I’m going my fastest when a hand hits

my foot

I’m in

the medium lane and you're wearing

hand paddles

Come on

I’m trying to enjoy the show

Check out those blues

They’re stunning

Our work is made possible through the support of the following organisations:

Gareth Morgan on concrete pools and poetry

In this labile essay, Gareth Morgan plumbs the depths of the pool as a site of ritual, recreation, and the poet’s labour. From Mohenjo-daro to Carlton, Morgan recovers from the concrete history of public bathing a poetics of the locus amoenus.

I keep finding myself at the pool. I’m getting stronger. My brother touches my back at Christmas and says ‘oh’. I swim laps in anticipation of difficult conversations. I swim laps between pages of difficult poetry. I open up to the sun, and learn to ignore the rush of tiny bugs when I lie in the shade. The pool is zen, the pool is old and then renewed, brand new. I feel it.

This is at North Melbourne Pool, on the hill, but I’d really like to see them all – every last public pool in Melbourne. I’d like to get an Australia Council grant to go to the pool too. I wanna be the poet laureate of Melbourne – Australian! – public pools. How do you find yourself – as the year changes and the world is still full of unimaginable violence, children under rubble? A browning body trying to break even, get as close as possible to a good feeling, basic and comfy, and therefore out of the ordinary. A locus amoenus, the ‘pleasant place’ of pastoral poetry, where Virgil sends his singing shepherds. I’m looking for a locus amoenus in the liveable city …

‘The pool is leaking, its tiles are cracked, the amenities need upgrading, and $1 million needs to be spent on the filtration system’ (The Age). My frivolous desire to write about the locus amoenus is in dialogue with the hard slap of money, time, and neoliberal ideology … The one and only academic conference I went to last year featured a panel with three white academics, one of whom talked about water (deep oceans), which ended on a glibly sincere but jarring mantra: ‘I want a million dollars’.

I want a pleasant place.

I’m reading a book at the pool about the pool to know it better: These Are Different Waters by Ella Skilbeck-Porter (ESP). How does the poet find herself? ‘I found myself reading Adrienne Rich working in Emergency’. I’m working at the pool, finding myself here, mostly by myself, and calling it work. That is, I’m working toward saying something about the pool’s pull. And I’m working to figure out where I or anyone might want to work, and what place does to the kind of work (literary, emotional, social) we do. ESP’s book is not about work, working in Emergency, but about going to the pool after work, responding to the pool’s draw as a place to find oneself. She doesn’t put the pool to work. She wants to represent the pool. She does it through concrete poetry that depicts pool life and a pleasantly obsessional, looping pool theme in lyric poems that precede the concrete ones.

You build a pool because you build a nation. In the City of Melbourne, ‘Councillor Ken Ong, Deputy Chair of Major Projects, said the [Carlton] baths can be enjoyed by everyone, whether you’re a mother bringing your newborn in for a health check, a teenager coming in for a group fitness class or a senior community member visiting for a swim’ (2016). Is a community a nation? Is a microcosm a plan or a pattern and is it telling the truth? Ellena Savage calls the pool a ‘heterotopia’, a ‘(distorted) microcosm’ because ‘not all bodies are allowed entry, after all, and not everybody wants to go’. This refers to its value or quality, and unpicks the mythmaking of Ken Ong of Major Projects. It does not necessarily tell us about what the heterotopia does, what magical symbolic work. This is possibly the job of poets.

Ronnie Scott, writing about the filming of iconically Melbourne novel Monkey Grip taking place mostly not in Melbourne, notes that there can be a stronger ‘feeling’ of truth drawn out by copies and approximations, than by originals: ‘It undercuts the seriousness that forms around iconic things; it makes it easier to see the thing itself.’ The pool as a symbol of nationhood is more powerful than any more direct representation. Can a renovation be racist? Idil Ali reminisces about a childhood sneaking into Carlton Baths which was full of friends and family, parents in the spa / sauna (now gone, with the hostile reno) and the kids, it would seem, running wild. Why did they get rid of the sauna?

Where do we find ourselves?

Swimming and writing come together often enough in Australia, and Australian identity is often forged around metaphors of water (island nation, boat people), and images of watery folk (surfers, swimmers). Parts of Australia could be described as cultures of wasserluxus, a term used by archaeologists after Michael Jansen in relation to Indus Valley civilisations, including the Mohenjo-daro, which was home to the earliest known public pool, or Great Bath. Wasserluxus (‘water splendour’) refers to the ability to harness and share water on a luxurious scale for the use of all people, including for ritual purposes, and in modernity that ritual is leisure. Treating water as more than just a necessity, wasserluxus unifies society. Australian writers writing about water could be thought of as engaging in wasserluxus.

