we turn into a side street, turn again

into a lane, then

down a short dead end

to where rusted tin, a black cat and red wheel

barrow wait for us below a peeling date palm.

– Kevin Brophy, ‘Walking,’

Our work is made possible through the support of the following organisations:

Prithvi Varatharajan on soundwalking

Please be aware that this essay contains the names of Aboriginal people who have passed away.

In October 2017 I led twenty people around the inner-Melbourne suburb of Brunswick. It was a guided walk, but unlike any most in the group had experienced before. Mine was one of five walks in a public arts project aimed to facilitate aural attentiveness to our environment. Walking Brunswick was sponsored by Moreland City Council1 (which spans fifteen suburbs including Brunswick, across a tract of land in the inner-north of Naarm/Melbourne), the experimental music collective Avant Whatever, and the Australian Forum for Acoustic Ecology (AFAE). Three artists including myself were invited to participate in the project by Anthony Magen – landscape architect, soundwalker, and a member of the AFAE – and Dr Ben Byrne, experimental musician and media scholar. Our brief was to allow our individual arts to inflect each of our soundwalks; I was invited as a poet.

we turn into a side street, turn again

into a lane, then

down a short dead end

to where rusted tin, a black cat and red wheel

barrow wait for us below a peeling date palm.

– Kevin Brophy, ‘Walking,’

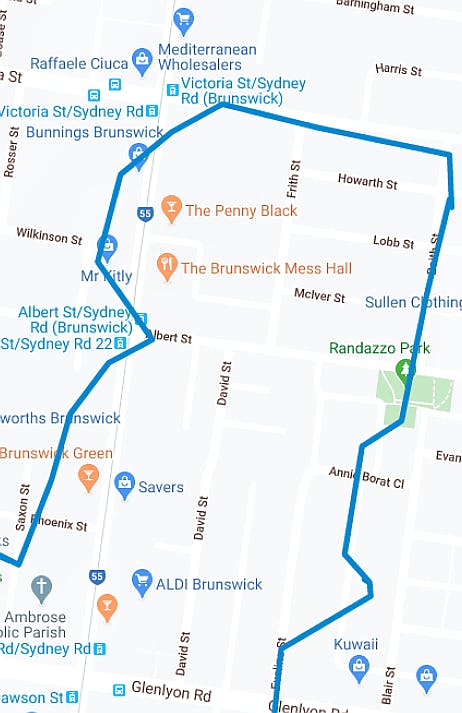

My group of soundwalkers crossing Sydney Road at Victoria Street in Brunswick.

The first soundwalk I attended – devised by Magen in Sydney, as part of the Voice Presence Absence conference at the University of Technology in 2013 – was revelatory to me. It gave me a deep feeling of connection to place, that I registered through my ears, my feet, and my skin, and a deeper understanding of urban geography. Until this event I hadn’t realised that a few blocks of city space were so porous, with as many ways of being traversed as minutes in a day. Certain aural and visual impressions from that soundwalk have stratified as memory. These have to do with other people’s perceptions of our activity: a pedestrian walking in the opposite direction, visibly alarmed by the spectacle of a dozen people ambling – seemingly without purpose – down an empty alleyway in Ultimo; a bartender’s expression of bafflement at our streaming through his bar, from the back entrance to the front, silently and in single file (wryly: ‘buy a drink at least!’). People commonly react with surprise, amusement, or vague disquiet when they witness a soundwalk. Though superficial to the walk itself, these encounters in urban space are memorable, adding as they do to its ability to reset geographical familiarities, to lend us the experience of children feeling out their environment – of their bodies in their environment – for the first time.

I’ve been on several more soundwalks in inner-Melbourne, with Magen as guide, and I’ve noticed how he frames the act of walking intentionally as redolent with history: the pre-colonial and colonial history of the land. By asking us to be attentive to the sound of our environment, and by stating that we are not the first to do this – that the Wurundjeri have walked this land for thousands of years, and continue to do so – he also seeds an awareness of historical-acoustical traces. I’ve often thought of what it means to be a member of a Forum for Acoustic Ecology. For reasons known only to my unconscious, I initially confused ecology with conservation in this particular title. But its members aren’t preventing sounds from dying out: rather they’re listening for the total web of inter-related sounds in an environment – and marking shifts in that soundscape over time.

