An anonymous letter arrives at the pharmacy of an unnamed Sicilian town. The postman doesn’t like the look of it. Nor does the pharmacist Dr Manno. Before opening the neat white envelope he spins through a range of emotions: unease, embarrassment, surprise, indignation, and finally a kind of quiet dread. His eyes flicker with trepidation. Beads of sweat burst on his upper lip. ‘This was a good man, a feeling, generous man,’ the postman reflects. In the world of Sicilian author Leonardo Sciascia, which is governed by a malevolent criminal bureaucracy more sensed than seen and known universally as the Mafia, these qualities of ordinary dignity set the pharmacist apart.

‘This letter is your death sentence,’ reads the text inside, pieced together from newsprint. ‘To avenge what you have done, you will die.’ Is it a sick joke? The townsfolk think so; Dr Manno too. Within a week, he sets out on a game hunt with his friend Roscio, the local GP. Both men are gunned down. Their dogs, with the exception of one who has been dispatched by the assassins, return to the town in a tight pack howling in lamentation. The local police are cynically, soporifically indifferent, and so the investigation defaults to the town’s Italian literature and history teacher, Professor Laurana, and as he slowly, falteringly, unlocks the mystery he seals his own fate.

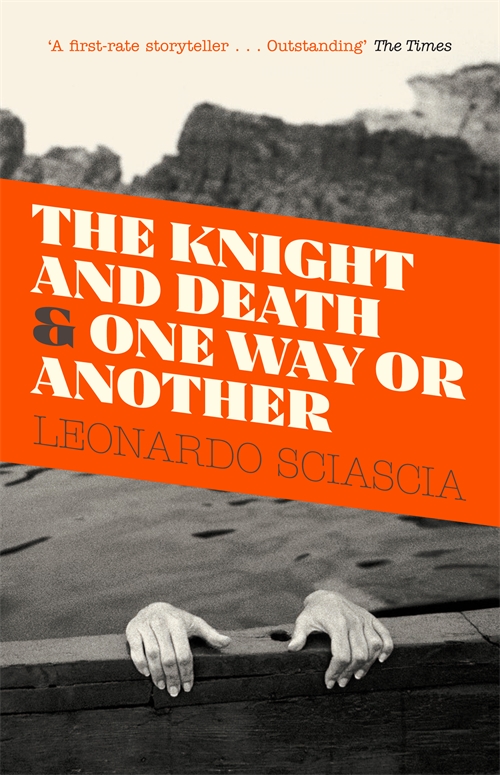

To Each His Own (1966) was the second of Sciascia’s novels, after The Day of the Owl (1961), to work the seam of highbrow crime for which he is best remembered. 25 years after his death, Granta has reissued most of his translated titles. These short, acrid tales are written in a dry Stendhalian style. Braided around their assured plotlines are philosophical dialogues on morality and politics, justice and mortality: universal themes with a distinctive Sicilian inflexion. These set pieces move from the particular to the abstract – the mystical and metaphysical – and it requires some effort on the reader’s part to wrestle them to earth. When Laurana visits Roscio’s father, a famous Palmertian eye surgeon, he finds him listening to a recitation of Canto XXX of Dante’s Inferno: an episode that broods on the sins of falseness, deceit, and forgery. The conversation begins with specific features of the case: Laurana has begun to suspect that Manno was the sham victim and the bullet was really intended for Roscio. But the teacher is soon drawn into a conversation about Catholic morality, eroticism, and the Sicilian attitude to life and death, as reflected in a pungent local proverb: ‘The dead man is dead, let’s give a hand to the living.’

To everyone but a Sicilian this reads like an injunction to altruism, but a real Sicilian understands it as a call to revenge. ‘A dead man is a ridiculous spirit in purgatory, a little worm with human features writhing on a hot brick,’ says the old man like a true student of Dante. ‘But when the dead man is our own flesh and blood, then, of course, we must do everything to send the live man – the murderer, that is – to join him forthwith in hell-fire.’