In modern urban pool literature, pools are often connected with healing and grieving, a sort of ritual site – as in Body Friend by Katherine Brabon. In Monkey Grip, the pool’s deep water is a metaphor for the deep shit Nora finds herself in, in love with Javo; the pool itself a metaphor for the narrator’s swirling social milieu. In Rachel Ang’s Swimsuit, the same pool is a setting for an awkward catchup with an ex, a stage where one’s body is up for judgement. In Christos Tsiolkas’s Barracuda, swimming is Danny’s ticket to upward class mobility, gained thru a ritual of competitive loneliness.

The timeless element of water tempts me to draw analogies: me in Melbourne; ritual bathers at the Great Bath. The pool and its special water is charged, pregnant. But also bland and null, empty space. I move thru it ritualistically. What are pools like in Japan? I ask a friend there. Blue holes in the ground. The similarity of water to water. And the magic of rectangles, bricks to build rectangular holes, and the bricks’ ancient thickness, width, and length ratio (1:2:4). Rectangular timeless form expands outward (8, 16, 32 …) toward infinity…

But the pool is also a problem: and water is actually different to water. π.O. reckons Garner fetishised the pool in Monkey Grip: ‘I was going to do a whole history of the pool in my new book’, he claims in a recent interview, ‘but I shied away from it because of Helen Garner… She’s always writing [in MG] about riding her bike and feeling so free. But the thing is, the working-class kids couldn’t really afford bikes. We couldn’t go anywhere’. π.O.’s ‘whole history’, in the style of Fitzroy and Heide, might dig into the social history of pools, into the minor histories of local councils and local peoples that produce this new thing – ‘the pool’ – as well as the larger currents of settler colonialism.

There are tough-love historical pool essays from recent years that politicise the pool and its relation to national narratives, echoing π.O.’s sentiments. Gavin Scott concludes his detailed summary of Australian pool history, titled ‘Aqua Profonda’, with a glib summation of Australia: ‘Each time we swim, we evoke the depth of Australia’s long and contested history – Indigenous, colonial, multicultural – of playing, striving and worshipping in and by the water.’ Savage’s ‘Everything Anyone Has Ever Said About the Pool’ acknowledges in its title the pattern of writers’ attempts to speak about the pool. Like Scott, she is at pains to show the pool is not ‘neutral’ or eternal, but has a political and cultural and gendered history. It is a volatile space where we demonstrate our faith in the state to keep us safe, where we willingly accept ‘fascist’ rules. It is a place we go to enact our protestant sense ‘that anything of value in this world should feel slightly unpleasant and always hard-won’. Savage’s essay treads the water of its own neurosis about being neoliberal, ashamed of her propensity for laziness and doing what comes naturally, while having, rhetorically at least, internalised a critique of neoliberalism, i.e. her intelligent and savvy essay about ‘the problem of water’.

But I’m not here to be smart and precise and historical. I’m here to bash my head against the thing of the pool, my pools, and Different Waters, and try to live inside the book’s production of the pool as a way to reflect on why I go there, why I think it might be a pleasant place to write. I go toward these rectangles, I let them do their work on me and slowly improve my swimming.

I engage in myth-making when I say ‘Fitzroy Pool’, ‘Carlton Baths’, when I name the pleasant place. Stories say: come under the surface of the text, into its world. Stories ultimately use the pool for a purpose beyond it. To tell a story. To make a point (about a nation). Poetry tends toward greater opacity. This opacity is perhaps at its greatest in concrete poetry. I am thinking that opacity in writing, even hardness, leads us toward mysticism and magic.

ESP does to the pool what narrative can’t: her poetry aligns itself with the visual patterns, petty minutiae, small differences, banalities – a focus that brings difference into relief via the grit of surface. The pool is not a setting for a poem, but rather is a poem. By making concrete pool poems, she partakes of pool literature in which the pool is figured as the antithesis or cure for writing, which we seek in moments of crisis or grief, and yet fails to satisfactorily account for the extremes of emotion. We meet the pool and go silent. The pool is silent too. ESP realises this silence not by writing, but by turning letters and punctuation marks into brushstrokes. It makes me think of Whitman’s invocation for the poet to judge ‘not as the judge judges, but as the sun falling around a helpless thing’ (‘By Blue Ontario’s Shore’). And in this non-judged position, the pool (and the reader) can breathe, and we can hear it.

