz Mackensen’s class she met the young sculptor Clara Westhoff, who would become one of the most significant figures in her short life. It was a glorious meeting – see them speeding home on a sled from their classes – and not just in Darrieussecq’s telling. There’s a photo of them around that time, both in high-necked blouses, turned to each other, unaware of the camera. Clara became a star in her constellation. The artist Heinrich Vogeler, who believed in the bonds of community and art, invited them to evening salons at his house where he played guitar and read poetry; the tables were pushed back for dancing. It was there that Paula met the landscape artist Otto Modersohn. His wife Hélene was perilously ill – she would die of tuberculosis in June 1900 – but still he was there, too soon in Vogeler’s view, talking to Paula of books and art. She knows her new green velvet dress suits her perfectly.

As with every account I’ve read of Paula Modersohn-Becker’s life, we see the two girls out walking one respectable Sunday, wanting to dance. But where and how? A brainwave. They climb up to the bell-tower, grab hold of the ropes and ring the bells. What a scandal. The schoolteacher comes rushing out …. The vicar, out of breath, hisses ‘Sacrosanctum!’ A small crowd gathers. The people who owned Paula’s studio defuse it. ‘Fräulein Westhoff and Fräuline Becker? Impossible! They were in Bremen.’

It was the summer of 1900, roses everywhere, a perfect prelude to the arrival in Worpswede of Rainer Maria Rilke. Paula and Clara had been in Paris for six months; their confidence and their knowledge of art had taken a step forward. Clara had studied with Rodin, Paula at the Academy Colarossi. They’d spent hours at the Louvre, and came across their first Cézannes at Vollard’s gallery where, a year later, the young Picasso would make the same discovery. Back in Worpswede, they were ripe for more as Rilke arrived from Russia to visit his friend Heinrich Vogeler. It was at Vogeler’s house with wide veranda and sweeping steps that the poet met the two young women.

First Paula in her green dress. ‘The reddest roses never showed so red.’

Then Clara, wearing a white dress. ‘The slender birch trunks never stood so white.’

They talked of poetry, of sensation, of love, of the colour of the marshes. Rilke stayed on to see the seasons. Or the two young women. Rainer Maria Rilke is in two minds. Paula, Clara. His heart is torn. He has a preference for threesomes, which will continue his whole life.

Thousands of words have been written about this three-way meeting, not least by Rilke himself, and Darrieussecq is at her best as she weaves a path through them to give us her trace of that rose-scented summer. Her words, her use of the historic present interspersed with words written at the time, are like brushstrokes. Clara rides on the bicycle, breathless. Paula waves. ‘The lissom Clara, like a radiant green reed’. Paula paints the walls of her studio turquoise and blue. ‘Her voice had folds like silk.’ Rilke is a stem popped out of a bouquet.

All three are in love – with each other, with love, with the profound. It was enough to send Rilke running over the moorlands.

He is gripped by something bigger than him – the sky, beauty. He plummets towards the summit.

He does. They all do.

And don’t forget Otto Modersohn, he is there somewhere. Stolidly there, always there. A godsend of a man whom Paula Becker wants to shield with her hands. In September, four months after Hélene’s death, she agrees to marry him. She makes the sensible choice and writes to tell Rilke who has left for Berlin as suddenly as he arrived. He is hurt. Paula and Clara will both see him in Berlin. He proposes to Clara. Paula is hurt. Clara retreats. She has to; she has taken the dangerous man. Once married, she will retreat further, bending to do his will, Paula writes, ‘like a floor cloth on which her king can tread’. Their friendship took several years to recover. The friendship, if that’s what it was, between Paula and Rilke remained ambivalent, intense, unreliable, profound.

The two weddings took place in the spring of 1901.

Both marriages would prove a disaster.

Clara and Rilke had a child, Ruth, within the year, and Rilke found it impossible to write with a baby crying. He left for Paris, and soon after Clara entrusted the child to her mother so she could join him. To and fro, for a few years. He was evasive, unreliable, broke and adamant that the needs of Art must take precedence over the daily cares of Life. Even without the child, in Paris Clara must live separately. When she returned to Germany, Ruth did not recognise her.