When you take your ears for a soundwalk, you are both audience and performer in a concert of sound that occurs continually around you. By walking you are able to enter into a conversation with the landscape.

– Schafer, Vancouver Soundscape

These were the ingredients of the walk I devised: a carefully mapped slow journey around a section of southern Brunswick centred around Sydney Road, at 12 pm on a late-spring day, starting at the Wilson Street public space and ending on the corner of Edward and Charles Streets; a party of walkers; and poems by Ella O’Keefe, Kevin Brophy, Bonny Cassidy, Lisa Bellear, Gig Ryan, Tim Wright, and myself which I read at planned spots along the route. My method was to choose work by Brunswick poets – those who had lived in the area for years, and whose poems, I thought, would enrich our experience of the place. I hoped, too, that the location I chose to read each poem would give it new sensory and hermeneutic resonances – cast it in a new light, to use a familiar visual metaphor. My route featured sonic contrasts: the jostle of sounds on Sydney Road; bird calls in alleyways; the regular music of the train line; commercial sounds encroaching on residential zones; the sounds of interiors and exteriors (at one point I walked the group through a Bunnings Warehouse, with its ubiquitous concrete floors sharpening the sound of cash registers, hard and shuffling footsteps, pop songs at low volume, and sliding automatic doors). My addition of poems was an adaptation of the classic soundwalk, which the following notes may help to define:

1. R. Murray Schafer coined the term ‘soundwalk’ in the 1970s, in the context of his World Soundscape Project (WSP) at Simon Fraser University in Canada. He defined a soundscape as ‘any acoustic field of study. We may speak of a musical composition as a soundscape, or a radio program as a soundscape or an acoustic environment as a soundscape. We can isolate an acoustic environment as a field of study just as we can study the characteristics of a given landscape.’ In thinking about soundwalking he distinguished between ‘listening walks’ that occur more or less in a straight line with no intervention, and the composed soundwalk, which is:

An exploration of the soundscape of a given area using a score as a guide. The score consists of a map, drawing the listener’s attention to unusual sounds and ambiances to be heard along the way. A soundwalk might also contain ear training exercises. For instance, the pitches of different cash registers or the duration of different telephone bells could be compared. (The Soundscape)

Hildegard Westerkamp – composer, musician, and an important member of the WSP – contributed in 1974 to the proliferation of the practice. She did so by defining soundwalking less strictly as ‘any excursion whose main purpose is listening to the environment’. She described various ways a soundwalk might be devised: for example, with one sighted person leading a blindfolded person; in small groups, which could explore ‘the interplay between group listening and individual listening by alternating between walking at a distance from or right in the middle of the group’; and by modifying the size of the geographical area covered.

2. In a common form of the soundwalk, the party maintain verbal silence throughout the walk, so that they hear only the environment, and their bodies in the environment: footsteps, the rustle of clothing, inhalations and exhalations. The pace is very slow to facilitate prolonged listening, meaning the walkers are out of step with other pedestrians.

3. Soundwalks make us attentive to sound by de-familiarising our environment. John Levack Drever writes:

One of the underpinning goals of soundwalking is … circumnavigating habituation, in a process of de-sensitization and consequently re-sensitization, in order to catch a glimpse (un coup d'oreille) of the ‘invisible, silent and unspoken’ of the everyday.

