Kim Scott’s fifth novel, Taboo, is an extraordinary testament to the new energies in Aboriginal storytelling that have emerged since the 1990s, the decade the Mabo decision overturned the legal fiction of terra nullius and recognised Aboriginal land claims in Australian law for the first time. As Scott said in 2012: ‘This is an Aboriginal nation, you know. It’s black country, the continent. Some people are starting to think about: can we graft a contemporary Australian community onto its Indigenous roots?’

Scott is a descendant of the Noongar people who first created human society along the south coast of Western Australia, around today’s Albany. It is this Noongar country – this particular, active, living land and its complex relations with beings human and otherwise – that Scott has been writing into the novel since his second book, Benang: From the heart (1999). Or, more accurately, since Benang Scott has been grafting the novel, this exotic literary form, onto his ancient Noongar storytelling roots, which are grounded in place. Scott is now a celebrated writer and author of five novels published around the world. In 2000 with Benang he became the first Aboriginal writer to win Australia’s most prestigious literary prize, the Miles Franklin Award, which he won again with That Deadman Dance in 2011.

Taboo is Scott’s most candid and generous novel yet. Set in the messy, violent and vital present of his Noongar country, it is also his most astonishing act of verbal conjuring. It opens with a communal statement about a ‘massacre place’ from voices that rise from the riverbed ‘as if we were the undead’, before hurtling into a contemporary story about a child, Tilly, lost to her people and returned to them and to her country (this same massacre place) by her Noongar father Jim Coolman. Except that Jim’s been imprisoned for violence against Tilly’s mother and dies before he can return her himself. So he enlists the help of his cousin Gerald, a sometime-fellow inmate who shares Jim’s passion for reviving their ancient Noongar tongue.

The opening literally races with the speed of a runaway truck; the narrators insist on this:

We thought to tell a story with such momentum; a truck careering down a hillside, thunder in a rocky riverbed, a skeleton tumbling to the ground. There must be at least one brave and resilient character at its centre (one of us), and the story will speak of magic in an empirical age; of how our dead will return, transformed, to support us again and from within.

The dead do indeed return, in countless ways, including as the ‘undead’ Noongar ancestors who rise from the riverbed to narrate the novel, their omniscient point of view sometimes focalised through key characters, notably Dan, Gerald, Tilly and Doug. Most movingly, the dead return as the tumbling skeleton invoked in this passage. The novel works then to tease out the mystery of the three figures who emerge from the truck after it has raced through the main street of ‘this little town in Western Australia’s Great Southern: Kepalup’, leapt off the bitumen and overturned in deep sand.

The first figure to emerge is a strong young woman, Jim’s daughter, who will carry the story. Then comes a much older man, then something like a skeleton. This creature is made from the stuff of Noongar country, from bones, polished timber, stones, woven grass, bright feathers, sinew, fishing line, possibly human hair and even fencing wire. The novel both suggests how this skeleton is reconstituted and brought to life by Noongar magic; and brings this being – and the Noongar country and people it is born from – to life, with words. The magician responsible for this creature, Wilfred, is the old man who rises from the truck. Not surprisingly, he is figured as a conjurer. At his touch, his pink and grey cloth sprouts wings and becomes a galah, then is cloth again. And he was once drawn by Noongar teacher Kathy ‘as some sort of magical or spirit creature, playful and erratic. It no longer seemed a caricature’.

Scott’s novels have always featured shape shifters like this, playful spirits or artist types who wrestle with the transformative magic of words and voicing, and their connection to place. In True Country (1993) Billy Storey starts recording the old people’s stories in a small settlement in Australia’s far north. The stories make him leap for joy: he feels himself ‘ascending into the stratosphere like one of those paintings of the Ascension’. In Benang Harley’s gift for song and stories – for conducting the many sounds of his country – allows him to hover over his land with the power of vision. That Deadman Dance’s Bobby Wabalanginy learns to write, keeps a journal, and can sing and dance the spirit of his place. His friend Dr Cross calls him a ‘gifted artiste’. Scott himself is a shamanistic sort of writer who inhabits the living and the dead, black and white, past and present, bringing them to life on the page and breaking down the boundaries between them.

