To the end that sloath and villany should be detected and the just and diligent rewarded, I have thought meet to create an account of time by a Monitor …

– from the Law Book of the Crowley Iron Works, c. 1700.

Our work is made possible through the support of the following organisations:

Matthew Allen and Jennifer Mae Hamilton on academic work

How long does academic work take? How long should it take? Even more troubling, who gets to decide what is valuable and necessary work for an academic today?

To the end that sloath and villany should be detected and the just and diligent rewarded, I have thought meet to create an account of time by a Monitor …

– from the Law Book of the Crowley Iron Works, c. 1700.

We are collaborating on an essay about time measurement and the value of academic work. We first had the idea at a union meeting in which we were wrestling with our university’s academic workload policy. Then we considered it further over a drink. We discussed it extensively over WhatsApp and agreed to pitch an essay to a journal. We then both, independently, worked on some initial thoughts, read some papers, researched ideas, wrote up notes, and read each other’s. We had a formal meeting on campus over coffee where we made a plan for the research, draft structure and writing. Meantime, one of us took a detour to read a new Australian campus novel; while the other researched the history of work measurement. On the back of all this preliminary work – on and off the official clock – we wrote the first draft in several chunks of two to three hours either together or over Zoom. We each prepared sections of the draft, read them over and edited them into a final version which we sent to the editor of this journal. Our editor already had a backlog of work to get through, and meantime her partner got COVID. Weeks passed. But when we received her feedback we worked through it together and separately to confirm this final version.

This process took considerable time, but how much time is difficult to say.

We began working on this piece about three months ago (a remarkably short turnaround for academic publishing), but during this period, we also answered emails, attended meetings, taught classes, and worked on other research projects.

For example, Matt was in his teaching-heavy trimester. He taught three units with a total of over 200 students, for which he reviewed and updated unit materials (lectures, lecture notes and resources), set the assessment tasks, prepared and delivered classes, coordinated and conducted marking, consulted with students over email and the unit website, managed extension requests, and performed other administrative work (contracting casual markers, timetabling, recording and uploading results, attending markers’ meetings etc.). The reading and thinking involved in this teaching will feed into his ongoing research.

Jen was in a research-only trimester, working on a few writing projects and a podcast, co-building a community network, supervising a cohort of postgraduate students, acquitting grants, attending meetings, reading new scholarly books and articles, re-reading old ones, writing op-eds for local publications, attending meetings, and signing student forms. Next term, they flip roles, Matt is research- only, and Jen takes on a big teaching load. This rhythm of teaching and research and the fruitful balance between them is critical for our work and to our vision of the academy: we believe that we’re better researchers because of teaching, and better teachers because of research.

All of this teaching and research is work and it all takes time. Measuring any or all of it is fraught with difficulties and presents a series of questions, at the core of our essay:

How long does academic work take? How long should it take? Even more troubling, who gets to decide what is valuable and necessary work for an academic today?

These questions are asked increasingly often within Australian universities but academics are less and less involved in answering them. In practice our work is usually measured by so-called ‘academic workload models’, which are either developed through intensely politicised negotiations or simply imposed by university management. Even under such models, individual workloads are often agreed between academics and their supervisors, sometimes in ways that are non-transparent, inequitable, capricious, and unfair. The story we tell below about the struggle to measure and value academic work illustrates not merely the plight of our university or the university sector in general, but also the broader challenges of creative and intellectual labour under surveillance capitalism and its obsession with innovation and metrics.

We are both mid-career scholars, straddling 40, and senior lecturers in balanced positions – our work notionally involves an evenly weighted combination of teaching (40 per cent) and research (40 per cent), and a component of service to the organisation (20 per cent) – at the University of New England in Armidale (UNE). We both came to the profession in the mid-2010s after the collapse of the academic job market in Australia and as a result, our relatively secure academic careers and our balanced roles are an exception to the norm for scholars of our generation, many of whom are insecurely employed on exploitative casual contracts. That we have ongoing academic jobs is not because we are smarter or better than our peers, but rather that we were lucky. In this, we resemble other members of a shrinking middle class, clinging to the rungs of the ladder of opportunity as secure professional jobs become increasingly rare, and property ownership ever less attainable. This position – relatively secure amidst increasing precarity – gives us insight into the importance of working conditions where academics are valued, trusted and allowed to take time to do careful work. We need to redefine and then carefully maintain this privilege in order to share it.