For Paula marriage was profound only in its disappointment. Later she’d confide to Clara that Otto could not consummate the marriage. Rather than the ‘wonder and excitement’ she’d expected on ‘becoming a woman’, she discovered the lonely truth that ‘marriage does not make one happier. It takes away the illusion.’ She was left ‘doubly misunderstood.’ The summer of lightness and flowers was replaced by long dark months of winter as Paula also came to understand just how conservative an artist Otto was. In 1901 he’d sketched her out in the landscape with her easel. By 1903 she’d retreated to her studio, experimenting with portraiture, flattened expressive figures of local girls and women. Twice she persuaded Otto to let her go to Paris, and each time she moved further from him. Out in the weather Otto stood doggedly at his easel while she read Gauguin’s Tahitian journal. Her portraits of local girls became simplified as she abandoned perspective, bringing them forward onto the picture plane.

Otto was not pleased. ‘She admires primitive pictures, which is very bad for her. She should be looking at artistic paintings…. Women will not easily achieve anything proper.’

1905. The year Paula and Clara were reconciled. Paula painted the portrait of Clara that is now in Hamburg’s Kunsthalle. While Ruth played on the floor between them, Paula painted her sombre, her knowing eyes averted from us; no trace of illusion. It is a magisterial painting, substantial, in few colours, with roughened edges and an unadorned background.

1905 was also the year she painted Self-portrait with Irises. A small painting, greens and blue for irises, rendered not as Otto would like them, but an expressionist hint, part of the background against which Paula steps forward, a black necklace at her throat, dark eyes, unflinching. It is a tipping point. Pure simplicity: this is me, these are the irises. See: this is what I am, in colours and in two dimensions…

By the end of that year she could no longer endure Worpswede, or Otto. We know, as Paula did not, that time was short. It is a tension that Darrieussecq uses well. She doesn’t sentimentalise; the sadness and loss is alive in the interweaving of Paula’s words as she leans to the future, pushes forward her art, experimenting, resisting both Otto’s conservatism and Rilke’s dictum that Art trumps Life, finding ways to express that being here.

During the tipping-point year of 1905, Paula saved a little money and with Clara’s help, early in 1906 made her escape to Paris. Rilke was there, a combatant and a lure, support and complication. Were they ever lovers? Darrieussecq thinks not; maybe; does it matter? There was an entanglement: a doubled triangulation. Clara. Otto. And that dance, repeated in the life of many a creative woman, of attraction and retreat: the dangerous, alluring man; the safe but boring man.

In Worpswede, Otto was frantic. ‘Let me go, Otto. I do not want you as a husband.’ But even as she wrote these letters she had to ask for money. His landscapes sold. She was painting behind barricades. That year in Paris – when Hoetger visited her studio – she painted more that eighty canvases: still-lifes, women and babies, self-portraits, large nudes. And then the nude self-portraits, including Self-Portrait on the 6th Wedding Day. Life-sized, with a radiant background, greens and yellows that do not reproduce well, she nurses a pregnant belly. No, she’d written to Otto, a child is no longer possible.

Paula Modersohn-Becker experts, all thirty of them, have puzzled over this painting. Did it mean she did want a baby? Or that she didn’t? Could her diet account for the shape of her belly? Darrieussecq comes down on the side of a desire – that would be fulfilled, if that’s what it was, when Otto came to her in Paris at the end of 1906, and a few months later she returned with him to Worpswede.

Their daughter Mathilde was born on 2 November 1907. Paula died of that pulmonary embolism on 20 November.

As she collapses, she says, ‘Schade.’ Her last word. A pity.

Reading Being Here sent me back to the sources: to Paula’s correspondence and journals, to Rilke’s letters and diaries, to the existing studies of these key players. (Little that’s been written about Clara Westhoff is translated into English.) The more I read, the more I admired Darrieussecq’s trace, this little biography. It’s no easy task to render a sprawling archive into a narrative that captures the significance of Paula Modersohn-Becker for a readership a century later – a figure not only of her time but also for ours. A trace, she calls it, and yes, it is her trace and with it she achieves – more than existing studies have – the aim Hermione Lee posits for all forms of biographical and life-writing: ‘a living person in a body, not a smoothed-over figure’.

Darrieussecq puts her own aim, her hope, this way: I want to do her more than justice. I want to bring her Being There, splendour. And so the French edition was published in 2016 alongside a retrospective of Modersohn-Becker’s work that she co-curated at the Musée d’Art Modern de la Ville de Paris. A spring and summer for Paula. For while she was well known in Germany, when Darrieussecq began this task, across the border in France, she was barely known at all.

