18 TRUCKS WITH 200 COPS

PASSED THIS WAY AT 12.00 MIDNIGHT 1.2.77

TAKING, SNEAKING, URANIUM

TO WHITE BAY

WHAT MORE CAN I SAY?

Our work is made possible through the support of the following organisations:

Tegan Bennett Daylight on literary generations

Introducing the Frank Moorhouse Reading Room project, author and critic Tegan Bennett Daylight reflects on the generational shifts that have shaped Australian writing as well as the creative and industrial legacies of Frank Moorhouse.

In late 2021, as he moved into assisted care, the Australian writer Frank Moorhouse donated his decades-long collection of anthologies of Australian writing to Western Sydney University’s Writing and Society Research Centre. He died not long after in June 2022. The Frank Moorhouse Reading Room was established as a tribute to his lifelong advocacy on behalf of Australian writers and writing: his work towards fair pay and copyright ownership for all Australian writers, and his commitment to diverse voices, progressive thinking, and social justice. In this essay stream, we invite writers to help us unpack this singular archive, spotlighting the intergenerational concerns and affiliations through which Australian literature is constantly being shaped and reshaped.

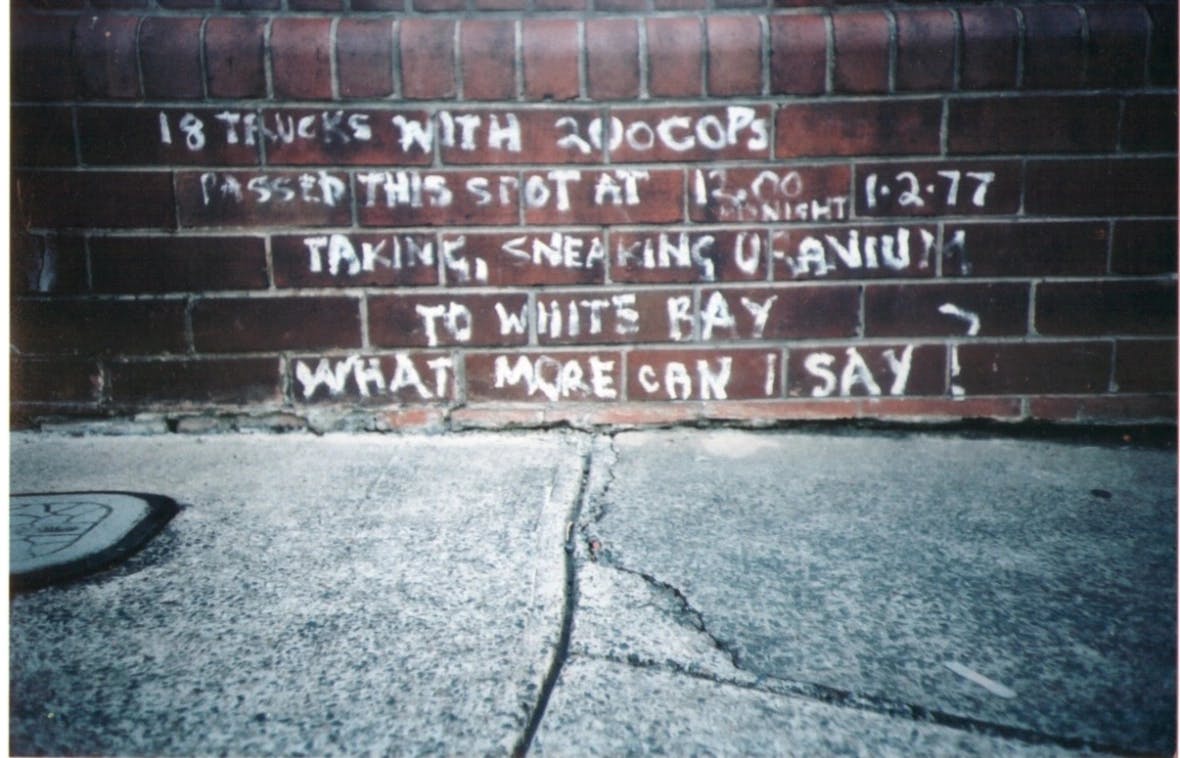

Image: Vanessa Berry.