By leaving out place names, by not fetishising specific pools, ESP pushes the pool onto a more abstract and mystical plane. In this way she gathers the mystical-romantic burden of poetry and symbolism with the flat bureaucratic blandness and petty bothers of corporate, neoliberal Australia. The pools in Different Waters are hard surfaces for poet swimmers, such as myself, to bash the old head against, to fall around as a helpless thing …

There are two pool poetry precursors to ESP’s project, both published by Stale Objects dePress:

Katherine Hummel’s Splashback parodies and extends the pool’s propensity for signs reading such things as ‘NO RUNNING’. I speed down the 250pp pdf, past as many signs in bold black on orange. The activities after these NOs – from ‘NO DIVING’ to ‘NO GENOCIDING’ – mostly follow each other because of some semantic or sonic link; they do not build a narrative. Hummel’s chapbook shows the joys of poetic thinking while at the pool, the pleasure of moving forward with little care, intuitive and animalistic. Is this a form of swimmer’s meditation? Or is the chapbook ‘about’ the bossiness of the public pool, the negativity of public language mocked by the anarchic artist?

Charged with up and down energy (NO and ING bouncing back and forth, the G’s curl forming a sort of arrow shooting the reader back to the phrase’s beginning), the pool is shown to be a site of containment, policing, safety, and order; of thwarted potential: potential danger, potential fuckery – potential evil but also potential fun. The positive charge is the poem made into a diving board which splashes into – no, not into, as – a critique of nationhood. The Australian NO: NO NO NO. NAUR!

‘No’ to and of the nanny state, and NO we’re not sorry. Just no. Sorry. Splash!

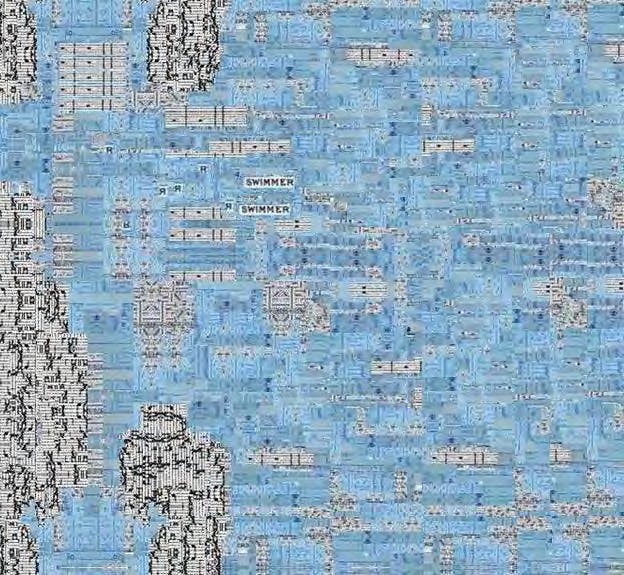

The more obvious precursor is Catherine Vidler’s lake labyl, a series of 71 concrete poems over the course of which we see a fragmented musical score become a glitchy, psychedelic ‘scene’ of a lake made of punctuation marks. Towards the end of the series, two figures, called(?) [SWIMMER], appear to move around the scene. lake labyl – the swimmers is a sound-gif (which no longer exists online) comprising the series’ final 17 images accompanied by Rachmaninov’s symphonic poem ‘Die Toteninsel’. In the absence of the original gif, you can listen to a recording of Die Toteninsel and watch the last 17 images on the SOd website.

The most legible text in lake labyl is on the first page, reading ‘Begin at either end, play either forw’ before being cut off. It recalls the piece of palindromic music or rondeau by Guillaume de Machaut (1300-1377), which inspired ESP’s poem ‘My end is my beginning, and my beginning my end’. The enigmatic phrase belongs to artworks (including perhaps T.S. Eliot’s ‘East Coker’) that enjoy riddles, ask to be read in unorthodox fashion, and, thru unsettling the ‘locomotive’ reading process, somehow point toward the infinite – the infinitely recurring?

lake labyl becomes gradually less legible, and less familiar than the musical score sheet it begins with, filling with splotches of light blue pixels and later splotches of blue made from punctuation marks. The blue arrives in patches early, gradually increasing its presence until the final frames are dyed blue.

It is difficult to ‘read’ these poems as things that make sound-units or that at least hint at a sentence. The visual analogy is strict: a series of keystrokes (‘X’ ‘#’ ‘&’ ‘[]’ ‘@’ etc) = the colour blue (= water). In this way they are almost silent, and poor guides to a ‘world’. They also fail as images: there’s no ‘view’ (or locus amoenus) to enjoy. Rather, you get sucked halfway in and squirm around trying to figure out what’s going on. You fall into them, and they are oddly silent. In this way, perhaps, the experience of reading them is like swimming: not a lot of sense-units, but certainly moving parts, some splashing sounds; I’m moving and the water’s moving, we’re trying to ‘get somewhere’ but we’re not really getting anywhere (we loop). They are hard things to swim in. A concrete poem doesn’t tell stories about human experience (like e.g. Garner’s novel). In this way we could say they treat the pool with more respect: the pool is not a stage but a THING … and it is this thing that I bash my head against.