To be clear, this is not nostalgia for an earlier version of the career. Graduating into a precarious, managerialist university of intensifying workloads, we are different from the generation above us – the professoriate and the emerita – who can, and often do, recall a lost ‘golden age’ in the academy, where there was more jobs, more public funding, more respect for universities and academics, and, accordingly, more time for our work. As Hannah Forsyth has argued in her history of Australian universities, this ‘golden age (if there was one)’ was a brief episode, the product of larger structural changes to post-war society, and the benefits were largely confined to a white-male-dominated elite. We do not need to return to this time. While one of us (Matt) is a fourth generation academic, the other (Jen) is first in family to attend university; but both of us can see that the democratisation of universities and the decline of the God-professor are healthy changes. In all likelihood, we would not be colleagues without them. Equally, though, we aspire to devise and establish working conditions that allow contemporary academics the time to do their work well, and to train the next generation of academics to replace us. In other words, we both reject elitism and insist on the intrinsic value of academic work.

Unfortunately, the same historical processes that have made universities more accessible and less elitist, have also made them larger, more expensive and harder to manage; and this has contributed to the current crisis of academic overwork. Forsyth notes that currently about 40 per cent of the population will study at a university during their lifetimes, a hundred-fold increase from the end of the Second World War. As Australia shifted to a mass system of higher education the funding of universities has become increasingly politicised, especially since the Whitlam government made study free (albeit for what was then a small minority of the population). Throughout the past half-century, critics have called for universities and the academics who work at them to modernise their methods, become more productive, efficient, market-driven and entrepreneurial. The Dawkins reforms of the late 1980s accelerated both trends, increasing student numbers and introducing new systems to ‘rationalise’ the sector, notably the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS) which shares the cost of university study between the student and the state, and the Australian Research Council which distributes research funding on merit. As Forsyth shows, these pressures and the systems they spawned, have led to an ‘audit economy’ where academics are measured on crude metrics (articles published, citations, student numbers etc.) and these metrics are often gamed by universities as they compete for shrinking government support. The recent reduction in funding of 14 per cent per student in real terms, pushed through by then Education Minister Dan Tehan in 2020, and accompanying rhetoric about ‘job-ready’ graduates and ‘industry-linked’ research are thus the culmination of longer-term trends.

As universities grew, they became more complex, and this led to the growth of the university executive and middle management. As Croucher and Woelert show, since the 1980s reforms, academics have made up less than half of university employees (now averaging slightly more than 40 per cent), while the proportion of staff in senior and middle management roles has doubled. As government subsidies shrink per student, these business-oriented managers have responded by increasingly directing their budgets towards hiring more managers and consultants, investments in capital works (seen to attract overseas students) and hiring casual teaching assistants rather than ongoing and balanced academic staff. As faculty retire permanent jobs have not been replaced and casual or sessional staff cover the gap such that almost 70 percent of Australian university staff are on either casual or fixed-term contracts.

These changes have contributed to the simultaneous intensification and devaluation of academic work. Teaching and research are what makes a university a university. So, unsurprisingly, with more managers and fewer securely employed academics and professional support workers, the demands on employees doing the core work have increased. As anyone who has been subject to an efficiency drive will know, the effort to do more with less either reduces quality or leads to overwork. Increasing student numbers and raising demands for research outputs, combined with decreasing appetite for investment in teaching and research, have led to stress and burnout. In addition, the managerialist devaluation and decentring of academic work in the institution – through both structural divestment and increasing precarity of academic professionals – is arguably one of the causes of the wider social devaluation of expert knowledges. Is it a coincidence that we have to make the public case for the trust value of scholarly knowledge (about climate change, vaccination, and the economic importance of frontline care workers, for example) when the institutions that generate the knowledge do not themselves trust and value the people doing this vital work? It is in the face of this crisis that we insist that academic work is a worthy public and private investment, valuable to society in immeasurable ways. But in order for academics to do their work well we need time, and the freedom to direct our time.

