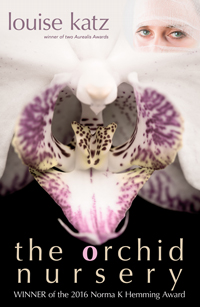

In The Orchid Nursery, Australian writer Louise Katz, winner of this year’s Norma K Hemming Award, creates a society where certain young women are chosen to undergo radical physical transformations in order to serve the desires of the patriarchy.

Once upon a time the topos of transformation might have been most familiar from Greek and Roman myths: tales such as the one about the beautiful maiden who is turned into a heifer, or the nymph who changes shape so as to thwart her divine pursuer. Imaginative and inventive stories like these reflected the dire and magnificent influence of forces beyond human understanding. They are sources for ravishing depictions of the process of becoming something other, for art makes possible the limning of the in-between. Take, for example, Antonio del Pollaiuolo’s Apollo and Daphne. Describing the painting Seamus Heaney writes:

the god appears like a bare-legged teenage sprinter who has just managed to lay his hands on the fleeing nymph. Myth requires her to take root on the spot and begin to sprout laurel leaves and branches, so her loosely robed left leg does appear to be grounded while two big encumbering bushes have sprung from stumps on her shoulders.

These myths of bodily metamorphosis are the main focus of Ovid’s great poem about change, but it is interesting to note that it is most often the bodies of his female characters that are sexualised and exploited.

In continuity with this tradition, Katz envisages a not-so-distant future where women are offered up as sacrifices, extrapolating from the kinds of procedures willingly undertaken in the quest for perfectibility, as well as the horrors of genital mutilation.

The dystopia she has created is the ironically named State of Civilisation, a place where Christlam, the Dual True Faith, rules. Here, female initiates unreflectively utter the apotropaic prayer, ‘Blessed Be His Cock-and-Muscle, alive-alive-oh-oh ever amen’ (often rendered acronymically as BBHCM) and are indoctrinated into wanting to subject themselves to the ideologically derived atrocities that will be inflicted upon them in the name of God. Subjugated by religious texts taken from the Doppelbook (an amalgam of the Bible and the Qur’an) their objectification is complete.

Girlies, whose slave-like status is signalled by their lack of a true surname (reminding readers of Atwood’s Offred and Kathy H, from Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go), are cloistered in cunnydorms where they learn about Attracting the Gaze and Charming the Snake. They are taken to visit the Museum of Iniquities, and taught to recite the Tenets of the Ways of (wo)Man, the Sacrificial Path, and the Sins of the Child. Instructed in the ways of Sacricunt and Dutilove and tutored in the arts of Sating the Man, Sedating the Ego, and Stilling the Mind, these youngsters count off the years to their Attainment.

Reversing the Madonna/whore dichotomy, in this world the good woman is the one who is purely sexual, giving herself up to be scalpelled and sculpted into an embodiment of procreative function. Brainwashed, the girlies seek Perfection, longing to become womanidols, ‘unencumbered by superfluous foliage or limbs’. Ideal vessels for Seed-bearers, who press against the hourglass-shaped containers these women have become in order to ‘slip their cocks up and into the slots below’, these so-called ‘exemplars of femininity’ are all biological function, with no other life.

One of the blindly faithful, protagonist Mica earnestly believes that because ‘orchids live and grow in beauty and fecundity in secret places’ then ‘the greatest thing a girlie can do is to live that metaphor, to be the image, to live and serve and die in humility.’ In her acceptance of paternalistic domination she resembles many female protagonists from the dystopian tradition who are often guilty of complacency and complicity. In contrast, her closest friend Pearl is rebellious and irreverent (she says at one point, in keeping with her name, ‘I was aggravation. I was irritation.’). Questioning the pieties of the regime and subversively identifying herself ‘as defiant as the traitor who began it all . . . Lilith’, she falls for a man called Asa with whom she shares the forbidden pleasures of truly desired sex. Upon being informed that she’s been chosen for Perfection, Pearl decides to escape the ‘rules and restrictions and walls’, intending to meet her lover in ‘the nowhere, elsewhere and otherwhere’ of Unrule. In this place, as its name suggests, Civilisation holds no sway.

The easiest genre in which to categorise The Orchid Nursery is speculative fiction. But genre categories can be limiting, thereby condemning works of literature to languish on bookshop shelves or in warehouses somewhere never to be bought or read. Even categories as indeterminate as the speculative fiction genre seems to be.

