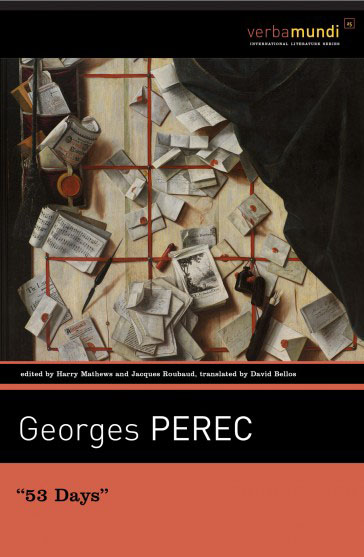

“53 Days” by Georges Perec: ‘C’est l’Australie qui m’a foutu mal!’

At the end of August 1981, Georges Perec, basking in the extraordinary success of his award-winning novel Life A Users Manual, touched down at Brisbane’s Eagle Farm airport. The French writer, filmmaker, OULIPO member and literary prankster was to spend one month as writer-in-residence in the French Department at the University of Queensland, followed by a three-week tour of the rest of Australia including Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide.

In total, he was excited to relate to his friends back home, he would be away from France for precisely 53 days – exactly the amount of time it had taken Stendahl to dictate The Charterhouse of Parma. Over the course of his Australian sojourn, he told them, he would himself produce a novel in 53 days – a detective story, involving the mysterious death of an author, as narrated by a man who is attempting to write a book in 53 days. It would be called “53 Days”.

It was never finished. Four months later Perec was dead. Before he died a student at the University of Queensland bumped into a haggard looking Perec in Paris. ‘C’est l’Australie qui m’a foutu mal!’ he said – Australia fucked me up. That story came to me via Colin Nettelbeck, now Emeritus Professor of Languages and Literature at the University of Melbourne. He is one of the many scholars who met Perec during his time in Australia with whom I corresponded as I wrote this essay.

While Malcolm Turnbull might claim that there has never been a more exciting time to be an Australian, those in the ‘intellectual sector’ who have seen their resources dwindle rapidly in the twenty-first century, might differ. The 70s and 80s were a genuinely exciting time in Australian academia. Well-funded and outward looking (culturally rather than financially, pace 2016), there was a real sense that Australia was building an intellectual culture that embraced internationalism. When I spoke to academics who helped bring Perec to Australia, there was a palpable sense of exhilaration at being part of a system that allowed them to engineer such visits – and despair at the position of Australian academics now.

Georges Perec is one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century. Born in 1936, he was the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland. His father was killed at Champigny fighting for the French army when Perec was four. His mother sent the young Georges to the country; she was deported to a concentration camp at Drancy. She survived there for nineteen days before being taken to Auschwitz and gassed. Perec was brought up by an uncle and aunt. He last saw his mother on the platform of the Gare de Lyon.

He came to prominence in 1965 when his first published novel Les Choses: Une Histoire des Années Soixante (translated into English in 1967 as Things: A Story of the Sixties) won the prestigious Prix Renadout. This novel introduced the techniques and themes that inform all of his work: the dazzling wordplay; the use of mirrors and mirrored texts; encyclopaedic descriptions of objects combined with non-psychological descriptions of people (people in Perec generally act rather than think – as he himself said of his novel writing process – ‘Feelings? You can put them in at the end’); and a fascination with using mathematical formulas to generate ideas.

Things was a huge success and immediately caught the attention of the semi-secret literary cabal OULIPO. OULIPO is an acronym of the French phrase Ouvroir de littérature potentielle, meaning ‘workshop of potential literature’. Founded in 1960 by the novelist Raymond Queneau and mathematician François Le Lionnais, the group was dedicated to, in their words, ‘the seeking of new structures and patterns which may be used by writers in any way they enjoy.’ The group was a loose collective, and placed great emphasis on the notion of ‘play’, as evidenced by their gloriously ludicrous membership rules. Once invited to join, a member is never allowed leave. In the event of their death they are excused from attending future meetings but remain part of the group – their absence always being minuted as ‘inexcusable’. The only relaxation of this rule stipulated that a member could, in extreme circumstances, commit hari-kari at a formally constituted meeting. As Perec’s biographer David Bellos has pointed out, ‘no one has yet taken advantage of this provision’.

