[Vidal’s generalisation] is subtly honed to provoke derision from precisely the sort of literal-minded types who would ask such questions earnestly in the first place—assorted journalists, rationalists, theorists, pundits, pedants—those peers, in other words, whom Vidal seemed to delight in antagonising.

Craveñho’s Universe

Ben Etherington on the first question to ask of the Craven phenomenon

In early 2016, a writer from Western Sydney, let’s call him Lucas Carmanito, expressed some opinions in Meanjin. It was a self-described ‘screed’/‘tirade’ against… well, a lot of people. Or, at least, a lot of figures standing in for people: ‘[those] with fantasies of finding a home amid [artists]’, ‘arts community dreamer’, ‘social arts hopeful’, ‘change makers’, ‘king creators’, ‘uninvited guardians of language’, ‘political animals’, ‘demi-gods of arts management’, ‘small masters of today’, ‘social climbers of the arts’, ‘anti-artists’, ‘phoneys’, ‘vampires in our midst’, ‘fakes’, ‘hucksters’, ‘devious characters’, ‘sly culture creepers’, ‘malignants’, ‘noxious weed-lingerers’, ‘Melbourne literati mafia’, ‘cultural gorillas’, ‘Melbourne-centred lit-scene mobsters’, ‘resident fakes’, ‘anti-art overlords’, and ‘cynical shysters’. That several of these figures evoke the kind of sharp-taking film character that talks about ‘wise guys’ was no coincidence. Gore Vidal was the presiding muse, and Carmanito began by glossing one of his provocative generalisations:

It doesn’t take a PhD in literary theory to see that Carmanito was preparing himself for highly self-conscious rhetorical performance. He sustained this heightened reflexivity and figurative hyperbole throughout. Here are just two further instances:

Since it will be called reactionary drivel to say so in the current climate, I might as well pre-empt accusations of Mark Latham levels of bilious, cuckoo filibuster and borrow Holden Caulfield’s refrain: these people are phoneys.

Observe their capacity to charm crowds online and in real life without once stepping outside the bounds of accepted bourgeois-liberal consensus like angels twerking on a pin.

Before it came refer to legislative obstruction, ‘filibuster’ referred to the pirates who raided Spain’s Caribbean colonies – an appropriate word choice for a rhetorical posture that dons the pirate’s tricorne like a boy intent on demolishing his playmate’s sandcastle. Nevertheless, most of the responses elicited by the essay were earnest and literalistic. To take one example:

If Carman[ito] had actually named names – if he were able to point to issues that were structurally wrong, or identify actors who were genuinely going against writers’ best interests, or provide evidence of any of the issues he alludes to – I would have some respect for the decision to publish this.

It took a critic of quite different character to point out that such responses succeeded only in sending the handle of the rake, Sideshow Bob-style, into the respondents’ foreheads:

virtually no-one seems to have considered the rhetoric of Carman[ito]’s essay (particularly its heavy use of irony and hyperbole) or its deployment of a traditional genre – the jeremiad – whose central features are the use of bitter invective directed at widespread targets and an apocalyptic tone.

As it happens, this critic does have a PhD in satire. He identified other salient formal and rhetorical effects as he built to his main contention:

The essay’s lack of decorum – its refusal to abide by the rules of politeness – is an open challenge to middle-class professionalism, which, according to Carman, is the anti-artist’s natural mode of being … For all of its hyperbolic rhetoric, the essay is a call for a limited form of underclass literary revolt.

This was an effective counter-riposte, which, combined with the original essay and the responses it provoked, presented a neat parable of contemporary Australian letters. An outlandish performance by a Sydney writer in a Melbourne journal elicits a string of injured responses from mostly Melbourne critics and literary professionals, before the episode is brought to a close by a Newcastle academic (recently relocated from Melbourne). Though they share a common domain, each spoke from within distinct sub-fields and to slightly different audiences. In an era of fragmenting publics, such moments are not so much debates as the sparks that fly when vocational and professional vectors collide. The attention-grabbing artist, the virtue-signalling professional, and the dispassionate critic each receives applause from their respective audiences in form of clicks and likes.

The Carmanito affair, and Emmett Stinson’s contribution in particular, got Critic Watch thinking about rhetoric in Australian literary criticism. How do such codes of performance and reception play out in the field of evaluation? It is not a straightforward question. To call attention to the performance of literary criticism can pose fundamental challenges for the way in which we habitually read and respond to acts of evaluation. We are used to thinking of creative authors as ‘dead’ insofar as the reading of their work is concerned. Language and the creative process, we understand, have their own kind of agency. Critics, though, are very much alive – their expressed judgements and opinions get read and discussed as though they were the unmediated extrusions of their personalities.

There are good reasons for this. The most convincing account of the nature of aesthetic judgements in societies in which artistic production is separated from its reception remains that provided by Immanuel Kant, who posited that judgements of taste are ‘subjectively universal’. When it is claimed (as opposed to merely asserted) that x is beautiful, or ugly, or so lavishly wrought as to overwhelm the senses and make further judgement impossible, the subjective evaluation seeks general acceptance. There are no objective grounds for proving this, so one must persuade others. This is the theoretical, as opposed to commercial, rationale for reviews of art. They are acts of persuasion that seek to establish the truth of subjective impressions. To think of criticism without a purposive subject can feel like trying to grasp the existence of the universe before the big bang. We might call it the critico-intentional fallacy.

The Carmanito affair did not concern reviewing, but it helps to focus our attention on the rhetoric of criticism. If his essay is most successfully read as a rhetorical performance, does it follow that we should diffuse the critico-intentional fallacy and read criticism, including reviews, primarily as rhetorical performances? Should engaging with acts of evaluation and opinion-making become primarily a matter of appraising each other’s complex positioning, with attention to rhetoric, style, form and a deep sense of social context?

When it comes to reviews, at least genuine ones, Critic Watch thinks not. Evaluative judgement is at the centre of the review and an abyss of relativity awaits if we treat this as only a function of social position and/or one kind of speech-act in wars of prestige. The illusion of the judging individual is necessary because we believe that aesthetic experiences have real qualities and that describing them attests to these qualities. But this does not mean that we should disregard the language and style of criticism, and the worldly interests that bear down on them.

This edition of Critic Watch is about the formation of critical voices and the rhetorical grooves which they furrow. The accustomed rhetorical styles of seasoned critics allow certain kinds of judgements to appear in the public sphere and shut out others. These voices come to have a dominant role in shaping our collective sense of the literary present. We might disagree with all of a particular critic’s reviews, and even despise the reviewer, but we are drawn to them nevertheless because we are habituated to the prism of taste through which pass the objects under review. In turn, institutions and audiences come to expect certain kinds of performances. For instance, ‘professional ranter’ Luke Carman was headline act for a session titled ‘RANT!’ at the Mudgee Readers’ Festival in August. Whether or not Carman naturally feels himself to be Carmanito, it’s now expected that he be ‘entertaining, funny and occasionally naughty’.