As with all Scott’s novels, Taboo is about the alchemical power of words. It is words that allow Wilfred to make a squawking galah from a cloth, as he explains to his Noongar family gathered around a fire: ‘Words, see. It’s language brings things properly alive. Got power of their own, words. Some more than others. You’ll see, you’ll see proof soon enough.’ And sure enough, the novel does indeed show us proof. We’re given a clue to the nature of this magic when the fire explodes and ‘something jumped out of sparks and coals; eyes, a beak, smouldering feathers, long legs ran from the fire’. Wilfred names it, using the old word for curlew, their totem: ‘Wirlo, you might pick him up, think he’s just another bit of firewood!’ Wilfred says they might make something like that: ‘Something that jumps up from a pile of sticks. Life not just in us, you know. Not just flesh and bone, but something sparks us. Call it spirit.’ Another clue is given when we are told immediately after that ‘Flame licked Tilly’s piece of timber. She stayed long enough to watch its transformation. Dead timber coming alive.’

Here as everywhere in this richly poetic novel, the language is doing enormous work, telling many stories of reclamation and revival, including the actual story of a six-day journey back to country to recreate the land and bring healing; the story of Tilly, her father Jim and her Noongar roots; the more subtle, arcane story of the skeleton; and the story of the massacre place itself, now called Kokanarup, and its renewal by both its traditional owners and its present day owners Dan, Janet and Malcolm Horton.

The plot is driven by two events: the opening of a ‘Peace Park’ to commemorate the massacre and a Noongar workshop on this ancestral land. The organisers of the Peace Park, the Kepalup Local Historical Society, hope that the traditional owners might make some art or performance during their ‘culture camp’ as part of the opening. Dan Horton’s wife Janet, whom he can sometimes see despite her recent death, was involved with the Peace Park. As well as becoming a conservationist late in life and replanting thousands of trees on their desiccated land, Janet fostered Aboriginal children alongside their own son Doug, visited Jim Coolman in prison and wanted to work with the land’s traditional custodians to heal its violent past.

Dan’s ancestor William Horton sparked the violence in 1881 when he broke Noongar law by raping a woman and was executed by her family. The settlers retaliated with guns and poison. According to Gerald, Jim told him to get in touch with the Hortons, said they were alright, ‘can’t blame ’em for what their old people did’. And so Gerald and his identical twin brother Gerrard take Tilly back to Kokanarup before they join the Noongar camp on the coast at nearby Hopetown. This camp is enormously significant, as blind elder Nita – who can ‘see’, as her Cyclops-visor sunglasses suggest – makes clear:

‘This trip … well, lot of us never been back to this area, not our parents and grandparents even, not since the killing. The old people been waiting for us I reckon. I hope they’re not disappointed. We’re all Noongars here. Wirlomin Noongar.’

This Wirlomin clan is Tilly’s (and Scott’s) family, named for the curlew, wirlo. They belong to the country that opens the novel: ‘Our hometown was a massacre place. People called it taboo.’ Benang was also concerned with this place and the taboo that has hung over it for more than a century. Its first epigraph is an extract from Paul Seaman’s 1984 Aboriginal Land Enquiry, which mentions the massacre at Cocanarup, near today’s Ravensthorpe:

Many Nyungars today speak with deep feeling about this wild, windswept country. They tell stories about the old folk they lost in the massacre and recall how their mothers warned them to stay out of that area.

If Benang circles around this massacre, this taboo, Taboo confronts it head on – or heart on, perhaps – exploding and diffusing its power to keep these contemporary Noongars from their land, and telling the truth of this shared past. The title is telling. The word taboo is loaded with the British colonial endeavour, having been first used in English by Captain James Cook, appropriated from the Tongan. Meaning both sacred and unclean or cursed, and therefore prohibited, it implies an acculturated silence. The novel raises many other taboos harboured by White Australia, such as Dan and Malcolm’s reluctance to call the slaughter a massacre (instead they quibble over numbers and the historical record) – and by extension the reluctance of the nation more generally to name, own and reckon with this bloody past. Other taboos the novel voices include the fact that having been dispossessed from their ancestral land, had their language crushed, and bodies and spirits violated, the people who created the first societies on this continent and flourished here for some 60,000 years (an ever-increasing estimate) now struggle to find a place here; the fact that they are plagued by introduced spirits like alcohol and drugs; that many of the men die young and spend time in prison for violence, especially against women; that children born of violence are often fostered out and may in turn be violated. Old acts of violence reverberate down the generations. Taboo mentions the policies offered up by governments to address these tragedies, such as ‘Closing the Gap’ and ‘Reconciliation’, suggesting the first is empty rhetoric and the latter doesn’t get to the heart of the problem. Wilfred and others talk of ‘real reconciliation’: not just acknowledging and being sorry for stolen land, but returning that land to its rightful owners. This is the nation’s greatest taboo.

