On Friday, December 8, on the lands of the Burramattagal people of the Dharug nation, we launched our fourth anthology, Critic Swallows Book, and celebrated the first ten years of the Sydney Review of Books. The night saw a crowd of over sixty guests, comprising contributors, colleagues from Western Sydney University, and friends of the journal from the local literary community. We gathered to hear readings from Jeanine Leane, James Ley, and the recently appointed Parramatta Laureate in Literature, Yumna Kassab. The evening was MC-ed with characteristic panache by Augusta Supple, while the anthology was launched by SRB Editor, James Jiang. The night would not have been possible without the support and organisational nous of event organisers Iman Etri and Melinda Jewell (who also acted as photographer), Giramondo Publishing, Kate Fagan, Ben Etherington, Catriona Menzies-Pike, Chartwells Catering, and all our guests.

Augusta Supple, our MC for the evening

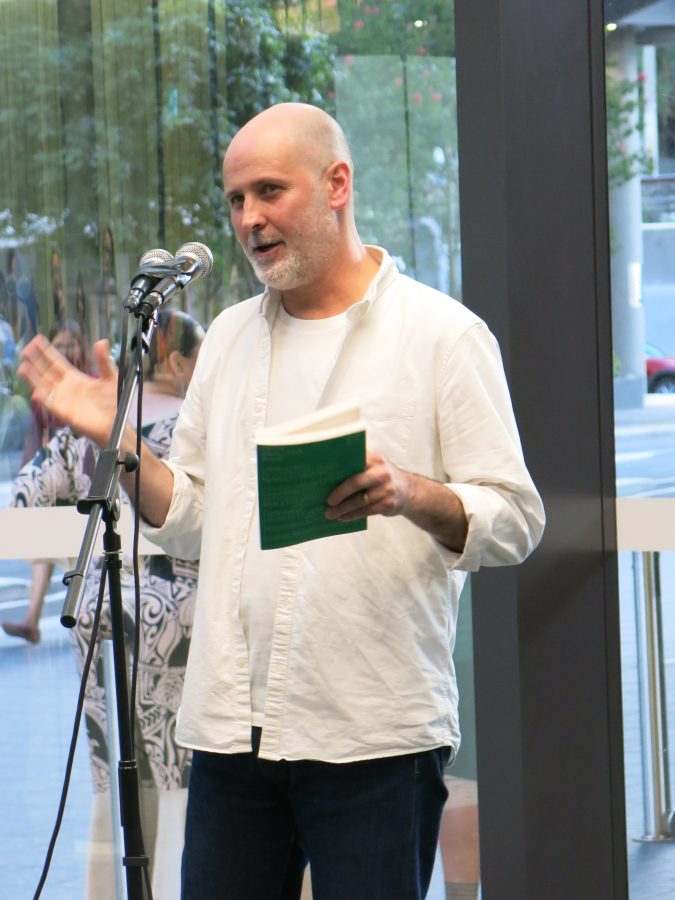

The following is an excerpt from the launch speech by James Jiang.

Launching a book is hard enough, launching an anthology even harder given the riotous mix of people and contributions involved. I feel like a bride who, instead of having a single bouquet, has twenty-two to toss into the air—an admittedly arbitrary image, save for the fact that an anthology is, at least etymologically speaking, a collection of flowers.

To publish a collection of critical essays is more of a unique occurrence than perhaps should be the case. The genre of the critical essay still fits oddly within a publishing landscape where it is usually annexed to that wonderfully amorphous grab-bag category of ‘non-fiction’—nor is it so easily embraced by the narrative-driven framework of ‘storytelling’ that has vastly expanded more Eurocentric understandings of cultural production. Criticism’s usual supports are to be found either in the institutions of journalism or those of the academy, even as its most adept practitioners (many of whom are included in this volume) evince a healthy skepticism about the practices and conventions in both these domains. It is worth noting that, in a literary calendar overcrowded with prize announcements, there is only one major award dedicated to critical writing in Australia—the Pascall Prize for Arts Criticism (which SRB contributors and both of its former editors have either won or been in serious contention for since the journal started)—and it is a prize funded by a journalistic organisation. To be clear: I’m not trying to say there should be yet more prizes, merely that the distribution of prizes across genre says something about public consciousness of, if not esteem for, criticism as a distinct artform …

In many ways then, Critic Swallows Book is a unique production, and it can be hard to know where to begin with a book that captures so many inflections of the critical voice in Australian literature. Taking their cue from Catriona’s eponymous contribution, the essays in this volume pull no punches—though they also pose the question about whether the pugilistic metaphor of punching is the best way to characterise criticism in the first place. In a scrupulous if unflinching performance, Oliver Reeson writes, ‘what I want criticism to do is not to promote or denigrate a work but really just to run alongside it, offering something else to think about, which you, the reader of this essay, can take up or refuse’.