Imposed on this almost-silence of Vidler’s concrete poetry, the grandeur of Rachmaninov’s music adds drama to the slog, and makes the figures in the visual field seem, we might say, ‘balletic’ (the writing here aims toward dance as much as image). Likewise, listening to the Machaut alongside ‘My end is my beginning…’ elucidates that poem’s pleading with the infinite. How is it that concrete poetry engages with infinity? I say, instead, that it encourages a sort of unpleasant lap-swimming; that lap-swimming (as a unique activity but also as an abdication of the writer’s – neoliberal? – responsibility to write) might have something to do with approaching the mystical.

‘Is a day enough…?’ ESP’s These Are Different Waters opens with a question billed as an ‘un-atomised fragment’; numbered ‘1’, it asks about the ethics of idleness. This particular day involves ‘sending two messages, going for a swim, making a soup & doing the crossword’. The ethical problem is that of being a witness to violence and not, or barely, acting. ‘2. The human rights watch articulates clearly on TV.’

ESP’s day sounds like enough if trying to feel good is the aim. The fact of the swim affirms it. Sitting on the couch with a crossword is enhanced by the pool factor, even amidst the swirling world of text messages, TV, and the internet. The poetic stance ESP seems to adopt here reminds me of David Antin’s talk poem ‘War’ (discussed and abridged on PoemTalk). In the wake of the Iraq war breaking out, Antin says he feels ‘a little bit like Archimedes’, interested in working out π. He imagines Archimedes drawing a series of overlapping polygons, as the Roman invasion advanced. Despite bad news all around, the poet ‘still wish[es] to explore patterns’.

And yet: ‘4. Something feels unwell, or wasted (time-sick)’. The pool provides protection (apotropaic endorphins {in dolphins}?) against the noise, the swell of language which in contemporary Australia tends to admonish, worry, and lie. It aids in the production of a locus amoenus, where she can relax with the cat and do the crossword, and write. The poet’s conundrum: ‘5. I do not wish to think about cutting into bodies, of bodies being cut into / 6. I still wish to explore patterns’. This is a bold way to start a book, but honest, and possibly hopeful.

It is a mode backed by Joan Retallack’s collection, The Poethical Wager. In its opening essay ‘Essay As Wager’, she writes that the value of ‘swerve[s]’ away from norms and the supposedly preordained is in their being able to ‘dislodge us from reactionary allegiances and nostalgias’. Retallack’s circuit-breaker poetics is against the ‘locomotive destiny’ of certain rhetorical models ‘embedded in nineteenth-century temporal arts’. ‘Wager[ing] on a poetics of the conceptual swerve is to believe in the constancy of the unexpected – source of terror, humour, hope’. This triad gives Retallack ‘energy’ to be ‘in motion amidst chaos’. Then she says, and this is ESP’s epigraph: ‘This motion [amidst chaos!] on the page is analogous to that of a swimmer who takes pleasure in the act that also saves her from drowning’.

Finding the overlap of pleasure and survival is the ethical stance Retallack seeks, and presumably ESP too. The super-pleasure of ESP’s swerve might be a move past Retallack’s essay (which is very much not about swimming), breaking its pattern in order to see something about her own life and poetics and desire to contemplate patterns, and to go for a swim. To break the circuit/pattern of American circuit-breaking poetics with a big mystical wave of Australian pool water, and swimmer-poet’s goggles on…

What are we doing here?

I’m trying to find the locus amoenus; this is my current pattern problem. How to have a lovely day, and how to read and write during Melbourne summer. I’m trying to respond to my environment, or I’m trying to build the best one. It’s a beautiful day, after a few hot ones and a bitsy stormy cool change. In a lounge chair at my house, getting sun drunk, I start to get anxious. Go inside for sunscreen for arms and feet. When I have time on my hands, I crave a pleasant place and go to it.

The locus amoenus is a pastoral place. The pastoral is a naughty genre. In contemporary Australian poetry, it tends to come with a caveat: ‘anti-pastoral’. The contemporary poet likes to be against things. I find it easy – in guilty moments in the locus amoenus, but also generally, as a way of undercutting the value of poetry’s ‘pointless’ work – to think of it as a pastorally-coded (dole-bludging) activity.

Brian Blanchfield’s essay ‘On the Locus Amoenus’ considers whether ‘the poet is different from the person who writes the poems and pays the Comcast bill late again and gets balsamic dressing on the side and snaps at customer service…’ That is, when the poet-Brian speaks, ‘why does [it] not sound like how you talk’? Because the poet ‘is made the poet by the poem, each poem’. This poet is ‘someone unnamed saying something to someone unnamed, either in a particular context or in the realm of forms, I am not him, and I want you to hear it’. It is a place where ‘all the looking is onlooking’, and presumably there are no bills or balsamic. There might be water; it might be crystal clear.

