Women lust and die in Robert Hillman’s Joyful, but not, it would appear, in the classic realist novel manner. Where a heroine such as Emma Bovary yearns, is seduced, and falls from grace, Joyful offers a twenty-first century update on that scenario. Women still die, but it is the men who love longest when all hope is gone (to turn-about what Anne says in Jane Austen’s Persuasion). It is men who are driven mad by their love-lost grief, and men whose madness leads to an almighty – albeit self-inflicted – fall from grace. Unlike poor old Charles in Madame Bovary, men experience passionate madness in the wake of a grand amour that is pathetic but not bathetic. Hillman’s mad men are self-obsessed, but they are not objects of ridicule.

This strange novel is Hillman’s fifth. He is best-known for his memoir, The Boy in the Green Suit (2003), which won the National Biography Award in 2005, his biography of the Aboriginal musician Gurrumul (2013), and also for refugee and migrant stories, such as The Rugmaker of Mazar-e-Sharif (2009), co-written with Najaf Mazari. He has talked about his interest in the marginalised and socially disadvantaged, as well as what he calls ‘the mayhem caused by big egos on the more modest egos around them’. Commenting on his own fiction, he has written about a novelist’s ‘frenzies and phobias and unexamined prejudices’ and there do appear to be quite a few of these bubbling away within the thick and not-altogether-wholesome brew that is Joyful. Hillman also notes that where he has long been ‘attracted to hopeless quests, chimeras, characters who are half human, half monster’, his interest in happy endings is ‘quite new’.

From the start of Joyful, the happy ending seems inevitable – that is, the survival and recovery of the two men whose grief-induced madness is linked in time, place and coincidence of association. This is not to say that the novel is not pulled along dramatically towards its conclusion, just that the conclusion is no surprise (although there are many surprises along the way), given how the male and female characters are set up from the start. There is nothing timid or modest about this storytelling; it blasts us with a symphony of unhappiness and folly. But everything tells us that Leon and Emmanuel will survive.

That they survive, in each case, because of the faithful patience and devotion of a woman is, I think, of particular interest to any reader keen to join the novelist in his backward glance at his writings to identify its ‘frenzies and phobias and unexamined prejudices’. While Hillman stacks up a number of counter-measures to traditional masculinist narratives in which fallen women must die, these are for the most part window-dressing. Inside his fictional house, the same old essentialist judgements about men and women are being written all over the walls and floors – literally, in Leon’s case. Despite what appear to be subversions of conventional role divisions, this is not a novel to read if you want women characters who are more than constructions of a masculine imagination.

It is interesting to go from this teasing, puzzling novel, with its sometimes cruel and judgmental depictions of women seen through the eyes of men in crisis, back to The Boy in the Green Suit. That memoir, particularly in the biting opening chapters, but continuing right through to Hillman’s return from a dangerous year travelling as a teenager in the 1960s, is haunted by one image – a woman in a red coat walking away from her needy child. Joyful reads like the novelist’s revenge.

It begins with the death of Tess, who has been married for less than two years to Leon, a wealthy Melbourne bookseller. She is about 40 when she meets Leon, and only 43 when she dies from cancer. On her deathbed, as described in the prelude, ‘Nothing was left of her beauty.’ With Tess dead, the only way we are able to get an idea of how she behaved and what she thought is through the memories of others (although we do hear her voice, first in a written interchange with Leon as they contemplate marriage, and then, about halfway through the book, in a series of emails she sent a lover, which Leon accesses in an unlikely way). On the opening page, however, we have omniscient narration that takes in several of points of view. Leon is by the dying Tess’s bed, as are her son, Justin, and her daughter, Evie. Presiding over the last rites is Father Bourke, who croons to Tess as much like a lover (which he turns out to be) as a priest. As he lays out the paraphernalia for the Catholic ceremony, ‘Tess watche[s] in dread’, which shifts us for a moment into Tess’s thoughts. Then we are out again, watching Father Bourke kiss her fingertips, hearing him intone the words of the ritual, seeing her ‘appear to take something’ from the priest’s pronouncement that ‘Lovely, the dying part is piffle’.

Then, momentarily, back inside the characters we go, to share the privilege of that knowledge with the narrator: ‘The authority of the priest had settled a spell on all those kneeling, leaving them mute of thought.’