Broadly, I want to distinguish two rhetorical poles towards which critics tend to gravitate: the literalistic and the performative. This distinction is at best heuristic, but bear with me. The literal critic is literalistic because she believes that the word of her judgement should align as closely with the truth as possible. Her gaze assiduously is trained on the object, and it is the object that occupies the review’s centre ground. Literalistic critics tend to favour a prose style of refined elegance with restrained witticisms girded by an ethical bearing. The performative critic, on the other hand, is theatrical and the theatre created by her response is her form of truth-making. Performative critics have access to an unconstrained vocabulary and tend to be less concerned with argumentative consistency and descriptive accuracy. If they have a commitment to truth, it is to the manifold appearance of their sensibility as it encounters aesthetic objects. Literalistic critics tend to be those whom critics themselves respect, performative critics the ones favoured by editors because their performances draw a crowd. In Australia we might place Peter Craven and Elizabeth Farrelly at the performative pole, and Kerryn Goldsworthy and James Ley (and many besides) at the other.

Though not mutually exclusive, the grooves furrowed by performative and literalistic critics do not readily run together. The literalistic critic finds it difficult to be overtly performative lest it harm her reputation for clarity and ethical conduct. The performative critic avoids the earnestness of literalism because, like a stand-up comedian, she fears yawns above all. That the majority of criticism and reviewing tends toward the literalistic can be attributed to the critico-intentional fallacy. The literalistic critic is always conscious that her character and taste are being scrutinised even as she scrutinises a work. Overtly performative critics are therefore quite rare. They must be prepared to endure ad hominem attacks provoked by their rhetorical extroversion and, potentially, reduced publication opportunities if they cross the line of etiquette too often. Like Luke Carman, performative critics are often also creative writers, accustomed as they are to the gap between their scribal and private selves.

The performative specialist critic is a particularly rare creature. It is a position that few desire to occupy or are capable of doing so. Over the last twenty-five years, one figure has managed resolutely to make this position his own in Australian literary criticism: Peter Craven. The scale of Craven’s output alone compels awe, even when the inevitable repetitions and shortcuts are taken into consideration. Critic Watch logged a total of 1738 pieces of journalism between 1993, when the Craven machine really got going, and 2016, of which 853 were reviews. That’s an average respectively of around 75 and 37 per year. (Those interested in reading up on other extrovert critics should consult Angela Bennie’s recent Crème de la Phlegm: Unforgettable Australian Reviews.)

If public stoushes are an index of a performative critic’s success, Craven’s war diary includes battles with Simon During (over Patrick White’s legacy), Mark Davis (over generationalism), Ian Syson (over Robert Manne), Morry Schwartz (over the editorial direction of the Quarterly Essay), Ken Gelder (over literary canons), Guy Rundle (over a theatre review), Sophie Cunningham and others (over the Aboriginal content of the Macquarie PEN Anthology of Australian Literature), Julian Meyrick (over theatre reviewing), and even friends like Hilary McPhee (over a hatchet job on Richard Flanagan’s novel Gould’s Book of Fish), not to mention the plethora of scornful remarks and despairing letters to the editor that litter Craven’s archival presence. Each attack has enlarged, or at least refreshed, his readership.

The most amusing of these stoushes was with fellow performative critic Guy Rundle. It was provoked by a negative Craven review of a Rundle-scripted Max Gillies show. In his reply, Rundle began with Craven’s penchant for hyperbole in both praise and criticism – ‘one moment he’s drooling on your jacket, the next planting the knife’ – before lampooning Craven’s prodigality:

In between those there’s words. Lots and lots of words, dictated into a machine, and then reeling out of the paper. They’ve have [sic] long since become a single bolt of cloth, from which one cuts the length required, and no one really knows whether they have a public following or not. Tired, overstretched editors simply know that they can be cut to fit, and they have that literary feel.

Though a caricature, the substance is undeniably true. Critic Watch lost many precious hours simply trying to ascertain the scale of the Craven phenomenon, let alone assess it. Rundle’s recourse to innuendo and irony were wise choices, fighting the performative critic with his own weapons. Combined with feigned intimacy and disarming praise, Rundle called on the tactics Craven long has used to gain the upper hand in public disputes. In his reply, Craven started by calling Rundle ‘my old mate, Guy’, ironically recounted the charges made against him, before defending himself point by point and jabbing back. Whichever way the judges may have called it, the bout did no harm to either’s visibility and had not the slightest impact on their reputations and careers.

Six years earlier, Craven was attacked from a very different angle. Peter Hayes’s 2004 essay ‘The Stuff of Nightmare: Peter Craven’s Influence on Australian Literary Culture’ was not so much a jeremiad as a despairing act of rationalism. Over 4300 words and 78 footnotes, he had a go at itemising all the stylistic faults and ethical inconsistences that he felt marked those reams of Craven print: factual inaccuracies, non-sequiturs, catachreses, clichés, self-regard, name-dropping, prolixity, opining, quip borrowing, assertions without evidence, unthinking canon worship, repetitions, logical fallacies, unabashed partisanship, reputation leveraging, log-rolling, critique hedging, lack of rigour, lack of restraint, lack of professionalism, shrillness, windbaggery, soapboxing, abuse of power. In sum, ‘he lacks the true critic’s authority, but has unlimited power to voice his opinions. It would be hard to imagine a situation more grotesque.’

It was the literalistic critic’s attempted revenge. If only the world held the performative critic to his word they would see that he’s a phoney! On this one occasion Craven decided that engagement was not worth it, offering ‘no comment’ when Hayes’s attack got picked up in the Sydney Morning Herald. He may just as well have quoted the famous American gossip Walter Winchell. When accused of having ‘neither ethics, scruples, decency nor conscience’, Winchell replied, ‘let others have those things. I’ve got readers.’ The next year, 2005, Craven published 131 pieces of journalism including 48 reviews, his most prolific ever.

The first question to ask of the Craven phenomenon is not ‘why?’ but ‘how?’ Whether you agree with Hayes or Christopher Bantick, who rose to defend Craven’s fearlessness, the more difficult thing to get your head around is how a critic of Craven’s sensibility and style managed to capture and occupy the centre ground of Australian literary criticism. How and when did the rhetorical formation we know as ‘Peter Craven (critic)’ begin? How has it evolved? What has been its cumulative impact on Australia’s literary culture?

The earliest trace Critic Watch found of Craven is a letter written to his friend Michael Heyward in late January 1980 which is held in the archive of Scripsi magazine. Craven was then just shy of thirty. Heyward was in London that summer and in his letter had related news of a meeting with the English poet Basil Bunting. Craven tells Heyward that he ‘skipped about the house positively exulted by the contact high at one remove’. He then relates his own encounters with the ‘literary high and mighty’: ‘bumping into Vin (in particularly sunny mood) last week resulted in some plonk quaffing at University House.’ Vin, the poet and Professor of English Vincent Buckley, treated him to ‘various flattering and chastening remarks about my academic prospects’. If there are hints of the Craven to come in the exaltation at literary celebrity and louche ‘plonk quaffing’, at this point he was caught between hopes for casual tutoring, applications for postgraduate funding, and amorphous literary aspirations.

The latter would gain form when Craven and Heyward took over the English department’s ailing poetry magazine Compass. They renamed it Scripsi and widened its scope to include narrative fiction and essays. A 1982 profile of the two editors by Stuart Sayers for The Age has a shot of a thickly bearded Craven, dark hair flowing to his bohemian’s blazer, casually laughing in the direction of the camera while Heyward, smiling but with eyes cast down, walks stiffly beside him. They tell Sayers that they are ‘literary journalists’ rather than ‘dry as dust academics’ and boast of their ability to entice renowned authors and critics to write for their journal, often without pay. In its early issues, though, Scripsi did not look very different to most literary journals housed in academic departments across the world. It contained poems and prose by those both up-and-coming and established in the local literary scene as well as essays on fashionable writers and theorists largely written by friends, acquaintances and academics. An early issue was given over to James Joyce’s work, the subject of Craven’s postgraduate research. Contemporary Australian magazines like The Lifted Brow, Kill Your Darlings, and Seizure look a lot more like literary journalism.