If it’s possible or even likely that I am not me when I write a poem, what does it matter what or where the locus amoenus is IRL? It seems logical enough to say that it doesn’t. And yet I go to the pool. And yet writers like ESP’s witchy American idols, in particular CA Conrad, make a case for the obvious and eternal importance of IRL spaces, the felt symbolism of worldly materials that help produce poetry and feeling.

The locus amoenus is hard to find, and it presumably always was. It could be the calm aftermath of a time or place of distress and disorder. It could be having enough money: ‘One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well’ (Virginia Woolf). It could be being a baby. It isn’t war, but neither is it peace that is aggressively imposed. The locus amoenus is either/both historically contingent, or/and a timeless, universal nostalgia. Or is the longing for a pleasant place not nostalgic, but utopian – a vision of a constantly deferred tabula rasa where all the drama of history subsides and makes way for – what? Pure noise? I hear the pool. It could be the public pool: the real public pool, or the public pool of official and unofficial fantasy. At the pool, you remove yourself from your ordinary context, and you clear your head. The clearer head is the locus amoenus, isn’t it? That very metaphor, clear, tells us so.

The desire for a pleasant place from which to speak is a desire for no history. I wish I had it. No I don’t. I hate having fights when I’m running on empty. I can’t write poetry if I haven’t had a good night’s sleep (is that neoliberal?) I hate suffering but am gluttonous for it. I tell a class of undergraduate students that rhymes and sonic associations are important, are one kind of ripple. What about this: At the pool I pool my resources. I pool, and you pool too. Time is running out. When I pool with you, we compare kicks; when I pool with you, I feel scrawny and lame. When I pool with you, I admire your whole person. I put on my shoes on the astroturf. There are little brown leaves falling now.

The flimsiness of the locus amoenus under consumer capitalism is symbolised by the INFLATABLE POOL, conveniently enough the title of the first section of Different Waters. It comprises mostly lyric poems, whose speaker seems to inflate herself, her ego, from a position of neurotic worrying (about poetry?) to one of confidence and magical power. The first poem, ‘Avalon Airport/How to Unatomise the Fragment’, again, starts from distress at feeling ‘atomised’ (or is it anxiety about texts being fragmented?) and proposes a general desire for unity. It is also a puzzle, a crossword-like game. To be atomised is to be neoliberal. Are fragments neoliberal? What’s the difference between an atom and a fragment? ESP paraphrases Schlegel: ‘37. Ancient texts are made fragments by history, modern texts by design.’ But! ‘38. This is not fragmentary’. Fragments are sharp broken bits; they can hurt. Atoms are free-floating and round, like inflatable pools – pop! The numbered lines in this poem help to atomise (or is it ‘fragment’?) what could mostly be read as a lyric whole whose lines continue, more or less ‘naturally’, into each other. They enact the anxiety the poet hopes to dispel when asking, ‘Is a day enough’?

The line break’s new breath can be thought of as, yes, a swimmer’s lap, and also a pursuit of the locus amoenus, a feeling (hard-won) of newness and freedom. ‘I am’ is repeated at the beginning of four of these lines, while ‘I’ begins another six, as if placing the speaker in a new locus each time, trying to reinstate that pleasantness of arrival. It is a way of ‘finding oneself’ (I am here). What can poetry do: twirl, loop and breathe, and in the process demonstrate the stupidity of neuroticism. Oh, what on earth is it to be unatomised, as a text or as a person? I am… I am… Just breathe…

The poet of INFLATABLE POOL gradually gets over this fuss about being unatomised. Reading this section of the book, we see her gather strength, via stories, patterns and talismans, plunging again and again into the poem’s water. The final poem, ‘A Small Bath’ starts with the speaker putting her head ‘an inch’ underwater to deal with some unexplained pain. This shallow pool becomes a birdbath, then it becomes a larger pool, then ‘it is salty and unending and I know I am in the ocean’. ‘I have arrived’, she says at the end, ‘yes I am here’.

I’m at the pool and I can’t believe the prestige of these swimmers. Fitzroy, 5pm, 20 degrees and sunny. I’m on a blue chair with a view of the iconic steps. Everyone is freestyling. I have to get in.

If the first half of the book was about ego inflation and the pursuit of ‘unatomisation’, the 25 untitled CONCRETE POOL poems are about ego death or self-dissolution within patterns: the pattern of lap swimming, and visual representations of that hectic multifarious scene.