By imposing structures – or constraints – on composition, OULIPO writers sought to produce new and interesting works. Examples included the game ‘S+7’, in which every noun in an existing story is replaced by the noun seven places along from it in the dictionary; the use of palindromes; the repetition of literary tropes and styles; the creation of ‘univocals’, which are poems where only one vowel may be used; and the form that was to most inspire Perec, the ‘lipogram’, writing which excludes a particular letter.

For Perec, whose novels turned on erasure (a not-unconscious method of writing obliquely about the complex absence of his parents), the lipogram proved irresistible. To exclude a letter from a piece of writing was a singular challenge. But what about a whole novel? Perec’s 1969 novel La Disparition (translated, astonishingly, into English by Gilbert Adair as A Void), featured a group of companions searching for their lost friend, Anton Vowl. While writing the book Perec sought out words lacking the letter ‘e’, compulsively scribbling them down. He forced his friends to have conversations which didn’t feature the letter, held hilarious dinner parties where only ‘e’-less food was available on the menu. But for all its playfulness, it is in the end a book about mourning – the narrator is unable to use the words père (father), mère (mother). And La Disparition, literally ‘The Disappearance’, was the phrase stamped on the orders which sent his mother to the gas chamber. This novel remains perhaps the greatest of OULIPO’s achievements.

Outside of the universities, it is hard at first glance to imagine a place further away from the literary play of Parisian intellectuals than Brisbane in 1981. For the previous 13 years, and for another six years to come, it was dominated by its premier, Joh Bjelke Petersen. Bjelke-Petersen held on to power through his coalition with the Liberal Party, and through the malapportionment of electoral districts such that the worth of a rural vote was considerably greater than that of an urban one. (The deliberate manipulation of electoral boundaries to create partisan-advantaged districts is usually referred to as a ‘gerrymander’. This portmanteau word combines the surname of the Boston Governor Eugene Gerry, who first engaged in the practice, and the shape of the district his manipulations created, said to resemble a salamander. It seems a particularly Perecian construction.)

As the 1987 Fitzgerald Inquiry was to reveal, Bjelke Petersen’s Queensland was characterised by corruption and attacks on civil liberties. For example, in 1971, during a tour of Australia by the South African rugby team, he imposed a month long state of emergency. This gave his government and the police unlimited power to quell anti-apartheid demonstrations (or any others). By 1977, all demonstrations were banned. Quelling such demonstrations was, he said in an OULIPOian turn of phrase, ‘great fun, a game of chess in the political arena’.

Despite this, the French Department at the University of Queensland was thriving. The previous year it had played host to the novelist Michel Butor, famous for his 1957 novel, La Modification, written entirely in the second person. The novelist and critical theorist Jean Ricardou had visited, as had Alain Robbe-Grillet.

Perec had been invited to Queensland by Professor Jean-Michel Raynaud. In an email to me his colleague Peter Cryle – now Emeritus Professor at the University of Queensland’s Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities – described Raynaud as ‘a thoroughgoing Voltairian, for whom irony and wit were fundamental to thinking and living’.

Raynaud picked Perec up from the airport and delivered him to his accommodation at Spot Flats – a complex covered in polychrome spots – on the Brisbane River. The next day Raynaud took him to his office at the University’s St Lucia campus. Perec was delighted to find Raynaud in possession of a brand new Olivetti ET221 typewriter, with extraordinary features such as page memory, a method of programming typeface and a daisy-wheel printer, on which Perec was moved to write – ‘in two hours flat’ – a univocal poem containing words only featuring the vowel ‘o’, as a celebration of the daisy-wheel. The poem was, he wrote with mock earnestness to friends in Paris, ‘a masterpiece whose dying fall is as fine if not finer than the Sistine Chapel’. (Unless otherwise noted, all quotations from Perec’s letters are drawn from David Bellos’ biography.) After Perec’s death, Cryle told me that Raynaud used the typewriter to write a book on Perec called Pour un Perec lettré, chiffré. It followed a pattern whereby the letters of Perec’s name were progressively blackened by a kind of typographical cancer.