As the 1980s wore on, more literary celebrities from beyond Australia appeared in the journal – Germaine Greer, Maurice Blanchot, Northrop Frye, Salman Rushdie, Susan Sontag, Ian McEwan – as well as literary theorists in translation and niche writers like the Cambridge poet J. H. Prynne. The editors even approached the ageing Simone de Beauvoir. The presence of such figures in a new Australian journal certainly attested to the editors’ tenacity and flamboyance, but the fact of writing for an Australian magazine appears to have had little effect on these writers’ choice of subject matter. Scripsi’s contributors did not collectively produce a recognisable house style like the small magazines attached to influential aesthetic movements. Its innovation was its editorial approach. Craven and Heyward were concerned above all to be selective and international; an ambition not dissimilar to that attending the relaunch of the English literary magazine Granta in the 1970s. The juxtaposition of the ‘best’ of the local with the stars of the North Atlantic literary world was a conscious riposte to Australia’s cultural cringe and gave the journal a distinct identity and cachet. It provided emerging Australian writers with the sense of writing on a global stage, and many have commented that this was fresh and invigorating. Craven and Heyward’s instinct for bestness connected with a new spirit in the literary scene, and this instinct clearly runs through the corpus of Craven’s work as editor, commentator and critic.

The tone and style of Craven’s contributions to the magazine bear only some resemblance to the Craven that would make Hayes despair two decades later. A 1985 essay on the figure of the artist in Malouf’s novels has recognisable Cravenisms (comparisons to Turgenev, a somewhat breezy tone), but the prose is tighter and its purpose more academic. The Scripsi archive holds a cover letter and CV that Craven submitted for a full-time tutoring job at the University of Melbourne’s Department of English in 1986. It outlines Scripsi’s achievements largely in academic terms. It also reveals that he had been teaching casually for the department since 1984, that he’d sought out publication in foreign journals, and that a volume of his criticism was under consideration by Picador Australia. There is also a letter to BHP penned by Heyward in the same year nominating Craven for a ‘Pursuit of Excellence Award’. It tells of his years in the 1970s ‘enjoying prolonged bouts of unemployment’, during which he made his way through the Western classics, and the excellence of his nevertheless unremunerated labours for Scripsi. This appears to have been a pivotal moment. Craven was trying to leverage Scripsi’s success to gain a more secure foothold in the academy, or, at least, proper financial support for his work as editor.

Two talks given at this time are helpful for understanding Craven’s early attitudes to literary criticism. In the first, delivered in 1986, Craven lays out his ideas about the plight of literary criticism in Australia. Academic departments may sometimes give ‘shelter’ to critics, but their basic relation to literary culture is ‘parasitic’. Book reviewing’s core purpose is evaluative and its basic duty is to establish whether it is worth a reader’s time. The problem with Australian criticism is that it does not know ‘how to praise or blame’. Criticism should not be mild but is entitled ‘to its own blood & thunder’. In the second, delivered in 1987, Craven lays out his ideas about periodicals of criticism. The reason for the impoverishment of writing by Australian academics is the ‘relative absence of a higher journalism’, by which he means the likes of the TLS and London Review of Books. Academics have no competence for short-form reviews and no local outlet for longform yet topical essays. Scripsi, he claims, had taken up this slack: ‘it has to substitute for that mediating higher journalism Australia lacks’. He thus regarded Scripsi’s success primarily as a structural matter. Malouf and Hughes are prepared to write for it because ‘no one more central is doing it [i.e. higher journalism]’.

Craven’s model at this time appears to have been highbrow university-based literary critics like Hugh Kenner and Frank Kermode, both of whom appeared in Scripsi. However, he could not get a foothold on staff at Melbourne – Buckley had retired and was soon for the grave, and the Foucauldian Simon During (PhD Cantab) was the department’s golden boy. Nor could he generate the income necessary to carry on indefinitely as Scripsi’s editor. To pursue a career in ‘higher journalism’, he could have followed one of his other heroes, Robert Hughes, to London or New York. But there is another key ingredient in Craven’s critical formation: a deep-seated cultural nationalism. This is apparent in an attack essay on Clive James that appeared in the London Review of Books in 1988 (a salutary year for cultural nationalism) – a piece that drips with the anxiety of influence. James has stooped too far to the popular and become a ‘sharp-talking deified moron’: ‘Shakespeare’s Hal said to that gross man Falstaff that the grave gaped three times wider for him, and it gapes three times wider for the star journalist who in the end is just a journalist. The more he clings to his success, the more he will be forced to revert to the mediocrity and ordinariness he once did so much to eliminate or transmute.’ The piece is not without ambivalence, though; jibes at ‘verbal self-indulgence’ are balanced by an admiration for James’s capacity ‘to marshal his high culture in the service of the belly laugh’.

At the centre of this upstart’s attack is the claim that James is no longer really Australian. He is a ‘stylised distortion of what Britain sees itself as’ and his attempts to reckon with contemporary Australian literature are ‘amateurism posing as expertise’. Many of the essay’s lines of attack (and praise) could easily be trained on the content, style and tone of Craven’s later reviewing, but not this charge of foreignness. To understand his trajectory it is important to see that while nearly all his critical models came from the North Atlantic cosmopolitan sphere, he gave every sign of being determined to realise his ambitions through homegrown platforms. In this respect his disposition conforms to what Mark Davis calls the ‘cultural mission’ of Australian literature at this time. The essay on James was a calculated missive to the kind of metropolitan literary culture for which Craven yearned yet from which he resolutely turned. If the quips and high-mindedness read transparently as Verleugnung, the commitment to Australia and its print culture has given Craven’s career its distinctive shape and rhetorical limits.

It’s always dodgy to throw the word ‘literature’ around too freely. In a milder way, it’s a bit like throwing the big words, such as love and god, around. (This doesn’t mean these words can’t have a meaning; it’s simply that they don’t have much chance of being anything but cliches if you’re too free and easy with them.)

This comment comes in a meandering and apparently unprompted piece on ‘Literature Writ Large’ published in The Age in August 1992. Craven was still the editor of Scripsi but things were quite different to 1987. Beginning with a trickle in the mid-1980s, Craven’s freelance output steadily increased through the late 80s and early 1990s. He had a brief stint as a theatre critic for The Australian in 1990, but he first gained real traction writing for his hometown broadsheet. Six months later, he gave up the editorship of Scripsi and became a de facto staffer for The Age, doing interviews and reviews for the weekend supplement as well as comment pieces, obituaries and sundry other. In all, Critic Watch logged 50 pieces of journalism in 1993. Craven was now well into his forties.

The intervening years witnessed a transformation in Craven’s style, tone and approach. From disdaining critics who are really ‘just journalists’ to becoming one. From trying to create a platform for ‘higher journalism’ to accommodating himself to the realities of a jobbing critic in Australia. And the evidence is there in the prose. The colloquialisms and contractions, the direct address to the reader, the run-on parenthetical remarks that give the effect of thoughts spontaneously piling up, one after another, all while discussing an apparently high-minded topic – these are the calling cards of the raconteur style that would soon achieve blanket coverage. There were signs of this style in his early stabs at freelancing, but so too were the fingerprints of the academic milieu still evident (‘for Lawrence ontology becomes geography’).

