On Art as Love (and everything in between)

Jessie Cole on writing

Was my father a good artist? Did his work have value? These were never questions that arose.

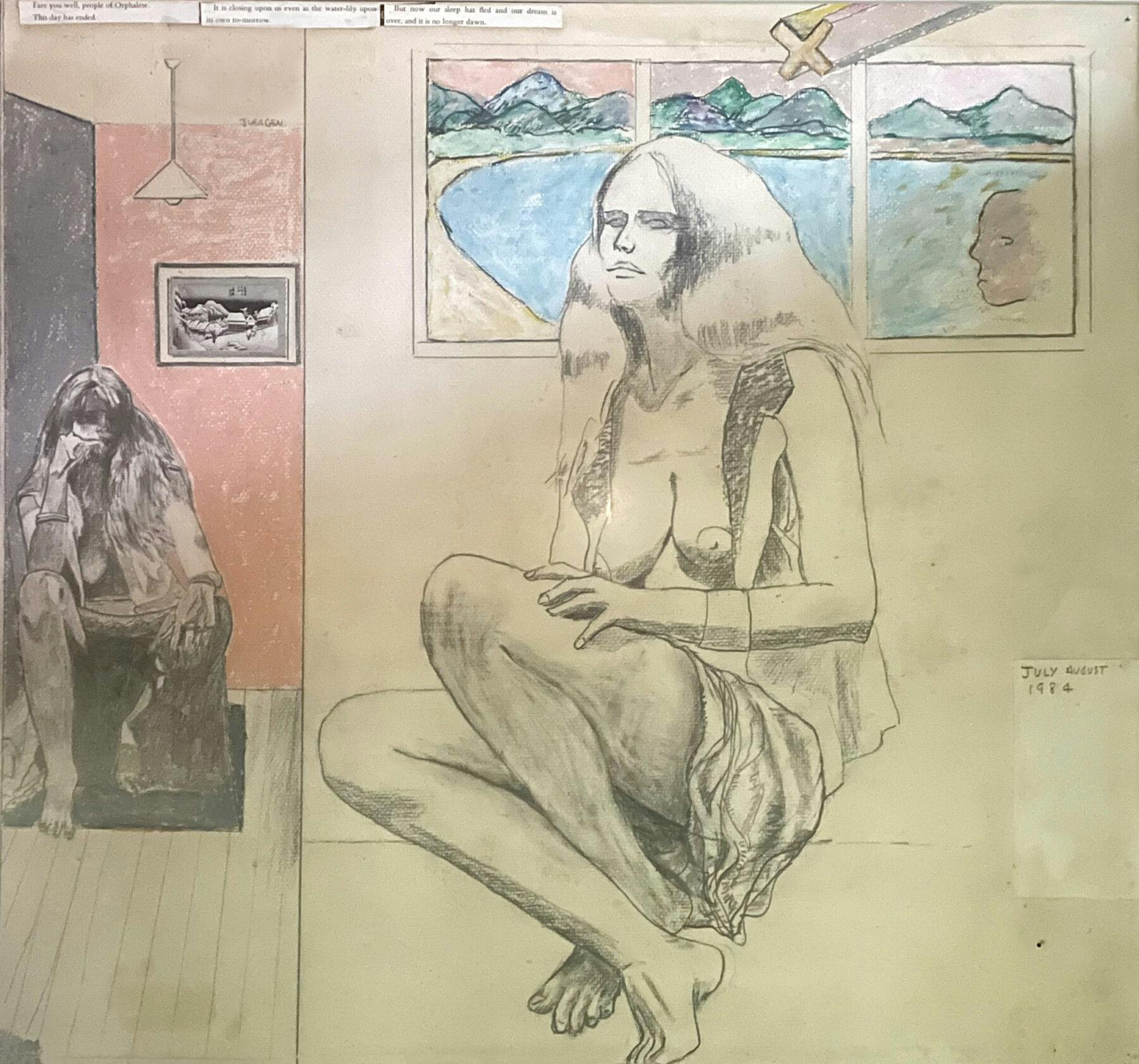

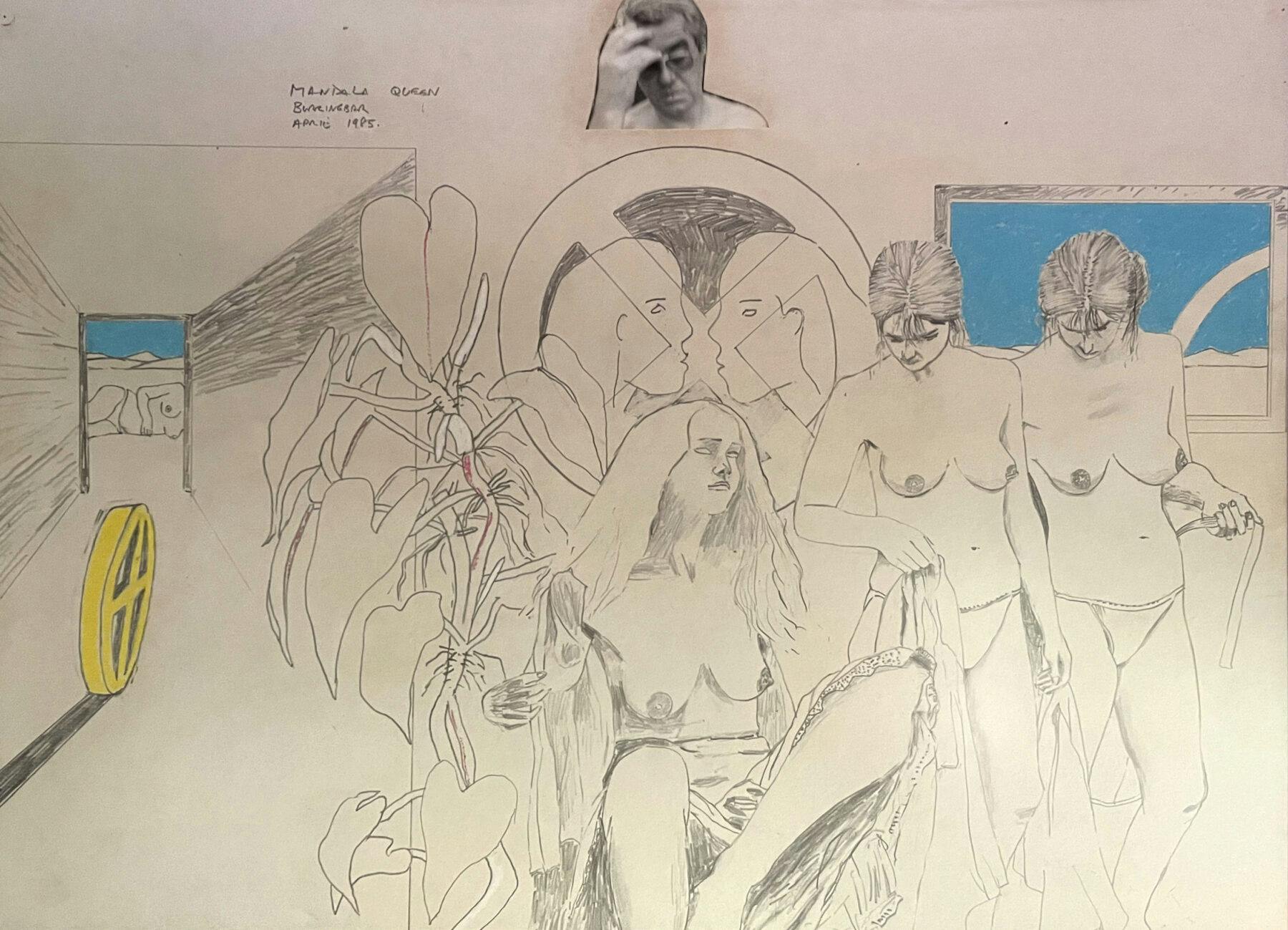

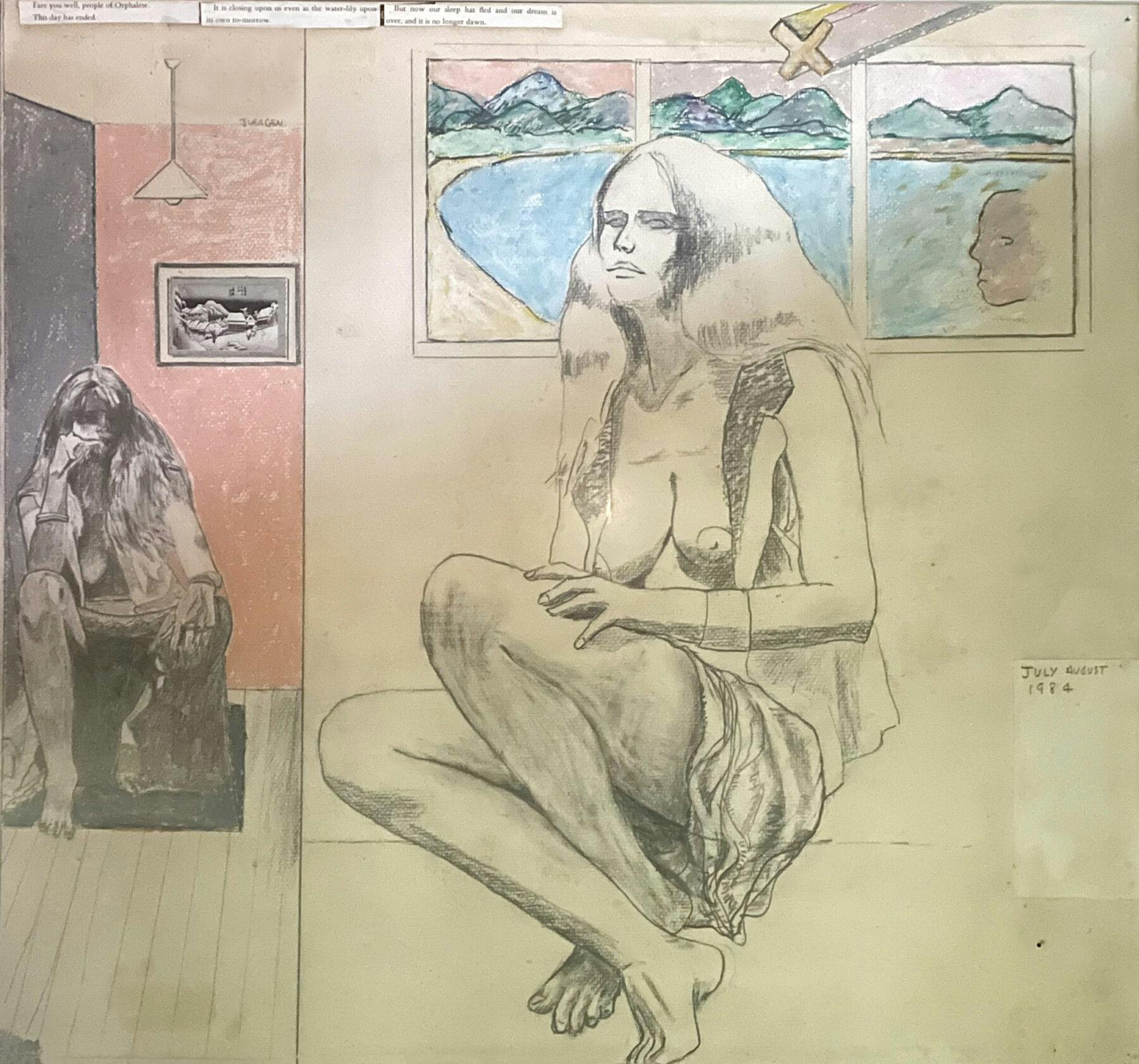

When I was a child, my father’s artworks covered all available wall space of our home. He worked mostly with lead pencil, with splashes of oil pastel colour and portions of handwritten text. Many of the drawings involved my mother, naked or half-naked, but as kids we were used to her naked form. Yes — it was the 1970s, and yes — we lived in a hippie enclave. As children, we barely noticed the artworks. Certainly, it did not occur to me that other kids might not have naked drawings of their mother peering down at them from every wall.

My father did not create these drawings often. Like me, he was a sporadic artist, producing, at most, two drawings a year. They were full scale projects, taking weeks, maybe months to complete. Careful, precise, thoughtful, often dark in tone, deeply personal. Was my father a good artist? Did his work have value? These were never questions that arose. Art in my household was an expression of who you were and what you were going through. As kids, we were encouraged to build skills in order to be capable of this expression, but the expression itself was always central.