Perec’s duties at the University were light: he had to teach a class on Friday afternoons, which he used to drill into a selection of final-year students – and most of the staff of the department – the fundamentals of OULIPOian writing. He also, with some enthusiasm, spoke to them about the detective novel he was writing – “53 Days”.

When not teaching or enjoying the glories of Raynaud’s typewriter, Cryle told me that ‘with Raynaud’s help and complicity, Perec visited what Raynaud called the local ‘wonders’: things that were marvellous and amusing at the same time’. He visited Surfer’s Paradise, did jigsaws with Raynaud’s children, and was baffled by marsupials. He also helped organise and curate an exhibition of his work at the University library, taking it upon himself to type up – perhaps on the Olivetti! – the legend-cards himself. Cryle notes, ‘It was not a matter of being a superior Parisian. Perec never seemed inclined to be condescending.’

What Perec made of the prevailing political climate remains a mystery. Says Cryle, ‘Perec was almost always playful. He wasn’t given to talking earnestly about big political questions. He’d probably had enough of that in Paris [after the 1968 uprisings] to last him for a while’. However, throughout his life, the political remained for Perec deeply personal. According to Cryle, ‘Those things weren’t taboo. I do recall that he talked at some length one night with a very small group over dinner about his Jewishness and his Polish refugee family.’

For Perec the ambiguities of his family history fed into the form and subject matter of his literature – and if they often had to be come at obliquely then that was because to come at them directly was to risk turning them into melodrama, or worse, cliché. It was not only the nouveau roman set who were suspicious of literary convention, and of the ‘speaking subject’. Perec would return to this concept again and again, especially in his 1979 novel, La Vie mode d’emploi – translated into English by David Bellos as Life A User’s Manual.

The novel takes the strategies of OULIPO to their extreme, and then goes beyond them. It is richly comic, it is encyclopaedic, it incorporates a dizzying number of literary tropes and styles. The book is a mystery, it is a bildungsroman, it is as precise as a Swiss watch, and barely contains its own exuberance. The action unfurls in 99 rooms – over the course of one second. The novel is complete, but the puzzle at the heart of it is not.

Briefly, the ‘action’ all takes place in a block of apartments at 11 Rue Simon-Crubellier. A resident, Bartlebooth, wishes to spend the last 50 years of his life (and all of his fortune) engaged in a single project, ‘an arbitrarily constrained programme with no purpose outside its own completion’. He will spend ten years learning to paint. He will then spend 20 years travelling the world and every two weeks painting a watercolour in a different port, for a total of 500 paintings. Each will be sent back to Paris and made into a jigsaw. On his return, he will do each of the jigsaws, one every two weeks, exactly 20 years after it was painted. As each jigsaw is completed, it will be dipped in a solution that completely erases the painting, and with it all evidence of his project.

Famously, the book travels around the apartment from room to room on a ‘knight’s tour’ – the chess conundrum in which the knight, with its L-shaped pattern of movement, lands on each square of the chessboard, but on no square more than once. To make things more difficult, Perec’s board – the plan of the apartment – is 10×10 instead of 8×8. He starts the novel in the apartment on the point of the grid with the co-ordinates 6,6 and ends it on 9,9, thus opening and closing the quotation marks of the novel.

To enumerate the arbitrary constraints Perec himself built into the construction of the novel would double the size of this essay – dictating within each chapter references to particular emotions, animals, body positions and reading material. Each chapter contains some reference to another of Perec’s works; it contains a reference to something he encountered on the day he was writing; it contains a verbatim quote from another novel (Joyce, Proust, Melville); it contains a reference to its numbered place on the grid, for example, the opening chapter at point 6,6 mentions in passing that one of the characters has a key-ring with a double six domino on it.