To this charged material Scott brings the lightest of touches. Gone are the rage and intellectual pyrotechnics that fuelled Benang’s story of the Stolen Generations; gone is the need to position Noongar confidence, spiritedness and inclusiveness at the earliest moment of contact with European settlers, as in That Deadman Dance. Instead, Taboo reconstitutes this rich Noongar spirit in the present day and brings it directly to bear on the traumatic past and violent present, bringing life and healing to both. This healing is made possible by the recovery and return of the old Noongar language and stories of this place.

After writing Benang, Scott met Noongar elder Hazel Brown, who helped him to connect to his country and ancestral language. In 2007, when reflecting on the theme of postcolonialism and globalisation for Meanjin, Scott drew on this immersion in country and language to stress the continuing significance of regional Aboriginal cultures in a globalised world. Noting the relatively new interest of mainstream Australia in Indigenous culture, notable during the 2000 Sydney Olympics, Scott spoke of the different stories that can be told of Indigenous Australia: the ‘preferred’ imagery of an ancient and continuing culture, of traditional practices and a remote and exotic ‘other’; the story of the continuing legacy of oppression, racism and injustice, focused on loss and dispossession from country, language and family; or a third story, one of reconnection:

Such a narrative would tell of the struggle to reconnect individuals and small groups of people to one another, and to a sense of history and heritage derived from a specific place. Indigenous language is an important part of this, and for someone in my position that means the revival and regeneration of an ancestral language.

This third story is the one Scott is living and writing. His work with Brown and his Noongar heritage led to Kayang and Me (2005), the family memoir they wrote together which connected oral history and archival material. Their collaboration coincided with the return of a remarkable cache of Wirlomin stories recorded by American linguist Gerhardt Laves in Albany around 1931. After Laves’ death his papers eventually made their way to the University of Western Australia, where Scott and members of the Wirlomin family first saw them in 2002. Many of the old people Brown had mentioned had spoken to Laves some seventy years earlier and their stories had miraculously returned in Laves’ papers. So Scott, Brown and some relatives decided to invite a group of their descendants and others from the Noongar community to a workshop to share these freshly recovered stories. About fifty people turned up and within ten minutes they were all crying. Scott said at the time that the workshops were:

using stories to bring people together and to share a heritage and consolidate who we are as individuals and as a group, and from that centre widening the circles to include more and more people in it …

To reclaim these stories and dialect properly and share them with Noongar families and communities, Scott helped to found the Wirlomin Noongar Language and Stories Project (Wirlomin Project). It’s become a fundamental part of his work as a writer and feeds into his novels, just as his ‘literary stuff’ is about arousing interest in his language work, as he explained to Anne Brewster after the publication of That Deadman Dance. Through this process of cross-fertilisation, he is creating ‘a sort of cultural literacy, so that I can have references through the novels to this other work’, as he did with That Deadman Dance.

In 2011 the Wirlomin Project published its first bilingual picture books, Mamang and Noongar Mambara Bakitj. Mamang is about a young boy who dives into a whale’s spout, pokes its heart and sings a whale song. The whale dives deep and travels through the ocean. The boy eventually beaches the whale, climbs out and sees two women. He’s brought them riches: a whale. He returns home a wise and wealthy man. In the opening pages of That Deadman Dance Bobby begins to recall this story and it infuses the novel. It also echoes through Taboo. The semitrailer in the opening scene is figured as a whale: the truck, driver and passenger ‘make a wailing chorus’ (That Deadman Dance plays with the homophony of ‘wail’ and ‘whale’; its working title was ‘arose a wail’); when the truck is finally slowed by sand it makes ‘one last, dramatic gesture (reminding one observer of a feebly breeching whale)’; and it is later described as ‘an old and bulbous truck’, ‘its bonnet lifted above a dark and dusty maw’. The semitrailer spills forth great wealth and its passenger is golden, uplifted, triumphant in homecoming.

This is typical of the many resonances that charge through Taboo as it draws on and revives old Noongar stories. The story is continually interrupted to comment on how it is being told, on what it is and is not, drawing attention to its own telling as Scott’s novels tend to do. And within the novel many stories are told. At one stage during the camp Gerald starts a story that is taken up by Kathy. But Tilly can’t make sense of it and interrupts.

