comes from attempting to reconcile cultural protocols of knowledge sharing with the enormous capacity for technology to consume, learn, proliferate beyond our intentions. There is some convergence too with the mechanisms of cultural protocols and the technical protocols computers use to exchange data.

This All Come Back Now: Overture

Mykaela Saunders on First Nations speculative fiction

This essay is extracted from This All Come Back Now: An Anthology of First Nations Speculative Fiction, edited by Mykaela Saunders and published by UQP.

There were only a few ways to find new music when I was a teenager, growing up in a small town in a pre-internet world. I found old music easily enough, flipping through the old girl’s records and listening to them with headphones plugged in to the speakers in the lounge room, studying the cover art and liner notes and lyrics as I sang along. But finding new music was a different, more difficult quest. There were not yet any music blogs to scour or YouTube rabbit holes to get lost in. Radio sucked, even the few alternative stations that we picked up in Tweed. I was too poor to just go out and buy albums whenever I wanted, and CDs were pretty hard to flog, so if I wanted an album I had to be sure I loved it, to justify spending my meagre, illegal wages I earnt cooking brekky at the local markets.

And so mixtapes and compilation CDs were my gateways to finding new music that excited and moved me.

I loved receiving the gift of a mixtape made by someone whose taste I relied on to open up my world. I could count how many of these people I absolutely trusted on one hand: mostly older, cooler mates, and my older brother. I loved making my own mixtapes too: the craft of taping songs off other songs, nailing the precise timing of starting and pausing, and carefully transcribing the song list – sometimes whiting-out an old tape sleeve that had already been whited-out and written on dozens of times over.

I found real joy and pride in making a mixtape that was coveted by people I respected. I loved the ritual of swapping mixtapes with others, always hoping to hell that you all recorded the song names and artists accurately, and wrote them down in the correct order of their position on the playlist, lest you begin telling people how much you love the wrong band. There was no greater shame than in being a poser.

Later on, I discovered small punk and metal labels that would put out compilation CDs seasonally, to showcase forthcoming samples from their bands. There were music magazines that did this too. And when I belatedly got the internet, I found blogs dedicated to making playlists of seminal bands in whatever genre you could think of. Thank god for all of these pedlars and purveyors of new music; listening to their offerings felt like being at some mythical overseas music festival where you could check out hundreds of bands and find new favourites from the comfort of home. These compilations were hit and miss, but sometimes it felt like a powerful and prescient god had tapped into your mind and curated this gift especially to your tastes.

Short story anthologies are like mixtapes, and I want you to think of this book as a burnt CD from me to you, a way for you to sample new worlds, a mishmash of styles gathered together that speak to similar themes, and an opportunity to find exciting writers you might not have otherwise come across.

In 2004, Nalo Hopkinson and Uppinder Mehan edited the anthology So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial science fiction and fantasy. In 2012, Anishinaabe scholar Grace L Dillon edited Walking the Clouds: An anthology of Indigenous science fiction. I read both North American anthologies in 2016 and they excited me so much they set me off on my current path of researching and writing my own speculative fiction (spec fic), in both creative and critical work.

Closer to home, over the last few years we’ve seen a rising tide of ‘un-Australian futurism’ anthologies, and the more the merrier, I reckon – this is the way that nascent movements grow strong and interesting, and that new ideas and approaches begin to unfurl.

After Australia (Affirm Press) was published in 2020 after editor Michael Mohammed Ahmad commissioned work that responded to the provocation: What might Australia look like fifty years from now? Contributors answered in a variety of genres. Also in 2020, Collisions: Fictions of the future, a Liminal anthology (Pantera Press) was edited by Leah Jing McIntosh, Cher Tan, Adalya Nash Hussein and Hassan Abul. The short stories came from the longlist of the 2019 Liminal Fiction Prize, and while not all stories are spec fic, they all write into the prize’s theme of ‘the future’. Contributors from these anthologies are, respectively, ‘diverse writers’ and ‘people of colour’;1 After Australia features four First Nations contributors while Collisions features two. Both anthologies speak back to white Australia’s literal and literary territorialism over the past, present and future with a multiplicity of fresh voices.