Note the use of visual metaphors – ‘catch a glimpse’, ‘invisible’ – to describe attentiveness to the aural. Once you become aware of the language of sensation, you notice the predominance of the visual in our language: to comprehend something is to ‘see it clearly’, for instance. Walter Benjamin, drawing on Georg Simmel, noted that large cities – such as the nineteenth-century Paris of his Arcades Project – were characterised ‘by a marked preponderance of the activity of the eye over the activity of the ear’. The soundwalk attempts to reverse this programmed not-hearing; in doing so it disrupts our mind’s intuitive classification of sounds as meaningful (the human voice or car horns at close range, shouts from afar, pedestrian and train crossing bells), or meaningless (the continual swoosh of transport, car horns at a distance, indistinct voices, wind, bird calls in the midst of traffic). All sounds become available to our ears and we may savour them, think about their significance or insignificance, their presence or relative absence.

4. Iterations of a particular soundwalk are unique, as the soundscape of an environment is constantly changing, its animal and human population always fluctuating – not to mention that the same sounds feel different depending on the climatic condition and time of day.

There are long-standing literary traditions of walking – and writing about place – that intersect with soundwalking. Drever, in ‘Sound Walking: Aural Excursions into the Everyday’, describes a precursor in Romantic artists’ explorations of the countryside:

Aristotle and his school, the Peripatetics … were said to have conducted their lectures on foot, pacing up and down the colonnade: an account without solid foundations, yet from the eighteenth century, a revered practice that pervaded nineteenth- and twentieth-century thought. It feeds into the cult of the pastoral idyll and the metaphysical figure of the lone artist tackling vast landscapes that propel the individual into the sublime; this is the era of the romantic ecologists Wordsworth and Coleridge.

For the Greek poet and academic Bill Psarras, modern art practices that soundwalking emerged from encompass ‘the 19th century flâneur as the romanticised observer of the emerging urban modernity … Dada excursions (1910s) … Surrealists’ oneiric wanderings (1920-1930), [and] Situationist International’s (1957) radical method of psychogeography’. All these belong to a European tradition, whereas the location of my walk was within the continent of ‘Australia’ – a name based on the Ancient Greek and Roman notion of ‘Terra Australis Incognita’, a gigantic landmass that was speculated to exist in the south. While Antarctica is closer to the imagined size of such a continent, from the 16th century onwards variants of ‘Terra Australis’ were attached to our continent by Portuguese, Dutch, and British geographers and navigators, and reflected on their maps. But ‘Australia’ and Naarm have a distinct, Aboriginal history, spanning 65,000 years or more. If we think of the soundwalk as a form of intentional walking, then Walking Brunswick has resonances in local history, in Aboriginal peoples’ journeying across Birrarung (the Yarra River), the Merri Merri, and Naarm, long before Brunswick existed as an urban settlement. In my soundwalk I offered impressions of such history by reading certain poems. These readings gave us a chance to think about the poems’ subjects in relation to the location of their audition (‘are there significant historical resonances between this poem and this place, or otherwise, is this a meaningful aural-spatial juxtaposition?’ I imagined the audience asking themselves). I did not wish to dictate but to imply. In certain instances explored below, the symbolism of a cultural institution at the site of my reading – in concert with abundant, technologically-produced sound, which incessantly evoked the urban present – made the relationship between past and present, as we sensed it in that moment, more palpable.

I would suggest that a locally pertinent context for soundwalking lies in the Aboriginal practice of singing Country, and in their use of songlines over thousands of years. I do not mean to position the soundwalk with poems as comparable to the songline: the former is a relatively recent Western art practice focused largely on urban environments, and in this respect is worlds apart from the latter. People walked Country intentionally however – paying sensory attention to place – thousands of years before Europeans arrived (and long before the European-influenced World Soundscape Project of the late 1960s, and its later transposition to Australia), and I refer to the songline in that sense.

A recent account of ‘songspirals’ (preferred by the authors over the terms songlines and song cycles) is offered by the Gay’wu Group of Women, from Yolŋu Country in North East Arnhem Land: ‘They are a line within a cycle. They are infinite … Our songs are not a straight line. They do not move in one direction through time and space’. They go on:

Songspirals are all about knowing Country, where the homelands are, the essence of the land and water and sky. They map the land but in a different way, a deep mapping … The songspirals locate a place, locate Country, and they take us there. They connect us to that Country and to the person who was there and has passed away, to the ancestors and to those yet to come, and they connect that Country to other Countries, to other clan homelands around it, in a great pattern of co-becoming and co-emergence. Through songspirals, we know where we are and we know who we are.