I left home at seventeen, in 1986, for my first shared house in Young Street, Annandale. My rent was $75 a week, considered a little high at the time. In the 1980s housing was cheap and plentiful; my middle-class friends and I used to move house for fun. In this way I lived in Annandale, Newtown, Bondi, Surry Hills, Redfern, and Glebe before I was twenty-five. We found houses through real estate windows, word of mouth, and newspapers. Gay friends turned to The Star for listings that asked for ‘broadminded’ flatmates, necessary code for queer.

Every day as I proudly left my house in Young Street, on my way to uni or to work, I passed and reread the piece of graffiti that heads this essay.

18 TRUCKS WITH 200 COPS

PASSED THIS WAY AT 12.00 MIDNIGHT 1.2.77

TAKING, SNEAKING, URANIUM

TO WHITE BAY

WHAT MORE CAN I SAY?

I’ve never been able to forget this poem. It has a resonance that I couldn’t have named in 1986. I didn’t tell anyone I’d seen it; I just stored it away for something, some future project that I couldn’t even start to imagine. My oldest child now lives a block away from the site of the poem; the first thing I did after visiting their house was to check if the poem was still there. It isn’t. I miss it; I wanted Alice to see it, be near it, hear its echo. We’re all lucky that Vanessa Berry, as part of her brilliant project Mirror Sydney, took this photograph; kept a record.

It’s weird to get old. I keep hearing myself being terribly ironic about it with my younger friends and workmates, telling stories that reach back into an unintelligible past while rolling my eyes at how old I am. Encased in this irony is a dwindling kernel of conviction – that I’m actually not old, and that my young friends with their hasty, loving disclaimers are being honest when they say they don’t think I’m old either.

Obviously it depends where you stand. The only time I saw Frank Moorhouse in person I was ‘young’ and he was ‘old’ – meaning I was in my early thirties and he in his early sixties. He was reading aloud from his work, and I wasn’t listening because he was so old. And so irrelevant. I remember a suit, and a half-tucked shirt with a fair glimpse of belly. I remember damp, unkempt hair, and a special reading-literature-aloud voice. I remember seeing people my age in the audience looking polite and bemused, clearly wondering who this sweating person was, and why they had to listen to him. I remember thinking that he sounded like an ABC announcer from the 1970s. Which gives you some sense of how old I am. Eye-roll.

If Frank were alive, these words would not have reached the page – and so it is cowardly to write them now that he is dead. These words are rude, and they are ignorant. They are also partly true. On this page I am listening to myself talk, as Frank was that night in the bar, and on this page I am trying to tell the inelegant, disrespectful truth about him, about myself and eventually, about you. It’s part of the journey I’m taking towards embracing my own irrelevance.

I didn’t meet Frank for the last time in late 2021, when he was engaged in what I now know was a characteristic act of generosity. He was moving into assisted living and did not have space for his enormous library. I don’t know where all of Frank’s books went, but his anthologies of Australian writing, a piecemeal collection ranging from the late nineteenth century to the early 2010s, was given to my place of work, Western Sydney University. I was new to the university and had some workload to fill, and Ivor Indyk, publisher at Giramondo and friend of Frank’s, and Kate Fagan, Director of the Writing & Society Research Centre, gave carriage of the books to me. They were delivered not by Frank himself, but by his generous lifelong friends Carol and Nick Dettmann.

I had big dreams for those books. I imagined a Frank Moorhouse Reading Room, a place with the same feel as David Walsh’s private library at the Museum of Old and New Art: bustling yet peaceful, full of a quiet life. I thought perhaps our creative writing students could apply for short residencies – students who would benefit from the opportunity to closely study the Australian short story. I pictured these students drifting along the shelves, taking a book down, reading a little, staring thoughtfully into the distance.