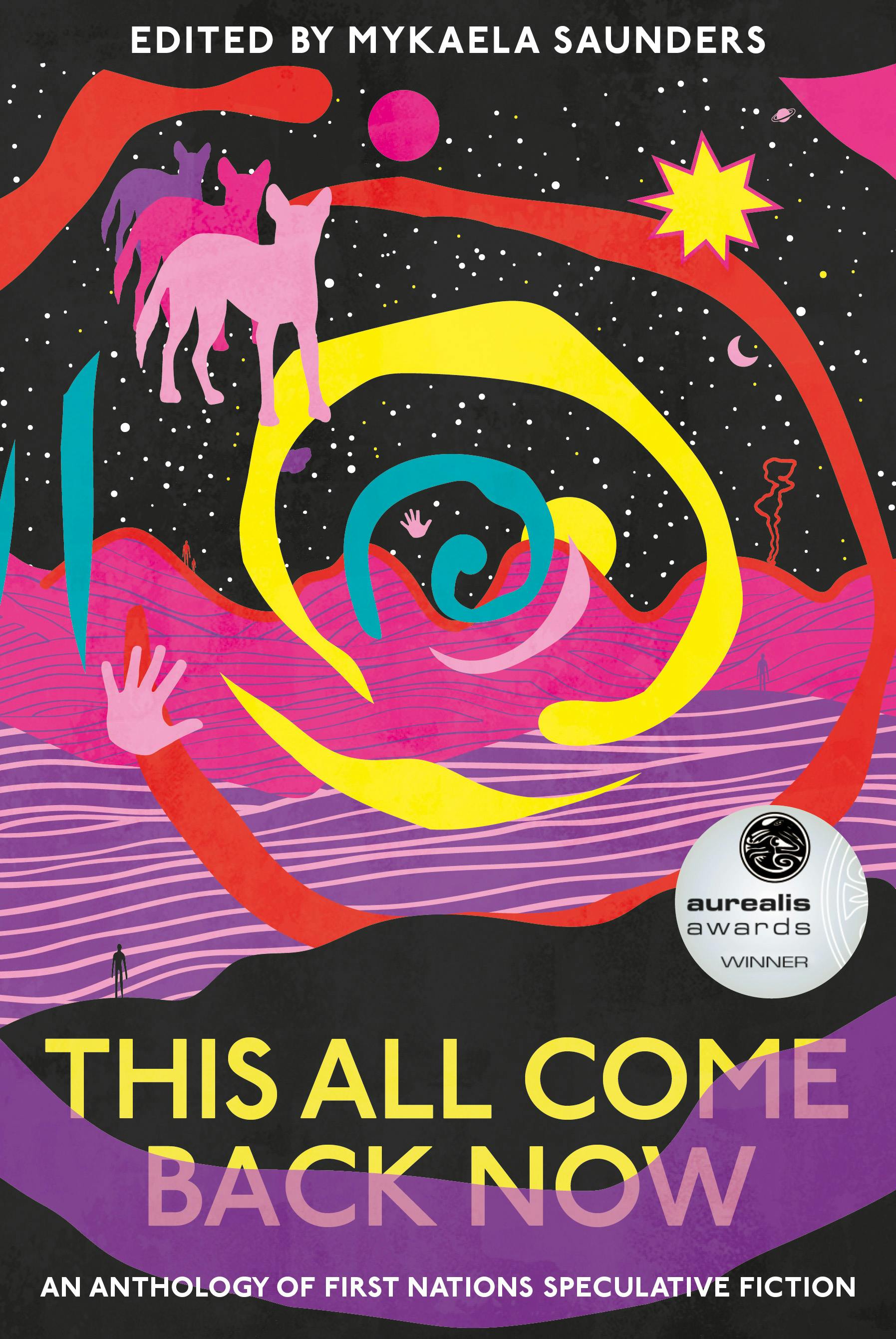

But until now we had yet to see an anthology of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander speculative fiction, written and edited entirely by us. And with the jaw-dropping cover art created by Jessica Johnson at Nungala Creative, and the book itself designed by the talented Jenna Lee, this has been a one-hundred-percent First Nations project (well, besides owning the means of production).

But why, in 2021, is this a world first?