The value of academic work rests upon the expertise of the academics who perform it; and expertise takes time. In our own disciplines of history and literature, reading is especially important since our focus is on texts and sources that are almost exclusively literary. But all academic work needs time for careful and close reading since writing is the main mode of research dissemination and scholarly teachers must remain up to date in their fields. For the most part, such reading does not need dressing up with fancy terms or technologies. It is basic, fundamental work and what it needs is time. For example, reading a single academic book chapter or article can take 30 minutes to two hours depending on how difficult the content, how fast you read and how many notes you take. More broadly, taking one’s time to form a careful, rigorous, considered position is at the core of expertise. Synthesising all this into a lecture or seminar, or snazzy online teaching material, takes time. Hasty research and teaching preparation undermines its own claim to authority.

Such considered, slow, time-consuming expertise also depends upon academic freedom, including the freedom for academics to determine their research and teaching agendas. In contrast to the tedious claims of right-wing culture-warriors, academic freedom is not individual but collective. As Thomas Haskell has argued, it is fundamentally grounded in the authority of a community of experts – a discipline or, more commonly today, a transdisciplinary or hybrid collective. We are not claiming an unfettered right to express controversial opinions (at least no more than anyone else) but rather a shared freedom from extra-academic influence, including corrupting financial pressure. As Haskell says, academic freedom is based on ‘professional autonomy and collegial self-governance’ grounded in rigorous criticism and review within the community of experts. Only fellow experts are qualified to assess the value of academic work, and by extension, how long it takes.

While this claim might seem self-serving and even elitist, the principle of academic freedom has much larger social implications. Judith Butler argues that in democracies, public funding should necessarily exceed the control of the state:

The state funds that which it cannot fully control – that is how democracies should work – and that freedom from censorship and control is a central meaning of academic freedom. Academic freedom preserves the incalculable dimension of thought, the future of thought that eludes prediction and control … freedom from censorship and control is a central meaning of academic freedom.

For the state or industry, and by proxy, university management, to control academic work or determine in advance how long it should take limits academic freedom and threatens democracy itself. If academics cannot take the time to do their work, as set by the norms of a scholarly community broadly construed, then the value of academic expertise is undermined and the public investment in universities compromised. Expertise takes time and is worth paying for.

But increasingly, universities are intensifying academic workloads, undermining expertise and impinging on academics’ time for rest and recreation. Since we joined the profession, academics have been expected – assumed – to work outside their formal 37.5 hour working weeks. In their 2016 book The Slow Professor, Berg and Seeber illustrate this point by analysing the time management tips provided to academics by their employers and consultants such as not working more than 10 hours a day, getting up early to work on research projects, and thinking carefully about ‘which work you save for the weekends’. This culture of systemic overwork reflects the fact that, due to the way managers have devalued academics in the growing university system, there is too much core academic work for the continuing academic staff. No matter which way you slice it, building more infrastructure and paying corporate consultants millions of dollars to redo the sums will not change that, especially if universities seek to grow student numbers and continue to do world-class research. Those of us who are doing the core work in the traditional academic roles are co-opted into exploiting the growing insecure workforce we now rely on, while we exhaust ourselves trying to produce the research on which our careers depend. Driven to compete in what Forsyth describes as an ‘esteem economy’, academics are sacrificing their time to their careers, contributing to a crisis of mental health within academia, and especially among the insecurely employed.

