What matters is not what tribe or place the person was born to but what community the writer has made for themselves through reading, thinking, writing.

Coming of Age in Cabramatta

Sheila Ngoc Pham on Vivian Pham

The year is 1998. For those of us Việt Kiều who entered adulthood in the late ‘90s, our coming-of-age coincides with the coming-of-age of our entire community, growing as it did in foreign soil. This is the world recreated in Vivian Pham’s The Coconut Children.

From 'Cabramatta' by Matt Huynh, originally published in The Believer (2019). Reproduced with permission.

Over the years I’ve amassed many books by writers from Vietnam as well as the Việt Kiều diaspora – but I can’t claim these tomes spark joy. I can’t bear to get rid of them yet can’t bear the thought of reading most of them either. The Boat by Nam Le, for example, is one such albatross. When it was first published, and in the years after, I was often asked if I’d read it. My ready response was usually along the lines of no, but I own a copy. Whenever I’ve contemplated cracking the book open I recall it includes a short story called ‘Love and Honour and Pity and Pride and Compassion and Sacrifice’, which sounds far too much like a word association exercise in intergenerational trauma.

There are, however, a few notable exceptions.

In recent years I’ve read Anguli Ma by Chi Vu, Night Sky with Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong and just about every graphic memoir by a Việt Kiều creator. I was able to approach those books because of how spare they are with language; the oblique ways they confront what it means to be part of the diaspora. Some months ago I added the slim volume On David Malouf by Nam Le to my collection. This time I actually read it – and found it edifying as a fellow writer with roots in Vietnam who has thrived elsewhere. Here Le underscores the importance of artistic sovereignty over questions of identity:

Even so, I feel I owe something to this particularly burdensome part of my library, a stand-in for the dispersed community I’m a part of. My hoarding tendencies are undoubtedly related to refugee and migrant trauma; but Umberto Eco’s concept of the ‘antilibrary’ resonates as well. Here’s how Nassim Nicholas Taleb explains it:

Read books are far less valuable than unread ones. The library should contain as much of what you do not know as your financial means…allows you to put there. You will accumulate more knowledge and more books as you grow older, and the growing number of unread books on the shelves will look at your menacingly. Indeed, the more you know, the larger the rows of unread books.

So a significant part of my personal library is exactly this: a menacing antilibrary. These unread books are a daily reminder of how much I will never know about what it means to be Vietnamese, one of the great rhetorical questions of my life.

Given the current debates about representation in literature, I find myself reflecting on how I have always preferred books to be windows rather than mirrors. I was a voracious reader from a young age but growing up I didn’t particularly yearn for stories about what it meant to be Vietnamese – especially in Australia – because I was already drowning in the experience of it. In truth, I was far more interested in stories about unsupervised minors going on adventures, successfully solving crimes. In small towns where there were clear class structures were even better. Reading was more often a search for companionship and possibilities, not necessarily for validation of my identity.

