Comics seem to find critical acclaim in the mainstream only under certain conditions. First, they must deal with bleakly mature themes. Second, they must do so in a cartoony style that belies their seriousness, to paraphrase their mainstream reviewers. (What comics style isn’t somehow cartoony?) The graphic novel section in any given bookstore thus leans towards warzone journalism, family drama and wrenching confessionals. Despite constant reminders that comics have grown up, the non-comics reading public probably picture them less as a medium fulfilling its potential, than as one held back after class and tasked with writing multiple essays on very heady topics, as punishment for earlier mischief-making.

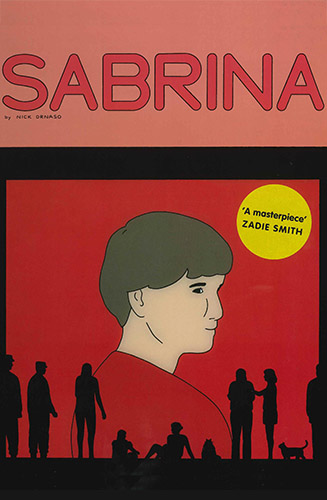

Cementing but also subverting this image is Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, which, in a first for comics, was longlisted for this year’s Man Booker Prize. (‘It better not win,’ said a non-comics reader friend of mine upon hearing this. Luckily for them, it didn’t make the shortlist.) Sabrina is about a woman whose sudden disappearance triggers media interest, conspiracies and online vigilantism, adding to the distress of those nearest to her. Teddy, the bereft boyfriend, foists himself on his old high school friend Calvin. Working in military surveillance, Calvin is exposed to increasingly unhinged public guesswork about Sabrina’s fate. The regularity with which Calvin’s job requires him to fill out psychiatric self-evaluation forms – making clear his growing depression – divides the story, and maintains suspense. In the background, Sabrina’s sister Sandra has a breakdown. Most of the scenes occur in the dead hours between midnight and dawn, either in murky shadow, under bilious lighting, or in pitch black with neon linework. (The latter resembles the visualisations of sensory deprivation in Joseph Lambert’s Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller, from 2012).

As numerous reviewers have pointed out, Sabrina bears a striking resemblance to the work of Chris Ware, one of a handful of artsy comics-makers with whom bookstore regulars might be familiar. (Ware, incidentally, gave Sabrina a glowing review in the Guardian.) The likeness falls just short of uncanny – Drnaso is less rigidly confined to certain angles and perspectives than Ware and his characters’ body language isn’t universally downcast. But alongside all the big scope and grinding dystopianism, the similarities with Ware suggest that with Sabrina, Drnaso set out to make a consummate graphic novel. As Greg Hunter writes in the Los Angeles Review of Books, an ‘uncharitable take’ on Sabrina would see it as an ‘eminently – even excessively – adult and respectable approach to comics fiction’.

In interviews, Drnaso insists he’s ‘not insisting that [comics] deserve some larger place in the culture’ and said he thinks Sabrina didn’t deserve to win the Booker. He cancelled the book’s publication for a month after finishing the first draft in April 2017, because in his words,

it was way too negative. […] when it was all said and done, you know, Trump’s president and everything just seems evil and negative and awful and I thought: I don’t want to put another evil, awful thing into the world. At least, that was my perception of it at the time.

Nevertheless, reviewers have roundly praised Drnaso for taking on such seismic, ‘timely’ themes as surveillance, fake news, domestic terrorism and cultural amnesia. That an ambitious comic can still be treated like a novelty in this way might irk comics insiders. Don’t they know that comics have dealt with big issues since their grotesque realist origins in the nineteenth century? Don’t they know that even the dullest newspaper strips highlight the Beckettian drudgery and isolation of American domesticity? Don’t they know the entire history of my obscure little medium?