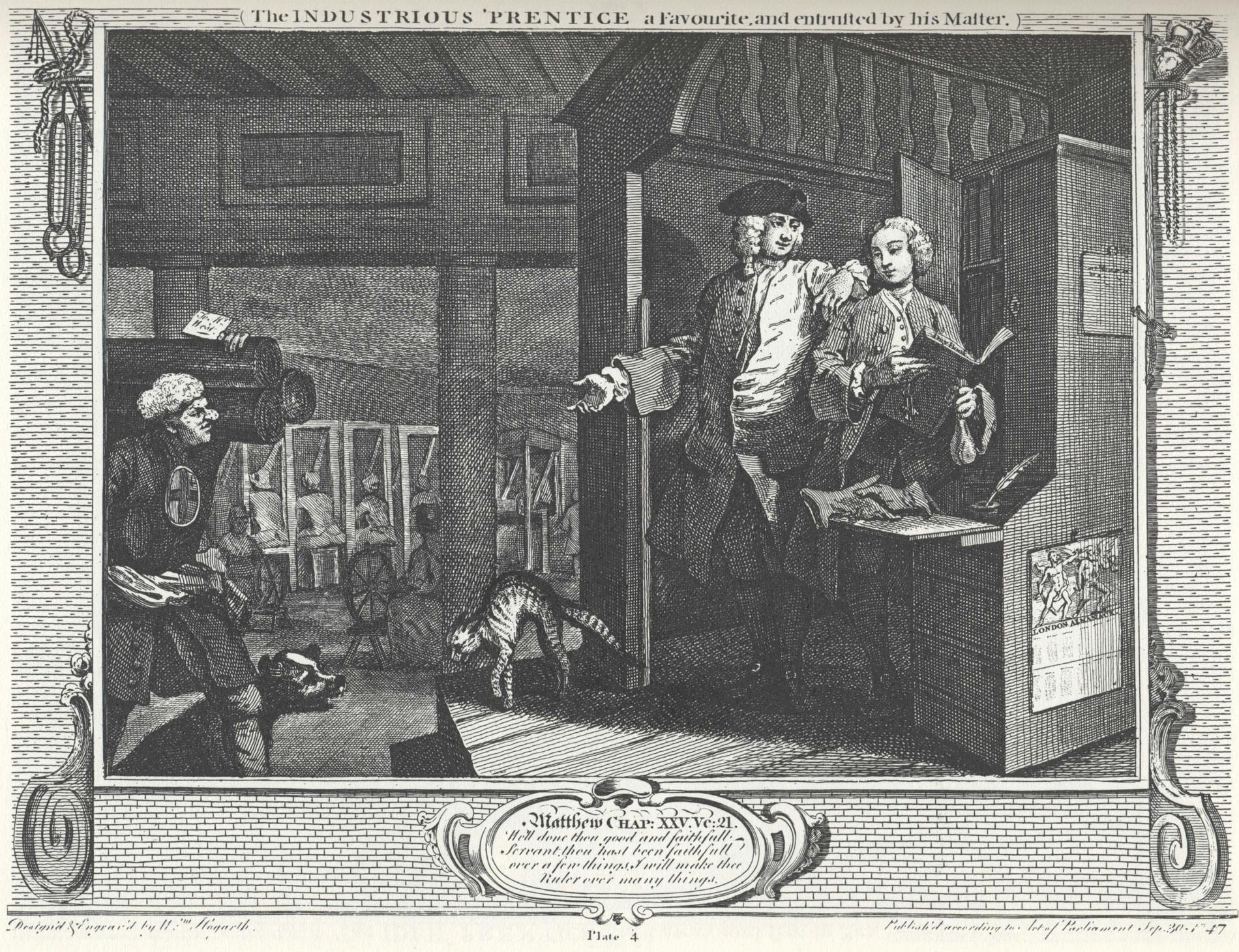

As the epigraph to our essay illustrates, the desire to control workers in relation to clock time – to punish ‘idleness’ and reward ‘industry’, is nothing new. In a famous essay on ‘Time, Work-Discipline and Industrial Capitalism’, E. P. Thompson explores the shift from the ‘natural’ work rhythms of pre-industrial societies, shaped by the seasons, the tides and the hours of daylight, to modern capitalist industry, shaped by the clock. It is a history of how new technology helped time become money.

Since the industrial revolution, efforts to account for and manage workers’ time have only increased. Ideas of ‘scientific management’, pioneered by Frederick Taylor and famously employed by Henry Ford in his factory production line, sought to improve productivity by systematically measuring workers time and outputs, an approach that is fundamental to modern theories of management, including those increasingly imposed on universities. But, as Thompson also shows, the discipline of the clock was radicalising for industrial workers who learned to use time as money in their struggle for rights, fighting for and winning time limits on their work. Notably the eight-hour movement and its promise of ‘eight hours labour, eight hours rest, eight hours recreation’ – which underlies our notional 37.5 hour week – was first won by Melbourne stonemasons in 1856, as a result of effective industrial action.