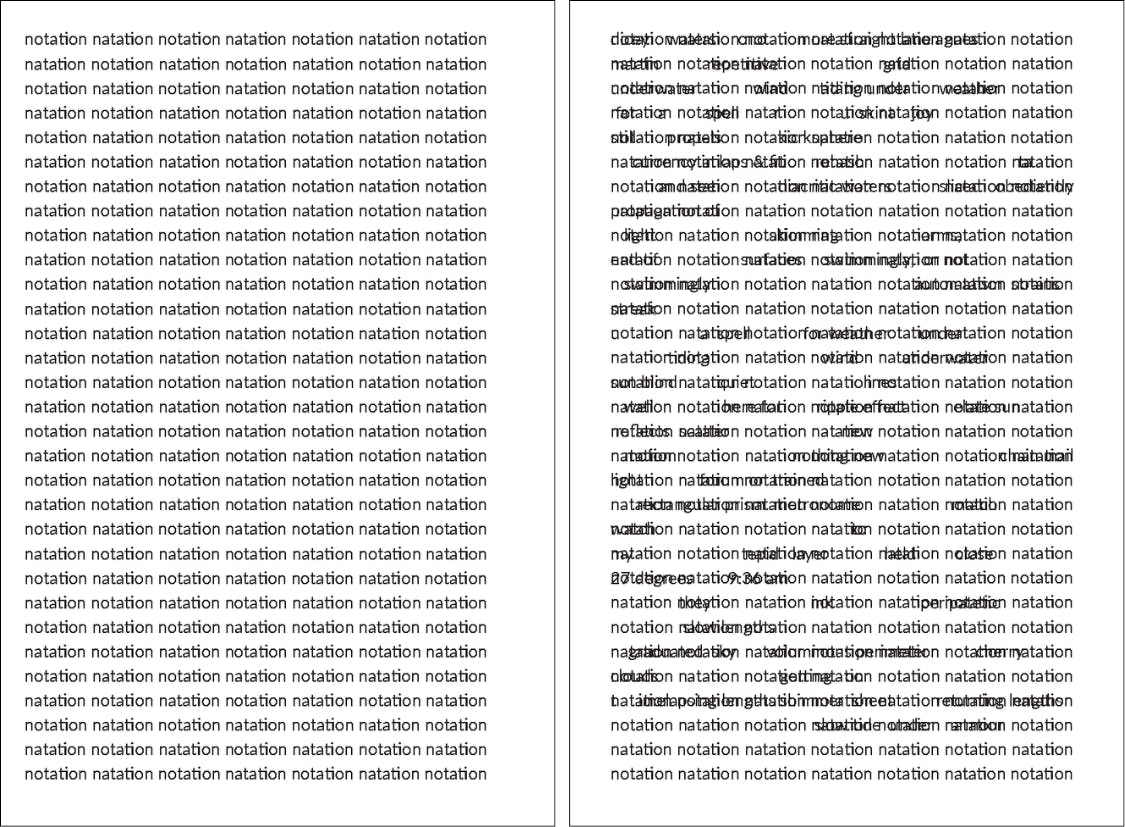

Words themselves lose their message to become part of the medium. The gridification of words destroys their bonds and forces us to see past(?) narrative and semantics (pools as heterotopias) into surface aesthetics. I think of aj carruthers, who circles this essay like a shark, writing on Jackson Mac Low’s ‘austere’ poems: ‘what we are doing now is not just reading but viewing, not just binding signifiers together, but breaking them apart. It puts space between them so we can really see each word for what it is’. ‘CONCRETE POOL II’ is neat, the words acting like words in a line, pointing up, the happy coincidence of ‘notation’ and ‘natation’, two words differentiated by a letter, or the slight curve of a line that squishes an ‘o’ down to an ‘a’. (Or is that emergent curve, swerve, a baby swimmer’s arm poking up to say hey!?)

‘Natation’ pushes me back in time. It comes from Latin natare, to swim. The English word, ‘swim’ comes from a Germanic root; the Greek word νέω (náō: to flow, to swim) seems to me linked to the prefix ‘neo’, also Greek, i.e. νέος – neîos). Poets love the happy coincidence of etymological links. I thought of another: ‘natare’ → ‘natal’, birth. Both ESP’s words are Latin-rooted (were there poets writing Roman-bathside?) but the first pool, the Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro, was in modern day Pakistan, built in the third millennium BCE.

In Mohenjo-daro, archaeological digging shows private houses had bathing facilities. The Great Bath, however, was separated from the vulgar affairs of the town, situated on a mound, and used probably for ‘ritual’ bathing; its height and separation from city life is where the ritualness comes from, in archaeological interpretation. It measured about 12x7m, and 2.4m in depth. It was made from baked brick with a waterproofing bitumen layer. It was, like ESP’s pools, a rectangle. The dependence on baked brick to do a bathing ritual strikes me: it is a tricky mysticism that hews away from Nature, beloved of Romantic poetry (see Byron’s swimming ritual). Not a perfect clearing or sublime extreme, it closes itself against the landscape. As a locus amoenus, it is more like a church.