But the reviewers have a point. Cartoonists have obviously dealt with pressing issues prior to Sabrina. (Mary Leunig frequently does so, all at once, within a single gut-wrenching panel.) But none have really done so with such neatness and aplomb over a book-length work. And while Sabrina solidifies the sad-sack image of graphic novels, it does so in a style that stretches the limits of what the public normally find palatable in such comics. Sabrina then hints at the innovations and low-key revolutions occurring just outside the spotlight, in what has sometimes been termed art comics.

Style is at once Sabrina’s most familiar and experimental aspect: familiar insofar as it mimics the awkward immediacy of public infographics; experimental inasmuch as it pinches these familiar bits in ways that won’t totally put off non-comics readers. Drnaso’s drawings (clean digital lines, flat ashen palette, boxy shapes, blimpy physiques) resemble those in an airplane safety manual or a clinic waiting room pamphlet, the simplicity of which is more queasy-making than reassuring. They reflect an anaesthetized society, kept afloat and light-headed by pharmaceutical dependency and fishbowl routine. (Every bit of furniture in Sabrina looks like an ornamental aquarium treasure-chest.) Impeccably detailed panels somehow feel empty, because they’re too precisely cluttered.

Usually, minimalism of this sort leaves the reader to fill in the gaps, to provide the ‘beholder’s share’. This is the principle upon which comics, being fundamentally abbreviated, are supposed to work: their visual ellipses make for a mutable, participatory and mutualistic interaction between reader, artist and artwork. An aspect of this dynamic often overlooked by comics theorists is that the omission of details for the sake of efficiency means there is an underlying, perpetual sense of information withheld; that, as Scott Bukatman puts it, ‘neither the objects nor the space are fully “knowable”’. Drnaso pushes this opaqueness. His flat, eerily vacant drawings both demand and resist imagination, and make Sabrina’s absence felt more keenly. The characters in general are built around a kind of face-blindness. Their expressions, wavering in panel after panel between subliminal reaction and reticence, feel like they are drawn from the point of view of someone wading through an amnesiac fog, glimpsing vaguely familiar figures. Glimmers of emotion, such as tiny differences in the curve of someone’s lips, call for attention. Close-ups are especially jarring, because nothing much is revealed; only more of the same button-eyed blankness normally found in teddy bears and great white sharks.

As a result, expressiveness is sublimated into the background, where any hint of depth seems meaningful: for example, when Calvin, cornered by the press outside his garage door, accidentally refers to Sabrina as Sandra, and his shadow stretches to emphasise the aberration and its consequences; or more subtly, when the shadow cast beatifically by two bushes on a fence downplays the start of an abyssal point in Calvin and Teddy’s relationship.

Used more thriftly, this deadpan might feel calculated. Instead, Drnaso’s dedication to it pairs awkwardly and endearingly with its very indifference. Depictions of grief – which make up a fair amount of the book – are made stark, sometimes abjectly funny. Basic comics literacy leads you to expect lines, borders and text to shudder and bend along with big emotions, as when Teddy stands near-naked in the corner of his room screaming from night terrors, or when Sandra crumples on the floor howling and cradled by her friend Anna. But the style stays stony, encircling these outpourings.

Consequently, space in Sabrina is just that: space, a vacuum; at once boxed-in (cubicles, diner booths) and agoraphobic (featureless landscapes); both excessive and forbidden, ascetic, like the scale of private property envisioned by certain fascist regimes.

What this yields is an inverted form of social realism that deals not in gritty refuse but rather sterility and homogeneity. If, as popular culture would have us believe, American vastness used to compel a pioneering spirit, Sabrina depicts that as now ingrown; whereas the turn of the last century was marked by fears that too much was happening (culminating in pseudo-scientific ailments like neurasthenia), Sabrina presents a vision in which too much of nothing is happening. This makes palpable the hollowness left by both Sabrina’s disappearance and the banality of the lives upended by it. Drnaso’s insistence on methodically capturing – increment by tedious increment – the minutiae of people shuffling around, getting coffee and talking in a clipped, semi-naturalistic way, leans heavily into pathos, but evokes well the sense of these characters being under constant surveillance.