My brother and I drew regularly. Our specialty was birds. I’m not sure what we were saying about ourselves, but birds were manageable. Smallish, colourful. My brother had natural talent — everything he drew looked lifelike, only better. I drew like a child. When my father got home from work, he would inspect our drawings carefully, my mother hovering nearby to intercede if his critique was too harsh. She wanted him to offer encouragement, he wanted us to build our skills. He was equally critical of both of us, even though my brother’s birds were superior. In time, I sensed my drawing skills would never be up to the task and I lost interest, but this central life calling — finding a medium for the expression of self, building skills to create it — remained.

In his youth my father won a university art prize even though he was studying psychiatry, pipping the art students at the post. I’m sure the win gave him a moment of gratification, though he never mentioned it to me. After my memoir Stayingwas released — about the suicide of my sister and father in my adolescence — old friends from my father’s university days got in touch to tell me what they’d known of him. This was when I heard about the prize. Each mentioned my father’s art, some of them sent me printed copies of drawings they still had in their possession, fifty or so years later. People who had not seen him since university, people who had not known that he was dead. I wondered about this young man who had made such a lasting impression. I tried to look at his drawings, adorning the walls of the childhood home I still lived in, with new eyes.

View from front door. Photo: Jessie Cole.

Mostly, my father drew his portraits from photographs, but sometimes my mother would sit for him. My brother and I were always there, playing in the background, this act of creation just a part of the swirl of life. There are two scenes I remember vividly. One, my mother crouching on the deck, naked from the waist up except for a vest, which was buttonless, and fell open to reveal her breasts. I remember being struck by the pose, which looked particularly difficult to hold, struck by my mother’s willingness to stay still in the pose for so long. But what I remember most strongly is the undercurrent passing between them. The eye contact, the eroticism. I was a child and did not have language for this kind of exchange, but that doesn’t mean I didn’t feel its potency. It hung there between them: a charge. The second scene was even more startling. My father asked my mother to lie naked in the garden, her back arched over a large pillow, hands and feet both resting on the ground, her body in the perfect shape of a rainbow. This was a vulnerable pose, it caught my attention. My father drew my mother as if the pillow was invisible, her body arched there in space. And once he’d drawn her, he sketched a beam of light coming from her vagina, as though she was the creator of all life. What was happening between them? I am acquainted now with the history of men creating art from their lovers’ bodies — of muses and the extractive, abusive quality of this exchange — but that is not what I saw as a child. My father was not creating art to sell or increase his social standing. He was creating art to hang on our walls. My father’s art seemed a reflection of his love, his interest, his desire. I believed the artwork itself captured the essence of both of them. And again, that strange charge between them in the moment of creation. In this jumble of unspoken lessons, I imbibed the sense that art-creation was a shared project. A collaboration. Artist and muse were involved in a dance, both bringing themselves to the end result: the work.

‘Mandala Queen’ Portrait of the author’s mother by the author’s father. Photo: Jessie Cole.

When I was fifteen, I was taught by an English teacher who was fierce, no-nonsense. Her teaching style was mesmerising but the occasional hard truths she threw our way were as bracing as slaps to the face. I had, from time to time, come across a lone classmate in the hallway quietly crying after receiving her feedback. For an English assignment we were asked to submit a piece of ‘creative writing’. I knew this meant a story that was made up, but that wasn’t what I wrote. It was supposed to be four handwritten pages, but I turned in ten. I titled it ‘My Sister’. There was plenty of material. When my eighteen-year-old half-sister, Zoe, took her life three years before, she’d left behind a diary of fragmented thoughts that I could not keep away from. When I first read it, at twelve, I’d understood that I was not implicated in my sister’s decision to kill herself, as the diary contained almost no mention of my existence. At twelve I was relieved, but as time went on, I tussled with how someone who had been so monumentally important in my life could have thought so little about me. My absence from Zoe’s diary pained me, but her one throwaway observation about me cut to the quick — ‘Jessie will never mature until she experiences rejection.’ Our entire relationship was encapsulated in that one sentence, as though my sister’s primary goal in regard to me had been to balance out my rejection-free-life. I wrote about this in my ten pages, and about how her suicide was such a final, irrevocable rejection, and I handed them in. I was apprehensive about going so far over the word limit, but the story had seemed to write itself. A few days later I could see my teacher was marking our stories in class. She had assigned us some kind of self-directed learning and she was multitasking. I knew when she got to my story, because she had to flip so many pages. She called me up to her desk at the front of the room. I expected a harsh word about my gross word limit violation. Around me my classmates chattered quietly.