In writing about Modersohn-Becker, Darrieussecq had two advantages. Firstly her biography is largely uncontested. The inflection put on it has shifted dramatically with twentieth-century feminist readings, but the events of her life, the broad line of her relationships and influences are largely agreed. While letters are composed, a form of performance – especially in Rilke’s case – they are of the moment, written without knowing what is to come. As contemporaneous sources, letters and diaries (in their unedited form) are, so to speak, reliably unreliable. The shifts and tensions between Paula, Clara and Rilke, and between Paula and Otto, played out in their letters, their contending views on art and life, are a gift to any writer.

The second advantage is that Modersohn-Becker’s oeuvre is comprised of individual paintings, many of them portraits and self-portraits, and her expressionist style is able to be given some equivalence in the prose of a writer of Darrieussecq’s calibre: those brush-stroke quotations bending us towards Paula in her effortless use of a free indirect style. And in the absence of images within the text (which can be prohibitive in terms of permission and printing costs), if needed, the major works come up immediately on Google.

Foenkinos has neither of these advantages. Life? or Theatre? is a huge and complex work. ‘An unprecedented and unclassifiable project,’ Griselda Pollock calls it. ‘A monumental modernist artwork.’ There is no way to see Life? or Theatre? as a single work, other than to see it in its entirely. With 871 images, overlays and painted texts, even Google fails. There is no easy way, perhaps no way at all, to give its complexity equivalence in another layer of words. Some of the images delve inwards, many spiral outwards into multiples; many are allusive, fragments, notations, dreams; some layered, almost architectural; some could be from a story-board for a film; others are philosophical; some composed solely of words. All the figures in Salomon’s life, including herself, become characters, as befits an operetta; each is given a name that is similar – coded, a reference – but not the same. ‘I learned to travel all their paths, and became all of them,’ she wrote in the postscript. While Charlotte Salomon revisits her own experience through the avatar of Charlotte Kann, Life? or Theatre? cannot be considered contemporaneous. Created under the extreme pressure of war and her grandfather’s revelations, it is a great deal more than the ‘autobiographical work’ Foenkinos calls his ‘principal source’.

Like Darrieussecq, he uses the historic present, and with each sentence starting on a new line, he builds tension into a highly readable narrative. This urgency of style is complemented by his first-person presence as he searches for Charlotte Salomon, walking her streets, speaking to people who remember her. The combination of style, its pace, and the emotion of his search for traces of her, does not let us forget that while this might be a novel – with the leeway that implies – it is also the ‘life’ of a once-living woman, an artist whose name was known by only a few in 2014, when Charlotte was first published in France.

He begins the novel at the grave of Charlotte’s aunt, her mother’s sister, Charlotte Grunwald, who threw herself into a lake four years before Charlotte was born. Charlotte’s mother Franziska married Albert Salomon, a surgeon she met while nursing during the first world war. The haut-bourgeois Jewish Grunwald parents were not sure that Albert, with no family wealth, was a suitable husband, but the marriage was allowed, and Charlotte was born in 1917. When she was eight, her mother suffered a depressive episode during which she was sent to stay with her Grunwald parents. It was there that she threw herself from a fourth-storey window. Influenza, Charlotte was told. With her father by then also a professor at the university, she was given into the care of nannies until remarried in 1930. The thirteen-year-old Charlotte was enchanted by her stepmother, the contralto Paula Lindberg – and by the theatre, and the music, and the musicians who came to their apartment in Charlottenburg.

She was sixteen when the Nazis came to power in 1933. She already knew the jab of anti-Semitism, of course, but had accepted her father’s rationalisation, sufficiently protected from it – until the evening at a performance by Lindberg, when the booing began, a voice here, another there, until the theatre rang with hatred. It was not just a few fanatics. It was everywhere. It was at school. And it was at the Berlin school for Fine and Applied Arts – she was the last Jewish student accepted – where she won a blind arts competition and was denied the prize when the judges realised it was her.

Albert Salomon kept working while Charlotte and her stepmother retreated indoors. In Charlotte, they cease to understand each other, an estrangement made worse by the presence of Alfred Wolfsohn, a voice coach who was frequently at the apartment. Introduced to Lindberg by Kurt Singer, who’d founded the Kulturbund in an attempt to safeguard Jewish cultural workers, she took him on as a favour. Wolfsohn had been wounded in the first world war, a trauma from which he developed a therapeutic method of recovery using the allegory of the Orpheus myth: the re-enactment through song and music of a descent into the dark, into ‘death’, as a prelude to a return, or rebirth, into light, and life. The Orphic journey with its Freudian and undertones becomes the core of Life? or Theatre?.