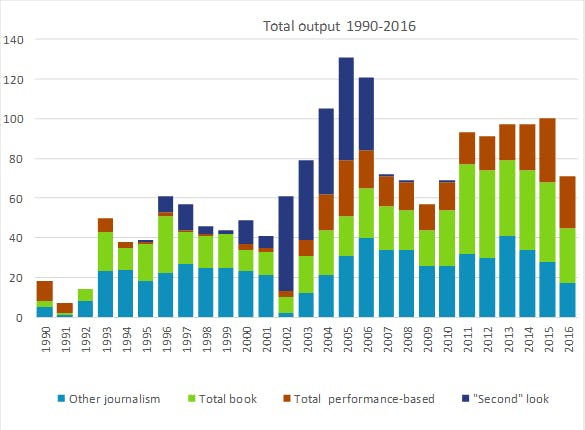

Seen from the perspective of the raw data, Craven’s freelance career has an uneven shape united only by unrelenting productivity. The data for the following graphs were gathered primarily using the AustLit database and the Factiva database of Australian newspapers. Critic Watch also conducted searches of the online archives for the periodicals for which Craven regularly contributes (the ABR, the Spectator, The Saturday Paper, The Monthly, the SRB, etc.), as well as checking the archival holdings of older publications like the short-lived Editions. No doubt a number of pieces will have fallen through the cracks, especially in the late 80s and early 90s when database collection was patchy. The trends evident in this period should be taken with a grain of salt. In all, Critic Watch logged a total of 1802 pieces between 1981 and 2016, but guesstimates that Craven’s total output in this period to be in the region of 1900-2000.

The following shows Craven’s total output from 1990-2016.

Critic Watch has broken down his output into book reviews, reviews of performance-based media (theatre, screen media, and audio), and ‘other’, which includes interviews, features, columns, obituaries, opinion pieces, essays on canonical figures, previews, and assorted trivia. The fourth form of output, ‘second look’ articles, which could just as well be called ‘stuff I have read’, is quite unique to Craven. These pieces, usually short, revisit works from Craven’s personal canon, which might be anything from Homer to an Australian novel he had positively reviewed two years earlier.

The numbers reveal that Craven is as much a cultural journalist as he is reviewer. (Kerryn Goldsworthy’s output perhaps better exemplifies the gigging literary critic of our times. A glance at search results suggests that she has been the most prolific book reviewer of her generation. She certainly has reviewed a wider spectrum of Australian fiction.) After his breakout year in 1993, Craven secured a regular column of cultural commentary with The Australian’s Higher Education Supplement, a gig he held until 2001. In 1998, he was the founding editor of Black Inc’s Best Australian Writing anthologies. This began with essays (1998-2003), then stories (1999-2003), and later poetry (2003). He was also the founding editor of the Quarterly Essay, which began in 2001. These four posts abruptly came to an end in early 2004 when he fell out with Morry Schwartz, his boss at Black Inc. Thus began an even more prolific period as a critic at large, writing reviews, features, columns and interviews across platforms at an average of 90 pieces a year. This period also saw a sharp rise in Craven’s reviewing of performance-based art, first writing on television for the broadsheets and later the theatre after he secured regular gigs with the Spectator (2008-2014) and The Saturday Paper (2014- ).

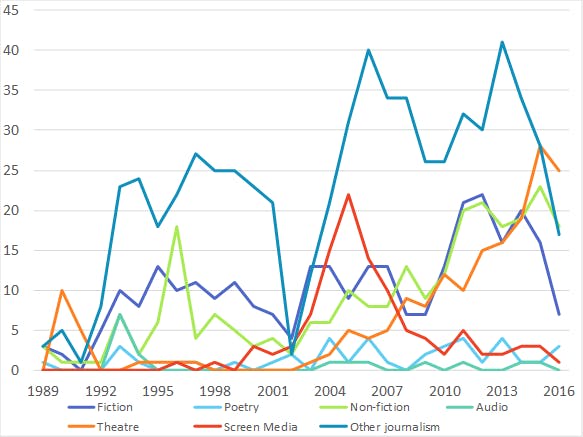

These career movements are discernible in the patterns of Craven’s reviewing of various literary genres and other cultural media:

The theatre and TV gigs stand out for their sudden rises and falls. We also see increases in certain areas to compensate for decreases in others, or vice versa, such as the fall off in reviews of fiction as theatre reviewing becomes a main breadwinner. The data set was too large to allow time to categorise by publication, but the majority of Craven’s output has been for the weekend editions of the Fairfax and Murdoch broadsheets. He has written consistently for the Australian Book Review and there are a smattering of pieces written for the liberal literary-cultural magazines and journals including the Sydney Review of Books.

A 2002 Sydney Morning Herald profile of Craven by Susan Wyndham was titled ‘The Power of One Critic’, and it was no exaggeration. On a given weekend around this time, you might open the supplements of The Australian, the metropolitan Fairfax broadsheets and the Australian Financial Review and find a Craven think piece on Australian TV, a review of the latest novel from Malouf or Rushdie, a baggy tribute to Proust or Joyce, and a short account of a favourite Grenville novel or Peter Porter collection. In the Australian Book Review you might come across one of his ‘demolition jobs’ of an established middlebrow writer. When the Quarterly Essay arrived you would read Craven’s pick of public intellectuals discussing issues of national concern. Shopping for Christmas gifts, you might pick up one of the Best Australian Writing anthologies and be exposed to his taste in poetry, fiction and non-fiction. You might even see him on television as a panellist on the short-lived ABC show Vulture. Craven was on the ABR’s board, and in 2004 he won the Geraldine Pascall Prize for critic of the year, prompting a number of further profile pieces. A survey conducted by the Sydney Morning Herald in 2005 to determine Australia’s leading public intellectuals, ranked Craven 34th (behind Rundle, Hughes, and James among critics), but he came ninth in a similar poll in The Australian a year later. Peter Hayes’s attack in Overland came at peak Craven. In retrospect, his ferocity looks like just another feather in Craven’s cap.

It may be that Craven was always heading toward becoming this kind of prolific critic writing in that sort of chatty style. His father was a sports journalist, so he had a ready model for the hack’s velocity, and any thirty-year-old that speaks of ‘plonk quaffing’ seems destined to become Peter Craven in middle age. But this should not blind us to the fact that the critical voice we know as ‘Peter Craven’ is at least partly the creation of necessity. A counterfactual scenario in which Craven manages to secure an academic post and goes on to write more tightly structured and edited essays destined for boutique essay collections (of the sort he discussed with Picador) is not difficult to conjure when you look back on the Scripsi years. Yet such has been his drive and ubiquity, the style Craven forged as a self-described ‘shirt-sleeves critic’ can seem like a natural fact, if not a force majeure. In any case, as we remarked earlier, the tendency to identify the voice of evaluation with a distinct and whole personality is constitutive of aesthetic judgements. Reading across his body of criticism, it can feel as through the man has you permanently cornered at an interminable interval at a writers festival, breath thick with Semillon and salmon pikelets, as he bitches about postmodern academics and the unevenness of Tim Winton’s prose.

