La lutte elle-même vers les sommets suffit à remplir un cœur d’homme. Il faut imaginer Sisyphe heureux.

The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

Bullet, Paper, Rock: A Memoir of Words and Wars

Sydney Review of Books are pleased to publish an edited extract from Abbas El-Zein’s Bullet, Paper, Rock: A Memoir of Words and Wars, out now. Read now via the link in our bio.

This is an edited extract from Abbas El-Zein’s memoir Bullet, Paper, Rock: A Memoir of Words and Wars out now. Published with permission from the author and Upswell Publishing.

Lexicon of Love

Arabic speakers are spoilt for choice when it comes to expressions of love. At least twenty-five Arabic words for different shades of love, affection and love-induced states of mind are in common usage, by my count. The actual number is said to be somewhere between fifty and one hundred, if formal Arabic words, less encountered in day-to-day speech, are included.

hub, hawaa, gharaam, walaa, hanaan, shaghaf, kalaf, shawq, walah, tatayyum, haneen …

No two words have the same meaning, and the vocabulary maps out a range of emotions, moods and relationships with the beloved, while conveying myriad kinds of love – sensual, carnal or chaste, profane or divine, joyful or melancholy.

From love as tenderness (atf or sababa), forlornness (wajd) or feelings of warmth towards someone (wod), through chaste (eeffa), eternal (rasseess) or unrequited (lajaa) love, to adulation (oshq), infatuation (wallah) and passionate love (hiaam). Love that leaves us burning is huraaq and love that stings is lathgh. There is suppressed love (kamad), love as joy and enjoyment (miqqa), love as peaceful surrender (istikana), love as intimacy (oulf) and love as seduction (foutoun). There is of course love as intercourse (nikah) and love as eroticism and licentiousness (ibahi). There is a word too for the prestige that a man draws from loving, and being in the company of, women (tashbeeb). Shawq has been likened to the Greek ‘eros’, ‘insofar as it was taken [by the mystic Muhyieddeen Ibn Arabi] as a fundamental driving force within human life, art, and thought’.

The word jawa refers to the alternating states of hope and despondency that a lover endures. Love that leaves us terrified and transfigured is wahl, while sabwa denotes nymph love and love for a younger person – it comes from the root words sabi for boy and sabia for girl. Some words have dual meanings, one of which works to reinforce the other: jounoun is both madness and love-as-madness – hence the famous Majnoun of Leila, also known as Qays. Lathaa is the way a flame audibly climbs up and consumes a dry piece of bark, but also means scorching love; halaak is extinction as well as fatal love.

In a surviving compendium of around 7,000 books from tenth-century Baghdad – called Kitabu’l Fahrast, compiled by Abu al-Faraj Ibn al-Nadeem, and providing a snapshot of medieval Arabo-Islamic literature – ‘no less than a hundred (are about) love’.

I don’t recall as a child ever hearing my mother or father, uncles or aunts, sisters or brothers, telling me ‘I love you’; neither was I expected to say it. In the world in which I grew up, only lovers on TV or cinema screens said those words to each other. But I never felt the need for such direct assertion, because I never doubted that my family loved me. Love was conveyed to me in little gestures, subtle dispositions, and dozens of other words – habibi (my dear or my love), omri (my life), rouhi (my soul), albee (my heart).

When addressing her children, my mother would routinely add ti’borni (‘may you bury me’, as in ‘may you outlive me’) to her utterance. Inevitably, this over-the-top expression drew ridicule from her grown-up children. To be fair, it was just a culturally convoluted way of saying ‘may you live long’, a habit of speech my mother had acquired from her rural upbringing and never abandoned even after moving to the city. But we, her children, urban to a fault, would not let nuance ruin an opportunity for a laugh.

Terms of endearment were always said in passing, sometimes with a little irony – ‘Pass me the salt, ya rouhi’ – but without the slightest drama and, unlike ‘I love you’, never calling attention to themselves or trying to be at the centre of the utterance. They emanated from naturally fierce loyalties and were hardly noticed except in reflective hindsight.

So much so, ‘I love you’ has come to acquire a particular connotation in my mind – smaller, a little hidden, and living alongside its bigger, sweeter and more comforting sense. Hearing those words brings up the possibility of their negation, of growing out of a world of all-encompassing love. It is as though a fish is being reassured that there is plenty of water in the ocean, not to worry, and so is needlessly reminded that there is indeed a world out there made of air, one in which it would suffocate.