James Jiang, Editor of SRB

Criticism, in this mode, is not an agonistic activity, not a matter of punching up or down (metaphors which tend to reduce the critical act of attention to a jockeying for social position); it is laterally rather than vertically oriented. It becomes a form of athletic companionability, in which the critic is as liable to be exercised by something that has otherwise have gone unnoticed as they are to come off as exercising (in the derogatory sense) for what may seem like petty exactitudes. Critics present as equivocal figures, and are often portrayed, as James Ley notes in his contribution, as ‘interlopers or disturbers of a supposedly natural cultural order’. In fact, when I came across Suneeta Peres da Costa’s characteristically lapidary statement that ‘We forget our own illegitimacy’, I’m tempted to take her to be referring as much to the critic’s ‘unhouséd free condition’ as to the callous convenience afforded by settler obliviousness.

James Ley reads from his essay, ‘Expert Textpert’

One way to dissolve ‘a supposedly natural cultural order’ is, of course, to turn to history. The critical imagination activated in these essays reckons with a dizzying array of time scales and temporalities, from the deep time of First Nations history to the more recent exigencies of the Anthropocene, from the millennial memory bank of Western philology to the multilingual archive left by South Asian travellers to Australia in the last century. While the main purpose of the anthology is not to chronicle the vicissitudes of Australian life over the past decade, the pressure of contemporary circumstance can be felt throughout the collection. Among the contexts shaping these critical reflections are: the 2016 Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory in response to the horrific treatment of Indigenous teenagers at Don Dale Correctional Facility, the catastrophic 2019-2020 bushfires that tore through over 24 million hectares of land, the murders of Eric Garner in 2014 and David Dungay Jr. in 2015 that galvanised the Black Lives Matter movement, and, of course, Covid. There’s plenty to celebrate in this collection, but also plenty that should give us pause. The costs of settler-colonialism, ecocide, and systemic racism are still accruing, in Australia as elsewhere. A lot has happened this past decade—and a lot continues to happen.

A collection such as Critic Swallows Book serves as a useful reminder, then, of both the literary events that have marked this past decade and literature’s entanglement in a broader social context. But criticism is more than just an aide-mémoire. It not only casts a spotlight on this entanglement, but through its acts of attention also brings this entanglement into being. Criticism becomes one way in which, as Andrew Brooks puts it, ‘sociality […] animates art’. Alongside the demystifications and debunkings—the attempts to cauterise a culture against its complacencies—in this collection, what stand out for me are those moments of elective affinity, testifying to Yumna Kassab’s astute assertion that ‘every person […] is best understood by what they love’. For instance, it’s hard not to be struck by the tenderness of Jeanine Leane’s observation that Evelyn Araluen’s brackets ‘evoke the visual image of hands that cradle intimate details of the poet’s identity that they can either choose to share or withhold’; or Bonnie Cassidy’s disarming recognition that ‘restlessness and pain, those itchy signs of life’ are precisely what we mean when we describe poems as ‘meditative’. These minute corrections of vision and expression amount to a not insignificant practice of care.

Yumna Kassab reads from her essay, ‘Vanishing Bolaño’

The therapeutic culture we’ve come to inhabit has turned ‘care’ and ‘community’ into the guiding principles of much artistic labour. Given what has transpired over the past twelve months (not to say the past ten years), a commitment to the reparative potential of artswork is laudable, if not necessary. But how do we prevent these terms from hardening into yet another set of neoliberal HR clichés?

Perhaps it’s better to start at the other end and reconceive what we imagine to be encompassed by the term ‘criticism’. Those of you who are faithful readers of the SRB newsletter will have heard me say before that ‘criticism is not a guild practice, the sole preserve of professional book reviewers’. And that ‘as important as the reviews and essays themselves are the conversations they provoke’ (at this point, I may as well have these words tattooed on my back). But what do these sentiments mean in practice? One thing they could mean is that we take a celebration like tonight’s seriously as a critical event, an opportunity for fortuitous and glancing conversation with a consequentiality we ought not to discount for its casualness.

Jeanine Leane reads from her essay, ‘Staring Back’

There’s an inspiring enactment of this in Melinda Harvey’s essay in this volume, a scandalously faithful pastiche of the narrative sleights-of-hand in Rachel Cusk’s style of autofiction. Chief among these, for Harvey, is Cusk’s handling of conversation through indirect speech. In the essay’s first vignette, three women gather at a restaurant, two of them having recently seen Cusk’s adaptation of Medea, to discuss the writer’s merits. Harvey has one of the women, Angela:

explain that Cusk had fumigated any residual inclination to be judgy by removing much of the thinking and feeling that comes with real life talk. Conversations have anteriority and posteriority: we anticipate them beforehand and we reflect upon them afterwards.

It’s worth insisting that the ‘thinking and feeling that comes with real life talk’ is the interpersonal medium from which these essays spring and in which they will live out their lives, both in this book and online. They are crystallisations of moments within this longer conversational arc, part of the anteriority and posteriority of discussions that happen unpredictably and on the fly—in restaurants, at literary events, on the plane. It is in this sense that we might consider criticism, unsentimentally, as a performance of community.