This pacing also takes its cue from certain video games. It captures the frustration of being stuck at a certain point in an over-plotted point-and-click problem-solver, when the story has shuddered to a halt because of either your ineptitude or bad game design, and you keep visiting the same locales looking for clues that might kickstart it. In these instances, the haunted, dead-end qualities of game aesthetics rear up: when you comb through a setting but keep hitting unseen boundaries, or enter a room for the third or fourth time, in which there’s a character repeating the same plot point indefinitely. The trajectory of Calvin’s moods, as shown by his psychiatric self-evaluations, resembles that of a video game protagonist whose health is constantly being depleted and briefly rejuvenated. The similarity is at its most literal when Calvin is seen playing Call of Duty. Isn’t it telling, Drnaso seems to be saying, that someone employed by the military in a desk-job capacity would live out warzone atrocities vicariously through gaming. (In this light, the blankness afflicting Drnaso’s characters resembles the sedated ‘computer face’ we assume when interacting with screens.)

That all this might amount to Drnaso declaring, ‘this is how we got here’ – here being Trump – is too easy a takeaway from a book that limits blatant political commentary, for the most part, to an unseen radio host character who is clearly an Alex Jones parody, and whose extended rants are easy to tune out, even while they’re radicalising Teddy. Just as swastikas never appear in Jason Lutes’ recently completed Berlin trilogy (2018), which depicts life in pre-second world war Germany, so Drnaso never once names Trump. This is because, on one hand, Trump’s presence, like Sabrina’s, is made palpable by its absence, and on the other, because the purpose of Sabrina is less to place blame than to demonstrate an understated but nevertheless radical form of empathy.

Drnaso’s work extends an older tradition of cartooning associated with artists like Otto Soglow, Crockett Johnson and Ogden Whitney, whose bone-dry, algebraic drawings act as straight man to empathic, melancholy storytelling. But whereas those cartoonists used banality for modest means (deadpanning jokes), Drnaso’s minimalism stands in stark contrast to the scope of his themes.

Chris Ware is the most famous current example of this anti-expressionistic style. Less well-known but more wildly imaginative is the Belgian cartoonist Oliver Schrauwen, whose masterpiece Arsène Schrauwen (2014), a magic-realist biography of his grandfather, ranks easily among the best that both art comics and graphic novels have to offer. (A belated modernist classic, Arsène Schrauwen found little reach beyond the art comics sub-sub-sub-culture upon its release.)

Another recent example is Anna Haifisch, whom Drnaso claims, in an interview for the Comics Journal, he would have considered emulating, had he more versatility as an artist. Haifisch’s newest book, Von Spatz (2018) – about an artist’s rehabilitation retreat where Walt Disney meets fellow cartoonists Tomi Ungerer and Saul Steinberg, and they participate in each other’s creative processes – resembles Sabrina in its minimalism, but differs in its warmth, vibrancy and impeccable comedic timing. (Despite all his characters seeming on the verge of smiling, the closest Drnaso comes to outright comedy is when Calvin surprises Teddy by appearing in a sleeved blanket.)

Schrauwen and Haifisch, like Drnaso, aim to unsettle with ambivalence. In the manner of Astro Boy creator Osamu Tezuka or a commedia dell’arte troupe, Haifisch builds her casts from a prefab set of figures with mask-like countenances; Schrauwen’s characters frequently lack faces altogether. Unlike Drnaso, Haifisch and Schrauwen inflect their drawings with tiny, hand-crafted flaws. This is one affectation common among art comics. The bullishness and sheer attitude with which Drnaso, Schrauwen and Haifisch foreground and stick to the weirder aspects of their styles – in Drnaso’s case, bloodless hues, reticent space, mannequin body language – is another affectation they get from art comics, where, at its most extreme, it can come across as posed and haughty, an old punk tactic for keeping non-punks at bay. But this belies art comics’ cornucopian variety, ingenuity and egalitarianism.