Over the years that I’ve been studying Indigenous spec fic, I’ve had countless conversations with people interested in my work. One question I’m always asked is, ‘Why isn’t there much Indigenous spec fic being written?’

‘But there is!’ I answer. We blackfellas love reading spec fic and writing our own, so a better question to ask is, ‘Why isn’t there much Indigenous spec fic getting published?’

Well, it is. It’s just not being published in the places you’d expect.

Anecdotally, many First Nations spec fic writers I’ve spoken to have had their work embraced by mainstream literary publishers after being rejected by Australian spec fic publishers. Indeed, of all the stories in this anthology that have been previously published, none of them come from traditional Australian spec fic publications. They were all first published in mainstream literary publications, and a few of them have won lucrative literary prizes.

To be fair, there aren’t many spec fic publishers in Australia, but those that do exist have historically not published much of our writing. Some might say this is a matter of taste – as though taste is objective, and just a matter of style or aesthetics – but taste is judgement, which determines the ways we read, enjoy, and interpret stories, and this is always, always shaped by our world views, which are always cultural.

Of the many spec fic stories about First Nations characters and cultures, the vast majority have been written by non-Indigenous writers, and published through traditional Australian spec fic channels. It’s gotten a little better recently, mostly, but there’s a long way to go, considering that for most of its history the Australian spec fic publishing industry has been hostile to our stories and indeed our presence, while mining our cultures and pillaging our spirituality to trade in tired themes and tropes.

Australian and global spec fic prizes have, too, been historically averse to actual First Nations writers but welcoming of non-Indigenous writers who win awards for biting our style and flogging our experiences for their storylines. This is still true at the time of writing. No wonder we feel hostile to the Australian spec fic community too.

I don’t say any of this lightly or pithily, or to provoke a controversy for the sake of the discourse. I’m saying this with my whole chest, hand on heart. I say this with the authority of somebody who has sought out and read every single Australian spec fic story that features at least one Aboriginal character. And I say this loud and clear: the vast majority of this characterisation is no good, whether they’re infantilising or fetishising or assimilating or demonising us, or some combination of these.

I’ll concede that some non-Indigenous writing about us has gotten a little better, but not always, and in any case, a few half-decently rendered characters over the last decade can’t possibly make up for a solid century of grotesque representation.

Traditionally, Australian spec fic publishers have preferred fake, palatable versions of our stories over the real deal, but this is no surprise as it mirrors the same proclivities of mainstream literature, which of course is just a microcosm of this country at large. They want the nice stuff: the ochre, the opals, the stoicism, the spiritual purity, the creatures, the cosmology, the mystical shamans and evil sorcerers, the magical properties in our blood, the portals in our scared sites. But nobody wants to reckon with the effects of state-sanctioned violence, of ecocidal policy, of genocide, of eugenics.

If this all sounds harsh, consider being an Aboriginal spec fic fan: the rare times you see your people written into the genre it is mostly by non-Indigenous authors, most of who use us and our stories as plot devices or to play out their own colonial Dreamtime fantasies.

Spec fic is a big and porous basket that holds all the slippery types of stories together, including science fiction, climate fiction, alternate history, futurism, post/apocalyptic fiction, utopian and dystopian fiction, fantasy, horror, gothic fiction, surrealism, magic realism, and slipstream fiction.

Spec fic, as a Western genre, employs devices that our cultural stories have dealt in for millennia – the difference is, to us these stories aren’t always parsed out into fiction or fantasy, as they are often just ways we experience life. For example: time travel isn’t such a big deal when you belong to a culture that experiences all-times simultaneously, not in a progressive straight line like Western cultures do. And talk to any Aboriginal kids, from any community anywhere on this continent, about gussies or ghosts, and you will find a captive audience of experts, and maybe a highly skilled storyteller if you’re lucky.

There are so many common spec fic themes that are just stone-cold reality for us. Right now, right across this continent, we are post-apocalyptic and not yet post-colonial, so all those violent histories of invasion and colonisation must be read as apocalyptic by any standard. Related, Mad Max is probably the best-known Australian cli-fi story, but for our people, who have seen unfathomable ecocide enacted hand in glove with our own attempted genocide, all stories that take place in unceded lands post-1788 are climate fictions. Finally, and perhaps more universally, some say that spec fic deals in the ‘not real’, but what of the absolute fantasy of continuous consumption on a finite planet?