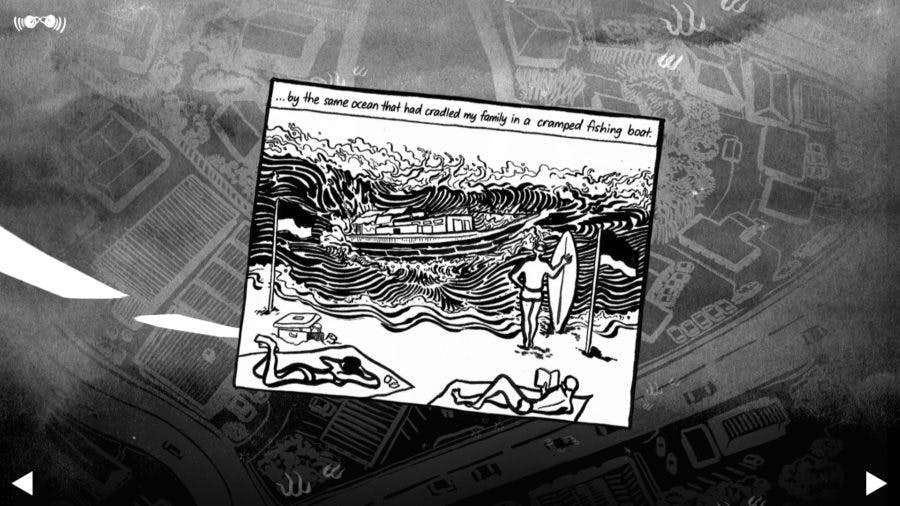

The first book I ever attempted to write was a Choose Your Own Adventure. Perhaps the structure of those books offered me a sense of freedom to move through worlds, even if only imaginary ones. But given the burden I carried about my family’s past, including the all-eclipsing boat journey, the thought of scribbling any of it into a rollicking adventure story was far from mind. (Thinking about it now, the idea of reducing the enormity of a refugee’s journey into a sequence of hypothetical choices still seems a bit ludicrous.)

So whenever I have specifically sought out and enjoyed refractions of myself in books, the reflection was always sidelong rather than full-frontal. Eventually, however, I understood that what I had directly experienced growing up in multicultural south-west Sydney during the ‘80s and ‘90s was worth narrativising. Not necessarily the particular contours of my own life but the broader shape of the Vietnamese diaspora in Australia.

As Toni Morrison said, ‘if there's a book that you want to read, but it hasn't been written yet, then you must write it'. Given my ambivalence about wanting to read such a painful book, however, it’s no wonder I couldn’t write it despite several attempts. I desperately felt the need for this book to exist but if it wasn’t going to be me who took on the almighty task of writing it – then who? It was a failure of my own imagination that I didn’t foresee it would be someone who wasn’t even born during the time in question; that a young woman twenty years younger than me could write with such clarity about the past I had lived through, and see what I had struggled with for so long.

The year is 1998. For those of us Việt Kiều who entered adulthood in the late ‘90s, our coming-of-age coincides with the coming-of-age of our entire community, growing as it did in foreign soil. This is the world recreated in Vivian Pham’s The Coconut Children. It is an intensely evocative and familiar depiction of the Cabramatta from that time, which I can still recall clearly, and traces of which exist to this day.

As The Coconut Children opens, a sixteen-year-old boy is released from juvenile detention. Vincent Tran is re-embraced by the Vietnamese community – 'Cabramatta welcomed her son back with quiet rejoice’ – but not by his immediate family. As part of a generation of lost boys, he is cared for by his friends and neighbours, including Sonny Le, the girl next door.

Sixteen-year-old Sonny lives in an intergenerational household with her grandmother, parents and younger brother. Vincent’s family home comprises of his parents and a newborn who arrived while he was incarcerated. Sonny feels stifled in her protective home, with a volatile mother and loving but ultimately unknowable father (‘It’d been strange to be raised by a man like him, a man always just about to vanish’). For Vincent, ongoing domestic abuse by his father draws out his protective instincts towards his gentle mother and baby sister. (‘As long as there stood a wall between them, they allowed each other to carry on as though they were part of the same family.’)

The novel follows Sonny’s and Vincent’s burgeoning connections with the adult world around them as well as the development of their relationship, the course of which certainly does not run smooth.

…she was too busy imagining what Vince might’ve smelt like when plop! – two eggs splattered against the back of her head, coating her hair in a sheen of mucus.

Their lives are girded by everything that has come from the old country merging with the possibilities of growing up in Australia. The languages of the past and present fuse; Sonny recites Shakespeare in class and Vince sings Vietnamese ballads at karaoke. Their mother tongue is skilfully woven in and out of the narrative, and we learn it is an old language infused with Chinese and other colonial remnants.

The red shrine was painted with golden Chinese script. No-one in the family could read the characters, only assumed them to hold auspicious meanings. Sonny preferred to believe they spelled out pure nonsense, like ‘heaven closing down sale’ or ‘rising phoenix farts smelly fortunes.

At the start Vince is repelled by the English of Shakespeare, until he eventually understands – through Sonny’s guidance – that Caliban in The Tempest is a mirror he can hold up to his own life. As Sonny tells him:

English used to belong to people like Shakespeare. Now it belongs to people like us.

