We bought a little house in Laurieton almost two years ago. In that time, the town and the surrounding area have been threatened by fire, plague and flood. The local Services Club, a hundred metres away and a typical very large NSW Pokies Palace, was the local evacuation centre for both the fires and the flood and, in between, its car park has been a mobile health centre.

In times of disaster, ‘one’ (I use this term rather than ‘I’ for what follows) sees the community in its most comprehensive form, camping on the floors of the bars and the auditorium. Driven out of the caravan park and its provisional but permanent housing, which is check by jowl with the local oyster farm and the first to go under in any flood, are the poor – young and old. Young mothers (apparently single) with several children under five sitting in forlorn piles of doonas and disposable nappies and old couples badly compromised by various bodily and mental disasters struggle to look after each other. They are not the relatively well-off coastal retirees, who have been flooded out of their sessile homes and are now parked outside in their mobile homes using the club’s showers, toilets and washing resources.

This one (who is actually ‘I’) notes all this at the Club while having a late afternoon drink, and, writing this, ‘I’ (not ‘one’ anymore) am being the classic participant / observer of early twentieth-century social anthropology, what was to become sociology, and indulging in the writing position of many of the progressive writers of that time. (We might add some examples from centuries before: Defoe, Mayhew, even Marcus Clarke in writing about sleeping rough among the poor in Melbourne.) Many of the writers in this tradition in twentieth-century Australia were women: Katharine Susannah Prichard, Dymphna Cusack, Ruth Park, Eve Langley, Dorothy Hewett and Kylie Tennant. And yes, many of them were members of the Communist Party of Australia.

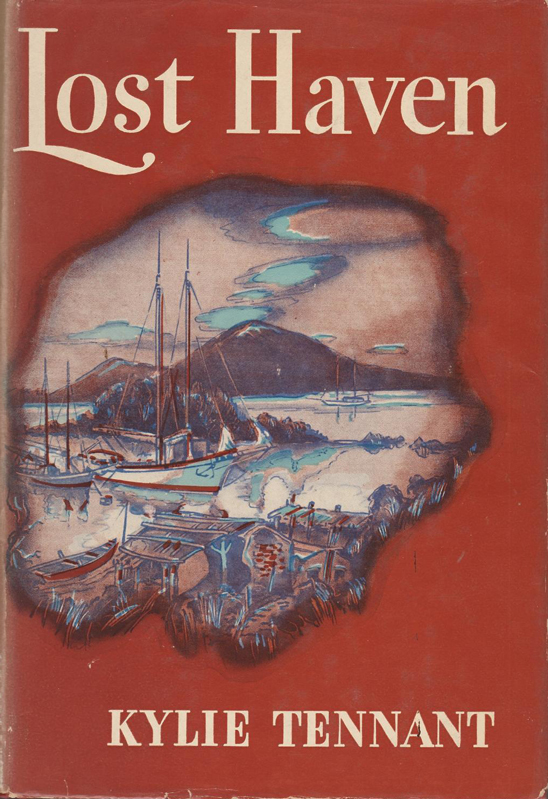

Lost Haven by Kylie Tennant is an account of that same community in the 1940, fittingly enough at my lifetime’s distance of eight decades. It involves, I would argue, that fraught stance of the participant / observer (one might note that the order changes often) and all the biases that were part of the same anthropological project (think of Malinovski and Margaret Mead). But Kylie Tennant didn’t pass herself off as an anthropologist; she was a novelist first and foremost. It would be easy to claim her a social realist – though not a Socialist realist, not ‘an engineer of the soul’, more a mechanic, as she renounced the Party almost as soon as she joined in the 1930s. I would see her more in the tradition of ‘documentary’ realism, following the aesthetic developed in the 1930s and 1940s in the new technologies of film and radio. The point about these technologies is that they offer a mimetic correspondence with reality. The camera doesn’t lie, or so it was once believed. But, say, in the case of film, those discrete ‘real’ images have to be put together, manipulated into a ‘story’ to make sense. The ‘observer / participant’ narrative stance, its use of ‘documentary realism’ and ‘story’, is what distinguishes Lost Haven, a nice 1940s combination of travelogue, romance, and national awareness.