So it sticks in my craw a little to call this a spec fic anthology, given that for many non-Indigenous people that means it’s all completely made-up. But I do concede that these are spec fic stories while I underline that these are not stories that diverge from reality, as defined in a Western scientific materialist sense. These stories are about our realities. Lisa Fuller explains this much better than I can in her 2020 essay ‘Why Culturally Aware Reviews Matter’ in Kill Your Darlings. ‘Myth This!’, her story from this collection, alludes to this too.

Spec fic is just one toolkit of many that we use to tell our stories, and if I have to hierarchise labels, the stories in this book are First Nations stories before they are spec fic stories; that is, they centre and celebrate our communities, cultures, and countries while using spec fic tropes and techniques as literary devices. We make these tools our own rather than using them in the way Australian spec fic writers use them. We use them in cultural ways, respectfully, and we don’t allow the tools to use us, as we refuse to pilfer our collective cultural consciousness for shock tactics and plot twists.

In This All Come Back Now, it is clear that the writers aren’t overly concerned with prescriptive spec fic protocols, as their stories only sometimes affirm accepted genre conventions, sometimes extending or subverting them, or else collapsing them into new forms, or discarding their conventions entirely.

Some of these writers have been writing spec fic for years, and some have won awards for their work. But for Evelyn Araluen, Timmah Ball, Loki Liddle, John Morrissey, Merryana Salem, Jack Latimore, Krystal Hurst, and Kathryn Gledhill-Tucker their story in this book is their first foray into spec fic, a departure from what they’re best known for, respectively: poetry, essays, music, short fiction, critique, journalism, visual arts, and tech writing. This is more proof that discrete categories of genre, form and mode don’t restrict our people in our storytelling wholeness.

I’d been thinking about editing this anthology for a few years, purely because I wanted this anthology to exist. I waited patiently for someone else to do it, but it didn’t happen – but that’s okay, because I eventually felt arrogant enough to do it myself. I am indebted to Dillon, Hopkinson and Mehan for showing me ways that it can be done, and for inspiring me to do it too.

The parameters of this project have always been fairly plastic as I believe that the shape of an anthology like this should be determined by the stories, rather than forcing choices to fit into a preconceived paradigm. However, in the call for submissions, I laid my cards out on the table.

I sought work written by us, with a strong preference for stories written for us and about us. After reading so much of our literature, I’m much more interested in stories that centre and celebrate First Nations characters, that focus on relationships inside and across country, community, and culture. I did not want this to be an anthology full of pan-Indigenous, written-to-teach-white-Australia-a-lesson-about-itself stories that could be mistaken for coming from other cultures.

I encouraged all blackfellas to submit, whether emerging or established writers, unpublished or widely so, whether they had written spec fic before or were writing it for the very first time. I emailed dozens of writers whose writing I loved with an invitation to submit, and I’m happy to say that many are in this book.

I wanted to collect the best of our spec fic writing together in this basket of like-minded genres, so that the stories could all be read in their proper cultural context, side by side with their siblings. And so I opened up submissions to already-published works, as so much of our strong and interesting black spec fic has been published in journals and other anthologies; it would have been a tragedy to exclude the stories by Evelyn Araluen, Karen Wyld, Jasmin McGaughey, Samuel Wagan Watson, Loki Liddle, Krystal Hurst and Hannah Donnelly. For the same reason, it was important to include extracts from seminal, longer texts by Ellen van Neerven, Sam Watson Snr, Archie Weller and Alexis Wright, and standalone stories from books by Alison Whittaker and Adam Thompson.

On that note, I can’t tell you how special it is to feature stories by a father and his son in this anthology. Sam Watson Snr passed away in 2019, and with the blessing of his family I’ve included an extract from The Kadaitcha Sung, the first Aboriginal speculative fiction novel, published in 1990. I landed on this particular extract through yarning with Watson’s son Samuel Wagan Watson, whose story I am so proud to include in this book alongside his father’s. How did we decide on this excerpt? Well, this part of the story is set in my community, in Fingal, a place beloved of both Watsons and myself, so that was that.