‘Is this true?’ she asked me.

‘Yes.’ I had never been a good liar.

Her eyes narrowed. I knew I had failed the point of the assignment. I had not made anything up.

‘It’s very good,’ she said.

She picked up her red pen. A nineteen-out-of-twenty. This was unheard of for this teacher. Sixteen-out-of-twenty was a very high mark. I was stunned, my eyes welled. I had written a story, it felt like my first, about my dead half-sister, and it was very good. It had not occurred to me that this could be so. That my writing could be an expression of who I was and what I was living and also very good. Two things happened in that moment: I knew my teacher had seen me, that my heartache had become visible to her, and, after all those years of drawing birds, of never being able to communicate my inner world with any kind of grace, I had found a medium.

I did not write another story for many years. This awareness of my aptitude for capturing life in writing lay dormant. The prevalence of visual art creation in my community was so overpowering, writing-as-art was easy to forget. In high school, the artistic exchange that I had witnessed at home continued unabated. All my girlfriends — those shiny shiny girls — drew and painted and photographed and crafted. We all took turns being artists and muses. The exchange between bodies was so fluid, so dynamic, that the electric charge of creation seemed to be all around us. For birthdays friends would present me with portraits of me, or drawings of the things I loved: leaves, flowers, stones. Me, still terrible at drawing, would grind stones from the creek into paint and decorate their naked bodies, then photograph them, sticking the pictures on my bedroom walls. I once let a friend photograph all the places on my body with rolls of flesh, so she could practice drawing curves. Where were the boys in all this artistic endeavour? I don’t know. I barely remember them. My high school boyfriend never drew me a picture, but he made me a lot of gourmet toast. A few years later, at university, two friends used photographs of my pregnant body as their end-of-year major works. For my baby shower my girlfriends gathered and everyone drew my semi-naked form and gave me their pictures. I have no memory of this being planned, it felt impromptu. But someone had to have thought of paper and someone had to have pencils. When my babies were born, I received drawings of them as gifts which I stuck on the front of their photo albums. Recently, I turned 45 and two friends gave me small artworks they had created of my forest homeplace. I wrote about them, they made pictures for me. Even now, we shift from artist to muse and back again.

My mother never drew. She never wrote. But she made our clothes, mostly without patterns — freehand — and we tried them on throughout the process so she could get the right fit. She reupholstered our couches, she cooked elaborate meals, she planted our forest and tended it. All these were acts of creation. Like my father’s artworks, they were not made for profit or to increase public standing. When a visitor came, they might comment on my father’s latest drawing, or inspect it, but they were just as likely to comment on my mother’s new couch cover or my new dress. I now know that my family was arranged around the gender norms of the day, but I never assumed that my father was the sole or more important creator. I believed families and friendships involved collaborative creation, and creation was an act, or expression, of love.

Detail of drawing by the author’s father, of the author’s mother. Photo: Jessie Cole.

My father never tried to sell his art. He said the pictures were too important to him — he could not part with them. He did get each one expensively framed, and spent time working out where on our walls they might fit. Once framed, a picture — for him — was finished. When is writing finished? In my late twenties I wrote the first draft of what would — fifteen years or so later — become a published book: Staying. I got several copies of this first draft printed and bound at the local print shop and distributed it among my remaining family. I did not feel that it was finished. For me, publication felt like framing. Except I was sending a book out into the world, not hanging a master copy on my wall. With books there is no master copy, there are only prints.

‘Publishing a book is such a horror,’ a writer friend messaged me on the eve of the publication of my most recent memoir, Desire. ‘It’s only marginally less horrific than not publishing a book.’ I laughed out loud, though truer words were never spoken. But why this need for an audience? For this framing, this finish? I spent many years enveloped in silence. Post-suicides, marginalised by complicated grief. It is unsurprising that I might need to be heard. And perhaps my father was fudging when he claimed he could not bear to part with his pictures — perhaps it was the prospect of being critiqued by strangers he found hardest to bear.