The highbrow detective genre is the backbone of Sciascia’s oeuvre and around it his other literary, as well as journalistic and political, activities cohere. Every few years, it seems, he felt the need to offer his readers a blood sacrifice: Equal Danger (1971), his third detective tale, or giallo as the genre is known in Italy, tells of a principled police inspector in an unprincipled land, who is called to action when three judges are shot dead in rapid succession. His inquiries compel him, as did poor Laurana’s, to face down a shadowy and self-protecting syndicate that flourishes at the fertile intersection of commerce, politics and crime. In truth, Sciascia is more interested in the Mafia supra-world – the socially elevated sphere inhabited by crime bosses and their political cronies and apologists – than the characterful underworld figures dominating Sicilian-American Mafia iconography.

In One Way or Another (1974), he elaborates on this theme of the interlocking or ‘concatenation’ (as he once put it) of power by setting a murder mystery in a remote monastery where the princes of the church, politics and industry have gathered for ‘spiritual exercises’ in the company of five prostitutes. The Knight and Death (1988) reprises the mood and the narrative strategy at the heart of To Each His Own – the murder as a feint in a larger game – although the tale this time is set in the revolutionary anni di piombo (or ‘years of lead’). There is a palimpsest-like quality in the relationship between these two tales written more than twenty years apart. The Knight and Death is propelled by a Stoical and ultimately doomed deputy investigator, who is dying of cancer, and is threaded through with meditations on sex, mortality and Sicilianism. The canine response to death is also recalled:

A thought which had never previously occurred to him now suddenly flashed into his mind: not one of them [the dogs of his youth] had died at home. None of them had been seen dying or found dead in their basket of straw and old blankets. At a certain stage in life, or at a certain stage in the progress of their bronchitis, it had been noted that they had no further taste for food or play, and they simply disappeared. As in Montaigne. And the fact, asserted almost as the Kantian imperative, as an illustration of that imperative, that one of mankind’s highest intelligences, in his wish that death should come to him, preferably in solitude but at least far away from those who had been close to him in life, had by meditation and reasoning attained what the dogs instinctively felt, seemed to him sublime.

A year after The Knight and Death’s publication Sciascia himself was dead from cancer.

Sciascia is read today chiefly for these so called ‘metaphysical crime’ novels; tales that were once thought to be conjectural, imaginary, spectral, but are now regarded as far-sighted, prophetic and even realistic anatomisations of a society in steady moral decline. In fact, his contributions to Italian political culture were manifold. Sciascia (pronounced shah-shah) was also a journalist, commentator and editor; a poet, dramatist and essayist; a sometime politician and a public investigator. He was also a writer of short stories and a luminous work of historical fiction, The Council of Egypt (1963), a chiaroscuro of bright surface detail and gathering shadow which is his most refined literary achievement. In his lifetime, he was a kind of Albert Camus with a defined geographical sphere. Or, to put it another way, if Camus had remained in Algeria he might have become another Sciascia.

In any event, the Sicilian writer was to become, and remains, an enduring feature of the national consciousness and, more particularly, its conscience. In Italy his novels have been filmed by directors such as Elio Petri, whose adaptation of One Way or Another, originally Todo Modo, eerily prophesied the kidnapping and assassination of Christian Democrat leader Aldo Moro in 1978. Italians were not surprised by the Mani Pulite, or Clean Hands, scandal of 1992 – which swept away much of the Italian political class in a system-wide corruption scandal. And the reason, in part, is that Sciascia’s nightmare political crime fictions had prepared them for it.