If you haven’t read Lost Haven (and it is hard to get hold of even though it seems to have had a profitable publishing history with several editions here and abroad), here is a brief account. In 1941, Tennant’s teacher husband, Lewis Rodd, was transferred from Muswellbrook to Laurieton, where the family lived until he was transferred to Hunter’s Hill in Sydney in the early 1950s. As the Headmaster’s wife, Tennant had a privileged position in an isolated rural community in the Camden Haven, whose deep settler roots she outlines in the Prologue to the novel, which traces the competing family fortunes of the settlers through the nineteenth century to the present (war-time). The Prologue also contains rhapsodic descriptions of the physical environment and its effect on the local inhabitants.

The loveliness of the place is a faint, sweet corruption; old, grey, wooden wharves leaning drunkenly over the mud; old engine-boilers rusting on the edge of the channel; heaps of coal overgrown with convolvulus and lantana; old men sitting in the sun telling cruel stories. What is the use of working? The channel is silting up, and the bar grows more murderous every season. In winter, the lakes are full of red weed and slime which choke the nets and tear great holes in them. Or a wind is blowing. Sometimes two separate, rival winds will fight it out around Abraham [the local mountain], concentrating their fury over his foam-lashed lakes, meeting in eddies above the peaceful Bosom. Then it is better to idle in the sun, while the eye is lured away from a task by the stormy blue of the sea, the peach-blossom in grey rain, the silver flash of shoals. Even the slow perishing of a man’s means of livelihood may be of less account than a fish-hawk hovering. The contempt for work shown by every right-minded inhabitant of Lost Haven, the valuing of inertia for its own sake, are due to Mount Abraham leaning, breathing above the guarded peace of Abraham’s Bosom. Steamy rains wash from the soil all its strength, and from men’s minds all desire to be up and doing. Wrapped in a silken sheet of lakes, the mountain immense and grotesque, lies in its soft bed with the corrupt, idle town pressed to its side, a giant married to a fairy-tale princess.

But social and physical description are not enough for a novel; there must be a narrative to link the observations on community and environment. Thus we have storylines taken from Romance: the lost illegitimate daughter, a blonde, whose education in the city has turned her into a 1930s teenage socialite, who returns to her place of conception, unaware of the identity of her father. Opposing her is the young brunette librarian, quiet and domesticated, who comes to the town to be with her father, the local school teacher. The two, of course, are in love with the same young man. Add an outsider who is a government spy trying to track down an illicit still, the continuing feuds between two foundation families, and a careful accounting of the rituals, behaviour and speech of the locals. Tennant doesn’t miss a detail in her comprehensive capture of Laurieton in the 1940s.

That was partly the fascination for me, for despite the waves of retirees and outsiders in the past 70 years, the village and its inhabitants, unlike the major coastal towns, are still recognisable today. (As an aside, when the novel was published many of the locals rejoiced in the depiction of their own and themselves. Tennant records in her autobiography that Eddie Dobson, the model for Alec Suderman, read Lost Haven aloud to his children at night by the fire, noting that Eddie told her ‘When I came to me death, the tears were running down me cheeks.’)

Unlike her earlier novel The Battlers (1941), which used picaresque conventions as its narrative backbone, Lost Haven is loosely a family saga and a thwarted romance. Much of its power, though, comes from Tennant’s descriptive skills: not only her precise and sometimes overwhelming detail of weather, topography and botanical observation, but the variety of characters and the detailed record of their speech and behaviour (which some critics have found to be excessive). Allied with the close observation is a satiric, even comic, presentation of the human follies and vices in this lost haven. There is little sense that these people are being oppressed by social injustices and greedy capitalism, as in The Battlers. The local inhabitants are lazy, exploitative, greedy and amoral, but their treatment is an amused recording of human behaviour by someone outside the system, more Gulliver’s Travels than Pickwick Papers.