From 'Cabramatta' by Matt Huynh, originally published in The Believer (2019). Reproduced with permission.

The Coconut Children can be read as an allegorical novel. Sonny and Vincent represent the two pervasive narratives of a community on the brink of maturation in a pre-September 11 world. It was a vulnerable, emotional, even chaotic time for the Vietnamese in Australia; as we struggled with our growing pains, it wasn’t entirely certain that we would ever achieve the stability we desired – and perhaps legitimacy as well.

I was a bit of a Sonny but I knew plenty of Vincents, such as one boy who had a brief stint at my high school. I was a student in the ‘selective’ half, had passed a competitive test to gain entry; he was a student in the ‘community’ half, drawn from the local area. Given the academic segregation I might never have had anything to do with him except our fathers were friends from the old country.

These two men came from different religious, family and class backgrounds – my rule-abiding father was an orphan getting by on his academic abilities, whereas his rebellious father was from a wealthy Catholic family. The two men reconnected as resettled refugees in Australia, and eventually their children attended the same high school. But our paths diverged when the boy brought a knife to school and was expelled; and as for me, well I'm sitting here writing this essay about a story I didn’t know how to write myself.

There’s a memory I have from the ‘90s which seems so surreal now I might have dreamed it: a campaign launched by members of the Vietnamese community that argued it wasn’t fair to frame all of us for the actions of the few. The only evidence I saw of it was a fleeting clip on the nightly news, contemporaries of my parents holding up placards with something along the lines of don’t frame an entire race.

Sixteen-year-old me thought they had a point. It seemed unfair that I should be tarred by the same brush, of gang- and drug-related crime, when I was adhering to the idea of being a so-called ‘model minority’. My thinking has long since evolved in terms of understanding how racism works, and why I now appreciate the truth of Sonny and Vincent’s lives being so intertwined and impossible to disentangle: ‘solitary and yet side by side’.

From 'Cabramatta' by Matt Huynh, originally published in The Believer (2019). Reproduced with permission.

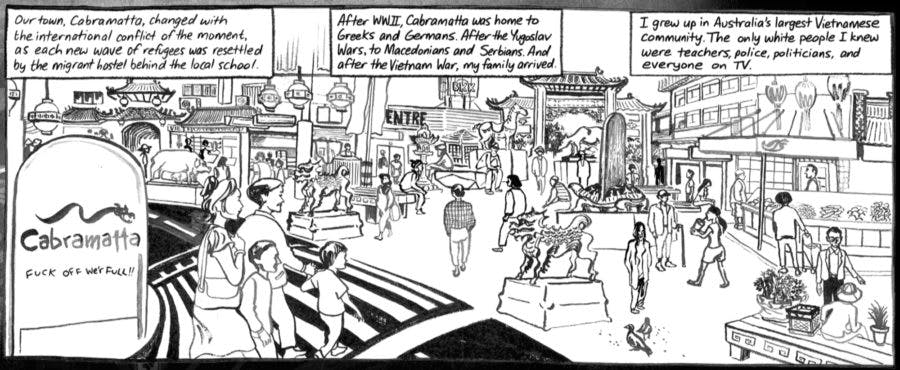

Cabramatta has long been a place that the media and, by extension, the community-at-large have liked to remark upon. But the tone of this commentary has fluctuated wildly over time. In the late ‘60s, for example, Gough and Margaret Whitlam moved their family of six from Cronulla to Cabramatta and used the opportunity to invite the excitable press into their new home. However, the suburb of Cabramatta would be transformed in a way that Whitlam did not foresee. In 1953 Whitlam had attacked French policies in Indo-China, arguing for Vietnamese self-determination; more than twenty years later this eventuated and lead to the extraordinary mass exodus from Vietnam.

During the ‘80s and ‘90s and well into the next decade, Cabramatta remained a subject of intense interest and scrutiny. The series Once upon a time in Cabramatta lays out the most prominent narrative of how the community transformed itself from being Australia’s notorious heroin capital to the more salubrious ‘A Taste of Asia’. A film such as The Finished People by Khoa Do is also worth recalling with its raw and moving portrayal of young homeless people who are ‘bụi đời’ (‘the dust of life’), existing in Cabramatta’s underbelly.