Three pages of preface and Tess is dead. Her sins are absolved, according to her religion, by the communion prayer, which includes the phrase ‘Happy are those who are called to His supper’. And so we launch into the story suspecting it will be about Leon, but also knowing that he was hardly present for Tess at her death, sidelined by the imposing figure of the priest. We witness a death that is not just sad, but somehow unsettling. It would seem there is much to be done, much to go through, before Tess can be forgiven by other than God. That is probably a blasphemous thought, and there is certainly a challenge to doctrinal religion running through this novel, but it is always ambiguous. It is more an invitation to consider than a position taken, although how belief and religion sustain people and are used by them is part of the story’s framework.

For Leon, we soon discover, Tess is his religion, the icon of his cult. Plato’s aphoristic statement on beauty is used as an epigraph to the novel: ‘Beauty is certainly a soft, smooth, slippery thing, and therefore of a nature which easily slips in and permeates our souls. For I affirm that the good is the beautiful.’ What Leon goes through, and what he comes to finally realise, is a means of scrutinising that notion of the good as beautiful – or rather, it challenges the inverse idea, that the beautiful is good.

Tess is a famous beauty, and famously promiscuous. She is a pianist and teacher, who has a program on ABC radio which has made her very popular. When she meets Leon, who runs a bookshop for collectors, it is not clear why she responds to his interest, except that it seems she finds it hard to resist the attentions of any man.

Leon has lots of family money and assets, including a property in country Victoria called Joyful, which he has inherited but never visited. His wealth means he can also indulge his unusual passion for expensive women’s clothing, which he keeps in a kind of gallery space at his home. He occasionally brings women there to dress them in Givenchy, Jacques Fath, Schiaparelli, Ungaro, Madame Gres, and so on. He is not interested in sex – at all. What sends him into ecstasy is being able to contemplate a beautiful woman wearing a beautiful frock. When Tess tries to seduce him, he is disgusted and explains that, ever since his experience as a boy watching the lovely Aunt Sarah dress up and seek his approval before she sallied forth for the day, he was always seeking that same overwhelming joy. Sarah is one of two significant suiciding women in Joyful.

Tess puts on a ‘golden gown in silk jersey with a high, oriental collar’, adds Zanotti shoes and a grey silk scarf, poses in exactly the way Leon instructs – it’s good, but not transporting. So on goes a Bill Blass, ‘in yellow silk crepe with a cyclamen bodice’ with matt-yellow stilettos in painted kid and jet earrings. Leon instructs her to sit in a Saarinen chair, gaze out the window:

imagine that you are far from bored, but wish to appear so. Throw your shoulders back so that your bosom holds the bodice line more firmly. Hold the tips of the fingers of one hand in the tips of the other behind the chair. Just the tips of the fingers!

Tess says he is being bossy – this is an important word for Hillman, ambiguous like many of the ideas he lays out, but more positive than negative – but on he goes, until finally a Ralph Lauren black cashmere halter neck does the trick. Leon is moved to tears.

For those of us uninterested in frocks, the good news is there is very little dressing up in the rest of the book. Tess divorces her Polish husband, who is violent and unfaithful (although Evie will undermine Tess’s version of this later on), and agrees to marry besotted Leon, on the understanding that she is still interested in sex, if not with him, then with others.

Leon is an ambitiously-created character. Asexual and passionate, he is also both ascetic and sensual, compliant and demanding. We have to believe that his adoration of beauty turns into an addiction to the person who is Tess, and that this addiction then creates a madness of grief following her death. Like Charles Bovary, who refuses to accept that Emma is anything but the uncomplicated, beautiful girl he lifted out of relative poverty into mediocrity, Leon wants to live out his days fetishising objects his beloved had once touched. When, however, it is revealed that Tess in fact had a tempestuous affair with a hyper-masculine Pole named Daniel throughout most of her short marriage to Leon, his grief tips towards insanity.

Polish people do not fare well in Joyful. Tess’s first husband was also Polish, and she claimed he beat her. Coincidently, perhaps, a Polish couple also figure in a sad episode in The Boy in the Green Suit. They are childless, and they look after the young Robert occasionally when his father and sister go off to Melbourne for a couple of days. Though they are kind, they are distant and not warm. Robert remembers this ‘couple of peculiar old people dressed in humourless grey left weirdly watching over me’ as baffling, until, twenty years later, he brings it up with his sister. He discovers that his father had wanted to adopt him out to the Polish couple, a discovery he admits he was not prepared for, even at 27. Hillman gets a kind of private revenge on these Poles who are retrospectively so scary, linking them by nationality to the dishonest and monstrously selfish Daniel.