Twenty years older than Charlotte, Wolfsohn saw her drawings, recognised her talent, encouraging her to keep painting – and she fell in love with him. In Charlotte Wolfsohn is besotted with Paula, yet he and Charlotte have a number of impulsive, sexual encounters, leaving her in a state of unrequited longing. She stayed in Berlin, refusing to join her grandparents on the Côte d’Azur until after Kristallnacht and the shock of her father’s arrest and detention. When Lindberg managed to get him released from Sachsenhausen, Charlotte reluctantly boarded the train to France. It was December 1938.

Her grandparents had been offered sanctuary by the American Ottilie Moore and were living at her estate at Villefranche, near Nice. The beauty of the place, pepper trees and the blue of the Mediterranean, was clouded not only by the war that began in September 1939, but by the demanding, imperious behaviour of her grandfather Ludwig Grunwald. Early in 1940, he insisted the three of them leave Villefranche, at odds with Ottilie Moore as she brought in more children for refuge. It was in Nice that her grandmother committed suicide, and her grandfather gave Charlotte the blunt history of family suicides. This time Charlotte, who’d spent nights singing life into her grandmother, saw the bleeding body beneath the window.

First this private horror, and then the closing in of war as Germany invaded France, and Italy declared war. All German citizens were ordered to declare themselves, and in June Charlotte and her grandfather were on a train to the internment camp at Gurs. Whether they reached the camp is one of the unverified events of Salomon’s biography. Either way, it was a further descent into the dark. The camp at Gurs was grim, crowded and dehumanising; Hannah Arendt who escaped over the border to Spain in September, later wrote that she contemplated suicide there. Foenkinos has Charlotte at Gurs, as do most of those who’ve researched her life, including Griselda Pollock in her exhaustive 500-page study, Charlotte Salomon and the Theatre of Memory (Yale 2018). But, assuming she was there, Foenkinos doesn’t question – or even mention – the absence of Gurs from Life? or Theatre? Was it, as Pollock suggests, a ‘traumatic gap’ that initiated and underpinned the ferocious ‘operetta’ that she began within months of her return to Nice. In Charlotte Salomon’s own rendition of her life, it was on the long trek back to Nice that grosspapa becomes increasingly monstrous, insisting that Charlotte share his bed. ‘I’m in favour of what’s natural,’ she has his character say in Life? or Theatre?. Charlotte Kann would rather ten exhausted nights in a crowded train than ‘a single one alone with him.’

Was she, too doomed to death, and by death?

Could song, could art, transcend the dark of this doubled despair?

The answer, this time, was Yes.

Encouraged by Dr Moridis, ‘this strangely twin-natured creature’ – as Charlotte Kann calls herself – left her grandfather and returned to Villefranche. Ottilie Moore found her paper and paint of three primary colours, red, yellow and blue. And so Charlotte Salomon delved into herself, into the darkest depths, plunging into memory: her love for Wolfsohn, his singing cure; the conversations around the table in Charlottenburg; all the reading she had done; the art she’d seen; all of it, and film, and theatre. She gathered everything in, and the characters from her family, and the swastikas, to create the ‘monumental modernist masterpiece’ that was shown in its entirety for the first time last year.

After the war, Albert and Paula – who’d survived, in Holland – were given the two wrapped packages of Life? or Theatre? In 1971 they gave it to the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam. Albert Salomon died in 1976, and Paula Lindberg maintained tight control over when, how, and how much could be seen – and by whom. She insisted that the affair with Wolfsohn – to whom Charlotte Salomon gave the name Amadeus Daberlohn – couldn’t have happened, and she held back the incriminating pages. Yet Foenkinos plays the affair for all its narrative potential, preparing us for it by giving the teenage Charlotte a fascination with breasts – her nanny’s, Paula’s, her own. It is an easy novelistic move, an insertion entirely his own. My objection is not for prurient reasons, nor to question the affair – whether or not they were lovers is not the point – but because the hundreds of drawings of Daberlohn/Wolfsohn, indeed obsessive and eroticised, carry the intellectual heft of this extraordinary work. It is through his voice, his singing voice, his obsessive voice, and Charlotte Kann’s obsessive and eroticised response to this ‘prophet of song’ that the philosophical and moral weight of the work is refracted. That is why ‘the affair’ matters, not as an unrequited love story – which it may well have been – but as the core of her Orphic journey.

Life? or Theatre? The title is a serious question, not easily answered.