But Perec had not simply produced a masterpiece of OULIPO constraints, but a masterpiece of OULIPO hidden shadow. Of all the concepts of OULIPO that fascinated Perec, perhaps the most crucial was that of the clinamen. Coined by Lucretius to describe the unpredictable swerve of atoms in his version of physics, it was adopted by the OULIPO set as – quoting Paul Klee – ‘the error in the system’. In the structure of Life A User’s Manual it is displayed most emphatically in the knight’s tour generating only 99 chapters in a 10×10 grid. In content it is the failure of Bartlebooth to complete his task, due to factors that cannot be programmed, such as the growing complexity of the puzzles as the puzzle-makers grows in skill, and his own increasing blindness and loss of dexterity. He dies with only 439 puzzles completed, 61 are incomplete (both 439 and 61 are prime numbers, Perec noted in his journal). The humanness of humans has again caused a disturbance in the system.

After Queensland Perec toured Adelaide, Canberra – what must he have made of the Australian capital’s strange marriage of urban planning and occult geomancy? – Sydney and Wollongong. He lectured on his work, predominantly on Les Choses which was a set text on many of Australia’s first-year French Studies courses. In Brisbane and Canberra he hosted screenings of his 1974 film, A Man Asleep.

In Sydney he stayed with Ivan Barko, then McCaughey Professor of French at the University of Sydney. ‘Perec was a very pleasant and appreciative guest to have in the house,’ Barko told me by email, and apparently retained his fascination for the strange and unconventional:

We remember taking him for a drive one afternoon. He had said that he was usually taken to view the beaux quartiers and the traditional tourist spots. So on my wife’s suggestion we drove out to La Perouse and Frenchman’s Bay via Bunnerong Road (i.e. the Port Botany area, past the Bunnerong Power Station). Apart from the unconventional beauty of those industrial landscapes, Perec was delighted with the weather: a storm was brewing and the dark clouds and the threatening colours of the sky were highly dramatic. He loved it all.

However, says Barko, ‘what Perec appreciated most was the privacy: he spent all his time writing (and smoking) in his room’. What he was writing remains mysterious. As he wrote to his partner Catherine Binet:

My stay here is drawing to a close… Three weeks with a lot of travelling. That depresses me because my book is very much on my mind… I am itching to get to it completely.

He had, he told her, only completed the first one and a half chapters.

Perec’s last, unfinished novel “53 Days” is his attempt at the sort of detective story that had always fascinated, shot through with the sort of literary plate-spinning to which he had devoted his life. The narrator, a teacher in a fictitious French colony called Grianta, is summoned by the consul of the colony to investigate the disappearance of the famous crime-writer Robert Serval, who the narrator knows only by reputation, but who, in Serval’s final telephone call, has been chosen by the writer to find the clues to his disappearance in the manuscript of his final book, The Crypt.

What follows is a dizzying series of moves, bringing together the techniques of the detective novel with the techniques of OULIPO, and Perec’s own obsession with literary sleight of hand. Within a few pages the narrator is narrating for us, the reader, large chunks of Serval’s book, which itself features a detective called Robert Serval (in the manner of Ellery Queen – although, as the narrator points out, Ellery Queen the author was in fact two writers, Fred Dannay and Manfred B Lee). Serval (the detective) is trying to solve the mysterious death of Rouard, the naval attaché at the French embassy in the fictitious Nordic city of Gotterdam. Searching Rouard’s room he finds, fallen behind a radiator a possible clue – a detective novel called The Magistrate is the Murderer, by a writer called Lawrence Wargrave (a book that had previously appeared in Life A User’s Manual). The narrator then, with a straight face, narrates the plot of this new book – so we now have Perec narrating the story of a narrator, who is narrating the plot of book within a novel, the plot of which, he is narrating to us.