Already in Sciascia’s early works a dramatic imperative, or moral axiom, is laid bare. There is a type of dry-witted and inquisitive individualist whom he moves to the centre of his novels, and from whose point of view the narrative unfolds. The history teacher Professor Laurana in To Each His Own becomes, out of sheer dogged curiosity, a detective manqué. The plot unfolds at the pace of his stumbling investigations, propelled not so much by prosecutorial elan as chance and intuition. Inspector Rogas, the hero of Equal Danger, also carries the burden of his inquiries as if it were his own cross. So, with a slight variation of emphasis, does Inspector Bellodi, a northerner, in The Day of the Owl; he survives the machinations of the plot only to find himself recuperating in Parma, reflecting on Sicily’s ugly beauty and vowing to return, ‘Even if it’s the end of me’. The implication is that it surely will be. One of Sciascia’s abiding, and most unsettling themes, explored in these three works as well as The Council of Egypt where the reforming lawyer De Blasi suffers extraordinarily for his beliefs, is the tragic consequences for the virtuous of their virtue.

Sciascia likes to deprive his readers of one of the facile satisfactions of the detective genre: the triumph of good, even relative good, over bad. The genre dictates that every murder solved, every criminal bought to justice, represents a triumph of reason, a moral salve, a restoration of the social web. Crime fiction, in this sense, is essentially optimistic. In Sciascia’s hands, though, the genre is upended. His detective heroes are largely tragic figures. It is a Sciascian law that the closed ranks of the collective prevail over the isolated ‘good’ individual. The virtuous are exiles in their own land.

Born in 1921 in the ‘dead village’ of Ragalmuto, some fifteen kilometres north-east of Agrigento with its three ocean-facing Doric temples, Sciascia was schooled in Mussolini’s Italy. The Fascists managed to suppress an earlier, agrarian form of the Mafia, but the post-war years saw its revival and reorganisation. It migrated from the uplands to the cities, the coast and the ports, and from there to the New World and its cinematic celebration in The Godfather films of Francis Ford Coppola.

Sciascia lived through the anni di piombo, which climaxed in Aldo Moro’s assassination by the Red Brigades in 1978, quite possibly with the passive complicity of his own party. He subjects this political tragedy to a thorough excavation – relying often on the doomed politician’s letters from captivity – in The Moro Affair (1978), first published in the year of the tragedy that for many Italians has something of the flavour of the John F. Kennedy assassination (and which has spawned its share of conspiracy theories). In this book, and in another which it is often paired with, The Mystery of Majorana (1975), an examination of the wartime disappearance of Italian physicist Ettore Majorana, Sciascia reveals another side of his literary personality. Here he writes with a semiotician’s scrupulous attention to textual presences and absences. A Francophile all his adult life, Sciascia’s heroes were Enlightenment philosophers such as Voltaire and Diderot, but by this time he was clearly under the spell of Michel Foucault.

As an activist, a journalist and commentator – an engage intellectual – his sensitivity to the great social convulsions of the age allowed him to adapt the crime genre to the purposes of social critique. Out of the furnace of lived reality an anti-detective novel is forged: a novel in which the narrative is made to conform to a highly personal – and highly pessimistic – moral vision. No other Italian writer has penetrated as deeply into the ‘political mysteries’ of post-war Italy. Sciascia’s is a shadowed, lugubrious world, and a vastly different Sicily from the hedonistic meridional paradise of Andre Camilleri’s Inspector Montalbano novels with their gastronomic feasts, petty crime capers and seaside settings.

Though Sciascia vaunted his own ties to the French Enlightenment tradition it might be better to see his moral imagination as essentially Greek. He possessed the same quality of bitter lucidity as Homer or Sophocles. His inquiring, sleuthing heroes are either sacrificed to the powerful chthonic gods of Sicily, or else spurned. A light glows briefly, only to be engulfed by an obdurate darkness: the very opposite of enlightenment. This view of Sciascia as an essentially tragic novelist also resonates with the traditions of a culture whose deepest roots are Greek; Syracuse, with its magnificent theatre, was founded by colonists from Corinth.