Craven maintains that his bombast is nevertheless the vehicle for a Kantian commitment to disinterested taste. In the Wyndham profile, he said of his ‘demolition job’ on Robert Dessaix’s novel Corfu: ‘I would hope it was dispassionate, however much the rhetoric of the reviews might appear impassioned’. Likewise, he called his combative review of Davis’s Gangland ‘impersonal scorn’. To temporarily break the spell of the critico-intentional fallacy and to hold this rhetorical-critical structure up to scrutiny, Critic Watch will rechristen it, with apologies to Fernando Pessoa, Craveñho. This is especially necessary as the success of the style in question is premised on establishing personal intimacy both with its subject matter and reader.

The first thing to grasp about Craveñho is his speed. All aspects of his rhetoric and style are engineered to facilitate rapid execution. This is also a material fact. According to profiles, interviews and hearsay, Craveñho relies on amanuenses to type up his pieces either from voice recordings or drafts scribbled with a fountain pen. Even if such tales are apocryphal, they lend the prose the aura of having been delivered in a single stream to a receptive listener.

If speed provides the impetus, the rhetorical posture of the raconteur supplies the form that makes a virtue of spontaneity, digressions and discursive formlessness. In a study of the performance styles of writers in interviews, John Rodden describes the raconteur as ‘a storyteller whose main unit of discourse is the anecdote … Digressions and asides punctuate their interviews which sometimes must be heavily edited in order to achieve narrative flow or even coherence.’ A Craveñho review, especially of a well-known writer, will not let slip the opportunity for anecdote:

I once heard Salman Rushdie talking about a conversation he had with Elizabeth Jolley about one of her family members that shocked him and made him laugh aloud.

I heard him (Rushdie) say once, confidentially and with furrowed brow, in a hotel room, that he didn’t know how you could be Norman Mailer in New York and write about what happened in bars when your presence in any bar affected everyone’s behaviour.

I once heard Rushdie speak with reverence of the Irish because they celebrated James Joyce’s centenary by reading the whole of Ulysses on national radi

I once heard the distinguished American novelist William Gaddis say that he first read James Joyce’s Ulysses for the dirty bits.

An Indian novelist and I once played the Monty Python game that has contestants summarise Proust in 15 seconds.

Kazuo Ishiguro, a man I once played great film list games with while eating fish and chips at an Adelaide restaurant…

These typically have only a tangential relation to that which goes before or after them. For Craveñho, interest and intimacy, not discursive coherence, are the principal criteria. His reviews are full of parenthetical asides and abrupt sub-clauses, one often immediately following the other: ‘I once — thirty odd years ago — had the bizarre experience of having someone, my closest colleague and dearest friend, read one of his novels (as I remember the whole of one of his Morris Zapp academic farces) aloud to me on the phone as we screeched and stomped and fell about …’ The syntax could quickly be ironed out, but the haphazard phrasing gives the impression of a recollection coming into focus in real time.

Speed also cuts to the core of the kind of evaluation undertaken in a Craveñho review. In an interview given after receiving the Pascall Prize he stated that he never thinks too long about a work under review: ‘It sort of forms iceblocks in your head and you don’t know what you think’. The authentic judgement is the intuitive one; wait too long and reflexivity will destroy it. This fear of the loss of velocity channels Craveñho’s creative capacities into one or other type of generalisation, most frequently canonical comparisons, quips, clichés and analogies. These are resplendent in his ‘demolition jobs’:

Nine-tenths of the dialogue in Corfu consists of faintly preposterous la-di-dahisms about Maltese Knights and Turkish campaigns and the Austrian empress Sisi. It’s bad enough that the narrative voice is full of the kind of recapitulative, historically ‘resonant’ wallpapering, but it does beggar belief a little when the rest of the characters start palavering on (for several hundred words a mouthful) like Edwardian Baedekers.

It doesn’t help that the prose slurps and slops its way through a thousand mismanaged effects. Flanagan quotes Virgil, Faulkner, whoever, but seems incapable of writing the kind of prose that sings a reminiscent tune even though he tries persistently. The upshot is the kind of pastiche that doesn’t just result in anachronisms — something any work of historical recapitulation will — but falls flat on its belly time after time.

Those who lament his clichés and loose syntax miss the fact that they serve to strengthen the all-important quality of spontaneity. Clichés are the pre-formed thoughts that offer themselves when we first reach for words to describe an impression or experience. Craveñho’s refusal of elegant variation and positive delight in piling up pat phrases imbues them with the animation of thought encountering an object in real time.

This means that the work under review is refracted to readers through Craveñho’s repertoire of stock phrases rather than being described. Critic Watch read dozens of Craveñho reviews in full, and scanned several dozen more, and could not locate a single instance of sustained descriptive practical criticism. Where a passage is cited, its qualities are quickly summarised and it is left for the reader to make the deduction. Take a recent longform piece on perennial favourite Julian Barnes for the Sydney Review of Books, in which citations comprise a quarter of the review’s 3300 words. A typical gloss reads: ‘This is good writing — with an elegantly etched sketchiness that leaves it just clear of the obvious.’ What does ‘elegantly etched sketchiness’ even mean? In another review, Craveñho cites a passage of Harold Bloom’s criticism and comments simply: ‘Criticism, my dears, doesn’t get better than that.’ Before castigating him for laziness, we must remember that Craveñho is not trying to win an argument with evidence. The voice plays to a readership that is always already convinced of the value of established writers and wants to know whether their latest is up to scratch.

The unapologetic use of cliché and hyperbole when making judgements about others’ creativity brings us another key aspect of the Craveñho rhetorical posture. The work under review is berated for failing to live up to standards that Craveñho himself flouts. For instance: ‘The difficulty with Rushdie is that the wham-bam-thank-you-ma’am style is imitable … Shalimar the Clown is the latest instalment in his concerted attempt to turn himself into a cliché.’ The root word of chutzpah means something like ‘to bare’, and it is the barefaced refusal of critical care and responsibility, the comportment in which literalistic critics take pride, that gives Craveñho’s voice the sense of naughtiness. It also gives his voice the air of camp. It would be inaccurate to characterize his style as camp in general, but it certainly has the elements of irony, aestheticism, theatricality and humour that Jack Babuscio identifies as camp’s hallmarks. There is also the gleeful unseriousness about the serious that Christopher Isherwood once called ‘high camp’: ‘You’re not making fun of it [high culture]; you’re making fun out of it.’ This also is apparent in Craveñho’s reviews of popular culture. Take the following from the review of a an erotic novel by Sonya Hartnett (writing as Cameron S. Redfern): ‘They come together. My how they come together. In endless lubrication-slick conjugation with every possible appurtenance or object going into every possible orifice and with every kind of pant and grunt the well-oiled imagination can summon up.’ This is cruder than the camp that turns on the imperceptible line between irony and sincerity: if you missed the pun, Craveñho repeats it; if you enjoyed the reference to lubrication, he’ll give you two more. In a 1996 attack on Simon During for his iconoclastic study of Patrick White, Craveñho deliberately deploys camp to lampoon him before delivering one of the essay’s more aggressive insults. To During’s quip, ‘[this] seems like a community of homosexuals travelling, if this were possible, both away from and further into the closet’, Craveñho retorts: ‘Well, Simon darling, it’s not possible. This one is like nothing so much as the dumb hippie from The Young Ones.’

This long essay in the Australian Book Review was something of a statement of arrival. It showcased Craveñho’s capacity to initiate public controversy and then conduct it on his terms. A decade after applying for a job in the department in which During was ascendant, and four years after his freelancing career really had got going, Craveñho was deploying his stylistic arsenal in the broader public arena that he now had made his home. If During and cultural studies had colonised the space in which an Australian Kenner might flourish, Craveñho would decamp with the literary canon to the jungle of public opinion.

