For centuries, pirates have captured the imaginations of both children and adults. The swashbuckling adventures of Long John Silver, Calico Jack and Captain Hook have won legions of fans, who dream of their dashing adventures across the high seas. We can now add Pen Davenport, the protagonist of Matthew Pearl’s latest novel The Last Bookaneer (2015), to the list of notorious pirates. Unlike his predecessors, however, Davenport’s interests lie not in piracy at sea, but in an illicit trade known as ‘bookaneering’ – flogging stolen copies of novels and other creative works to punters keen for a bargain.

The Last Bookaneer examines a legal and cultural context that will be familiar to those with an interest in the history of book publishing and copyright. Set in the twilight years of the nineteenth century, a lawless era when the United States and England did not legally recognise the intellectual property of the other nation’s writers, the story follows Davenport’s dastardly attempts to steal a manuscript from the dying Robert Louis Stevenson, who is desperately trying to finish his last novel at his island residence in Samoa. For Davenport, the stakes are high. There is talk of an International Copyright Act, so he must steal Stevenson’s pages before the lawyers swoop.

Pearl’s book is a reminder that intellectual theft was an issue long before the arrival of e-books and internet piracy. As Pearl explains in the afterword, the nineteenth century had its own breed of literary pirates, who used the technological advances of their age to steal and swindle. Publishers and bandits alike pilfered, pillaged and reprinted creative works, on-selling them without recompense or care for the author. It took the International Copyright Act of 1891 to curb the trade, but, as we now know, the Act and its subsequent amendments have been unable to curtail what has now become a rampant culture of intellectual property theft.

Yet there are encouraging signs of late that, after years of lobbying, legislators are finally beginning to take the matter seriously. In England last month, the UK Publishers Association’s won a high court case that will force the country’s five main internet service providers to block consumer access to websites that promote the online theft of e-books. In a country where over ‘80 per cent of the material available on the sites (and in some cases over 90%) infringes copyright’, this is a win for publishers, writers and the general health of literary culture, particularly given the shocking findings reported by the Publishers’ Association during its investigations:

Collectively The PA and its members have issued nearly one million take down requests to these sites in respect of their content. In addition, rights owners have requested that Google remove from its search results over 1.75 million URLs which link to copyright protected material on these sites.

Between them the sites purport to hold around 10 000 000 ebook titles and have been making substantial sums of money, primarily through referral fees and advertising. None of this money has been going back to either the publisher or the author(s) of the works.

The UK legislation is also a win for Australian writers and publishers: the UK sites AvaxHome, Bookfi, Bookre, Ebookee, Freebookspot, Freshwap and LibGen, all of which are currently accessible from Australia, feature pirated e-books from Australian authors, including Tim Winton and Fiona McIntosh. It also sets a useful precedent as Australia considers its own approach to internet piracy. Only yesterday, the country moved a step closer to enshrining in law the Copyright Amendment (Online Infringement) Bill 2015, after a federal parliamentary committee gave the Bill the green light. As in the UK, the law will allow Australian publishers to apply through the courts to block online sites that facilitate the pirating of intellectual property. The Bill has been the subject of considerable debate, with the Greens, Choice and ACCAN concerned it will lead to the blocking of innocuous sites. Yet it is clear that something needs to be done to address the ramifications of illegal downloading and internet piracy. In Australia alone, recent estimates suggest that online piracy has cost the local economy more than $1.3 billion in the last twelve months.

The Last Bookaneer has Davenport stealing a physical copy of Stevenson’s handwritten manuscript, forcing him to at least come into contact with the writer; online technologies and the digitised form of most books tends to distance modern pirates from the lived and felt experience of the writer and his or her publisher. As numerous threads on internet chat sites reveal, many consumers of pirated material seem to be no closer than their nineteenth-century counterparts to understanding how copyright theft effects the creative economy. As Pearl writes in an article for The Huffington Post, prominent authors who complained about the illegal trade in the 1800s were often subjected to the same brand of caustic criticism directed at artists today when they speak up about the illegal downloading of their work. Authors such as James Fenimore Cooper, Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Charles Dickens, who tried to fight the system, were ‘shouted down as avaricious, and they often nervously retreated from the fight.’