It was almost like a children’s story that began, ‘Once upon a time …’

Anyway, there was a young man …

‘Can we make it a woman?’ Tilly interrupted, surprising even herself.

Kathy paused.

‘You’re right, this woman …

She was polite and curious, this girl, this young woman in the story and really it comes down to this: she trusted herself and her instincts, and found and followed some barely detectable trail that no one else could even see …

This is the story of Noongar Mambara Bakitj, retold by Kathy with a young woman as protagonist instead of a young man, within a novel that acts to retell this same story in its own contemporary way.

In the spirit of Scott’s ancestors who appropriated the songs, language and cultural forms of the European newcomers, Taboo also co-opts the tropes of western fairy and folk tales. It repeats the word ‘fairytale’ itself as well as its traditional opening ‘Once upon a time’; and features goblins, dolls, puppets, doppelgangers, ‘the Tin Man from Dorothy’s Kansas’, a Gollum, Cyclops and Dracula. But despite this, the narrators also tell us early on that it ‘is no fairy tale, it is drawn from real life’. And so it is.

Once the Wirlomin Project has given the stories back to their Wirlomin descendants and community, they are then shared with wider and wider circles of people in an ongoing process. Scott has described this process of sharing as surprisingly empowering and ‘almost transformative’. As an example of this, in a recent essay he recounts his experience of taking a story back to the massacre place with a group of Noongar relatives. They were invited onto the property by two old rural brothers. ‘We thought ourselves intrepid to be returning to the region with the stories and sounds of ancestors, but had not anticipated being invited onto the property itself.’ Of this surprising turn Scott says:

The elders in our group had not thought they would ever return, even temporarily, to this particular area of ancestral country in their lifetimes – let alone with its stories and language – and to be acknowledged in this way.

This story also feeds into Taboo. The first individual human the narrators name is one such white man: ‘We remember Dan Horton. He will seem a stereotype, even a caricature, this stooped and elderly man’. Dan is ‘one of those rural men’ who will suddenly crouch in the middle of conversation and draw diagrams in the dirt. We know this man. But over the course of the story, guided by his wife’s ghostly presence, his strong Christian faith, and his love for and connection to this same Noongar land, Dan extends this familiar rural figure with a series of exemplary acts.

Other white Australians are similarly acknowledged. As Gerald says at the workshop:

Wadjelas, all Australians, this is what they’re gunna want to know. Some of them do already, the good and clever ones. Blackfella stuff, it’s not just up north in the desert, it’s here and we’re the ones to be passing on how to really belong here …

But others are sent up for their ignorance of and tendency to commodify Aboriginal culture, such as the members of the Historical Society who request a Welcome to Country, a song, dance or art as part of the opening of the Peace Park, believing that Aboriginal cultural artefacts can be provided at will for white ceremonies. The elders agree to give them something, but maybe not what they’re expecting. Wilfred wants to give them something good, ‘like to sit ’em back in their socks’. The portrait Scott paints of the pompous so-called Aboriginal Support Officer, Maureen McGill, is very funny – and provocative. McGill thinks she knows more than her Aboriginal students do about their culture and blithely tells them so: ‘I’ve worked with lots of Aboriginal people, you know, up north. Cultural people, still on their country. I’ve got a skin name.’ But comedy can only go so far. The novel is ruthless with its most malevolent contemporary presence, its ‘dark star’, a white drug dealer who preys on the lost and dispossessed, trapping them in a spiral of drugs and violence. Gerald is managing to find a way out of this prison through the old language and stories. When he refuses a bong, he’s asked if he’s found Christianity and replies ‘Nah. Better than that.’ Other Noongars are not so grounded.

Although Taboo tells of the return of Noongar words and stories, most of the old language talk happens off the page. It’s conveyed only partially – fragments, conditional tenses, the hypothetical and ellipses abound – and in English, appropriately enough given the sacred spiritual connection of language to its place and people. Only four Noongar words appear on the page: wirlo, Kaya and Yoowarl koorl. Given the enormous weight Scott accords every word, it’s worth considering their significance. Wirlo, as mentioned, gives its name to the family whose ancestors were massacred and who now return to their country for the first time in over a century. Kaya is the only Noongar word Tilly speaks. It’s also the first word in That Deadman Dance, written by Bobby on a piece of slate. It means hello or yes. It’s a welcoming word, spoken with great authority by Bobby as one who is secure in his country and open to the culture of others. The phrase Yoowarl koorl, which sounds like ‘you are cool’, is spoken first by Jim Coolman when he greets Tilly, and again by his cousin Gerald Coolman. The phrase means ‘come here’. It calls up, conjures even.