I had the pleasure of reading over sixty pieces in a few short weeks, and as I read and made my decisions, purely based on my own tastes, the collection began to shape itself organically, like a clump of crystals growing from a common source and forming around each other. And what did we end up with? A multi-gender, multi-generational, multi-perspectival community of exciting thinkers and writers, coalesced around our collective storytelling campfire.

In choosing, I always leant more toward the experimental, outlandish, surreal and satirical, rather than the traditional, predictable, conventional and solemn. Some writers sent in two stories, and I often chose the most cultural of the two. There were around forty stories that I couldn’t include, so keep your eyes peeled for an explosion of First Nations spec fic in the coming years (if literary publishers continue to publish our spec fic, and if traditional spec fic publishers begin to open their gates up a little).

In my experience, all the best projects are built on good relationality, as this is what builds healthy communities. In the call for submissions I guaranteed the cultural safety of contributors through my editorial guidance, and I strongly suspect that’s why such a flood of stories came in. I stipulated that all writers would have creative control over their stories, that I wouldn’t try to make their voices sound white, and I’d protect their work from other unnecessary meddling.

A hands-off approach is attractive for some editors, perhaps seeming simpler when editing across cultures, and not wanting to step on toes. But not for me. Rather than discarding every less-developed story outright, I committed to nurturing work that showed potential through a collaborative editorial process. This was sometimes an intensive exercise but it was always rewarding once the story came out gleaming.

I only decided on the book’s title after I had spent time with the stories; I think choosing a title before you know what stuff the book is made of is a little like naming a baby before they are born. I had a one-page shortlist of titles; these were phrases taken from the stories themselves that jumped out at me during editing. And when I saw a draft of Nungala’s cover art, I decided. (On that note, if you happened to pick this book up based on the cover – good! You clearly have great taste.)

This All Come Back Now is a line taken from the opening story, ‘Muyum, a Transgression’ by Evelyn Araluen. Throughout this story of departures and returns, the spectral narrator speaks of herself coming back like falling star or like scintillation or like nothing. All manner of other things come back, too: waves will be coming back for their rivers, and dead creatures come back, bringing comfort. At the end of the story, as the narrator crosses a threshold she’s resisted since the beginning, she announces ‘this all come back now’, alluding to the singularity of thought and feeling that she’s now become, at one with everything, right at the end of consciousness.

In this anthology, ‘this all come back’ for us, too – all those things that have been taken from us, that we collectively mourn the loss of, or attempt to recover and revive, as well as all the things that we thought we’d gotten rid of, that are always returning to haunt and hound us. Characters return, sometimes in different forms, and things are returned to characters. There are themes that come back through this book, time and again – f amily and other kin, Old People and ancestors, government interference, corporate greed, the destruction of land and water, the archive, technology, language, law, ghosts, hauntings, warm and deep belonging and despairing alienation. This All Come Back Now speaks to what Grace L Dillon calls ‘Biskaabiiyang – Returning to Ourselves’ in Walking the Clouds. It also speaks to our cultural conception of time as everywhen, or all-times at once.

These are stories that take place outside the bounds of consensus reality, showcasing a variety of possible worlds, and they are all rooted in our ways of being, knowing, doing2 – or becoming. Some of these writers are summoning ancestral spirits from the past, while some are feeling around in the muck of daily living for their stories. Others are looking straight down the barrel of potential futures, which always end up curving back around to hold us from behind. Not many of these stories are utopian, though our cheek and humour shines through in even the grimmest and heaviest of stories.

A good playlist will take the listener on a journey; the relationships between contiguous songs make sense and transitions are seamless, and in this way short, disparate songs are strung together to create a unique larger, longer composition.

‘Open with a banger and close with a burner’: this advice is sometimes promoted by editors of literary anthologies and curators of musical compilations alike. I didn’t follow this adage, but I didn’t not follow it either. Instead, I sequenced these stories in such a way that, together, they tell a bigger story; each of the stories is in conversation with its neighbours, bound to each other by through-lines of genre, character, setting, theme or trope.