Leon’s discovery of Tess’s flagrant betrayal sends him north to Yackandandah, near Beechworth, with the vague idea of reclaiming his wife’s memory from the man who had been her physical lover. And that takes him to Joyful, where he will confront the goatish Daniel, discover the story of his great-aunt Jennifer and the religious utopian community that existed at Joyful in the 1940s and 1950s, and re-encounter Emmanuel and Daanya Delli, who are also grieving. This couple had known Tess through their daughter Sofia, a musician and fan of Tess. He is a university professor; she is a paediatrician. Both are refugees from Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, where they witnessed terrible violence and experienced personal danger. Their son, Joseph, was killed in Iraq. Then, in Melbourne, their daughter kills herself following an affair with her father’s friend and colleague.

Hillman does not muck about with the murky psychoanalytic motivations behind Emmanuel’s dreadful labelling of his beloved Sofia as a whore to disguise or exacerbate the roaring grief that engulfs him in the wake of her death. He has a ‘bossy psychotherapist from Thailand who was also a practising Buddhist’ suggest to Emmanuel that Sofia’s affair with her father’s closest friend had been a way of trying to act out the impossible – her love for her father. ‘Sofia had known the relationship with Averescu was hopeless,’ the narrator tells us, paraphrasing what the bossy psychotherapist has told Emmanuel, ‘but that the sheer impossibility of fulfilment had perfectly mirrored the impossibility of fulfilment in the desired union with her father.’ Sofia cherished death, as an approximation of the ‘complete consummation’ she desired.

A father who was told this and who might suspect it for himself could, indeed, be driven to guilt-inspired madness. It’s tragic stuff. This daughter burnt on the pyre of her father’s love and ego makes me think of that fabulous painting by French symbolist Gustave Moreau, of Jupiter and Semele, where the frail beautiful woman expires on the knee of the god in a swoon before his powerful sexual presence. She, apparently, is a symbol of regeneration in that painting, although it is hard to go past the sensuality of her death by domination.

Hillman, disturbingly, describes the way Sofia straps a razor to a hotel bath tap to slice her veins in view of the office where her lover works, so he is careful not to eroticise the actual death. When back we go to Emmanuel, to work through the depths of his anguish with him, it is tough reading. He becomes a monster of abuse and offence. He finds a kind of perverse joy in sending disgusting emails to Averescu, which only stop when he learns of his former friend’s death and his wife rips out the computer cord before he can send a grotesque email to Averescu’s daughter. To his wife, he is despicable. He belittles her, calls her names and physically threatens her:

Delli seized his wife by the face and squeezed her cheeks between his fingers until her lips were bunched like bleeding fruit. ‘Do you know how easily I could kill you? I could tear your face from your skull if I wished.’

Daanya takes it all stoically, remaining loyal to the man who was her husband before he morphed into this violent lunatic, but she knows his rage could flame up into an inferno and she could die in its heat.

What is to be done? How would you cope? I found this all very confronting, particularly against the backdrop of media discussions about domestic violence. Consequently, I am puzzled by the publisher’s description of Joyful as a ‘comedy of grief’.

Leon is as interested in killing himself as Emmanuel, but his madness takes a different form. He is certainly not fantasising about taking anyone – man or woman – with him. Except maybe Tess, and therein lies his problem. He enters into an agreement with Daniel and another couple who are drawn into Daniel’s lascivious circle; he tries to buy back his wife’s memory. When that fails, he takes to writing to his dead wife – all over the floors and walls of the mansion he has inherited. He has also inherited a propensity to grand-amour intensity. His mother had it to a small degree and his great-aunt too, as he discovers when a woman researching utopias for her university thesis contacts him to tell him about the diaries she has found, written by that great-aunt.

Hillman draws a parallel between great-aunt Jennifer and the two mad men, giving her a grand amour for which she says she would be willing to die. The loved one, a much younger man named David, dies too, like Sofia and Tess. He dies in a fire, killed not by Jennifer but by his wife, who is apparently driven mad by his infidelity. We don’t get much of that wife’s story, as she is incidental to the plot, and it does feel that she is a handy device, rather than a believable character.