But technology has blurred the distinction between work and recreation, and has once again facilitated more intense monitoring and management of workers’ time. Smart phones, laptops and ubiquitous internet have encouraged the practice of working from home, which was accelerated by the response to COVID. While digital technologies create greater flexibility for employees, they also make it easier for employers to subject their employees to surveillance, to quantify their performance, and to employ them on a limited basis in a ‘gig economy’. In this context flexibility becomes a manager’s euphemism for precarity. In addition, software that links metrics and social media (like Google Scholar and Academia.edu) make it easier for workers to measure themselves against often unreasonable standards, a problem which is particularly acute within the esteem economy of academia. As Michel Foucault famously argued, modern social control is frequently internalised with the ideal that we monitor and discipline ourselves. The pressure academics so often put on themselves to work outside of work hours is a classic illustration of his argument, but the same pressures and responses are found across all creative industries. Reflecting on this, Amelia Wallin suggests that ‘if the eight-hour workday indeed is a monument for workers, then it is a monument in ruins’ and calls for ‘new systems of remuneration and imagination … to reclaim our time, our care’.

Advocating for work-life balance for an academic in the 2020s requires both engaging with the changing nature of our work in relation to contemporary technological changes, while also re-asserting the aforementioned principles of research and teaching taking time and needing freedom. In studying the logics of time management and productivity in the knowledge economy, Melissa Gregg makes the claim that there is a ‘general inability of labor activists to articulate an effective chronopolitics’ for contemporary workplaces. This, for Gregg, is largely to do with the inability to fully apprehend how time-use changes with technology. What would a ‘chronopolitics’ for the contemporary Australian university look like?

The story of the struggle to measure academic teaching workload at UNE provides one answer to this question. When we commenced our jobs at UNE, academic workload was largely measured in terms of student numbers. Staff had to teach an agreed number of students and if they exceeded that number they received workload relief, usually in the form of casual support. But UNE was an outlier and a laggard. In general, most Australian universities measure academic work in terms of hours, under workload models imposed by management on their staff, which accordingly reflect how long they would like academic work to take. Managers decide the time they are willing to grant for particular tasks and staff are required to work to the standards imposed on them. In a clear example of how this can lead to exploitation, academics at one Australian university were given 2.5 hours for the preparation and delivery of a new one-hour lecture; that is, ninety minutes to write the lecture from scratch, and sixty to deliver it. Faced with such a model academics can choose to lower their standards of teaching and research, or to exploit themselves. They can work to the model and harm their students by reducing the quality of their teaching to what is possible in the time prescribed. Alternately they can take longer than the model states and either sacrifice their research time, harming their own careers, or sacrifice their free time, harming their families, social life, mental health and wellbeing.

During the last round of enterprise bargaining, commencing in 2017, UNE management were determined to move away from measuring workload in terms of student numbers and shift to measuring our time. In 2020 they finally secured a new Enterprise Agreement which mandated an hours-based workload model. However, perhaps due to the protracted 30-month bargaining process, and the historic strength of the local union, the workload clauses in the new agreement contained significant protections. First the workload model was to be created by an eleven-person Academic Workload Committee (the AWC) with two management representatives and nine academics (three nominated by the Union, three elected and three chosen by the Vice-Chancellor). Second, the model had to be ‘evidence-based and accurately reflect the time taken to complete the work’.

The members of the AWC debated this principle extensively and determined that it required the hours for tasks within the model to reflect the actual time taken by academics at UNE. They commissioned a (very) detailed survey of what they believed to be a comprehensive list of work tasks and asked staff how long they took. Despite the level of detail, the survey had a remarkably high response rate: 47 per cent of academics completed the sections on teaching preparation and delivery and 20 per cent completed all relevant sections. By averaging these individual estimates, the AWC arrived at average times for UNE academics as a whole and their recommended model used these survey averages as the basis for its hours.