That much ink has been spilt defining the genre of speculative fiction is not surprising given it encompasses fantasy, sci-fi and horror. Explanations range from the pithy – ‘whilst respecting Newtonian physics, authors writing speculative fiction extend scientific or social trends to extremes’ (Perry Glasser) – to the confusingly broad – it encompasses ‘a heterogenous group of contemporary socio-cultural perspectives from the most ‘realistic’ of SF novels to the most allegorical of experimental fictions’ (Veronica Hollinger).

When I was young, my reading was decidedly omnivorous and undiscerning. Unlike the exceptional few, I was a compliant reader, not yet active and self-aware. I brought my imagination and sympathy to the experience but little else. That’s why, in Year 9, I rated John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids, Chocky, and The Midwich Cuckoos more highly than The Day of the Triffids, which we’d yawned over in class. No doubt because I’d ‘discovered’ them for myself. Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, recommended by the life-changing librarian who worked at the tiny local library, came around the same time. As to where Patricia Wrightson’s An Older Kind of Magic and Alan Garner’s The Owl Service fit into this chronology, I have no idea. Nonetheless, I found the latter a particularly magical story that resonated with me not only because I am a child of the 60s but also because I’d spent lots of time at the Royal Crown Derby factory, where my father was the manager, watching, among other things, dinner plates, bowls and platters being removed from the hot mouths of kilns. I felt in possession of a sort of insider knowledge.

Like most Australian students, we studied the requisite dystopian texts: Huxley’s Brave New World, which I liked because it was short and the prose fairly easy to comprehend, and Nineteen Eighty-Four, which I found more difficult, skipping the section where Winston begins to read Goldstein’s book to Julia, who falls asleep. That the ‘Appendix: Principles of Newspeak’ was germane to Orwell’s message concerning language and the manipulations of people’s minds altogether escaped me so I never even opened those pages. I found myself horribly thrilled by Neville Shute’s On the Beach, the threat of nuclear war having become very real because we’d been shown Peter Watkins’s 1965 docudrama, The War Game, by a radical teacher who later disappeared from the classroom, her absence never explained despite our persistent questions.

In my early twenties I adopted an, at times, obdurate feminist stance regarding the books I read, but even though there were a few titles from The Women’s Press—I vaguely remember some names: Sandi Hall, Joanna Russ, Ellen Galford—and other like-minded publishing houses, that I’d loved, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper did nothing to induce me to read Herland, and nor did being enthralled by Monique Wittig’s L’Opoponax (in the English translation, of course) whet my appetite for Across the Acheron.

The decision to ignore novels like these was something like a reflex action; I simply wasn’t much interested in imaginative revisionings of what Hollinger refers to as ‘patriarchal things-as-they-are’. Or any other kind of fiction readily identifiable as being speculative.

The final straw came when, under duress, I read a volume from the Dune series in which one of the characters in Herbert’s waterless world was described, if I remember rightly, as riding a worm as a surfer rides a wave.

I was also deterred by the all too often lurid covers. For some reason, although Roger Dean’s hippy-trippy album art appealed to me, stylistically similar images on sci-fi, fantasy, and horror books definitely didn’t. The sheer heft of them put me off as well. Although, at the same time the books felt flimsy and, with pages prone to yellowing, seemed insubstantial. I was looking for something more permanent. That’s why I felt the glad rush of identification when I read Glasser’s humorous Letter to the Editor in which he asserts:

authors such as Margaret Atwood will resist being called ‘science fiction writers’ as long as the science fiction aisle continues to be home to whatever can be printed on cheap paper, bound with glue little better than spit, and expected to have a shelf life shorter than a can of beer.

There are readers who don’t want to buy such books as well.

A retrospective diagnosis of my reading habits might have it that I was suffering from ‘textism’, a form of readerly blindness deriving, as Marleen S Barr explains, from ‘a discriminatory evaluation system in which all literature relegated to a so-called sub-literary genre, regardless of its individual merits, is automatically defined as inferior, separate and unequal.’ I find Barr’s definition rather slippery; the phrase ‘regardless of its individual merits’ is an odd one in that it suggests that there’s such a thing as generic worthiness. What this might be, I find hard to envisage. Of course, textism is here used as a euphemism for snobbery, elitism, and narrow-mindedness; it’s a less-than-veiled accusation that people like myself consider themselves superior because we tend not to read commercial or genre fiction. How, then, to make sense of the pleasure I take in reading crime novels?