The following year his status was secured when he became the target of the upstart’s polemic. Mark Davis’s Gangland flattered Craveñho by placing him at the centre of the baby-boomer plot to deny Generation X institutional oxygen. Fittingly, Davis was then completing a doctorate in cultural studies at Melbourne University. Craveñho was only too happy to indulge his critique, furnishing it with a quip-laden review and then sharing the stage with Davis as he basked in the younger man’s iconoclasm. (Wrote Craveñho at the time: ‘Davis and I have appeared in public together so often that we have come to seem like Laurel and Hardy’.) Four years later, During had taken a chair at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore and Craveñho was making the cultural picks for Team Australia.

In sum, Craveñho’s stylistic repertoire comprises anecdotes, quips, analogies, hyperbole, clichés and ready-to-hand comparisons, all related with the raconteur’s digressive syntax and a campy chutzpah. These work together to give his criticism the atmosphere of gossip. This is not to say that it is gossipy (though Craveñho has at various times written gossip columns about writers festivals and the like). Rather, I’m suggesting that Craveñho works to create that peculiar intimacy in which the gossiper talks to the confidant about the gossipee’s business. Readers get to hear what he really thinks so long as they allow him the license to be extravagant when relating it.

Flaunting his familiarity with the authors of the works he reviews inevitably has led to charges of log rolling. Craveñho’s perennial defence is that he is capable of negatively reviewing the writers that he so obviously favours. This is a deflection, though, for the Craveñho universe does not operate according to a positive/negative logic but by inclusion and exclusion. As Joseph Epstein has written of gossip: ‘it needs a setting, a basic understanding among the gossipers, an agreement about what is of interest in the vast array of the world’s information.’ The world of gossip is that of a mutually imbricated society. Bestowing on Australian literature the quality of being society arguably has been Craveñho’s chief contribution to it. All those anecdotes about casual run-ins and wry quips made in private quarters at once manufacture literary celebrity and give readers immediate access to it. He is not so much gatekeeper as doorman to the manor. He almost never reviews debut Australian writers and when he does they invariably have already passed through an initial vetting process. His review of Nam Le’s The Boat opens by mentioning the recommendations of Helen Garner, Junot Diaz, Andrew Solomon and a New York Times critic before praising it to the skies. A review of Fotini Epanomitis’s The Mule’s Foal similarly begins by reporting on the hype that preceded it. Epanomitis, though, is tautologically turned away (‘The difficulty with The Mule’s Foal is not the rank soup it makes of its ethnic elements or the way it comes across as something midway between two unlovable SBS exhibits…’).

As has been frequently remarked, when Craveñho moved into freelancing he took his Scripsi Teledex with him. In the six years after leaving Scripsi (1993-1998), he reviewed 32 new works of Australian fiction, of which the authors of 21 had been published in Scripsi. A further three are listed among the correspondents in the Scripsi archive. Of the eight remaining, three, all by Shane Maloney, were published by Text, the firm founded by Michael Heyward, and another by McPhee Gribble, a publisher with whom Craveñho had close associations at the time. This leaves four works over which the smoke of personal entanglement does not linger: novels by Gabrielle Lord, David Ireland, Margaret Simons and the expat Madeleine St John, whose book had been shortlisted for the Booker.

In laying this out, Critic Watch is not suggesting that Craveñho could have embarked on a career as a full-time critic in Australia and avoided reviewing authors and publishers with whom he had dealings at Scripsi. Also, editors may well have commissioned reviews by writers with whom they knew he was already familiar. Nevertheless, authors who had no recorded connection with Scripsi and who released prize-winning or otherwise noted volumes of fiction in this period include Robert Drewe, Alex Miller, Richard Flanagan, Alexis Wright, Carmel Bird, Christopher Koch, James Bradley, Delia Falconer, Rod Jones, Mudrooroo, Adib Khan, Lily Brett, Sue Woolfe, Elliot Perlman, Darren Williams, Bernard Cohen, Eva Sallis, Joan London, Simone Lazaroo, Dave Warner, Gail Jones, Kim Scott, and Christos Tsiolkas. Craveñho would subsequently review works by several of these authors (often harshly), and steadfastly ignore others. The point is that they needed to gain access to the grounds before Craveñho would consider their suitability for the manor.

Critic Watch will leave it to more intrepid investigators to look into the ways in which personal relationships and affiliations may have shaped the Craveñho universe. (Davis’s book remains a good place to start.) Calling out nepotism is not the purpose of this investigation, nor is it especially necessary. It is within Craveñho’s right to pitch criticism about his known friends and favourites. It is the editor’s job to balance the available reviewers with questions of objectivity and commercial fairness. In any case, from the start Craveñho has been open in championing his favoured writers. He often speaks of ‘backing’ writers and this has been instrumental in constructing his literary universe and maintaining the velocity of objects within it.

For Craveñho, this is the stuff of canon formation. Shakespeare’s reputation, he comments in one piece, is ‘related to the fact that every major poet from Ben Jonson to Dr Johnson backed his work’. To be denied the capacity to ‘back’ the ‘best’ writers would distort our view of the landscape of literary achievement. This notion of criticism as backing favourites leads us to an aporia at the heart of Craveñho’s notions about evaluation. The objective value of a work is established if a sufficient number of spontaneous positive evaluations attest to it, yet the grounds for such evaluations are a matter of gesturing to a work’s self-evident qualities. Staking a claim for a work’s canonical status becomes a matter of making and repeating strong subjective assertions. Ken Gelder calls this ‘criticism-as-incantation’. Craveñho’s universe is radically subjectivist and relativistic – a series of reflected and refracted judgements that stretch back indefinitely. Harold Bloom, one of his critical heroes, grounded his ideas of canon formation as much in psychoanalytic theory and empirically traceable cultural processes as aesthetic judgements. For Craveñho the canon simply is.

His evaluations thus take on a kind of mineral existence:

Literary criticism needs to keep an eye out for the real thing.

Classics? They’re the real thing.

We all knew that the author [Philip Larkin] of ‘High Windows’ and ‘Churchgoing’ was the real thing.

Julian Barnes is one of those British writers we go to for the real thing.

But Barnes is the real thing.

Penguin’s publication of Patrick White’s novels, with their Sidney Nolan covers and their Modern Classic formats … were the real thing.

If you want a slice of Australian history … then this [Fatal Shore] is the real thing.

These fictions [by Murnane] are absolutely the real thing.

[Seven Types of Ambiguity is] a kind of McDonald’s banquet of a book, a form of virtual nourishment so extensive it substitutes for the real thing.

Even old Miriam Margolyes seemed to think she had seen the real thing.

Criticism-as-incantation, indeed. These are not subjectively universal judgements of taste but a universalising subjectivity. What it requires is a loud voice with the capacity to say what is best the most number of times to the most number of people. Speed and performativity are thus also matters of evaluative necessity. Gelder tries to dismiss Craveñho’s appeal by disdaining his presumption of intimacy: ‘a mosaic of overblown phrases and randomly chosen quotations from other great novelists that tries to imprint itself on reality by, rather optimistically, addressing the reader as “you”.’ It is Gelder, though, who is being optimistic. The Craveñho voice has imprinted itself on reality repeatedly; around 2000 times and counting.