We weave together our connections between space, the earth and the journey of the spirit. There is always a process, a way of going through the right process of negotiation. This is negotiating and renegotiating relationships between clans and their responsibilities as part of the songspiral … The weather, the stars, the winds, they connect … The wind here is connected with the sky. When the wind blows from the north, yams are growing. We learn by when the wind blows what is edible.

In Song Spirals: Sharing Women’s Wisdom of Country Through Songlines, a detailed picture emerges of interrelations between singer, land-affiliation, clan-affiliation, and the current and afterlife of the spirit – one that suggests a much more complicated engagement with place than accounts of songlines as storied maps of landscape. This conception is also specific to their Country and culture: the Gay’wu Group of Women refer throughout to ‘milkarri,’ which are ‘songspirals as cried and keened by women’, elsewhere defined as ‘an ancient song, an ancient poem, a map, a ceremony and a guide’. By contrast, John Bradley together with Yanyuwa families on the Gulf of Carpentaria refer to the Yanyuwa concept of ‘kujika’ as: ‘Song line, song cycle, songs of power that are embedded in the earth and are thought still to be coursing through the earth. Yanyuwa men give voice to these songs’.

These cultural forms intersect with the colonial history of Brunswick. The Melbourne-based historian Jim Poulter – whose forebears settled in Wurundjeri Country in the 1840s and sought to learn their history – has written about the role that songlines played in John Batman’s journey to meet the Wurundjeri at present-day Heidelberg, in June 1835. Batman acted as a representative of the Port Phillip Association, a private group of landowners from Van Diemen’s Land who thirsted after a settlement at Port Phillip, or present-day Melbourne. Having allegedly signed a treaty with the Wadawarrung at Indented Head, for 100,000 acres around Geelong, Batman journeyed north in pursuit of a second treaty, for 500,000 acres around present-day Melbourne.

Poulter states that the songline is where ‘geographic markers and land features along the route are coded into a song which are sung as you travel along to remind you of when and where to deviate’, and that:

Most often these Songlines follow ridge-lines, valley lines and easy contours, as well as connecting between river fords and creek confluences. To Batman’s Sydney guides it was like having neon signs telling them where to go. Batman’s Sydney men were also well aware of the protocols that governed the use of Songlines ... they would therefore have followed the proper protocol by ‘Singing Country’ as they went along. At its simplest level this involves singing in praise of the geographic features and landscape you see as you walk along, thus announcing your peaceful intentions to the local tribe.

Following the initial meeting with Wurundjeri at Heidelberg, Batman obtained the signatures of eight ngurungaeta or clan headmen of the Kulin nation, from the Woiwurrung and Boon Wurrung peoples – including Bebejan, Billibellary, Bungarie, and Jagga-Jagga – on 6 June 1835. As Poulter notes, he had with him several Koori guides from Sydney acting as intermediaries (Port Phillip District, surrounded by present-day Melbourne, was part of the colony of New South Wales until Separation in 1851; Batman had travelled from Sydney to Van Diemen’s Land, then to Port Phillip). The ‘trade’ recorded by the treaty is remarkable; a transcription of it is accessible in Shirley Weincke’s When the Wattles Bloom Again: The Life and Times of William Barak. In return for 500,000 acres, the treaty stipulates that Batman pay the Kulin: ‘Twenty Pairs of Blankets, Thirty Tomahawks, One Hundred Knives, Fifty Pairs Scissors, Thirty Looking-Glasses, Two Hundred Handkerchiefs, and One Hundred Pounds of Flour, and Six Shirts’. It also stipulates that yearly rent be paid to the Kulin and their descendants, of: ‘One Hundred Pairs of Blankets, One Hundred Knives, One Hundred Tomahawks, Fifty Suits of Clothing, Fifty Looking-Glasses, Fifty Pairs of Scissors and Five Tons of Flour’. The validity of the treaty (and the notion that the Kulin understood Batman’s intent to take permanent ownership of the land, when there was no common language between them) has been widely disputed.