This loss of innocence is not, of course, necessarily bad. That water, air and love are not omnipresent, not to be taken for granted, is knowledge we all need to acquire as part of growing up and growing strong. Nevertheless, I have inherited from my childhood this residual sense that hearing the direct reassurance of love in words, soothing as it is, is also a reminder of the possibility of its deficit, of a certain fragility inherent to the utterance. It is as if ‘I love you’ is always followed by a ‘but’ – small, silent, but no less real.

Lingua Franca

Growing up in multilingual Beirut – a few hours away from Europe, North Africa, the Arabian desert and the Indian subcontinent – I was immersed not only in several languages but in their politics, idiosyncrasies and hierarchies as well.

Lebanese was an unmistakably Arabic dialect that took words from French, English, Italian, Turkish and Persian, arabising their pronunciation and effortlessly adding them to its vocabulary. The most charming manifestation of this absorptive capacity could be found in the working-class lingo that gave us such gems as ashakmen (from the French echappement, for exhaust), trunshkot (for trench coat), wa la doomare (from the French pas un demeurant, meaning deserted). Or the Turkish aywa (yes), oda (room) and gazuz (fizzy drink). No self-respecting backgammon player would use Arabic numbers for the dice, but rather the musical Persian terms – hab yek, shesh besh, doubara, banj w doo, doushash, dabash – indissociable in a Lebanese mind from the sound of dice on the wooden board.

This openness to foreign languages was due in no small part to the fact that Lebanese was mostly a spoken dialect. It did not therefore face institutional barriers that written languages usually erect against adaptations from other languages. By contrast, the formal Arabic that we wrote was far less open to neologisms.

In the social world of middle-class Beirut, Arabic was seen as an archaic language, unable to engage with the modern world and its complexities. True, in many social circles, including that of my own parents, speaking good Arabic was a sign of authenticity, an antidote to the charge of colonial mimicry easily levelled against those Lebanese who used French in everyday life. But while an anti-colonial aptitude might earn you some admiration, it did not usually help you in job interviews or win you plaudits in high society.

I spoke Lebanese Arabic at home. Arabic was not only my mother tongue but the sole language that my mother spoke. Bookshelves in our house were filled with Arabic books, ancient and modern, and my eldest brother, father, grandfa-ther and great-grandfather all wrote professionally in Arabic (as journalist, legal scholar, historian and religious cleric, respectively). Respect and appreciation for Arabic was instilled in me from an early age, a healthy counterweight to the disdain prevalent in the world outside my household.

In the Mission laïque française schools where I was educated, the ethos was as Gallic, secular and authoritarian as the name implied. In high school, science and math subjects were delivered only in French, sometimes by French teachers. But when it came to humanities and social sciences, we studied two curricula in parallel, one in French and one in Arabic: two sets of subjects for each of grammar, writing, literature, history and geography. Mercifully, the difference between the two sets of subjects was not just in the language of instruction: they also covered very different content.

Inevitably, our teenage minds engaged in a comparison of the two languages and Arabic did not usually fare well. The teaching of Arabic literature and grammar, in particular, was boring, unimaginative, often requiring rote learning. Arabic literature at school was either ancient poetry, whose concerns could hardly resonate with us – love-torn Bedouins, feats of chivalrous knights, the stuff of courtly literature – or the modernist Lebanese texts of Gibran Khalil Gibran and Mikhail Neame, whose mix of spiritualism and Lebanese patriotism many of us found unappealing. Gibran and Neame, our rebellious teenage selves suspected, were second-rate writers sanctioned by the new Lebanese state because every nation needed its canon.

Against the material offered by our French literature teachers – the exquisite verses of Baudelaire, Rimbaud and Verlaine, the adventurous writing of Huysmans, or the gripping stories of Zola and Camus – Arabic literature, we came to believe, stood no chance. We had some inkling, but not much, of the murky colonial associations of some of the French writers we admired – the ambivalent settler politics of Albert Camus or Rimbaud’s arms dealing in Abyssinia. The curriculum that my school followed mostly swept these uncomfortable truths under the table, in an unreconstructed take on history that I would later discover was characteristically French.