What is particularly exhilarating – and, it being unfinished, ultimately frustrating – about reading “53 Days” is that there is a real sense that Perec himself hasn’t worked out where the book is going. In the published version (translated by David Bellos and Harry Mathews) the manuscript breaks off after 93 pages, followed by some 150 pages of notes – lists, diagrams, acrostics, puns (Stendahl = Shetland), schedules, mathematical formulas (the nine ways that ‘53’ can be generated by the Fibonacci sequence for instance) and, tantalising questions about where the book is actually going, for instance:

7 witness to find

8 Places to locate

9 On that score also the book comes to his rescue, the place is a crypt, id est a cave

10 The corpse is found

11 So that was really it

12 Yes but how, who, why?

Indeed.

References to Australia abound and are, in the way of Perec, oblique. Gino’s Restaurant in Brisbane, where he ate pizza with colleagues, becomes the main restaurant in Grianta, while the wine he drank that night, Hill of Grace, is reversed to become Grace Hillof, a murdered nightclub hostess. One of the books within books within books on which the mystery hangs is called The Koala Case Mystery – one can’t help feeling that Perec may have felt a certain physical affinity with the mop-haired marsupials – while students of Sydney railway timetables will be amused to read of a British commando unit consisting of ‘five Englishmen, Sutherland, Oatley, Mortdale, Penshurt, Sydenham; three Canadians, Redfern, Rockdale, Hurstville; one New Zealander, Kogarah; two Frenchmen, Tempe, Como; [and] one Lebanese, Jannali’. And the Olivetti ET 221 that Perec so loved becomes the earlier Olivetti Lexicon 80E, leading the narrator to a fateful encounter with the only typist on the island to still use the ancient machine, the enigmatic Lise Carpenter.

We will never know how Perec intended to finish “53 Days”. However, one section of the notes is intriguing. Under the journal heading ‘Who Wrote the Book’ there is the following exchange Perec may have planned for the end of the novel:

P: A novelist we met at… He is called GP apparently he adores all sorts of problems. We gave him a number of key words, themes, names. It was up to him what he did with them.

S. You weren’t disappointed with the result?

P. I haven’t really read the book…

S. But why the title, 53 Days?

P. It’s the time it took Stendahl to write La Chartreuse de Parme… That was actually what gave us the idea of the challenge: to take 53 days to write a novel… In fact, he took a lot longer. We had made allowances for overruns, but in the end we had to breathe down his neck.

Could it be that the great literary disguise artist was finally going to appear in a novel as himself?

Perec arrived back in France in October 1981 exhausted. The last few weeks in Australia had been gruelling. He had a constant pain in one leg, and a wheezing in his chest. Perec was seldom ill, and struggled with his new condition. In early February 1982 he checked into the Hôpital Chirurgical d’Ivry. There he received the news that he had been expecting. He had a tumour in his lung. It was inoperable.

Perec died on 3 March, 1982. “53 Days” remained unfinished. As with Bartlebooth and his jigsaws, the puzzles had become too complex, and Perec had suddenly become old. And, as with everyone, his humanness remained the ultimate clinamen – whatever the best laid plans.

In writing this article I have relied on email correspondence with a number of individuals who met and worked with Perec in 1981. I would particularly like to thank Peter Cryle, Ivan Barko, Colin Nettelbeck, Meaghan Morris, Keith Atkinson, and Anne Freadman. I would also especially like to thank Dr Joe Hardwick at the University of Queensland for his assistance in accessing background material and images.

Works cited

Bellos, David (1993) Georges Perec: A Life in Words (London, Collins Harvill).

Perec, Georges (2000) “53 Days”, trans. David Bellos (Boston, Verba Mundi).

Perec, Georges (1997) A Void, trans. Gilbert Adair (London., Collins Harvill).

Perec, Georges (1987) Life A User’s Manual, trans. David Bellos (London, Collins Harvill).

Raynaud, Jean-Michel (1987) Pour un Perec, lettre, chiffre (Lille, Objet).