Of course, Frank Moorhouse was not David Walsh, and Western Sydney University is not MONA. My dreams were not too big so much as too complicated. The anthology collection is not large, nor in good condition. It’s an extraordinarily valuable cultural artefact – whose value, I believe, will only increase – but preserving and extending it was not the sort of project that I could fund without the patronage of a creative maverick who was also a multi-millionaire. I’d forgotten that while there is money in universities, there is not enough for odd little projects like this one. This is how I found myself unpacking books in the office I share with Felicity Castagna on the Parramatta South Campus, shelving them as quickly as I could without regard for chronology or any other taxonomy, and sneezing.

Frank’s collection is incomplete and ramshackle, dusty and mouldy. Some books came apart as I took them out of their aged cardboard boxes, but not in a handle-this-illuminated-manuscript-with-special-gloves way. They were just shitty; bits fell off them, but they were there. Frank had thought it worthwhile to keep them, and over the following weeks, as I opened and shut book after book, I realised how lucky we were that he had done so. I was beginning to realise that much of the long work Frank was engaged in was – that ugly word again – relevant, and always would be.

You may have read Sam Twyford-Moore’s review in this journal of two recently published biographies of Frank Moorhouse. I’ve read the biographies twice in pursuit of this project. They are different books. I prefer the Lamb because of its intense and dazzling patience, although once Catherine Lumby’s lively account of her friend would have been my choice of the two. Lumby’s book is entertaining as well as informative, so I commend it to you. But as it turns out I’m more drawn to Lamb’s dogged cataloguing of Frank’s life. I want to know, in detail, how Frank became who he was. I want to see him preparing for the performance rather than having the curtain drawn and the lights on as I take my seat.

Who was Frank Moorhouse? Biographical detail: he was a white, uneasily cisgender man born in 1938 in Nowra on the south coast of New South Wales. He was much the youngest son of a loved and respected family, who were local business owners and committed Rotarians. His family had a history of suicide and mental illness, but Frank was the only one who seemed to manifest these possibilities – as well as other, more positive ones. It was imperative that he leave Nowra for the city. Once there he very quickly became a journalist, an editor, a writer, a teacher, and a lifelong activist in pursuit of open-ness, freedom, tolerance.

We might describe Frank as complex. In other words, he could be a terrible cunt. He was not, as I thought, a straight man with a quiet side hustle in dressing up. He was not a libertine, or indeed, a libertarian, despite his association with the Sydney Push and his insistence on sexual freedom. He was not straight. He was a heavy drinker. He never gave up fighting for Australian writers to be properly paid for their work. He was married once, to a woman, and did not behave well. He had a lifelong affair with a man. Finally, he never stopped writing, publishing linked short stories (which he described as ‘discontinuous narratives’), novels, memoir, and countless articles for countless journals.

You know a writer best through their words, and here are some of Frank’s – first from his semi-regular column in the Bulletin in which he addressed his cat, Ward, artfully using this ‘conversation’ as a place to air radical thoughts, like this one, published in 1973: ‘You see Ward, we need more words for the different sexes. I counted up – female heterosexual, male heterosexual, lesbian, male homosexual, bi-sexual, hetero-male transvestite, transvestites who prefer the same sex, multi sexuals …’.

From ‘The Gutless Society’, his 1963 article criticising the Push for its unacknowledged conservatism and exclusivity: ‘being privileged, as it can be argued we are, is anti-freedom. … The people who don’t like us to have much freedom, or don’t want social change, seem to win too many times. I think I know why: we are at the pub and aren’t showing any guts.’

And, from a letter to himself written in 1955, when he was sixteen (errors included here): ‘REMEMBER THAT KNOWLEDGE IS POWER; IT DEMANDS RESPECT; IT IS THE NECESSARY ASSETT OF A LEADER; AND IT IS THE ENEMY OF BIAS AND PREJUDICE – THE TWO SORES THAT HAVE FESTERED UPON THE BODY OF THE WORLD.’