Drawing on Batman’s journal, historians have argued that the Merri Creek, at the southeast edge of present-day Brunswick East, was the most likely meeting place for this treaty signing – the other two possible locations being further north at Darebin Creek or the Plenty River. However, all of Batman’s documentation – the treaty, the entries showing his routes and dates – may have been calculated deceptions, ‘a ruse to cheat Aboriginal people out of their land’ as Thomas James Rogers notes, citing a common view in the treaty’s historiography. Batman had also previously murdered scores of Aboriginal people unprovoked, in Van Diemen’s Land, as Ben Kiernan records in his global history of genocide – a fact that surely casts shadow on notions of his dealing with the Kulin as sincere or fair.

Poulter therefore prefers Wurundjeri-willam Elder William Barak’s transcribed testimony of the event; he was present at the treaty signing, aged eleven:

We know from Barak’s narrative that the treaty meeting took place on Muddy Creek, the Woiwurung word for which is Kurrum, or more exactly, Kurrum Yallock. Darebin in Woiworung refers to a bird, the Welcome Swallow, which is a harbinger of Spring when it returns from wintering in northern Australia. Merri on the other hand means rocky and Merri-Merri means very rocky. Anyone looking at the Merri Creek can tell you that the name is very apt. Darebin Creek is similarly very rocky and neither the Merri nor Darebin Creeks fit Batman’s idyllic description of the meeting place as being beside ‘a beautiful stream of water.’

He suggests the Plenty River in present-day Greensborough – much further northeast – as the likely place of the treaty signing. Nevertheless, the southeast pocket of East Brunswick at Merri Creek remains infused with the story of the treaty signing, and all its connotations of colonisation, deception, violence, and rupture of culture and Country. This is not to downplay the fact – which Emily Fitzgerald and Daniel Ducrou highlight – that ‘to this day, Batman’s treaty is the only land-use agreement that has sought to recognise European occupation of Australia, and pre-existing Aboriginal rights to the land’. The treaty was nullified by the Governor of New South Wales, Richard Bourke, three months after it was signed, using the doctrine of so-called ‘Terra Nullius’.

This is a significant historical context for my intentional walking of Brunswick, which I sought to evoke in the walk by reading Lisa Bellear’s poems ‘Mr Prime Minister (of Australia)’ and ‘Beautiful Yuroke Red River Gum’. Bellear (1961-2006) was born, and died, in Melbourne. She was a Minjungbul/Goernpil/Noonuccal/Kanak woman, an executive member of the Black Women’s Action in Education Foundation, an activist, and for eleven years a presenter on the Not Another Koorie Show on 3CR community radio. Though she was a long-term resident of St Kilda, she partly wrote Dreaming in Urban Areas (1996) from Brunswick. Here is her poem ‘Beautiful Yuroke Red River Gum’:

Sometimes the red river gums rustled

in the beginning of colonisation when

Wurundjeri,

Bunnerong,

Wathauring

and other Kulin nations

sang and danced

and

laughed

aloud

Not too long and there are

fewer red river gums, the

Yarra Yarra tribe’s blood becomes

the river’s rich red clay

There are maybe two red river gums

A scarred tree which overlooks the

Melbourne Cricket Ground the

survivors of genocide watch

and camp out, live, breathe in various

parks ‘round Fitzroy and down

town

cosmopolitan

St Kilda

And some of us mob have graduated

from Koori Kollij, Preston TAFE,

the Melbin Yewni

Red river gums are replaced

by plane trees from England

and still

the survivors

watch.