Perhaps that is where Tennant diverges from other social realist writers of the time. The issues for Katharine Susannah Prichard or Dymphna Cusack were too important to be played with. And that might explain why Patrick White was always friendly to Tennant (although, predictably, they later fell out) and put some store on her writing, which he must have seen was more than just ‘the dun-coloured offspring of journalistic realism’. Another close authorial friendship was with Elizabeth Harrower, a writer more interested in psychological reality than social issues, who must have felt some kinship with Tennant’s rather gothic imaginative processing of the ‘material’ she had set out to collect.

Tennant’s writing practice was often just that: going out and collecting ‘material’. While she was in Laurieton, she started work on her last major novel Tell Morning This, which is set in Sydney during World War Two – which, surprisingly, hardly figures in Lost Haven. Her preparation for the novel was very much in the style of anthropological research. In order to write about a quasi-criminal underclass, she needed to find out what being a prostitute was like from the inside. Taking leave of her husband in Laurieton, she spent time in Sydney with the aid of friends, dressing up as a prostitute, picking up men, sliding out of having to complete the transaction, and finally going to great lengths to get herself arrested so that she could spend a week in jail in order to find out what that was really like.

The result was a gigantic novel, which her publisher Macmillan refused to publish unless she dramatically reduced its length. The reason, they said, was that they couldn’t afford the paper! The truncated version was published as The Joyful Condemned in 1955, and the full-length version by Angus and Robertson in 1967. It could be argued that its faults are its length and the overwhelming array of characters; however, it does illustrate Tennant’s approach to fiction. It must be based on first-hand experience, and in that regard she saw herself as a journalist, but it is not ‘dun-coloured’. She writes with energy and brilliant visual sense, which I imagine must have appealed to the painter manqué White. Once she had experienced being a ‘bag-man’, ‘traveller’, ‘swagman’, she could write honestly and amusingly in a self-deprecating way about social issues in The Battlers, just as she was to do with the citizens of Laurieton, whose lives she shared for almost ten years. Yet she felt compelled to wrap up those observations in the sort of metaphysical haze which, again, would have appealed to White. You can see it in the title of the book with its echoes of something very profound, and likewise in the gnomic title of her last major novel Tell Morning This, the relevance of which always defeated me, but suited the tenor of the times when popular novels often had obscure metaphorical titles.

What is intriguing about Lost Haven is its publishing history. One might think that the detailed depiction of the ‘colourful’ lives of rural Australians might appeal to the home audience, but Lost Haven was published by Macmillan in London and New York (and was reviewed by Christina Stead in The New York Times). I imagine it was partly because of Tennant’s reputation as saleable. The Battlers had had US and UK publishers (Macmillan in the US and Gollancz in the UK); it had won the Australian Literature Society Gold medal in 1941 and the SH Prior Prize. It was republished in Australia in 1945, and again by Macmillan in 1954. Translations were published in France in 1955 (Les Trimadeurs) and in Zürich in 1957 (Fahrendes Volk). Pan brought out a UK edition in 1961 and it was reissued yet again in Australia by Angus & Roberston in 1965. Perhaps Lost Haven’s attraction was the popularity of Depression-era Okie documentary novels in the US, though Tennant hated being compared to Steinbeck, or for the UK market the post-war interest in Australian emigration, as well the well-worn and still current tradition of the village novel with colourful characters which persists to this day on TV (Doc Martin is one recent example).

Margaret Dick, in her book length study of Tennant’s novels published in 1966, saw Lost Haven as a maturing step away from the ‘austerity’ of Ride on Stranger towards ‘a resurgence of a poetic, instinctive response to nature and a freer handling of emotion, an unselfconscious acceptance of the existence of grief and despair’. This was a necessary step towards the maturity of what Dick considered Tennant’s best novel (and I would agree) Tell Morning This.