The baked brick stands out to me as important to the pool, and to Different Waters’ search for patterns. That the Indus Civilisation spread this technology of uniform rectangular bricks, which literally changed the world, is a powerful pattern. Their rectangular nature maps on to the pattern-work of concern here. We echo it. Pools and poems and bricks lined up, analogous: what does a rectangle do? Modern pools are made of concrete, but lined with brick-like tiles, continuing the ancient pattern, plus colour. ‘the blue is waking me up’.

If the words are bricks, there are both strong and weak examples to touch and consider. In ‘CPIII’ the words begin to overlap, creating blurry burrs in the ‘notation/natation’ pool. The repetition of these two words works like a spell to align swimming and writing, ‘notation/natation’ are baked bricks on the pool’s floor. Influenced by water, they begin to climb on top of each other so as to be indistinguishable. Overlaid, they become illegible, making stains on the page rather than units of ‘sense’.

The rectangles of brick-words that make up a number of ESP’s CONCRETE POOLS are both hard and porous things for readers/swimmers to engage and think with. In ‘CP VI’ the serviceable bricks/words ‘notional’ and ‘national’ create a pool’s perimeter with a void at the centre, an empty pool. This rectangle is watertight but, perhaps, like a pool in The Sims, a place where lacking a ladder Sims go to drown. Its empty centre is a place for dreaming, projection, play – a blank slate or terra nullius? But no one is in it; it’s a lonely fantasy or a fantasy of being alone, of an empty nation (a locus amoenus?). The notional/national dyad (dryad??) reappears in the eighth pool, which has been sliced horizontally thru the middle. A broken rectangle is less claustrophobic but useless: water would just spill out. As with ‘notation/natation’, we overlay the terms to say that Australia is a notion. It places the (notational) nation in the setting of the pool, as do politicians, and as we know water wets the word. This is the conceptual poem’s fuck you to so-called Australia. But I think their monolithic quiet encourages a deeper, more open interpretation than this glib ‘political’ one. That is: consider the rectangle.

At the pool in inner Melbourne, people read books. Today it’s bell hooks and Natasha Lunn. I see (tues, grey sky, 32°C) a father’s hairy plumber’s crack; the Natasha Lunn reader’s Insta feed. We come here to slay. The best swimmers are the oldies in flippers going backwards. I don’t feel like swimming – I want to pop! Red grapes and babies on towels and rugs. ‘Say have a beautiful day,’ a man instructs his baby. Yesterday at the carnival some kids were so good at swimming! but the day was so boring! So much standing around and waiting. Swimming is too personal without television, the scale of its drama is private. Shit, I forgot my goggles.

ESP does pool theory and so reading her at the pool makes me self-conscious – and potentially supercilious. I’m not reading bell hooks or Natasha Lunn or Alain de Botton. The pool is not a backdrop to my grandiose (neoliberal?) self-work. I’m reading these poems that think the pool thru, crossword-like; the poems act like and contain clues. They excavate the raw materials of poolness to become sort of magical objects, maybe. I’m saying they bring the pool to life despite self and stories not mattering: patterns matter, and patterns are the stuff of life.

What does ESP mean by ‘patterns’? One example is the pattern made by the sound of neighbourly houses (‘Dusk, George St’), overhearing conversations, recipes, cats, smells. Recording ‘everything’, the poet has to open herself up to chance. ‘Is happiness the name for our (involuntary) complicity with chance?’ (Lyn Hejinian) There is a calm happiness to writing poetry that is humble in scope.

There are poetic patterns like a rondeau or a pantoum. ‘Cat’s Pantoum’ facilitates for ESP a place to play with rectangular shapes of four-line stanzas up against a cat’s curled up oval shape. The poem’s ‘[c]ircularising’ rules force her to wind up the poem like the originary cat’s curve. The concern with pattern is invoked: ‘To want the same but different order / Circularising modes of attention’. Doing the crossword or watching the cat sleep is definitely not neo-liberal. Asking, as we might, is it enough (to be/warrant a poem) we can watch the poet’s solemn, almost menial task open up into the transcendent quiet of repetitive and ritualistic artworks like mid-twentieth century American conceptualists, Agnes Martin or Mac Low, about whom ESP has written for HEAT: ‘To read the poem is to chew it, to be alive to sound and language’. Asking is it enough we can catch ourselves speaking in the voice of neoliberalism. Staring at the cat pantoum and the concrete pool we can be free. Chew on the pattern of the world.