I need to be the age I am to understand how radical these statements are; to understand how significant, how absolutely un-irrelevant Frank Moorhouse was and is to Australian literature and politics. I need to remember that Frank was my parents’ age and that although they espoused his beliefs and owned all of his books, they rarely spoke about them, or not in my hearing. Frank said things out loud.

Every time I came in to work, I continued my practice of shelf-drifting in front of Frank’s collection, taking books out and reading forewords, lists of contributors, acknowledgments. This is a writer’s version of consulting a family tree. There are so few Australian writers, and we are all connected. A contemporary acknowledgments page, which veers between the genres of Oscar speech and shopping list, is a kind of narrative whose real meaning can only be detected by other writers in the bat’s squeak of community and competition. Was I thanked? And if I was thanked, what was my position on the list of thankees? For a writer reading an acknowledgments page, an absence is as powerful as a presence.

And it was absences that kept calling for my attention when I consulted the collection. The family tree is full of gaps. I started an extremely casual process of counting. To wit: until 1930 all Australian anthologies contained only stories by white men. Around the 1950 some included stories by white women. Somewhere in the 1970s and 80s the anthologies began to include stories by ‘migrant’ writers (a sobriquet that reminds us that white Australians had always failed to think of themselves as ‘migrants’, much less invaders). After this there were one or two anthologies dedicated to feminism, almost exclusively written by white cisgender women. After that, collections about male queerness that occasionally included stories by queer women. Finally, collections that included stories by First Nations writers.

I didn’t know what I was going to do with the books; all I now knew was that I wanted to do something. Every time I opened the office the books looked at me from their disordered order, and I looked at them. I supposed that I was meant to write something celebrating Australian literature, or Frank, or the Age of the Short Story. But every time I thought about writing those essays, I felt very tired. To refine that thought, I felt tired of myself. I just couldn’t bear to hear myself talking about books again. It was with no little relief that I realised the time had come for me to be quiet (or at least quieter). And to this end I began the process of asking other writers to visit the collection with me, to drift along the shelves.

The Frank Moorhouse Reading Room came into being over a few nights in my office. The first writers to join me were George Haddad, Eda Gunaydin, James Jiang, and Ellen O’Brien. We drank a little wine, took books from the shelves and read passages and poems out loud to each other, laughing with horror and delight. I think all of us especially enjoyed an undergraduate love poem written by one of Australia’s most visible right-wing ideologues. It is so creepy. And so terrible. We look forward to sharing it with you.

This essay, then, is an introduction to both the past and the present. To the Frank Moorhouse Reading Room, whose curators are Eda Gunaydin, James Jiang, and myself. And also to Frank, whose strange, beautiful writing guides us as we go. Who I know would approve of the form this digital anthology is taking because he never stopped embracing the new, meeting it head-on, the way an artist should. I am hoping that this conversation with the books will continue, that more writers will visit the physical library and contribute to the virtual one. In my big dreams, these young writers will grow old themselves, and younger writers will take their place.

My own acknowledgments page: thanks to Felicity Castagna, Suzanne Gapps, Kate Fagan, Ivor Indyk, Melinda Jewell, and Catriona Menzies-Pike, whose engagement with the project was so important. To George Haddad, Ellen O’Brien, and Geordie Williamson, who joined us in conversation as the project took shape, and to my fellow editor/curators. Eda, James, George, and Ellen are in their 30s. Geordie and I are in our 50s. Our first contributor is queer writer Gina Ward, who is in her 70s, and has worked as a writer since the 1980s. I am so grateful to all of them, for their energy and their intergenerational wisdom, and want to thank them for getting this project in the air and flying.

A too-late thank you to Frank Moorhouse: for the generous gift of his books, but also for his bravery, his resistance, his broadmindedness. For the Public Lending Right, for copyright, for the Australian Society of Authors.

Now I think I know what the poem on the wall in Annandale means: it means that the radical conversation was always there. And that the radical conversation is happening now and will go on happening – in places you and I can’t imagine.