At first glance, the term art comics seems as unhelpfully vague as graphic novel. The two don’t necessarily exclude each other. Technically, the former is something like an ethos, while the latter merely describes a work hefty enough to be considered a proper book, as opposed to, say, a zine. But there is something about the connotations of the term art comics, antithetical to those of the graphic novel, which makes works like Sabrina or Arsené Schrauwen or Von Spatz, which further muddy these already murky definitions, worth a look.

Some ideas about art comics can be gleaned from listing their progenitors and outlets: the Hairy Who and the Chicago Imagists (RJ Casey’s review of Sabrina for the Comics Journal suggests Roger Brown, one of the key Imagists, as an influence on Drnaso’s style); 1960s and 70s underground comix; Gary Panter, whose long career includes designing the set for Pee-Wee’s Playhouse and, more recently, making lush, oversized comics adaptations of Dante and Milton; Art Spiegelman and Francois Mouly’s experimental comics magazine Raw (1980-1991); the Japanese monthly avant-garde manga anthology Garo (1964-2002); Providence, Rhode Island-based art collective Fort Thunder (1995-2001); Sammy Harkham’s sporadic anthology Kramer’s Ergot (2000 – ongoing); and most recently, the Latvian-based international anthology Kus (2007 – ongoing). Otherwise, art comics doesn’t describe any geographically specific or online scene, movement or unifying aesthetic, so much as certain qualities that emphasise (but aren’t limited to) experimentalism, iconoclasm, handmade production values and positive amateurism (to borrow a term from Sydney-based radical feminist art collective Dexter Fletcher).

The art comics label is accurate inasmuch as such comics take the fact that they are art as a given, rather than insisting on it, as opposed to literary comics, which have a Gen X fetish for authenticity. For the most part, the graphic novel’s old guard – Art Spiegelman, Charles Burns, Jaime Hernandez, Daniel Clowes, Seth – are retro-retentives who, for all their accomplishments, couch innovation in nostalgia and self-conscious allusions to comics history. (This seems to be a peculiarly male affliction; prominent women in the milieu, such as Julie Doucet, Marjane Satrapi, Lynda Barry and Alison Bechdel haven’t found it necessary to nod to the past quite so frequently.) By comparison, Sabrina’s canniness – its sense of being too plugged into the zeitgeist – is preferable, because at least it’s a current zeitgeist.

Art comics de-emphasize physical and thematic scale. Some of the best art comics are lo-fi zines that look like they were photocopied at Officeworks or a local library (Real Rap by Beatrix Urkowitz, 2013), or begin as modest online formal experiments before being collected in book form (Infomaniacs by Matthew Thurber, 2013; Well Come by Erik Nebel, 2014). Others repurpose outdated, idiosyncratic technology (risographs, gocco printers) in ways that maximise their variability, coaxing out the individuality of mass-produced objects.

Sabrina’s ambition may seem at odds with this sensibility. But the manner in which Drnaso goes about realising that ambition, aside from doing so in a hefty, long-form work, is otherwise understated. Rather than building on and adding flourishes to Ware’s model, Drnaso deconstructs it. He has no choice: by his own admission, he lacks the skill and flexibility necessary to be a ‘virtuosic artist’. It is these limitations that point to one of the most appealing aspect of art comics – specifically, that they downplay brazen drawing ability in favour of more eclectic, attainable forms of craftsmanship: loose charm (Tara Booth), folkish patterning (Mark Beyer), jauntiness (Urkowitz, Wakana Yamazaki), clutter (Jordan Speer), freneticism (Lale Westvind), casual absurdism (Thurber, Marc Pearson), glutinousness (Michael Hawkins), hard precision (José Quintanar, Tim Hensley, Yuichi Yokoyama) and sheer individualism (Josephine Edwards, Nicky Minus). This heterogeneity means that for all the highbrow cliquishness implied by the label, art comics are more in tune with the scummier, lumpen, scratched-into-a-classroom-desk, anarchistic aspects of their medium than most card-carrying graphic novels.