Some would have it that so successful has my inculturation been, I’m no longer conscious of how my literary tastes were formed – unlike Janice A Radway. She admits, in A Feeling for Books: The Book-of-the-Month Club, Literary Taste, and Middle Class Desire, that whilst ‘learning to describe the aesthetic complexities of true literature’ at university, ‘I tried hard to keep my taste for bestsellers, mysteries, cookbooks and popular nature books a secret—a secret from everyone, including the more cultured and educated self I was trying to become.’ Ursula K. LeGuin would simply say that I lack imagination and want only to live in the real world, reasons she proffers for adults not reading fantasy novels. But I indulge in the joys of escapism as much as the next person, perhaps even more so.

I suspect that what I’ve written so far runs the risk of sounding too much like a biblio-memoir and it’s a long way from what I originally promised the editor. Were I Geoff Dyer wrestling with this topic I might have turned this into a witty, meandering, deeply knowledgeable reflection on my failure to write what I said I would. As things stand, I can only tell you that as I set about re-opening my eyes to the genre of speculative fiction I found myself running into difficulties.

First up there was the bizarre experience of reading Damien Broderick’s chapter from the Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction in which he discusses Philip K. Dick, a writer he regards as ‘brilliantly iconoclastic’. Of what he acknowledges as being this writer’s ‘commercially-driven’ fiction Broderick has this to say:

but something wonderful happened when his hilariously demented tales ran out of control inside the awful covers of pulp paperbacks. Australian critic Bruce Gillespie has posed the central quandary, not just of Dick’s oeuvre but for sf as a maturing yet weirdly shocking paraliterature: ‘how can a writer of pulpy, even careless prose and melodramatic situations write books that have the power to move the reader, no matter how many times the works are re-read?’

Deftly side-stepping questions about the style of writing typical of the genre, Broderick continues:

part of his answer is that Dick repeatedly takes us on an ‘abrupt journey from a false reality to a real reality’ or, in the extreme case, ‘a roller coaster ride down and down, leaving behind normal reality and falling into a totally paranoid alternate reality. By the book’s end, there’s nothing trustworthy left in the world.’

This seems to me obfuscatory. And, as to what the rest of Gillespie’s answer might be, we’re never told.

Then I started to notice that because fantasy and sci-fi belong to the category of what Broderick calls ‘idea-centred fiction’ critics and academics seem predisposed to focus on themes, often at the expense of other aspects of the narrative. Sitting in the State Library surrounded by books and journal articles I read little that would compel reluctant or resistant readers like myself to seek out the novel or short story under discussion. The craft of storytelling rarely rated a mention, characters got short shrift, and much of what was written lacked any sense of passionate engagement with the texts.

Alongside this, when I did get round to trying to read them, too many of the narratives struck me as dull, their authors opting for a ‘dreary dun-coloured realism’ that seemed profoundly at odds with their intention to evoke characters in otherworldly or devastated settings whose identities and emotional lives are shaped by extreme social forces, by constraining and determining religious and cultural values. But there’s no accounting for taste, is there?

My research and reading confirmed what I’d suspected all along: most interesting texts don’t fall into easy categories. That’s why I wanted to turn my attention to Katz, a writer who understands the art of storytelling and revels in the expressive possibilities of language – but who risks being consigned to an aisle in a bookshop where few of us will venture because the marketing and selling of books demands that she be ascribed to a genre.

This novel exceeds the bounds of genre, playing, as it does in the manner of Angela Carter, with fairytales and the carnivalesque. Witness the episodes involving Mica’s encounters with the sexually indeterminate Grimalda Grace and her companion Motley, characters who provide her with a haven, in their ‘tottery house by the river’, from the vengeful Ecumen who patrol in blimps in the hope of capturing renegades and apostates. Whilst masquerading as Rangers who serve the regime, these two are actually smugglers and spies involved in subversive activities, such as counter-propaganda missions. Pearl is given work in their friend Mandrake’s studio writing stories about heroes, usually girls, ‘who are valorous beyond belief, optimistic and opportunistic and vulgar and mean and sweet’, which will be disseminated to the girlies disguised as acceptable spiritual material.

Running in parallel to these exuberant scenes are the ones involving the wicked and wise Hag who tends the wounds inflicted on Mica when she risks her life going in search of her missing friend. This eccentric, fiercely independent, witchy woman shelters the runaway in her Hagovel. A number of the longer chapters in the book are devoted to the tales she tells to her naïve interlocutor about life before the ironically named ‘War of Liberation’. Refusing to forget the past, the Hag’s stories allow the reader to evaluate the land of the Sacred Crescent and Crucifix against the late twentieth-century Sydney that’s been lost, a city that not only succumbed to riots and environmental disaster but was also taken over by pious American Christians and North African Muslims who have cannily joined forces in order to consolidate their power. The Hag tolerates Mica’s ‘simple-minded regurgitations of dogma [that] pass for thoughts’ and quietly admires the fact that she is brave ‘despite knowing only a life of submission’ and is grateful that ‘the overriding curiosity-switch still works.’ Unlike her precursor Offred, from The Handmaid’s Tale, who says, bitterly, ‘What I need is perspective’, Mica is given a new position from which to look at her world — but does she possess sufficient bravery and curiosity to overcome her indoctrination at the hands of Mother Oblation?