Sciascia was also one of those writers, such as Dickens, Austen, Faulkner, Garcia Marquez and Joyce, whose literary imaginations are so deeply embossed with a specific milieu that their fictions become, in a sense, avatars of place. We go to their art to be diverted, certainly, but also in order that we might know an otherwise lost world. The old South is gone, or largely gone, but there will always be Faulkner’s South. As Edmund Wilson noted in his masterful appraisal of modernism, Axel’s Castle (1931), a propos of Joyce’s Ulysses (1922):

We see it only for twenty hours, yet we know its past as well as its present. We possess Dublin, seen, heard, smelt and felt, brooded over, imagined, remembered.

Sciascia, too, allows us to possess Sicily. Even his non-Sicilian novels – from the mid-1970s he preferred to give his tales vague fable-like settings – are psychologically Sicilian. As he put it:

All my books taken together form one: a Sicilian book which probes the present and develops as the history of the continuous defeat of reason and of those who have been personally overcome and annihilated in that defeat.

In the 1970s, Leonardo Sciascia gave a rare interview to the American writer Judith Harris, in which he explained that while he wintered in Paris to absorb the art, his novels were written freely over summers in Racalmuto, the products of concentrated utterance. ‘I never rewrite a word,’ he confessed. In life, he was a man of few words, a listener rather than a talker. But it would be wrong to couple this personal trait of innate taciturnity with the great cliché of the Mafia modus operandi – that it is an organisation of silences that thrives in a society of denial – and assume, as Harris does, that ‘the Sicilian author was about silences’.

Silence is an element of both atmosphere and plot, certainly. Without silence the crime novel would be deprived of mystery, shorn of dramatic tension. And yet Sciascia’s tales are as fiercely dialogue-driven as anything in Dostoevsky; they seem, at times, almost garrulous. This feature comes to the surface in the selection of short pieces published as The Wine-Dark Sea (1996), where tales such as ‘Philology’, ‘End-Game’ and the title story are in essence theatrical dialogues. Always, in Sciascia, there are voices. Even in the town square whose silence is about to be rent by ‘two ear-splitting shots’ from a lupara in The Day of the Owl, he gives us a fritter seller spruiking his humble wares, his voice ‘wheedling, ironic’.

Dialogue takes the form of a bombastic philosophical disquisition in Equal Danger, when Rogas interviews the President of the Supreme Court in an attempt to assess whether a ‘judicial error’ may have motivated the murder of several local judges. In the course of an exchange that extends over eleven pages, the president expounds a theory of judicial infallibility that springboards from a refutation of Voltaire’s famous ‘Jean Calas’ essay on religious tolerance.

‘The weak point in Voltaire’s tract,’ argues the president,

the point where I take off to set things right again, occurs on the very first page, when he proposes the difference between death in war and death at the hands, let us say, of justice. The difference does not exist; justice sits in a perennial state of danger, in a perennial state of war. It was also seen in Voltaire’s day, but it was not perceived, and in any event, Voltaire was too gross to realize it. But now it is perceived. What earlier could be gleaned by a subtle mind the masses have made microscopic; they have brought human existence to a total and absolute state of war. I’ll risk a paradox that can also be a prophecy: the only possible form of justice, of the administration of justice, could be, and will be, the form that in a military war is called decimation. One man answers for humanity. And humanity answers for the one man. No other way of administering justice is possible. I’ll go further: there never has been any other. But the moment is coming to give this fact theoretical expression, to codify it. To prosecute a guilty man, guilty men – is impossible – practically, technically impossible … War exists, and dishonor and crime must be restored to the corpus of the multitude the way in military wars it is restored to regiments, divisions, armies. Punished by lot. Tried by fate.