I read this powerful poem on the lawns outside Blak Dot, an Indigenous-run art gallery nestled next to the Upfield train line, near the Brunswick Baths. The following lines come from another Bellear poem I read at that location, ‘Mr Prime Minister (of Australia)’, written in Varuna and dated June 1993. The poem is addressed to Paul Keating, and seeks to name the trauma that festered even as Australia began thinking of freeing itself from Britain:

Unfortunately Australia is immature. Even the talk of

‘Republicanism’ is rather immature while there is continual

denial that this country is Aboriginal Land.

I’ll be honest with you, I am frightened, racism is a disease;

do you ever wonder what manifests from diseases that

haven’t received adequate treatment, say for over 200 years.

The poem combines moods of sadness, anger, sarcasm, and comradery. Parts of it are wryly humorous, such as at the beginning: ‘Dear Mr Keating, / Hi there, it snowed today, up in the Blue Mountains. I’ll / never complain about Melbourne weather again’. It ends in a tone of earnest conciliation: ‘If you need support, like to talk. / Yours Sincerely, / A. Citizen / (Noonuccal)’. All of the soundwalks in Walking Brunswick conveyed that our journeying occurred on land with a history of purposeful walking, speaking, and singing before European invasion. While others referred to this in their prefatory comments, I sought to convey it through my reading of these poems – an Acknowledgement of Country through verse.

An aural collage of soundscapes in the walk: a wind tunnel near a Woolworths carpark / birds, dogs, and children / our rhythmic descent from the train line footbridge / Sydney Road ambience / pedestrian crossing bells / walking through Bunnings to the main road / motorbikes gusting past / an alleyway with bird chirps and a droning plane.

What exactly happens – to a poem and to a place – when you add poetry to a soundwalk, selecting complementary ingredients: this poem goes with that location / this word goes with that sound? Some poems I read referred directly to a history linked to the place we stood on, such as Bellear’s poems, or Brophy’s ‘Walking,’. I read the latter, with its account of a journey on foot, at the exact spot described in it, at the base of a bridge just north of the train line at Dawson Street:

We walk to wooden steps above the rail track,

stand with broken glass, abandoned bottles

and strangely you bend low and reach out

like a priest or a scientist

towards thrown down cups and glass chips

to retrieve a perfect five dollar note.

The final lines of this poem jarred with the time of day I read it (noon): ‘Just behind Brunswick, as it always does, the old sun rolls / into that dark slot in the far horizon’. I offered a poem that was a near-perfect match to an idiosyncratic urban locale. To access that bridge coming along Dawson Street, you need to cross and walk by the train tracks, treading on rough gravel next to a nondescript corrugated iron fence that borders a police bus depot, with no barrier between you and passing trains. To get an even closer match to the environment, I could have read the poem at sunset, which would have been absurdly literal. The audience must have noted poetic referents in their surroundings, and may have noted the imperfect alignment been the two – in a way I hoped was mutually enriching. Though experienced as sound in my reading (and though allusions to sound feature in the poem, like in the ‘sparks and thuds’ as objects fall from a burning Brunswick warehouse), this poem appealed more to our visual perceptions.

Following ‘Walking,’ I walked up the stairs and stopped the group in the middle of the bridge, where we could not only see the train tracks in both directions, and hear the trains passing at close range, but where we also heard people splashing in water, their voices reverberating. This drew our eyes to the left facing south, to a prime view of the Brunswick Baths. It’s at this spot that I read Bonny Cassidy’s short poem ‘The hold,’ from her book certain fathoms (2012):

On the surface of the pool two lappers

have traced a diamond.

It stretches as they rest, oblivious

to the nearby tree

where a web is pegged

from bough to grass

its nub falling flush

on a knot in the trunk.