I wonder if part of this was to do with Tennant living as a settled, rather than a transitory, participant / observer in the community she is using for her ‘material’. In The Battlers, it seems to me, two groups provide her material: her fellow travellers (a laden phrase in the 1930s) and the communities they interact with. The participant / observer position is hard to sustain, as her sympathies and point of view are located in the itinerants and they are described much as she does her own family in her autobiography. The town communities are the ‘other’, much as school, workplace and suburb are in her autobiography. In Lost Haven, Tennant was on firmer ground as an integrated member of the community, with a recognised position as ‘headmaster’s wife’, while being also its annalist and chronicler. This enabled her to indulge her comic and serious sides in what Dick called ‘a freer handling of emotion’. The roles of participant and observer had more clarity in the Laurieton setting where she lived for eleven years than in any of the other realms where she collected material for her novels. Unlike the harsh realities of inland New South Wales seen in The Battlers, Lost Haven seems a paradise, though an ‘unpredictable’ one, as Dick suggests:

In this unpredictable paradise the Tawneys and Starbraces, the Detwinters, Sudermans, and Thornes catch fish, work in the mill, marry or take mistresses, bear children, nurse hatred, drink and brawl or, best of all, lie in the sun and watch Alec build his boat.

Building the boat is akin to writing the novel – and indeed Tennant spent hours working with Dobson the boat builder learning how to caulk and plane – for it is the vessel of liberation. It is something creative made despite the sloth of quotidian habit, which so many of the inhabitants of Lost Haven seem to suffer. For the inhabitants, it is enough just to watch – no one helps Alec. In Tennant’s case, her domestic help – one of the ‘less able’ girls from the next-door school – reported to the town that ‘Mrs Rodd does nothing all day but lie on a bed and read’. But like the snapper boat on Alec’s slips, something does get finished, in this case Tennant’s history of Australia, which she was researching as she was writing Lost Haven.

Living in a tight community brought with it responsibilities. Some of the issues Tennant faced in Laurieton can be seen in her memoir of her time there and her essay of thanks to Ernie Metcalfe, the man who built her retreat at Diamond Head. The hut unfortunately perished in last year’s terrible fires, but a project is underway to re-build Kylie’s Hut, as it is called, next to, of course, Kylie’s Beach. But even in this work of genuine friendship and sympathy for Metcalfe, his family, and the community he lived in, one can sense the distance of the observer, despite the obvious personal bond she feels for Ernie, a representative of a vanishing Australian rural worker.

That distancing, the stance of the alien anthropologist in the village, has to do with class. Tennant grew up in Manly with warring but relatively well-off parents. Her father was an executive in Lysaghts and mixed in a conservative political circle at the highest level. Her mother came from well-off local builders. Her husband was a headmaster, and she prided herself on always having been able to earn an income of her own from her writing, which seems to have been remarkably lucrative. Out on the track with her horse and cart, when she strangled her horse by mistakenly tying her up with a slip-knot, a disaster for any other itinerant, she could pack up and go home to Sydney. In Laurieton, if she wanted to research a novel in Sydney during the war, she could decamp, spend months there and a week in jail under a false name, and then come home. Later, she could buy a truck and go out and follow the honey flow in the New England ranges, then come home and write. She had a freedom none of her neighbours and subjects could dream about. The flow of novels stopped, of course, as everyone warned her and she herself knew, when the children came in 1946 and 1951. She was no longer the free-spirit observer, but the earth-bound participant.

The Rodds moved to Hunter’s Hill in 1952, but Tennant kept coming back to Laurieton, rather Diamond Head, to her hut, which served as a retreat for her and the children. After various disasters in the 1970s, she lost her husband and her son in 1979. Blackheath in the Blue Mountains became her refuge. But as we can see from The Man on the Headland the Camden Haven and its inhabitants remained a constant source of inspiration, which is not surprising as those eleven years in Laurieton were the most settled and productive in her life. As for me, reading Lost Haven in this particular place and time made me reflect on the nature of documentary realism (not for the first time), the intellectual traditions of the early twentieth century, and the way in which the women writers of that time constructed their position as writers, and the aesthetic decisions they made about how they went about processing their ‘material’. It gave me a firmer footing in a time of flood and fire to see what was or ‘might be’ (another thing Kylie’s writing and life taught me – everything is provisional) going on around me.