It is here that the work of the AWC differs from most past practice in Australian universities. In contrast to the tradition of management prescribing how long tasks should take in a hypothetical future, the model developed and recommended by the AWC is based on evidence of how long work does take. For example, the AWC found that the time required for preparation of a one-hour lecture varied widely depending on the degree the content changed, and recommended a range between two hours for updating an existing lecture and ten hours for writing a new lecture from scratch. Thus, rather than disciplining an ideal future, the proposed workload model measures an actual past: the evidence of how long our work takes informs how much time we receive to do the work. Importantly, such a workload model would prevent management from simply ordering academics to take less time. If they wish to make our work more efficient, they must first demonstrate that proposed changes to work practices actually reduce how long work takes. It is, sadly, on such minutiae that we need to focus to begin to take back our universities – and our workplaces in general – from managerial control.

The story of the AWC is not over – indeed the status of our workloads is currently the subject of a fractious industrial dispute. Getting evidence-based and accurate workloads is itself hard work (the AWC has met more than 60 times and members estimate they have spent hundreds of hours each working on their model). If we get them, keeping them is likely to be even harder. We are under no illusions about the struggle to come.

But this is the real lesson of the recent history of the rise of the managerialist university. We have lost so much already. If academics don’t pay attention to their conditions of labour, commit to repeatedly arguing for the value of the work and actively fight to improve their conditions – which includes, but should not end at, struggling for fair and transparent workload modelling in managerial terms – then academic freedom, and the expertise it protects, will continue to decline. Research will be limited to what critical geographer Tom Slater terms ‘decision-based evidence making’, contracted by industry to woo investors. Teaching will be an exercise in marketing credentials to bored job-seekers for jobs that are on the verge of redundancy. Academic work will become the metrics used to measure it: a series of increasingly meaningless tasks and outputs. The logic of austerity will predominate with fewer and less secure academics completing more work. Productivity will be shown to increase; expertise will meaningfully decline.

It is here that the struggle to measure work accurately at UNE has a wider significance. The trends which are transforming academia from a meaningful rewarding career to a precarious ‘bullshit job’, and academic work from an intellectual calling to a game of numbers, are happening everywhere – and accelerating. We are both young(ish) professionals and everyone we know in our middle-class social circles – circles that, we imagine, resemble the readership of this journal – is experiencing the same crisis.

To be clear, fixing this problem, is itself hard work. We can neither rely on nostalgia for an imaginary past, nor can we hope current university management will do it for us. In the first instance, we must pay attention to what is happening in the present and repeatedly reassert the need to take our time. Time to do core academic work, time to read, time to write, time to discuss, time to teach, time to experiment, time to connect with students and colleagues, time to give feedback, time to hire new colleagues and build our fields, time to ask questions and be unsure of the answers, time to build quality relationships with collaborators, time to deliberate, time to browse the library, time to build trust in each other, time to not know what we are doing and not to know what impact it will have, time to do a failed experiment, time to write wish-lists of what a better workplace would look like.

Centrally, we must claim fair, transparent and democratic academic participation in both the determination of academic workloads and the direction of the academic work. Insisting on time for core business – research and research-led teaching – is a vital step towards a fulsome reimagining of the university itself. In the Australian context this means rebuilding faith in higher education institutions to produce scholars that we trust can do their jobs. It means not having these folks spend large chunks of their career defending the right for time to both teach and research, because doing both while training the next generation of scholars is what it means to be an academic. At the same time, it also means recognising and valuing how a university contributes to improving lives and worlds, beyond the development and sale of commodities and patentable ideas. It means seriously reckoning with the university as a colonial institution and fully investing in how it can be otherwise. It means demanding the government and university management reinvest in open inquiry and education, to create the conditions where students do not leave university saddled with debt. For graduates, this will also catalyse rethinking what it entails to study at university in order to participate in a society, in terms that far exceed ‘job-readiness’. Given all that has happened to the university in the last few decades, this is not a simple task. This is a long-term process and we’ve only just begun.