This is what I mean when I suggest that what may appear to be subversions of masculinist narratives do not go further than window-dressing. Other women in the story are also handy and somewhat incidental. These women – such as Tess’s daughter Evie and Leon’s faithful shop manager and saviour, Susie – are caricatures of the feminine. Evie and Susie are both bossy women described in snatches of summarising description. Evie is Tess’s plain daughter, and she is a bit of a mess but sort of practical. She gets her own brief chapter, when Leon goes to her to find out about Daniel, in which she talks about her failing marriage and her own concerns. ‘Leon listened, feeling sorry for her in the way he always had,’ the narrator tells us, ‘because nobody would ever love her very much, or not for long. Men were appalled when she took a holiday from bossiness and begged for affection.’

The coincidence of points of view happens again here. Leon’s perspective and that of the omniscient narrator, are lined up in a way that is ambiguous, a way that may or may not be condoning or agreeing with what Leon thinks. It is a nasty thing to say about this young woman, but Leon is judgmental when a person is demanding something of him that he finds distasteful. Evie ends up as mistress to a much older Chinese man, and she sends a message to Leon from Shanghai describing ‘being a mistress’ as ‘heaven at the moment, free trip to China, hotel on the Bund’. We get no comment from Leon about this venal behaviour, which uses sex as a means of material gain. This female character, glimpsed briefly, has no depth, no development; her role is to move the plot at important points, but also to appear as an example of a feminine type. Minor characters who are men are treated similarly, up to a point, but they live a little more fully. They exist beyond the scrutiny of Leon or Emmanuel.

Later, the woman who was part of Daniel’s virtual harem in Yackandandah, makes a pathetic attempt to seduce Leon in the hope he will not do anything to force Daniel to leave, and here, through Leon’s eyes, we see this naked woman as an object judged harshly:

The feature of Emily’s nakedness that saved Leon from giving way to anger was her extraordinary mass of dark pubic hair, luxuriant enough for her to tie it with ribbons if she’d wished. It imparted a biscuity wholesomeness and made her more nudist than seductress. Leon noticed, with an interest that lasted half a second, the peculiar deepening of Emily’s hair colouring running from crown to crotch, hazel topmost, then the solid brown hue of her eyebrows, finally sable. For a few months of Leon’s marriage, Tess had favoured the girleen look of a waxed pubic area, but it required too much maintenance for her to persist with it and she’d given it up with glee at about the time she’d met Daniel. So this must be his taste, Daniel’s taste: the free-range female groin.

Again, this is venting Leon’s misogyny in a way that does not judge him but almost colludes with him, as he objectifies the unadorned female body with distaste. Maybe this is an example of the ‘comedy of grief’. If so, the humour is peculiar.

In The Boy in the Green Suit, Hillman’s sixteen-year-old self yearns for the ideal feminine. His town, Eildon, was changed irrevocably when American engineers and workmen moved in to create the massive dam. All the tensions of this ordinary Australian 1950s town are cranked up, and marriages disintegrate. He witnesses

strange dramas that cast my parents in roles that could not have frightened me more if the props had included bleeding goats’ heads mounted on stakes. My father holding the neck of a broken beer bottle to his own throat, while my mother, perfecting an expression of supreme uninterest, shelled peas at the kitchen table. My mother at the stove, dreamily placing the tip of one finger on the hotplate, flinching and shaking her hand rapidly in the air, then trying another finger, and another.

Tess does something similar in Joyful, burning her fingertips to inflict pain, but in a distracted manner.

In The Boy in the Green Suit, Robert’s mother leaves, ‘dressed in a beautiful red overcoat, one I had always admired.’ She walks out and appears not to have looked back, only contacting the siblings 25 years later when Robert’s sister Marion puts advertisements in newspapers. A visit to his mother some years later is described with controlled irony that barely disguises his disgust at her astonishing hypocrisy. This dramatic woman, who lives among a confusion of red and black dragon figurines and wears purple and gold shawls, lectures him on why he must ‘open [his] arms to love’:

‘Be very careful,’ my mother says, ‘with the people who love you. More careful than you’ve been, so far. That’s all.’

Hillman’s father, hardworking but eventually ‘broken in spirit by the ugly failure of his marriages’, had held in his imagination his own feminine ideal: ‘women who minister to him tenderly after battles, bind his wounds, sing him songs, disrobe at a word of suggestion and croon at his touch.’ It was in search of ‘dusky versions of this accomplished, uncomplaining, eternally tender strain’ that the young Robert headed off on a ship bound, he hoped, for the Seychelles. He has to disembark in Greece and travels on to Iran and Kuwait, where he stays for some months on a roller-coaster ride that is comic in its risky naivety. He is propositioned by wealthy powerful men and bought a prostitute by a group of young men he is supposed to be teaching English. He claims, however, that much of the cultural experience passes him by as he is driven by the ‘same old thing: scrounging for love’.