A mother leans back on her elbows to take photos of babies in a pattern on a patterned rug on the grass by the concrete by the pool as water BLASTS something metallic and large behind a beige fence. A train hoots past. The sky is still grey and white. I imagine if I bought flippers I could swim for hours on my back hugging a kickboard like the oldies who come here at dawn and at dusk. Like an otter, my favourite animal as a boy. Now that I think of it, I feel like I could double pool today (nursing double forehead pimple, double mouth ulcer). Bizarrely, a magpie swoops the patterning mother (Feb 28th). I finally spill a drop of water on Different Waters. It was a droplet of rain.

The mystical rectangle in Different Waters folds into the final ‘CONCRETE POOL’, and the end of the book, a short lyric poem that shows a strong ‘I’:

I’m going my fastest when a hand hits

my foot

I’m in

the medium lane and you're wearing

hand paddles

Come on

I’m trying to enjoy the show

Check out those blues

They’re stunning

The word ‘show’ implies spectacle or performance, a distance from the object (squad swimmers, blue tiles) and a conversion of their hard deep work into something sold – a view, an approximation or microcosm of Australian greatness (cf. the Olympics, which also harks back to antiquity). The book ends on this simple image of the pool’s stunning blues, bringing us back to the cover, too, which features six watery blue watercolours by the author. This is the watery spectrum of Different Waters. Blue makes a difference to itself. Blue like out of the blue. Out into what?

Come on

I'm trying to enjoy the show

Hard day yesterday, some damage (and growth?) … A worker at the gym recently explained that in a workout the muscles are tearing or breaking, and then regrow stronger, that’s how muscle is built. I didn’t kno this science of exercise, tho it explains the pain you feel afterwards, and how it’s not always bad to ache. It seems ripe for an essay like this, or what this could be, or what pool essays often mostly are, guided by a metaphor of growth enabled by the holding pattern of the pool. In ‘On Coherence’, Brian Dillon writes that when an essay finds its ‘guiding metaphor’, it almost ‘write[s] itself’. I keep finding myself …

8am pool sesh is my personal best. I’m going to come here, I said this morning, to write. The grass is still dewy from last night. I’m saying hi from the pool, hello. I love you because I grow here. I make a meal of my one life and eat it. I drip chlorinated water onto my book, my writing, and write around it. (‘Thorpey’, it occurs to me occasionally, ‘says the taste is fully sick’). Water makes a bracket. In ‘CONCRETE POOL XV’, ESP makes the bracket into a ripple, a swimmer’s stroke. I call it a talisman and give a sort of thanks. I want to learn to go slo like the oldies but I am young and strong and when I meet a hard limit I pick it up and drop it like a little brittle brick.

I swam twenty laps and now I’m here, slightly more vital. The pool is like a power station: we come here in the morning like electric-powered cars. Watching the sun brighten. Do you see the sparkle on the water’s surface? All the long winter I waited for this. I lie in the sun, I follow rivers. Listen to the sound of the kids’ pool-splashing fountain. I bash my head against the city’s ecstatic poem, these blue holes in the ground. I invent ecstatic poetry, what ecstatic poetry is (sparkling water and typos) I don’t believe in meaninglessness. Everything is sacred even ‘ten more laps’ even at work I feel eventually emotionally intense now. Punctuation is serious and sacred too, that’s why ESP makes it a pedestal, a whole page. A curved line like so many things (its potential flowers out in its pedestal silence): an arm, a windscreen wiper, a belly bulging, a penis lolling. The pool is a pedestal for me to bash my head against the morning of my self, a performance for you too so that you may feel it.

All my adult life I’ve wanted to arrive at a stronger future self. But now I see the folly of this; that life is a series of trials and then you die. Why talk about death when talking about the pool which is a womb. Is it? An essay or let’s say a text can light up when a metaphor seems to complete itself. To arrive. This essay is hard to finish because it wants to dance on the grave of its potential metaphor. Would life or ‘it’ be easier if I just let the pool be perfect instead of pointing like a baby to the oblique mysticism (possibly of my own imagination) that sits in the wings of ESP’s book and my public pool experience? Why can’t I just make a neat solution to the problem of pools and why we go there, why they become places that we ‘need’. Why can’t I tick the pattern … lick the pattern?

May 1: Melbourne bright blue, wearing my bright blue baseball cap. Listened to ‘Drover’ by Bill Callahan eight times on way to pool last night, last swim of the season. Straight from work. I hadn’t thought about that song for years, but its strong short tripartite chorus jolted me. Are horses connected to the pool? The land belongs to the cattle. This jolty triangle, North Melbourne Pool, to whom does it belong? Afterward walking to North Melbourne station behind a tall dark and handsome drover-like man, I’m singing loud along with my black headphones in motion against chaos: something about this wild wild country makes a strong strong, breaks a strong strong mind … but anything less anything less makes me feel like i’m wasting my time.