The narrative of Desire follows the arc of my last relationship with a dogged intensity. ‘Cole seems to have performed the ultimate act of love in writing this book about the man. Clearly she loved him. And clearly, she has turned that love into a work of art,’ one reviewer wrote, a few weeks after the book was published. This assertion, coming at the end of the review, startled me with its directness. In truth, I had seen the writing as part of the relationship. On my visits to his city, this man had tended me, much like my mother — cooking, listening, crafting a welcoming home space — and I had created art from what we shared. I was anxious about how my lover would receive my work, but I’d assumed he would understand it to be a contribution, an offering. In the first year after our relationship folded, he expressed a wish to read the book before I sent it to my publisher. But when that time came, he decided he would not. My faith that this offering would be welcome might seem baffling, but, in the context of my life, not so much. Would my lover have read my writing if it was never to be published? If it remained just between us? I cannot know, and, in any case, by that stage there was no ‘us.’ But perhaps writing — banging those keys in a private room — can never involve the collaborate exchange that was present in the art-creation I had grown up around? In writing, there is no eye contact, no shared charge. Perhaps, all along, I had been labouring under a misapprehension. Is this a mea culpa? Since finishing the book, living through the breakdown of the relationship it charts, I have been grappling with why writing a memoir like Desire would seem so natural to me. Was it an act of love? Or was it something else entirely?

My father also drew pictures of me. Sometimes these artworks were collaborative. He would give over a space on the paper to my child-fingers and I would imprint it with my being. My sections of the artwork are usually noted in his handwritten text, so as an adult I can see where I have made a contribution. These pictures are like time capsules. My father’s portraits of my brother and I are the first thing a visitor sees when they walk in my front door. Me, aged five. My brother, aged three. Both of us look soulful, worried even. It’s hard not to see in them an intimation of what was to come.

Not long ago, one of my father’s artworks, propped on top of a high cupboard, fell off. The glass smashed and the picture itself was newly revealed. I looked at it properly for the first time in years. In the bottom lefthand corner was a sketch of my father’s favourite armchair with a coffee table and a bottle of wine. The midrange of the drawing was a mess of loose pencil sketching, almost scribble, with some oil pastel colour in yellow and pink and peach and green. In this section was a small photograph of me, captioned in my father’s handwriting. Were some of the scribbles mine? This was not noted. In the top lefthand corner was a torn piece of paper, glued on, which was printed with the words: Knut Hanson/ MYSTERIES. Perhaps it was once the title page of that book? Beneath the photograph of me was a self-portrait of my father, in profile, with a deep gash along his face. The caption below the self-portrait was blurred and unreadable. My father had written something and rubbed it out with an eraser. Along the top was written: NOVEMBER 1980/ Photograph of Jessica 3/ Mysteries 1892. And in the bottom righthand corner it said: DEDICATED TO MY BEAUTIFUL GIRL JESSICA. What was I to make of it?

In the first real story I wrote, about Zoe, my dead half-sister, and how little she had thought about me, I was tussling with the unevenness of love. How someone so significant in my life could have seen me as so inconsequential. I did not know, in writing Desire, that I was writing the same story. But stories are built, constructed. A writer decides the scope, the parameters. We zoom in on our preoccupations. Stories can never contain everything.

A baby’s first language is sensate: how safely they are held, the lovingness of the touch. I knew love in that first language. My parents held me gently against their warm animal bodies. I knew care, I knew trust. There are photos of my sister carrying me as a baby, confident, smiling, me settled on her hip. Photos of me snuggled on her lap as a toddler, wrapped in her easy embrace. Photos of her standing behind me the year before her death — hand in my hair, gazing down, her face awash with tenderness. Some things are beyond words, but the body knows. After sex, I would lie along the length of my lover’s body, listening to his heartbeat, his hands resting gently on my back. I knew love in my first language, the language of touch.

If your loved one is dead to you (or you to them), or (gulp) actually dead, what can you do with this love? Turn your heartache into words, paint a picture, sing a song. A devastating final act — a suicide, a breakup — does not erase all that came before. Your love existed. Declare it! You exist. They existed. I wander my home, the house of my childhood, looking at my dead father’s artworks still hanging on our walls — all his monumental, difficult love. Maybe, maybe, it is enough?