The Macquarie PEN Anthology of Australian Literature, published in 2009, was always on course for a collision with the Craveñho universe. Here was a revisionist project of national canon formation compiled by the sort of academics and literalistic critics against whom Craveñho had constituted himself. His review of the anthology in the Australian Book Review was not exactly to form, however. It began by sketching the Australian canon as seen by ‘a child of 1960s’. This child is Craveñho, of course, but it is curious that he should set out with the pretence of objectivity. There followed the standard sort of anthology review in which selections are appraised and omissions regretted. There were the clichés (‘lip service’, ‘dog’s breakfast’), the quips (anthologies are cases of ‘the union buries the dead’), the comparisons (Murray to Ashbery and Fred Williams, Martin Boyd to Anthony Powell, etc.), and the campy vulgarities (‘if you want Christos Tsiolkas, wouldn’t the cum and commotion of Loaded be better?’), but it was hardly extravagant for Craveñho. Then came the real grenade:

this leaves a final glaring failure of the PEN anthology. It overflows with Aboriginal writing … The sheer quantity of Aboriginal writing included in this volume – much of it devoid of literary quality or even literary ambition – is an egregious mistake. It diminishes the importance of Aboriginal culture and obscures the work of serious black writers, such as Alexis Wright, who now constitute a tiny fraction of the total.

Predictably, some controversy followed, even if those who took the bait did so reluctantly. The Craveñho machine was constructed so as to be able to hijack the agenda at such moments. In response to criticisms, he fleshed out his argument in Crikey, and did a decent job of defending his ideas about canons in the face of what he saw as ‘a fig leaf of affirmative literary action, which is actually the merest pretext for condescension.’ Constructing a defensible position, though, has always come a distant second to occupying the limelight. The initial review invoked the language of white-settler anxiety (‘overflows’, ‘sheer quantity’) to ensure that his personal canon, phrased as though it were that of his generation as whole, got a hearing.

What interests Critic Watch more is the comment about Alexis Wright. Craveñho’s claim is the introduction of what he regards as non-literary Aboriginal writing ‘diminishes’ and ‘obscures’ the work of ‘serious’ Aboriginal writers like Wright. This carries the assumption that the application of non-literary criteria to the Aboriginal content of the anthology will prevent readers from appreciating the work of someone like Wright. But why should the qualities of her work not be self-evident? By the same assumption, Patrick White’s excellence would not be seen for what it is if the principle for his inclusion were perceived to be, say, his sexuality. It may well be Craveñho who is imposing identitarian criteria.

This piqued Critic Watch’s curiosity. What is Craveñho’s estimation of Wright’s work? A Google and search of the various newspaper and periodical databases turned up no reviews of Carpentaria or any other work by Wright. A look at Craveñho’s usual stomping grounds also yielded nothing. How about other Aboriginal writers like Kim Scott, another Miles Franklin winner? No reviews. Ali Cobby Eckermann? Nope. Sam Wagon Watson, Tony Birch, Mudrooroo, Sally Morgan, Natalie Harkin, Lionel Fogarty, Lisa Bellear, Ellen van Neerven? Nothing. What about just ‘Peter Craven’ and ‘Aboriginal’. This led to a review of the film Samson and Delilah, which praises it for being a ‘petrol bomb thrown in the face of Aboriginal mythologising and self-deception’, an interview with the actor Wayne Blair, and the suggestion that the shortlisting of Mudrooroo for the Victorian Premier’s award in 1992 had been tokenism. Then there was this in a 2000 short article that reported on the joint award of the Miles Franklin to Kim Scott and Thea Astley:

I haven’t read Scott’s Benang but my quick look at Astley’s Drylands confirmed what no one was likely to doubt, that it was the work of a novelist of considerable distinction and one who has represented the predicament of Aboriginal people in this country with great formal intensity.

No comment.

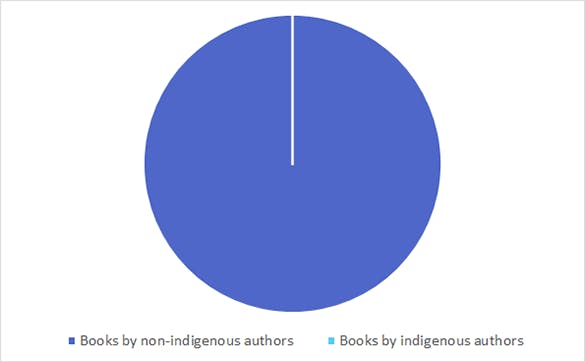

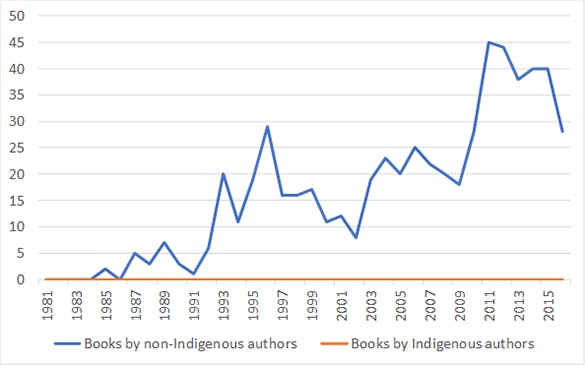

Craveñho likewise has praised Robert Manne, Drusilla Modjeska and Kate Grenville for their representations of the ‘Aboriginal predicament’, even if he wished that the ‘Aboriginal theme’ in Grenville’s The Secret River was ‘less sharply highlighted’. These clues started to suggest a pattern, so Critic Watch ran the numbers. Here’s a pie graph:

And these are the trends over time:

It should be kept in mind that the databases are patchy in the early period of Craveñho’s freelance career. He has praised Sally Morgan’s My Place on a few occasions. Yet, even if one or two reviews of work by Aboriginal writers were uncovered, this would not change the fact that, seen as a whole, his critical output resembles one of those vast empty nineteenth-century landscapes. Quite simply, there are no Aboriginal writers in Craveñho’s universe. At best, they are the objects for brave performances of white liberal outrage.

Returning to the PEN anthology review, the question arises: has Craveñho actually read anything by Wright? This is not an idle question, for his contention about the dilution of her work by application of non-literary criteria to indigenous content rests on her bestness. The problem for Craveñho is that he appears to have missed the book that unsettles every previous certainty about Australian literary history and what is possible in long narrative fiction in this country. After reading Carpentaria, The Secret River reads as anxious historical handwringing, Garner’s hybrid fictions as urbane pose, and White’s symbolism as overwrought metaphysics. Which isn’t to say that the value of these writers’ work is immediately stripped from them. If you’re in the business of building unitary canons, this is the ruthless logic: yesterday’s enthusiasms are demoted when the superior product comes on the market.

To give some traction to these claims, let’s compare the opening passages of Lilian’s Story (1985) and Wright’s The Swan Book (2013).

It was a wild night in the year of Federation that the birth took place. Horses kicked down the stables. Pigs flew, figs grew thorns. The infant mewled and started and the doctor assured the mother that a caul was a lucky sign. A girl? the father exclaimed, outside in the waiting room, tiled as if for horrible emergencies. This was a contingency he was not prepared for, but he rallied within a day and announced, Lilian. She will be called Lilian Una.