The web swallows the breeze and swells

capilee, capilash,

one of the swimmers

crosses back

Cassidy lived in Brunswick for several years. I don’t know if she drew on the Brunswick Baths in her poem; it could have been wholly imagined, or inspired by any swimming pool. But the image of the Baths, viewed from the railway footbridge, is stunning. The view is of undulating blues and whites of water; vibrant colours of swimwear; a faded mural painted by Bob Clutterbuck and Pam Ingram, depicting Brunswick’s twentieth-century history; and earthy brick. Arresting too are the sounds of splashing, and of human voices bouncing off the water and the walls of the Baths before travelling beyond. Cassidy’s poem combines aesthetically striking images and sounds, in similar proportions. ‘The hold’ has a preoccupation with geometric and natural patterns: the diamond traced by the swimmers and the pattern of a spider’s web viewed against a knot in a tree trunk. Read as part of the walk, I liked the way the poem ended in sound, with ‘capilee, capilash’ onomatopoeically evoking water play – and also how the first and last stanzas seemed to mirror the ordered leisure we saw before us. I intended the visual/aural harmony in the poem to meet that of our environment.

Reading Ella O’Keefe’s ‘Runcible’.

Other poems asked the audience to focus on intersections between urban and poetic sound. Ella O’Keefe’s ‘Runcible’, which I read in an alleyway with a view of a community vegetable garden, adjacent to a bar/club called Howler, is a sound poem that revels in the acoustics of language:

honey pot sweet bunny data honey

data sweet goddette pocket bunny cut

turtle dove giga pot mattock sweet

The slight acoustic tunnel created by the alleyway outside Howler, which punctuated my reading with its thumps of bass – and over the top of which suddenly came the ricocheting shots of a nail gun – seemed perfect. This was the first poem I read on the walk, in order to focus participants’ attention on sound: on language as sound, on intersections between linguistic and non-linguistic sound. It was a way of asking participants unfamiliar with both soundwalking and poetry, but whom I thought may have preconceptions of poetry as transcendental speech and/or emotional expression, to experience the poem foremost as sound – and to use it as a model for listening. The poem ends with noticeable aural repetitions, some hard consonant sounds, and a final, open-sounding vowel:

mattock goddette cut dove turtle pet

open cut pet honey pocket giga

In preparing for my soundwalk I listened closely to the streets of Brunswick, walking them at different times of day, on my own and with Magen and Byrne showing me parts of the suburb they knew intimately; I listened to the sound of the place while thinking of poems; I looped in and out, back and forth, until a possible one-hour route formed in my mind; and I read work by Brunswick poets until I was able to match a poem with a specific place within that route, six times over – one location per poet. I then drew the route over a map, and rehearsed the walk, testing it against the poems and vice-versa. This process is how I settled on reading the poem ‘Coburg Sound’ by Tim Wright, from his untitled 2017 chapbook (and reprinted in his book Suns) in a long cobblestone alleyway between the rear of several blocks of houses, running roughly north to south parallel to Sydney road on the eastern side. There was something about the absence of main road sounds (which we’d just experienced), and the feeling of being backstage – somewhere only an ‘insider’ might know and walk – that I thought spoke to the poem, or the way objects came to the speaker in the poem. Take these Coburg impressions (Coburg and Brunswick are adjacent suburbs, and Wright lives on their border):

Woolworths, light-gouged

through the carpark mist

(Moonee Ponds)

…

a few sundry handclaps, thankyou mumbled into the verse

the moon loose and cold, blunted, close; near

ultrafine rain

last swim in chrome

flakes of pepper, street-worn tables

‘Our famous weather’

In the middle of ‘Coburg Sound’ there is a comic allusion to local history, in how Coburg and its human and architectural residents are changing over time: ‘As butchers become florists . . . / ageing adolescents / rat tails gone wrong’. The poem contains more images than sounds, which may lead the reader to wonder about the titular reference. But there are sounds peppered throughout (handclaps, a thankyou), and they rush at you, wordily, at the end:

I glide thru traffic like a pin

extruded tramtrack tuning fork

drum-fill from a storage shed

the wide berth of the afternoon

Read aloud, I felt the ‘Coburg Sound’ was the poem itself: the sound of it reverberating in that alleyway, introducing referents from nearby suburbs (Moonee Ponds is also adjacent to Brunswick, on the west side). Its final line closed out the poems in the walk, and seemed to suggest the unfolding possibilities of the afternoon, as we ambled to our destination near the Charles Weston Hotel, once known as the Sporting Club Hotel. From 2015 to 2017 this pub hosted the Sporting Poets reading series founded and curated by Cassidy, featuring local and interstate readers; afterwards the reading kept its name but changed venue and curator (Alice Allan). This was part of my design of the walk: a final, unsounded allusion to recent poetic history and ongoing poetic practice.