As Gerald’s experience suggests, the old language is healing. Scott has spoken widely about the far-reaching significance of language reclamation for the health of Indigenous communities and for the health of Australia. He’s seen first-hand the benefits and improved social circumstances that come from reconnecting people with their pre-colonial cultural heritage, having worked in Indigenous health (he edited a textbook on the subject to enlighten non-Indigenous practitioners). It is a better way, Scott believes, than the prevailing ‘paradigm of resistance’. In his interview with Anne Brewster, he called this ‘the wrong narrative for Noongar people’. Instead, he prefers to assume their old gentleness and generosity of spirit, qualities freely remarked upon by the early invaders. In 1833 R.M. Lyons wrote in the Perth Gazette that the Noongars

not only abstained from all acts of hostility when we took possession; but showed us every kindness in their power. Though we were invaders of their country, and they had therefore a right to treat us as enemies […] these noble minded people shared with us their scanty and precarious meal; suffered us to rest for the night in their camp; and, in the morning, directed us on our way to headquarters, or to some other part of the settlement.

For Scott strengthening Indigenous communities is also the only way an Australian nation-state ‘will have any chance of grafting onto Indigenous roots’. He suggests this process is vital for the social, environmental and spiritual health of this continent. I think he is right. In their conversation following the publication of That Deadman Dance, Brewster asked Scott if a non-Indigenous person can be ‘accommodated by the spirit of the ancestors and the place’. He said: ‘I think they can. I wouldn’t want to move too quickly to that. I’m certainly signalling those sorts of things.’ If That Deadman Dance signalled such things, then Taboo begins to imagine them. As Scott said of his experience of being invited by the two brothers to the massacre place to share food and stories: ‘Who knows? Such things, humble as they are, may be the harbingers of social transformation.’

This year marks three important anniversaries: it’s fifty years since the 1967 Referendum made Aboriginal people count officially for the first time in modern Australia; twenty-five years since the Mabo decision of 1992; and twenty years since the publication of The Bringing Them Home report on the Stolen Generations. And yet we seem no closer to reconciliation today than we were before these landmark events. Indigenous struggles for justice, truth-telling and respect continue. In these turbulent times, words and stories are more important than ever. Scott is one of the most thoughtful, exciting and powerful storytellers of this continent today, with great courage and formidable narrative prowess – and Taboo is his most daring novel yet. It conjures a place – an awkward and uncomfortable emotional terrain – where Indigenous and settler Australians can come together. And it recognises all those who attempt genuine acts of reconciliation, who acknowledge that this continent is black country. It is above all a novel about return. May its voice, its Noongar spirit, travel far.

References

Anne Brewster, ‘“Can You Anchor a Shimmering Nation State via Regional Indigenous Roots?”: Kim Scott talks to Anne Brewster about That Deadman Dance’, Cultural Studies Review, 18.1 (2012).

Jane Kennedy, ‘Maman and Noongar Mambara Bakitj: Noongar stories keeping heritage strong’, ABC.net.au, 13 October 2011. Accessed July 2017.

Kim Scott, True Country, Fremantle Press, North Fremantle, 1993.

—Benang: From the heart 1999, Fremantle Press, North Fremantle, 1999.

—‘Covered up with sand’, Meanjin, 66.2 (2007).

—That Deadman Dance, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2010.

—‘Not so easy’, Griffith Review,47 (2015).

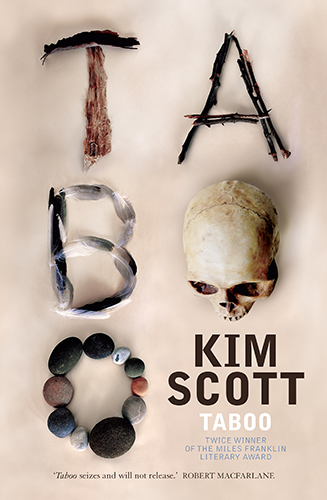

—Taboo, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2017.

Scott, Kim and Hazel Brown, Kayang and Me. Fremantle Press, Fremantle, 2005.

Alexander Turnbull Yarwood and Mike J. Knowling. Race Relations in Australia: A history. Methuen Australia, North Ryde 1982.