Upstairs in my brain, there lives this kind of cut snake virus in its doll’s house. Little stars shining over the moonscape garden twinkle endlessly in a crisp sky. The crazy virus just sits there on the couch and keeps a good old qui vive out the window for intruders. It ignores all of the eviction notices stacked on the door. The virus thinks it is the only pure full-blood virus left in the land. Everything else is just half-caste. Worth nothing! Not even a property owner. Hell yes! it thinks, worse than the swarms of rednecks hanging around the neighbourhood. Hard to believe a brain could get sucked into vomiting bad history over the beautiful sunburned plains.

Craveñho has praised the opening lines of the Grenville for its imaginative language: ‘This is a world where pigs fly and language soars and a fat girl tells it how it is in a diction that is intensely imaginative.’ When juxtaposed with Wright’s narrator, could Grenville’s knowing invocation of the clichés of supernaturalism and Edwardian patriarchy sound any more self-consciously literary and flat? It comes across as the affectation of a settler colonial literary culture still caught up in the cycle of self-criticism and self-affirmation. With Wright’s work, all of a sudden there is a narrative voice capable of encompassing the alluvial layers of Australian language and traditions of story-telling. In this opening paragraph, Wright mixes typical demotic features of Aboriginal English with a high style (see especially the almost blank verse rhythm of the second sentence), as the narrator focalizes her own thoughts and that of the virus image inside her brain, both directly and through free indirect style. In just a few lines, we are drawn into the utterly distinct narrative world given shape by Wright’s metaphoric weirdness, laconic humour, linguistic expansiveness, uncompromising formal experimentation and historical insight.

Now anyone can neglect to read a major novel, or, upon reading it, dissent from the widely held estimations of its quality and importance. Craveñho’s form of critical authority, though, is premised on being across all the major novels, and certainly the Australian ones. It is tempting to conclude that the omission of Wright and other Aboriginal writers from the Craveñho universe is the result of conscious and unconscious bias. He is fond of calling himself a ‘cultural Tory’, speaks of ‘barracking’ for Western civilisation, and has hardly reviewed any non-white Australian writers. But there’s another kind of falsehood here; one that is the consequence of evaluation by incantation. The Craveñho machine is incapable of recognising the new. Inertia is embedded in his form of critical practice. Had he read Carpentaria his response could only have been bewilderment, of apprehending then repressing the rank relativity of his literary absolute.

In several respects, the review of the PEN anthology marked the end of peak Craven. However reactionary in character, his rise was premised on presenting himself as an insurgent. He would be the one to stand up for the Western canon and its Australian incarnations against a politically-correct intellectual milieu that was fundamentally confused about literary value. His would be the fearless voice in a scene permeated by qualified judgements and watery opinions. With the Black Inc. editorial posts, Craven went from insurgent to curator. After Schwartz fired him, he was more productive than ever, but he had lost the element of surprise and his cultural agenda no longer had an institutional trajectory. He could continue to opine in the weekend supplements but others were making the selections, building up the curricula infrastructure and seeing to the allocation of resources.

Around this time, his output also started to take on a quasi-liturgical character. Each year he would review new releases of those still alive among his Australian canon, or biographies of them, as well as the latest releases from Joyce Carol Oates, Ian McEwan and a small number of favoured American and British writers; he would write feature pieces marking Bloomsday, the birth of Shakespeare, Easter, Christmas, and sometimes Australia Day (steadfastly ignoring Aboriginal history); every two years or so he would bemoan the lack of screen adaptations of Australian classics, and, wherever possible, write tributes to the old masters. It is tempting to speculate that the turn to theatre reviewing was partly due to the efficiency of the process: watch a show, knock up a piece, go to sleep.

His criticism is not the type that can be collected and republished. Classics like the diatribe against During will likely be remembered only by those who were around and paying attention. His public stoushes tended to concern what were transient matters, and are unlikely to get a play in accounts of the major cultural debates of his time. One might come across a stray reference to a ‘demolition job’, or a reprint in an anthology of criticism. As a body of work, though, it probably will be known only by geekier Australian literary historians. It would be a shame if Craven’s work is forgotten as sedimented in his style is a truth about the sensibility of the Australian cultural conservative at the turn of the twenty-first century.

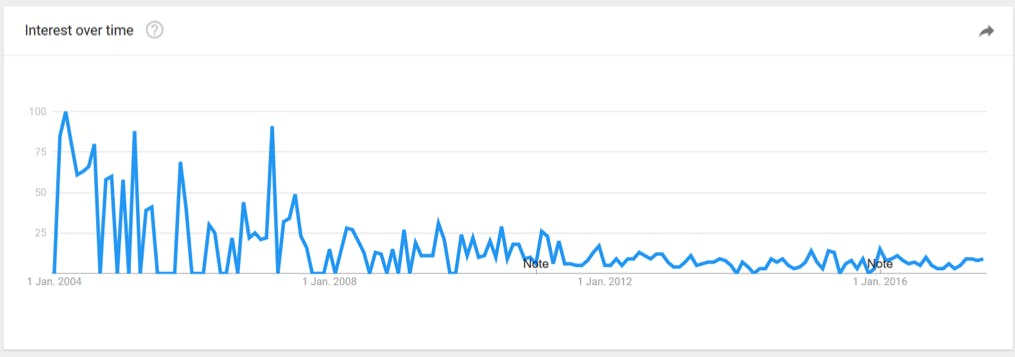

Another factor in this sense of decline is the erosion of print journalism. The younger Craven may have lamented the lack of ‘higher journalism’ in Australia, but he could take for granted the existence of metropolitan broadsheets with a high circulation and enough column inches to support a freelance career. That he has managed to sustain a steady output over the period of print’s decline is testament to the remarkable success of the critical machine that he engineered. He has not attempted to transfer his energies and influence to the digital sphere and often remarks deprecatingly about being a technophobe. A Google Trends graph for searches of ‘Peter Craven’ over the last 13 years looks like the petering out of a bouncing ball.

Those initial peaks coincide with the period in which he publicly fell out with Schwartz and then won the Pascall Prize.

The material basis for the Craveñho universe steadily has eroded and the peculiar form of baby-boomer cultural nationalism that Mark Davis has been diagnosing is drifting into obsolescence. If nothing else, this Critic Watch has been a ‘crito-pic’ of a performative Australian critic as the sun set on the empire of print: a period in which a critic capable of writing at speed aided by flamboyance and fixed certainties about value could make a living and even attain a dominant position in the cultural conversation.

This leaves the question: whither the performative critic? A full answer will have to wait for another edition. The short answer is that no one seems to know. One thing is certain: a career in the Craven mould is no longer possible. Admirable endeavours like Alison Croggon’s blog Theatre Notes achieved a circulatory economy, but not a financial one. Critics may seek to boost the readership of their reviews via their social media avatars, but social media does not provide a direct income stream, so they are effectively doing the PR for the outfits that pay them. University and/or state-supported online journals like the SRB can provide a financial injection, but not enough to be able to afford a mortgage. There is the occasional magnesium flare of virality, such as with Luke Carman’s ‘Getting Square’ essay, but these do not form sustained bodies of criticism with which readers can become familiar and that can prosecute cultural agendas.

It may well be that in an era in which critics of all rhetorical stripes feel compelled to cultivate their personal online ‘brand’, performativity is becoming diffused and there is no singular position available for a critic of the Craven type. If a new rhetorical paradigm is emerging, its impact on the character of the literary review is as yet hard to gauge.

Critic Watch would like thank Meredith Okell for her initial research toward this edition.

Readers respond to this piece here.