Charlotte gave Dr Moridis the precious packages early in 1943. When Albert and Paula opened them, along with the gouaches and overlays, was a post-script on poorer quality paper: thirty pages of painted script. When Life? or Theatre? went into the Jewish Historical Museum in 1971, seven of those pages had been removed. Fortunately – for us, for history – in the mid-1970s, the filmmaker Frans Weisz and scriptwriter Judith Herzberg saw those seven pages and transcribed them. The full post-script – translated into English in 2002 – was made public in 2012. It is included in the 2017 Duckworth edition of the complete work.

The post-script is a letter from ‘Charlotte’, written in the first person – unlike the third person of Life? or Theatre?. Using the informal du, it is addressed to Doberohn, not to Wolfsohn. In it she tells him about the months between finishing the work and giving it to Dr Moridis. It was a descent – again – from ‘brilliant sunlight’ back to ‘grey darkness’. She’d had to return to Nice to look after her grandfather; news of the deportations of Jews to Poland had reached them; Ottilie Moore had returned to America. As if released from the theatre of respectability, the last shreds of human kindness vanished; her grandfather’s cruelty, his threats and insults, his assaults on her very being, led to her realisation that he ‘was the thorn of the diseased state’ inside her. And she tells Doberohn/Wolfsohn of her relationship with Alexander Nagler, a one-time lover of Ottilie Moore, who’d stayed on at Villefranche; not a love like hers for him, but a small comfort.

In those seven redacted pages, Charlotte makes a ‘confession’ that puts another large, unsettling question mark into the theatre, and life of Charlotte Salomon. It took ‘a great deal of strength,’ she wrote, but rather than ‘die by way of an eighty-year-old goatee’, she took the fatal step of lacing her grandfather’s omelette with veronal. ‘As I write, it is working. Maybe he is now already dead.’ Was it Charlotte Salomon writing these words? Or Charlotte Kann? Could she have killed him? Did she? Again, it’s impossible to know. There are logistical questions of dosage, the bitter taste of veronal, and timing. Is it a ‘confession’ that belongs to life – or to theatre? He ‘fell asleep gently by intoxication,’ the ‘confession’ continues, ‘and as I made a drawing of him, it felt to me as though a voice called out: Theatre is dead.’

Foenkinos passes over the confession in just a few lines: improbable and plausible; a novel within the novel. His narrative moves on to the last, dreadful months of Charlotte’s short life: her marriage to Nagler, their quiet life at Villefranche with a baby on the way, disrupted by the arrival of the Gestapo early one morning and the inevitable denouement of arrest, deportation: the murderous death from which there could be no return.

My first reading of Charlotte, was eager, and naive. I recommended it widely; at last the life of an artist who’d been under the radar for far too long. I had missed the 1998 exhibition of her work at London’s Royal Academy by a matter of months, and knew only the sketchiest outline of this elusive figure. Foenkinos has brought wide recognition to her name with a novel that has been, an international bestseller. That, surely, is an achievement. And if the novel was just that, a novel, it could be left there. But Foenkinos plays the double hand of granting himself the freedom of fiction, while laying claim to the life, as he puts it in the opening note, of ‘a German painter murdered at the age of twenty-six’.

My opinion of the novel changed when I began the exhilarating and exacting task of reading – if reading is the right word – the Duckworth edition of Life? or Theatre? Foenkinos’s ‘principal source’. To give him credit, he does grant that this extraordinary work is: A life put through the filter of creation. To produce a distortion of the real….

A few lines, that is all. For the rest, he uses it as an ‘autobiographical’ source. Reading Charlotte alongside Life? or Theatre?, it’s hard not to conclude that it is a sorely limited reading, a narrative smoothing into a Holocaust story that is at once familiar and affecting.

How much time did he spend with this complex, radical work?

It’s perhaps unfair to review Charlotte from the vantage point of Pollock’s very recent, magisterial study, published in April this year, the culmination of twenty years of thought and study. But even without her exhaustive analysis, it’s clear from the first image – the lake in which Charlotte Grunwald drowned – that Life? or Theatre? is not solely a Holocaust story. The family trauma dominates, the history of her abusive grandfather becomes increasingly obvious, hiding in plain sight, and as the horrors of Nazism close in, does he become an allegory? Is Charlotte Kann’s resistance to ‘Herr Ludwig’ and the brutality of the Everyday – the theatre of respectability – also resistance to ‘Herr Hitler’ and the monstrous theatre of Nazism and war? Is that its power, and its radicalism?

You will not find an answer in Charlotte. The urgency of Foenklinos’ style – those short sentences, each starting on a new line – draws us forward to the all-too-real tragedy of Charlotte Salomon’s death, but it falls far short of writing the art of her modernist masterpiece exhibited in its entirely for the first time a century after her birth in 1917.