The anthology opens with Evelyn Araluen’s moving and mythic ‘Muyum, a Transgression’, which won the Nakata Brophy Prize. Set in between worlds, this haunting story is narrated by a young ghost in Araluen’s unique and powerful prose. This is Aboriginal gothic, where the sadness is born from intimate knowledge of place and people and what has been done to both, not horror arising from the land itself as mysterious entity, as with regular gothic.

We then move into the magic realism of Karen Wyld’s Borderlands Prize-winning story ‘Clatter Tongue’, which takes place in a contemporary urban street, school and home. Young Treanna’s sadness and anxiety invokes the purging of colonial refuse, and the way Wyld renders metaphor and symbol into story is astonishing and lovely.

‘Closing Time’ is Samuel Wagan Watson’s urban ghost story, an atmospheric exploration of the father–son relationship, and the ways that the past seeps into the present. Set in autumn 2020, it channels and exudes the global ambient anxiety from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Watson’s distinctive lyricism is, as always, evocative.

Kalem Murray also explores the father–son dynamic in the fun and creepy bush horror story ‘In His Father’s Footsteps’. This story is based in Murray’s home country, and the texture of his world is finely rendered. It’s a beautiful invocation of the bush and the mangroves, and the delights of crabbing seen through the eyes of a moody teen.

In Lisa Fuller’s ‘Myth This!’, a Murri family goes camping on a cold winter weekend. This is another bush horror story that speaks to some of the same themes as Murray’s – but with a slight shift in tone. This, too, is really a story about family, and Fuller’s characters are vibrant and relatable.

Another urban ghost story, ‘Jacaranda Street’, is Jasmin McGaughey’s take on the ‘be careful what you wish for’ trope, made fresh by a young family finding the mundane in the magical, and vice versa, and kept grounded by arguing over money. Through deadpan phrasing in unusual situations, McGaughey’s wry and dry humour is a delight.

‘The Kadaitcha Sung’, the titular excerpt from Sam Watson Snr’s novel, is the first of four stories that feature the pub as a setting. The story begins with the young Kadaitcha Tommy Gubba going to the pub to drink with his mates then sneaking off to make love. He then attends to his sacred duties in other realms and realities, before arriving back to the Fingal mish to be told off by his fierce Aunty. This excerpt is representative of the tones and textures within the novel: light and heavy, mundane and magic, loving and violent, and ancestral and futuristic.

‘Snake of Light’ is set in a country pub, a place often associated with small minds and big violence – and Loki Liddle plays with audience expectations of where the danger comes from. This unearthly urban fantasy speaks to both our ancient spiritual ways and to contemporary small-town problems, while also being a satisfying tale of revenge.

Adam Thompson’s ‘Your Own Aborigine’ may seem like an absurdist take on the near future, but it is not so unlikely given that the government has before repealed section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act in order to get away with targeting Aboriginal people in a similarly embarrassing and infantalising manner. This is good Aboriginal satire: written from but not for the white gaze. The possibilities of this story are both funny and frightening.

Is John Morrissey’s story ‘Five Minutes’ about a repressed public servant masquerading as a sci-fi writer, or the other way around? Either way, through Morrissey’s clever layering of different realities, as his protagonist projects his struggles onto the page, those struggles begin to bleed back into his life. It’s funny, very meta, vicious, a bit cooked, and is a withering look at the public service, and at the Australian literary landscape too.

Now we begin to move into further-off futures, into worlds that are currently unrecognisable – but may not be too far-fetched give or take a few things.

The next sci-fi story is Merryana Salem’s ‘When From’, a satirical corporate dystopia from an Aboriginal perspective. Salem has extrapolated on the current pandemic and Hollywood’s proclivity for filming in Australia, and added some time travel and mixed in a strong dose of Aboriginal cynicism for good measure.

Set in a future urban Redfern, ‘The Centre’ by Alison Whittaker is a disturbing thought experiment, grounded in cultural and historical fact, that grapples with a truly blackfella future in ways that poke fun at the present. Particularly prescient is Whittaker’s climate-changed future, and her reckoning of abolition within a gamified reality, which is reminiscent of all the quick-fix sloganistic government programs that are constantly dreamt up to solve our problems.