Another one of Cabramatta’s sons now based in Brooklyn, Matt Huynh, recently published an autobiographical comic about his hometown for The Believer titled Cabramatta. Panels from the comic illustrate this essay. It’s a compelling companion piece to The Coconut Children. Huynh’s comic is an immersive audio-visual rendering of the same period and his impressions and memories largely accord with my own. While Huynh was reading King Lear, however, I was reading Hamlet. This latest comic follows on from Huynh’s previous work CAB, a collection of short comics centred on Cabramatta.

Each of these attempts to capture the recent past – and these are by no means the only creative works out there – attest to the mythological quality of this particular time and place, the memory of which has dimmed in our collective conscious. Pham’s novel adds to the literature of Cabramatta with an even more mythical version, drawing together strands of stories she has heard rather than experienced. Through this historical fiction, she has reimagined what was and might still be.

When he would think about Cabramatta from inside his cell, it was always lit by the that ceremonial light of summertime… It was the same sun as anywhere else, but Cabramatta transported him – not to another country, but a crippled, blind and delirious soldier’s memory of it. So much of it, to him, was untranslatable.

There’s an earlier version of The Coconut Children published in-house by the Story Factory which was launched in December 2017. I probably wouldn’t have read it as per my usual practice had I not been urged to by my former Story Factory colleagues Richard Short and Bilal Hafda. The way they insisted made me think no, but I own a copy would not suffice. Perhaps knowing that the author was still in high school made it less intimidating.

In Stephanie Wood’s glossy Good Weekend profile about Vivian Pham and her family, she writes: ‘Vivian’s words soon found their way into the hands of Sydney literary agent Benython Oldfield’. In fact, after I tore through Pham’s book, I got into my car and drove from Wolli Creek to Oldfield’s office to hand him my copy.

The version of the book launched this year and published by Vintage Books has been considerably revised. When I read it in preparation for my interview with Pham at the Sydney Writers’ Festival, and in order to write this essay, I didn’t feel the same way about the revised version. There’s considerably less of the father’s refugee story and there’s a lighter touch throughout. It’s more poetic though, revelling in its own linguistic possibilities. But as a result the revised version feels more distant, a bit over-polished compared to the first. Perhaps I was too close to the first version, so it was hard to ignore the significant changes. I wanted to understand what occurred during the rewriting process; this is how she described it when we spoke for the festival:

I felt a huge sense of relief once that [first] version of the book had been published. But then in the two years afterwards when I was drafting it again with an editor I felt so much freedom to fictionalise it further. Putting it in this narrative already blurs the line between what happened and what’s made up, but I felt like I had more poetic license to experiment with it more and put more of my perspective as the child of someone who’s been through something traumatic. And not feel like I have to preserve it in its original condition and freeze it in time.

So in the revised version, Pham trades some of the intimacy of the first for much bolder and vivid prose. Compare a passage from the two versions:

How could somebody grieve, with an honesty that seemed to bleed, a love that was never his, a country that he’d never known, a memory he could never remember. Why had his history always felt so fucking mythical? Vince felt an absurd and meaningless pain. It was like digging a grave and having nothing to bury. He couldn’t even cry. (2020)

How could somebody lament, with such tender honesty, a girl who was never his, a country that he’d never known… they all felt a sharp pain, an inclination to mourn the loss of something which had never belonged to them. It brought Vince near to tears. (2017)

While reading the novel I did clock various minor anachronistic details, which I was surprised were overlooked during the editorial process. For anyone born after the internet, and with global capitalism firmly lodged in our way of life, I suppose it’s practically impossible to imagine just how slowly pop culture once travelled, and how far away the rest of the world felt. For example, Sonny and her best friend Najma discuss how they ‘had [n]ever stepped foot into a Victoria’s Secret store’ to try the brand’s perfume. But such a thought would have hardly been possible. We’d heard of Victoria’s Secret but the first store in Australia wouldn’t open for another twenty years; and if such stores existed in the United States the overwhelming majority of us wouldn’t even know, relying as we did on the media to selectively reveal the world to us. In 1998 teenage girls in south-west Sydney were most likely diffusing cheap Impulse, cK One and Davidoff Coolwater. We would have been unable to cite Wikipedia-detail understanding of perfumes as Sonny does:

Damask rose. Moss. Lavender. Frankincense. Resin. On several occasions, she and Najma had used the word ‘ambergris’ to convey the slow viscosity of honey scented with orange blossom, without knowing it referred to the excrement of a sperm whale.