In the discussion that occurred in the group afterwards, it seemed that many participants were new to both (Australian) poetry and to soundwalking, though there were also a few regular soundwalkers, and poets – including Wright, O’Keefe, and Cassidy – present. The discussion did not go long enough for me to gauge how my intent aligned with the effect. Palpable, though, was a sense of surprise – that the urban environment, and poetry, could be experienced this way. It reminded me that every time I’ve been on a soundwalk, whether in Melbourne or Sydney, I’ve felt profoundly surprised by an environment I thought of as familiar. Part of this surprise has to do with being shown parts of a suburb I didn’t know existed. Part of it has to do with the meditation induced by walking at a very slow pace while tuning wordlessly into the environment. Part of it has to do with discovering that it’s possible to endlessly renew your experience of the same location, by walking different listening routes.

A map of part of my soundwalk showing Annie Borat Close.

I re-walked the route of my soundwalk in November 2019, and I was struck by shifts in urban geography, as well as resonances I’d missed two years prior. I thought most about the Wurundjeri history of Brunswick on this walk, which I did on my own. Perhaps it was because of my reading on the subject in the intervening time that I noticed Annie Borat Close, running off the alley where I read ‘Coburg Sound’ by Wright and ‘Brunswick Falls’ by Ryan. Annie Borat was the younger sister of William Barak, and the daughter of Bebejan, one of the Wurundjeri ngurungaeta present at Batman’s treaty signing – a significant historical reference. On this street I found the Annie Borat Free Food Pantry, which a resident had set up in their front yard. The glass doors of the pantry declare, ‘Take what you need / Give when you can’, while its Facebook page says it was started on 10 February 2019 and is ‘for everyone – whether you’re homeless, food poor or just forgot the pasta sauce on the way home’. Adjacent to the pantry, in a garden bed on the other side of a yarn-bombed tree, is a house-shaped cupboard named the Annie Borat Street Library. When I opened one of the doors I found this biography on the inside (along with one for William Barak):

Annie-Borat (c. 1834-6 – c. 1870-1). The daughter of Bebejan and Tooterie, Annie Borate (a.k.a. Borat or Boorrort or Barat), the youngest sister of William Barak, was born on the Plenty River at the beginning of Victoria’s European settlement. She bore several children, with her eldest son, Robert Wandin (Wandoon) surviving to adulthood. Annie and Barak’s brother Parrpun negotiated a ‘sister exchange’ in which Annie was married to Andrew Pondy-yaweet of the Kurnai Brataualung tribe of Gippsland in exchange for Lizzie, Barak’s first wife. This was a marked departure for our people as it was usual practice to marry within the Kulin confederacy. The formation of new alliances signalled the extreme threat European settlement posed to our collective survival. All present day Wurundjeri are related to Annie Borat (emphasis in original).

It was impossible not to notice how the urban landscape had changed in the intervening two years: construction partially obstructing the path I trod, several new apartment complexes altering the way sound travelled in the streets below, and blockades preventing access to spaces once available to the public. One section of my soundwalk is now impassable. The place where I read Brophy’s poem –at the base of a footbridge over the Upfield train line, accessed by a stretch of rough gravel next to the police bus depot – is barricaded and designated ‘private property’. Though it’s possible the barrier was installed in the interests of public safety, to prevent accidents by the train line, the sign made me think about how public space is carved up by commercial interests – how common space is redesignated, and becomes ‘owned’. Another new (and newly defaced) barricade, on Saxon Street outside Blak Dot Gallery, had thematically connected but historically distinct connotations.