The last pages of The Boy in the Green Suit seep with the sadness that pervades this memoir. Hillman often goes to visit his father’s grave, sometimes with companions who are bemused by his sentimentality. He gives the final line to a woman from the town who is visiting the grave of her son. (Hillman remembers he put that son in a novel, ‘with a cavalier disregard for the feelings of his family’.) When the woman, Madge, is amazed to recognise the man returned to his childhood home, she says, ‘You’re Frank Hillman’s boy, aren’t you?’ This is not just a poignant remembrance of things past; it is the author’s recognition that he may not be able to escape his father’s legacy.

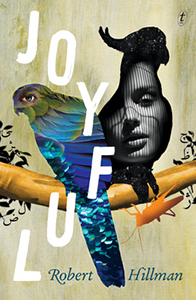

The echoes from The Boy in the Green Suit that can be heard in Joyful include such small details as the significance of the colour green: in the memoir there is the ‘lazy green valley’ of his childhood town, that famous green suit he wears as he goes off in search of love, and the fabulous green islands of his and his father’s imagination, where dusky maidens offer themselves up like fruit. In Joyful, the ‘chattering green parrots’ (which appear on the cover) feature in the novel’s climax on the anniversary of Tess’s death, when Leon’s madness is about to reach a crisis. At this moment, the green parrots are described as ‘just waiting … for some sort of signal maybe.’

Leon fails to burn the house down around him. Instead, the parrots fly off and Susie arrives, the Burmese woman who manages his bookshop and whom he loves in his own odd fashion. Susie has supported him throughout, even though she knew all along Tess treated him with disdain. It is Susie’s ‘natural bossiness’ which is exactly what Leon craves.

The feminine ideal, then, finally comes into focus in this image of Susie, who is ready to sort out Leon’s needs, and look lovely while she does it. Its opposite, the feminine ‘vampire’ as Emmanuel calls Tess, is symbolised in an image that describes Tess’s kind of beauty as dangerous. Shortly before his ‘rescue’, Leon finds an animal trap out in the paddocks around Joyful:

The trap had been there for a very long time, its jaws and spring and the chain that tethered it to a metal stake all crusted with rust. … the rust had eaten away the harm stored in the mechanism.

Leon takes it inside, to the kitchen table where ‘All around it swarmed his messages to Tess.’ He examines it the way he examines his rare books, and is reminded of one of those books in which all kinds of terrible traps are depicted, ‘traps designed to close on human legs at knee-height; on necks, hands; to thrust a spiked ball into the genitals; to hold a bear by its snout.’ Then, as he contemplates this rusted trap, he has an epiphany:

It was the arrested harm in the trap that so fascinated him: the leg that wasn’t crushed, the scream that did not join the great volume of screams erupting constantly all around the world. There was beauty in damage averted; beauty in the rusting shut of any entrance to hell, even the hell of anonymous beasts. The beauty transmitted itself to Leon’s fingertip.

Daniel’s explicit and crude descriptions of Tess as the embodiment of that age-old symbol of masculine fear, the vagina dentata, has set us up for this ambiguous moment, when beauty – that ‘soft, smooth, slippery thing’, as Plato called it – is redefined as ‘damage averted’. And there are those fingertips again, more important as the sensors of truth than the eyes, but delicate and so much more sensitive to nuance than the coarse frotting of sex. As the days pass by, haunted by his memories and sunk in melancholy, Leon stands in the room where he had seen Emmanuel – or perhaps some other ghostly figure, Jennifer maybe, or Tess – weeping. ‘He always brought the animal trap with him to caress in the darkness. It was his last consolation in life, the steel jaws that could never close again.’ It turns out not to be his last consolation, in fact: Susie and her bossiness are.

It is a rocky ride, this journey to Joyful, where passion runs riot and madness overpowers emotions. It is anchored, however, in the cool appraisal of the feminine, which surfaces by way of judgemental descriptions of women, their looks and their behaviours, and also the misogynous opinions and actions of the male characters. While the need for masculine and feminine co-dependence is played out in many forms, no woman is allowed independence from her destiny as handmaiden. To achieve joyfulness, the novel implies, men and women must accept, with humility, their essential beings.