As a satire of jurisprudential casuistry this – and in fact the dilatory exchange in which it is embedded – sorely tests the reader’s patience, especially the reader who has come to the detective novel expecting some of the pleasures of the genre. The satisfactions Sciascia the moralist withholds are those of resolution and restitution. But Sciasica the writer offers many compensatory joys. Perhaps the most writerly of his novels is The Council of Egypt, set in Palermo in 1783, which narrates the story of an opportunistic abbot, Giuseppe Vella, who forges an Arabic chronicle that brings him instant fame and releases, in time, vicious political forces. The novel’s ending is as dark as anything in Sciascia’s body of work, yet the opening promises a rich palette of surface detail and a bright ornamental style. It is as if the author, released from the terrible weight of the present into an imagined past, was able to breathe more freely.

The Benedictine whisked a brush of multicoloured feathers over the top of the book, puffed out his plump cheeks like the god of the winds in an old nautical map, blew black dust from the leather cover, and, with a shiver of what in the circumstances seemed delicate trepidation, laid the volume open on the table. The light fell slantingly from a high window onto the yellowed page, so that the dim characters stood out like a grotesque army of crushed dry black ants. His Excellency Abdallah Mohammed ben-Olman leaned down to study them; his eyes, habitually languid, weary, incurious, were now sharp and alert. He straightened up after a moment, reached under his redingote with his right hand, and drew forth a magnifying glass; the frame and handle were of gold, with green stones so set that the glass seemed a cluster of flowers or fruit on a slender stem.

The passage is filled with Palmertian light and bejewelled with colour: with gold, green stones; multicoloured feathers, flowers and fruit; black dust and yellowed paper. Physical incident, precisely drawn, sets this painterly interior in motion. The writing is finessed with movement, by the use of simile and subtle variations of rhythm.

The literary influences that worked Sciasica were as various as the modes in which he worked. Poe, Shakespeare and G. K. Chesterton were his anglophone heroes. The word ‘adorable’, Sciasica once confessed, he reserved for certain women – and for Stendhal. The works of his narrative master with their evenness of emotional weight – their equability – were in constant rotation on his private reading list, the Charterhouse of Parma never far from his thoughts. Aside from the literary philosophers of the Enlightenment – Voltaire’s Candide held a special place in his affections – there were his Italian masters Vitaliano Brancati, author of the novel Don Giovanni in Sicily (1941), and another fellow Sicilian in Luigi Pirandello, whose humanism, hall of mirrors illusionism, and fondness for play and paradox leave their stamp on the novella One Way or Another. This hyper-literary existential murder mystery with a political sting reads like something Agatha Christie might have produced after ingesting a polyglot’s library. The work is bookended by a lengthy passage from Pseudo-Dionysius, and another from Andre Gide. Barely a word of dialogue is without irony. And yet when the narrator, an artist, relates his debt to Pirandello, one hears the authentic voice of Sciascia: ‘I was born and had lived for years in Pirandellian landscapes, among Pirandellian characters, with Pirandellian traumas …’

In the final years of his life, the writer who had done more than anyone to unveil the Mafia and expose the corruption of the entire political class (northern as well as southern), made a profound political faux pas. In January 1987, he slandered anti-mafia activists including Judge Giovanni Falcone as ‘anti-Mafia professionals’, the implication being that they were grandstanding judicial pop stars insensitive to the deep Mafia whose coded workings only Sciascia could discern. At the time, Falcone was completing a ‘maxi-trial’ of Sicilian crime figures, which led to the successful prosecution of 300 mafiosi. In March 1992, soon after launching another series of maxi trials, Falcone was killed in a massive blast of TNT planted by the Mafia. Shortly afterwards, his colleague Paolo Borsellino was assassinated. It was a pivotal moment. The Mafia had declared war on the state, and the state was compelled to act. The old school mafia, from that moment, has been in retreat on the island.

What was Sciascia thinking? His motivation remains a mystery. It does, however, make a perverse kind of sense when viewed in the light of the standard Sciasican fictional hero. The writer’s corrosive skepticism made it difficult for him to accept the integrity of an extroverted, high profile and glamorous mafia buster. His good men are earnest, introverted, isolated – and doomed. There was one trait in this catalogue that Falcone did share, though Sciasica, who died in 1989, was not to know it: the last.