While we appreciated some of the Arabic poetry we were taught, a good proportion of the classical Arabic literature we were exposed to was written in a flowery style, with an excess of adjectives, adverbs and silly rhyming, which we found insufferable. By contrast, we duly admired the conciseness that our French-language, and later English-language, teachers taught us to appreciate.

As for science, it almost went without saying that for our impressionable minds Arabic was unsuitable for scientific communication, a conclusion we succeeded in reaching with-out reading a single scientific paper in our mother tongue.

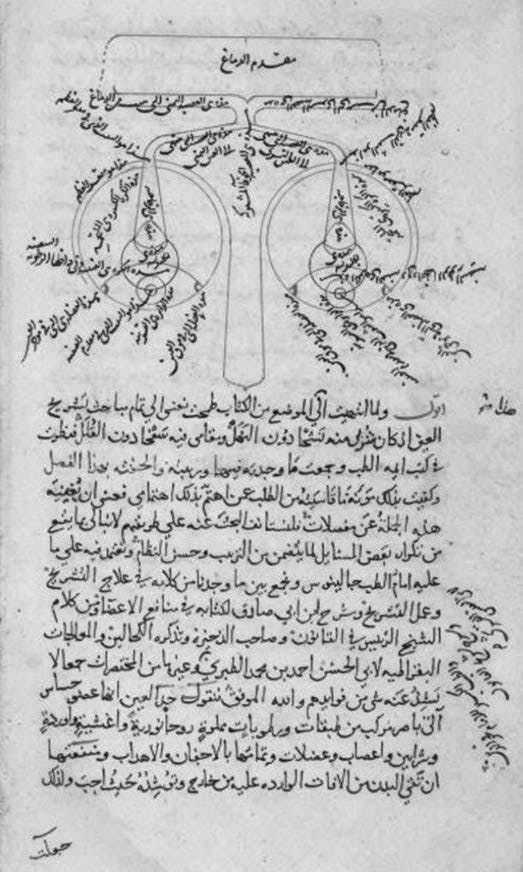

Extract from Kamal al-Din al-Hasan ibn ‘Ali ibn al-Hasan al-Farisi, ‘The Book of Correction of Optics for those who have Sight and Mind’, partly based on Ibn Al Haytham’s work, Persia, probably Tabriz, dated 708AH/309 AD, Sotheby. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. ‘Tanqîh al-manâzir’… New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Only much later would I begin to understand that ancient texts, whether in Arabic, French or English, had to be approached with a different sensibility and interpretative mind to more contemporary writing. What’s more, there were plenty of far more interesting classical, as well as modern, Arabic texts that we had not been exposed to, some of which had been gathering dust on my family’s bookshelves at home. That, in other words, I had attributed to Arabic literature a flaw of the conservative Arabic curric-ulum adopted by the Lebanese state and my own school.

And it would be several decades later, in Venice of all places, that I would come across an extract from the pioneering treatise on optics by Ibn al-Haytham, who was born in Basra in 965 and died in Cairo in 1040, in which he elaborates his theory of eyesight in Arabic, in one of the most disciplined, and altogether beautifully expounded scientific theories, I had ever come across.

I would discover that, rather than being prone to over-em-phasis and protraction, or incapable of supporting rigorous, to-the-point writing of complex scientific ideas, Arabic had a striking conciseness intrinsic to it, in comparison with the two other languages I spoke fluently. But this I would have to find out for myself, long after I left school.

Tongue Tied

I am sitting on an almost empty bus heading to central Sydney when my son calls me. He is doing an Arabic subject at university, and he has an assignment to submit the next day. He has texted me a page of writing that we are discussing over the phone. He’s uncertain about a few words and some grammatical constructions. Is ‘sunset’ shurooq or ghuroob? How do you say ‘train tickets were expensive’? And what about ‘I love going to the city’? Is it bil-madina or ila’l’madina?

It is mid-afternoon and, shortly after I pick up the phone, around thirty schoolkids, mostly teenagers in uniform, board the bus and quickly fill it up. I am still deaf in one ear, and my speech tends to be louder than average but not overly so – I know this from experience, even though I do not usually hear myself being loud. I notice some glances in my direction, every now and then. Those kids who seem to have noticed the conversation appear curious but not hostile, probably trying to work out what is this language I am constantly switching to in between my English sentences. I realise that I am being more self-conscious than I need to be. I chide myself for my innate caution, that I should be so mindful before speaking my own mother tongue.