Art comics’ emphasis on visual ingenuity means they do often trade clarity and conventional notions of readability for good looks. This is also because their makers often arrive at comics in adulthood from other artistic disciplines without inbuilt knowledge of comics storytelling and its quirks. The timidity with pacing that afflicts many comics – an inability to trust, on one hand, the capacity for negative space to depict variable amounts of time passing, and on the other, that the reader will interpret these gaps accordingly – could be attributed to these late-comers, except that graphic novelists with presumably more thorough knowledge of comics history do it too. Its result is a tendency towards stodgy, incrementally paced sequences of someone doing relatable things like washing dishes, tying shoe-laces and putting hands to their foreheads in exasperation, that come off as too-literal interpretations of the old creative writing adage that more humdrum detail means greater engagement. Drnaso occasionally falls into this trap, perhaps because he is one such late-comer to comics; in a piece on Sabrina for the Guardian by Rachel Cooke, Drnaso points out that for all that he admires Ware, Sabrina is more influenced by TV and film. Cooke confirms that ‘reading Sabrina is an experience akin to watching a movie.’

Comics purists might balk at this. Why are comics still being likened to movies? Comics don’t need comparisons with other media to validate them as art! This only undermines their autonomy and distracts from their unique formal attributes! Nativism and essentialism of this sort manifests in polemics like R.C. Harvey’s “The Perversion of the Graphic Novel and its Refinement”, in which the author complains that ‘the shelves of the nation’s bookstores have been increasingly polluted with the works of ambitious well-meaning comics enthusiasts who don’t understand the medium and whose perversions of it not only threaten the form but indoctrinate an audience with false perceptions’.

Even if this were true, such criticisms can be levelled at any other medium. In ‘Is There a Cure for Film Criticism?’ (1962), Pauline Kael counters similar arguments put forward by fusty types like Siegfried Kracauer:

What motion picture art shares with other arts is perhaps even more important than what it may, or may not, have exclusively. Those who look for the differentiating, defining “essence” generally overlook the main body of film and stage material and techniques which are very much the same.

This is especially apparent in comics, whose essence is in fact their non-essentialism, their mutability and mimetic ability with regards to other media. In the past this may have damned them to the status of a hybrid, pre-literate, mongrel medium, but as the innovations going on in art comics show, it’s also one of their best qualities. Sabrina is a case in point: it resembles film, TV and video games, but is also undoubtedly a comic, one which reaffirms the aspiration of graphic novels towards class mobility on one hand, and points to the incoming generation of strident, self-assuredly arty pioneers on the other.

Sabrina’s ends on an almost imperceptibly optimistic note. The last page depicts Sabrina herself riding a bike through parkland. The image is infinitesimally more detailed and warmer than those preceding, like an extremity numbed by pins-and-needles through which blood is slowly re-circulating. Whether what we are seeing is taking place in the past, in some kind of afterlife, or in a present where Sabrina is somehow alive (a call-back to one of the many conspiracy theories described earlier in the story) is left ambiguous. It’s filmic in the sense that it resembles the shrewd but also tacked-on twist in an American Beauty-era Oscar hopeful. But in a comics sense it’s more understatedly clever, because it speaks to the medium’s innate ability to depict past, present and future simultaneously.

Works Cited

E.H. Gombrich quoted by David Kunzle, Father of the Comic Strip: Rodolphe Töpffer, Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Press, 2007, p.116-117.

Scott Bukatman, The Poetics of Slumberland: Animated Spirits and the Animating Spirit, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012, p.69, 83.

Kevin Huizenga, How to Start to Think About Learning to Draw Comics, White River Junction, VT: Center for Cartoon Studies, 2005.

Pauline Kael, “Is There a Cure for Film Criticism?”, in I Lost it at the Movies: Film Writings 1954 to 1965, New York; London: Marion Boyars, 2012, p.176.

Lost it at the Movies: Film Writings 1954 to 1965, New York; London: Marion Boyars, 2012, p.176.