The understanding Najma has about perfumes comes from her mother’s books by Abu Ali al-Hussein Ibn Abdullah Ibn Sina. He is described as a ‘Persian polymath’ who writes about the alchemy of distillation.

The Arabic words lulled her into the sleep of Hellenic ruins. An hour or two later, when she woke up surrounded by the ancients, Najma tried to return Ibn Sina to his alphabetical place but ended up knocking over The Metaphysics of The Healing.

It’s a beguiling vision of how knowledgeable and cosmopolitan the children of emigrés can be, but my recollection doesn’t entirely line up with Pham’s 1998 teenagers, who seem far more sophisticated than I remember any of us being. But I enjoyed their wit and precocity, no doubt a reflection of the novelist herself.

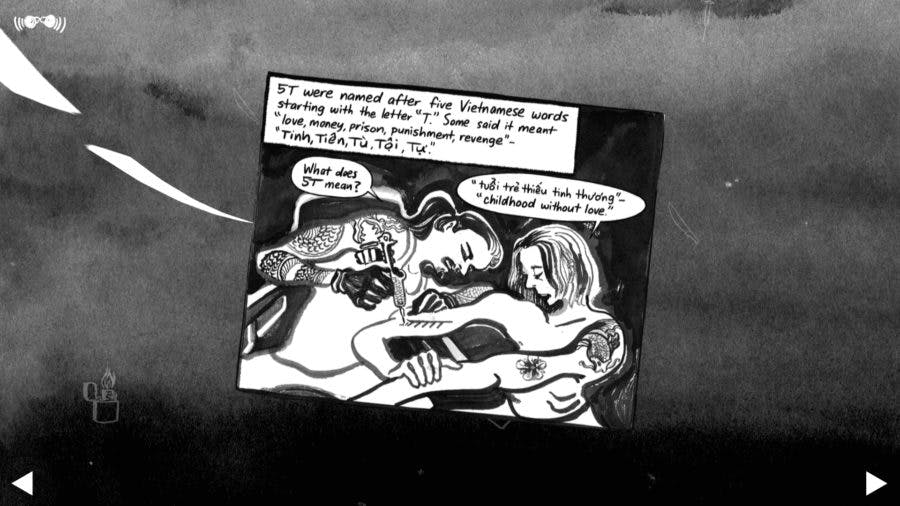

If I think back to the Cabramatta of the time I recall far more profanities and casual references to the 5T, bleached and home-dyed hair hanging over people’s eyes, the popularity of R’n’B and hip-hop. That’s more what it was actually like in 1998 – but then I remind myself that The Coconut Children is a fiction, sentimental impressionism rather than uncompromising realism. Which is exactly why it is such an ambitious book.

From 'Cabramatta' by Matt Huynh, originally published in The Believer (2019). Reproduced with permission.

The epigraph at the start of The Coconut Children is a powerful line from James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room: ‘I simply wondered about the dead because their days had ended and I did not know how I would get through mine.’ When I asked her why she chose this to frame the story, Pham told me:

Your connection to history can feel so strange and intangible, and I feel like that’s the pain of growing up as the children of migrants, and of refugees, is that you understand that there are people who came before you that sacrificed a lot for you to get to where you are. And you understand you come from a great history; but you wish there was more of a personal connection to those people who came before you.

She explained with such clarity what I implicitly understood, but had never been able to articulate as to why there is so much which remains unknowable. The Coconut Children is novel that will resonate with many of us who grew here in Australia. It’s a deeply spiritual contribution to the ongoing conversation between the past and the present, the dead and the living.