There is of course a context to my self-consciousness about Arabic. Some of the more publicised instances of aggression against individuals from visibly or audibly Middle Eastern backgrounds have occurred on public transport. Head-scarves ripped off women’s head, individuals verbally abused as they sat alone minding their own business, men forcibly removed from aeroplanes before takeoff because other passengers had been spooked by the Arabic they were speaking, reading or texting. In the minds of many, September 11 transformed Arabic into an enemy language.

Buses, trains and planes bring people into close proximity, and can make for intense encounters because passengers are in each other’s personal spaces, either looking at each other or, more often, actively avoiding doing so. Our social interactions with strangers carry a latent threat of violence – even if most of the time we are not conscious of it – that we manage pre-emptively, through conventions about gaze, body language, and rituals of politeness and greetings. Growing up in the lawlessness of civil-war Beirut has left me with an added awareness of the ease with which the apparent civility of daily street life can give way to outbursts of tension, discord, even bloodshed.

I am a university professor, fluent in English, and while I still sometimes encounter racism inside and outside my work-place, it is rare, often subtle, and I am usually able to deal with it. I am fair-skinned and, like many dual nationals who migrated to the Western metropolis a long time ago, I do not stand out in public as particularly Arabic or Middle Eastern.

But my alien self can sometimes be heard. It is only when I speak Arabic or utter some Arabic expression, or when my name or that of my children is pronounced, that my other identity comes to the fore and becomes known to strangers. Each time I speak Arabic in public is therefore a watershed moment – low-key but dramatic – in which I have a sense that I am exposing myself to potential hostility. I work hard against this visceral affect and almost always overcome it, refusing to be cowed, insisting to myself on speaking Arabic in public, if and when it is expedient.

But something gives. Speaking Arabic becomes a small act of defiance in my own mind (and I suspect almost always only in my own mind) that robs me a little of the spontaneity of a mother tongue. So much so, I sometimes feel I am engaged in a double restitution – from the prejudice inflicted on the language by the world, and from my own self-consciousness when speaking it.

Rhm

The word for ‘mercy’ in Arabic is rahma, from the root rahm, for ‘womb’. The two most commonly cited of the ninety-nine names of God are rahman and raheem, commonly translated as ‘most compassionate’ and ‘most merciful’, sometimes ‘most gracious’.

The Prophet Mohammad is reported to have said: ‘God says, glorified and sublime be He, I am the rahman and I have created the rahm, and I have drawn a name for her from mine, so that those who stayed bound to her, I am bound to them, and those who break with her, I banish.’

What is this bond that God speaks of, and how does one keep it once the umbilical cord is severed at one’s birth? Will God turn his face away from me, now that my mother is no longer? Or did He already do so a long time ago?

Once Upon a Time

It is mid-autumn, just past midday, and still unseasonably hot. I am travelling from Beirut to Zahle, in the Beqaa Valley, an hour or so away, on the road to Damascus. It’s an eastward journey away from the coastline, through steep roads, snaking up Mount Lebanon. Every now then, the Mediterranean shimmers into view through the gaps between buildings, both sad and reassuring, like a former home that can no longer hide its fragility from its children.

My driver is a chatty thirty-something man, but I am still a little jet-lagged and not in the mood for small talk. We are having a one-sided conversation about ‘the situation’ in the Arab world and the dire state of the Lebanese economy. He treats me to an inventory of all the problems the country is facing – the falling lira and soaring cost of living; how difficult it is to make ends meet, let alone marry and start a family; the number of beggars on the street, ‘not just Syrians anymore, even Lebanese, would you believe it, who have never begged before’; how hopeless and corrupt our politicians are, how difficult it is to dislodge them, how we are heading to a catastrophe that only God can prevent …

The emotion in his voice has risen a little with every new item on the list. At least, I tell myself, this is a monologue to which I do not have to contribute; and all I have to do is sit tight until the storm has passed.

But then, unexpectedly, he looks at me in the rear-view mirror: ‘What do you think will happen, ya istez?’

Istez is an honorific that means all of mister, sir and professor.

‘Ma hadaa b’yarif,’ I say flatly – ‘Nobody knows’ – deter-mined not to add fuel to the conversation.

‘Shee bikaffir, ya zalami’ – ‘Man, (this is enough to) make you lose your faith (in God)’ – he replies, taking his eyes off me, giving up on his recalcitrant passenger. I have been demoted from istez to zalami, but at the least the pressure is off.