This is a novel with a frightening message, and one that explores confronting and hideous ideas that many of us fear are becoming all too tangible realities, but it is not only the struggles the characters face that engage the reader, equally important is the manner in which the story is told. The author has made a wise decision in using three equally interesting and sustained women’s voices that are interleaved to create the storyline. Not only are different viewpoints about the experience of living in and outside the dystopia explored but the resultant structure obliges us to be more actively involved in the story’s unfolding rather than passively consuming it.

Katz’s scholarly interest in the corruptions of language by bureaucracies and institutions under the influence of neo-liberalism is evident in The Orchid Nursery. The proliferation of capitalised words parodies authoritarian attitudes that give rise to sloganeering: for instance, in the opening pages Mica explains that ‘The Propaganders of Art & Pain, Yearning & Duty, of Instruction & Destruction, guide us within the blessed order established after the long, hard-won Liberation.’ Acronyms such as BBHCM, UMM (United Modesty Movement), and GEET (God’s Economic and Ecumenical Trust) reflect how jargon is used to consolidate a sense of insiderness whilst simultaneously emptying words of their meaning. Euphemistic language hides terrifying truths, an example being when Mica states, ‘the Spare Parts Manufactory [is] where the dudbubs live for a short while’, leaving the reader to imagine the uses to which these poor unfortunates are put. Most distinctive is the clever use of what are often tongue-tickling compounds—‘corp-yard’, ‘cunnydorm’, ‘cockslot’, ‘Sacricunt’, ‘Dutilove’, and ‘Pantastrophe’, words that have a lasting resonance because of their sounds and rhythms. Katz also slides and glides among registers in a manner that compels readers to think about the contradictions, hypocrisies, and bizarre ideologies that have given rise to an abominable dystopia overseen by a perverse regime.

Speaking at a Guardian Live book club event earlier this year, Don DeLillo, another uncategorisable writer, said, ‘My role as a writer is to create language … This is what the challenge is for me: language … the word, the sentence, the paragraph.’ Katz also sees this as her challenge, unlike the many who, rather than playing with the tropes and structures and character types recognisable from the genre of speculative fiction, are content to write books that are all too easy to pigeonhole. This is one of the main reasons, I assume, why they don’t get talked about in pages like these: we’re looking for writers who do think about the effect of every word, sentence, and paragraph.

Works Cited:

Marleen S Barr, ‘Textism—An Emancipation Proclamation’, PMLA (Vol. 119, No. 3, May 2004, pp.429-30)

Damien Broderick, ‘New Wave and Backwash: 1960-1980’, (eds.) Edward James, Farah Mendelsohn, Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction, (Cambridge University Press, 2003)

Tim Cook, ‘Don DeLillo on Underworld: ‘there was no escape’’, Guardian Review of Books (11th June 2016)

John Frow, ‘’Reproducibles, Rubrics and Everything You Need’: Genre Theory Today’, PMLA, Vol. 122, No. 5, Oct. 2007

Perry Glasser, ‘Letter to the Editor’, PMLA (Vol. 119, No. 5, Oct. 2004, p.1534)

Veronica Hollinger, ‘A New Alliance of Postmodernism and Feminist Speculative Fiction’, Science Fiction Studies (Vol. 20, No. 2, July 1993, pp.272-276)

Louise Katz, ‘Feeding Greedy Corpses: the rhetorical power of Corpspeak and Zombilingo in higher education, and suggested countermagics to foil the intentions of the living dead’, Borderlands e-journal (Vol. 15, No. 1, 2016, pp.1-26)

– The Orchid Nursery (Lacuna Publishing, 2015)

Jessica Johnson, ‘You May Also Like: Taste in an Age of Endless Choice’, The New Republic (9th June 2016)

LeGuin, Ursula K ‘Why Are Americans Afraid of Dragons?’, Susan Wood (ed.), The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction (Ultramarine Publishing, 1980)

Radway, Janice A, A Feeling for Books: The Book-of-the-Month Club, Literary Taste, and Middle Class Desire (University of North Carolina Press, 1997)