The contemporary problem of trading proofs and draft versions of a work was also a concern. Copies of unedited or unpolished work were often at risk of theft and circulation. The ‘bookaneers’ even sometimes modified or corrupted content, a famous case in point being the New York publisher Hurst & Co. misspelling Robert Louis Stevenson’s last name as ‘Stephenson’.

As in the nineteenth century, it is still difficult for writers to maintain a livelihood and collect adequate fees for the work that they do. As Phillipa McGuinness notes in the new collection Copyfight (2015), we need to bring the voices of artists and publishers back into the story so that the culture can step away from ‘normalising’ online pirating.

Until then, while we wait for the new laws to take effect, lovers of book culture could take solace in the work of self-described ‘anti-pirate’ Tafun Şahin, a Turkish author and bookstore owner, who has found his own unique way of confronting book piracy. Şahin invites residents of the northwestern province of Tekirdağ who are in possession of pirated books to bring evidence of the illegal trade to his shop, including specific details of where the pirated copy was purchased. The paperwork is traded for an original copy of the book – at no charge. Sahin then reports the illegal download sites to the authorities. ‘Eighty percent of people [in Turkey] do not know they are reading pirated books’, he told Daily Sabah: ‘I want to plant this idea in to future generations … If you are sure that the book you bought is pirated, I will give you the original copy without asking for a fee … All I want to learn is the place that they bought the pirated books from.’

This week the Sydney Review of Books features Emmett Stinson’s review of Tom McCarthy’s new novel Satin Island. Stinson begins his essay with a reference to Seinfeld, the ‘show about nothing’, which he uses as a counterpoint to Satin Island’s protagonist U., an anthropologist and follower of Levi-Strauss, ‘who is desperately trying to finish a book about everything’ – and failing. Like McCarthy’s earlier novel C, Satin Island is replete with intertextual references, which inform his satirical critique of corporations, high theory and the academy. Yet for Stinson the satire lacks bite:

the claims that academics are essentially bourgeois knowledge-workers and that corporations increasingly generate and traffic in knowledge or ‘immaterial’ forms of labour are insights autonomous Marxism developed more than 40 years ago. The same holds for the novel’s depiction of ‘left-wing’ critical theory as an R & D sector of the very multinational capitalism it seeks to critique …

If McCarthy simply wants to broadcast these critiques to a broader audience, then fair enough, but the problem is that he seems keen, as Satin Island’s acknowledgments suggest, to court a certain type of ‘critical’ reader. I suspect many such readers will respond like the fast-food worker in Dude, Where’s My Car (2000): ‘And then …?’

Our second essay is a review of Devadatta’s Poems, the most recent collection from the 2015 Peter Porter Poetry Prize winner Judith Beveridge. In ‘A Test of Arms’, Ann Vickery traces Beveridge’s ongoing interest in Buddhism, which she explores in the voice of Devadatta, the narcissistic rival of the famous Siddhattha. As Vickery notes, Beveridge takes Devadatta from the the margins and places him at the centre of her volume, ‘aestheticis[ing] both Devadatta and Siddhattha through a rich lyric narrative’. In Beveridge’s poetry, argues Vickery, ‘words themselves are mobile, pleasurable forces’.

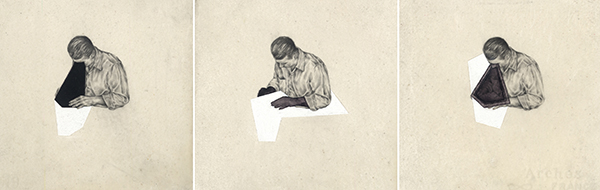

From the Archives revisits an essay on four Australian debut novelists, considering their work against the backdrop of the cultural and economic forces that shape the careers of new and emerging writers. Given the meteoric rise of two of the authors, Graeme Simsion and Hannah Kent, ‘So Many Paths that Wind and Wind’ by Stuart Glover is well worth re-reading. Our image this week is part of a striking triptych by Teo Treloar titled ‘Repeater’. The drawing is included in a new exhibition at the Flinders Street Gallery in Surry Hills. You can read about some of Treloar’s earlier work and his approach in a short archived interview with the Art Collector’s Jane O’Sullivan.