Shortly after, we stop in Shtoora. I wait in the taxi while my driver disappears into a shop to buy areeshe w assal, the cream cheese and honey the town is famous for, and I relish the silence I have been craving. The air outside my window is hot and humid; the seats are hard as wood. The trees lining the road are sun-stunned, their leaves drooping, the vivid green of their shoots long gone. The road reeks of molten rubber, memories of its potholes still fresh in my bones.

I try to doze off, but my mind is too alert. I find myself playing with the detritus of words that the gods of this land, long dead and gone, have left behind – eeman and amaan, silm and istislaam.

I, unconverted, unenchanted, savour nonetheless those words and contemplate the sweet, all-too-secular pleasure of giving up, of letting fate have its way with one’s body, as it had done with God’s. Of allowing myself to bid farewell, at long last, to the unloved century that has made my world. To give in, almost, to the ancient waves laying claim to me, like I almost did, once upon a time, a long time ago.

My driver returns, starts the engine and drives off, wordlessly. My mind’s eye settles on the faded colours of summer, now streaming past me. I search in myself for hope, but the quest requires discipline, and the banishment of distractions, not least the interrogations to which my mind likes to treat me every now and then.

What is hope, where does it come from and what is it made of? Is it a gift of individual temperament, an emotional state, or an intrinsic feature of reality out there that one must learn how to find and nurture? Is it a force for good, a self-fulfilling, self-actualising form of energy, or a feat of human make-believe, almost always bound to be cruelly disappointing?

‘Abandon all hope, all ye who enter here’: what does the injunction, in Dante’s Inferno, amount to? Is hopelessness a sine qua non, or even the very substance, of hell; or is it just a symptom of it, one of many, and not by far the worst? The Bible insists that ‘hope maketh not ashamed’. But why should hope be associated with shame in the first place, so as to require rebuttal? Is it because despair is safer, more hard-headed, its bleakness more likely to be borne out by the world? Is there shame, then, in being wrong about the future? Or is hope a kind of false promise, an infectious one, and there is shame in leading others on, regardless of one’s sincerity and good intentions?

‘It takes schooled hope’, Ernst Bloch wrote, but how does one learn hope?

I close my eyes, take a deep breath, banish the questions from my mind and focus on the most serene of thoughts I can conjure, helped no doubt by my low energy levels. Faces of loved ones, near and far, stream through my mind. My boys, Ann, my siblings, my friends in my new Australian home, my nieces and nephews born in Lebanon and spread around the world – uprooted yet prospering – and, not least, my Levantine friends, from Aleppo in the North to Ramallah in the South, from Baghdad in the East to Beirut’s battered yet unbowed headland in the West: those who have stayed, and those who have left carrying with them small pieces of all-the-good-things-we-once-were, and spreading them in the world like charms or seeds, or just hanging them on the walls of their lives like good-fortune amulets.

The closing two sentences of Albert Camus’s Le mythe de Sisyphe come back to me:

Is this what keeps us going, the day-to-day quests and the small joys of kith and kin, despite the big calamities bearing down on us? There is something insistent, even urgent, in Camus’ call – one must imagine – as if our lives depend on it.

Hope emerges in me like the peeling away of doubt, a one-sided cessation of hostilities, a rising-above rather than a surrender, a form of faith in something visceral but whose substance I cannot quite pinpoint. A kind of happy resigna-tion – more stoicism of the aged perhaps, than optimism of the will.

There is hope in this shrug of an expression – ma hada b’yarif – a back-and-forth movement that releases the speaker from the immiserating urge to predict and shape one’s destiny, loosening a little the future’s grip on the present, while giving a grateful nod to the open-endedness of both.

I find a trace of hope too in that agnostic freethinker, and most pessimistic of Arab poets, Abu’l Alaa’l Maarri, author of Risaalat al-Ghufran – The Epistles of Forgiveness – who once lived not far from here. This is the man whose bust ISIS men saw fit to decapitate when they overran his native town of Maarra in Syria in 2013, almost a thousand years after his death.

Two verses of his now come back to me, like an incantation from a barely conceivable depth of time:

Two verses of his now come back to me, like an incantation from a barely conceivable depth of time:

The Nights pass so,

Voices dumb,

Without sense quick or slow

Of what shall come