In Timmah Ball’s ficto-critical ‘An Invitation’, a jaded ex-urban planner gets an offer via email that triggers a meditation on the lead-up to the architectural apocalypse. Ball takes a hard look at corporate personalities and the white queer power dynamics that enable them. Anyone working in the arts today will recognise this as a hard-won Aboriginal insider’s perspective, and so it might be worth paying attention to Ball’s messages.

Laniyuk’s ‘Nimeybirra’ is a trans-generational meta-story, told in the epistolary form. The story explores familial relationships through time, looking near and far into the future and coming back again. The cross-generational connections and call-backs throughout the story show the continuum of ancestors and descendants, connected through story, and offers a glimpse of what trans-Tasman First Nations solidarity could look like.

Ellen van Neerven’s ‘Water’ is set in a near-future Canaipa/Russell Island. The government are about to create a separate ‘Australia2’ where Aboriginal people will soon be segregated – at the expense of the islands’ ancestral inhabitants. An abridged version of the novella that originally appeared in Heat and Light, ‘Water’ focuses on the relationship between the human Kaden and the plantperson Larapinta, showing how their fascination with each other grows as its own story within the broader saga.

My story, ‘Terranora’, is set just south of ‘Water’, and in a similar saltwater mangrove world. ‘Terranora’ takes place in my own community, in the Tweed, and is my take on the classic ‘a stranger comes to town’ set-up. The story explores belonging and relationships inside a tight-knit Goori clan who’ve reasserted sovereignty in a dizzyingly climate-changed future.

Archie Weller’s sprawling futurist novel Land of The Golden Clouds, from 1998, is set on a hot, irradiated continent where people live in distinct cultural clans, and is a fantastic example of a hopeful yet post-apocalyptic future. This extract, ‘The Purple Plains’, focuses on the Aboriginal Keepers of the Trees, who Weller imagines living far into the future the way our ancestors did. This extract is full of creation stories from all over our continent, with a bit of romance and danger thrown in.

Set in a post-apocalyptic feudal wasteland, Jack Latimore’s ‘Old Uncle Sir’ is arranged on the skeleton of Hamlet. Always incredible and sometimes uncomfortable, the narrator’s lyrical voice is a fresh mix of gritty, gross and playful. He invokes a rich and violent world as he contemplates his place within his messed-up family, and wonders whether he might someday found his own trash kingdom.

‘Dust Cycle’ is an excerpt of the titular chapter from The Swan Book, Alexis Wright’s Australian Literature Society Gold Medal-winning novel. This story is a shining example of surreal futurist fiction, especially as it speaks to dystopian policies and the absurdity of government in the here and now, and projected visions for the country and climate in the future. This excerpt sets up the climate-changed world, with Aboriginal people living in an army-controlled compound. We are introduced to the protagonist Oblivia and her beautiful swans, as well as Aunty Bella Donna of the Champions, and the Harbour Master, a healer for the country.

Krystal Hurst’s haunting and beautiful story follows a small family of climate refugees across a burnt and desolate country as they seek the fabled Lake Mindi, where they believe rebirth and renewal will be waiting for them. Hurst’s story collapses multiple genres together and offers us a fresh and cultural take on the apocalypse, particularly in the ways that the characters comfort each other in crisis.

The collection ends with two considerations of a post-human future. Hannah Donnelly’s micro-fiction ‘After the End of Their World’ encapsulates a whole world in less than five hundred words. Sometime in the past, disappearing humans created the sisters of the Skylands, non-human custodians of country. When the sisters visit earth to conduct a cultural burn, they are forced to feel grief for the first time – and they learn of its transformative power.

The anthology closes with the beautiful, lyrical ‘Protocols of Transference’ by Kathryn Gledhill-Tucker. The way the narrator yarns to the AI with such affection, sadness and gravity in this post-human future is truly moving. This story, in the author’s words:

It is with joy and pride that I present the world’s first anthology of blackfella speculative fiction – a love-letter to kin and country, to memory and future-thinking. I hope you enjoy this mixtape of weird, black and excellent stories from some of our most brilliant writers.

Bugalwan!

Mykaela Saunders

Yarrgehmbu, 2021