It overturns and the red sauce and yellow pasta loosen their greasy grip and separate in clumps and ribbons through the water.

Oh babe, I didn’t mean to…’ Dean stops. I am ducked water level to eat my way through the mess, my mouth open and sucking, revolted and ravenous at once. Dean retches. I eat.

Living Through Allegory

Lauren Collee on Laura Jean McKay

By probing the interpretative challenges inherent in allegorical writing, Lauren Collee offers a different look at the award-winning speculative work of Laura Jean McKay.

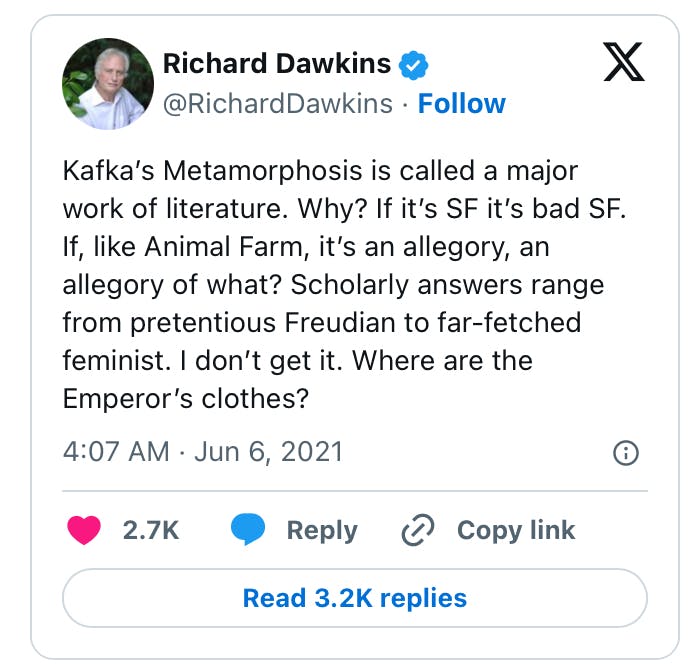

About a year into the pandemic, Richard Dawkins took to Twitter to loose his opinion of Kafka on the world. ‘Kafka’s Metamorphosis is called a major work of literature’, he wrote. ‘Why? If it’s SF it’s bad SF. If, like Animal Farm, it’s an allegory, an allegory of what?’

Predictably, and perhaps as Dawkins intended, the tweet attracted widespread ridicule. But while it may seem ludicrous to propose that Kafka’s short story be read as bad sci-fi, it’s not all that easy to say why. There is an affinity between sci-fi and allegory, both of which require the reader to hold their understanding of ‘reality’ alongside the story’s contrivances. Dawkins’ implication – that the only difference between the two was that allegory’s primary meaning lay ‘outside’ the text – raises the question not only of how to define both genres, but also why it matters. Does an allegory turn into sci-fi when there’s no agreed upon referent? Does sci-fi become allegory when its bearing on the ‘real world’ congeals into an established interpretation?

Dawkins’ strange tweet came back to me while I was reading Laura Jean McKay’s new collection, Gunflower. The recipient of a prestigious Arthur C. Clarke Award for science fiction (awarded to her 2021 novel, The Animals in That Country), McKay is often marketed as a leading exponent of the genre. ‘Science fiction’ might seem like the right label for many of the stories (some long, some as short as prose poems), in which cats are farmed for their fur, rocks can talk, and women gather in a world where all the men have mysteriously disappeared. But for reasons that I struggled at first to pinpoint, allegory seems a better fit for the collection as a whole, which is arranged into three sections – ‘Birth’, ‘Life’, and ‘Death’ – though it is not always clear what is dying, what is living, and what is being born.

‘Allegory’ is not an easy word to define, and efforts to do so often reflect much larger debates about the relationship between language, image, and truth. Around the turn of the nineteenth century, Goethe – and later, Coleridge – drew a distinction between allegory and the symbol, arguing that only the latter was worthy of serious literary consideration. Where the poetic symbol directly captured an inexpressible truth, they argued, allegory merely attempted to render truth comprehensible, and in doing so, bastardized it. Such was the dominant view of allegory in the West until around the 1920s, when Walter Benjamin began to question the dismissal of allegory on the grounds of its supposed falsity. To think allegorically, for Benjamin, was to recognize that figural expression was not opposed to ‘truth’, but fundamentally constitutive of it.

As the post-structuralists took up Benjamin’s ideas and developed them, allegory was increasingly embraced for the very reasons it had formerly been dismissed. As an openly ‘deceitful’ mode that was concerned with the deferral of meaning, allegory reflected the inherent instability of not only language, but of ‘reality’ itself. Among these ‘new Allegoricists’ (as the literary theorist Joel Black calls them) was Maureen Quilligan, who in The Language of Allegory (1979) argued that allegory was more than a mere attribute of certain texts, or an interpretive strategy – it was a distinct genre with its own set of literary conventions. For Quilligan, attuning ourselves to these expectations would reveal the function of allegory, which was to ‘manipulate’ the reader into the self-reflexive realisation that they were interpreters of both literature and the world around them.

True to this function, many of McKay’s stories consciously engage the readers’ expectations of what allegory looks like, and what it is supposed to do. Take, for example, ‘Flying Rods’, in which an adulterous woman is bitten by a mosquito and subsequently undergoes a transformation into a mosquito-like creature. There’s a nod here to the classical roots of allegory – Aesop’s fables, for example – in which animals stood in for the morality or immorality of distinct human qualities: a lion for bravery, a fox for stealth, a mosquito for adulterous lust. But like Metamorphosis, which is (at least in part) about a man turning into a bug, ‘Flying Rods’ is also genuinely interested in what it is like to be a creature trapped between human and animal worlds.

The reader of ‘Flying Rods’ is put to work, cross-referencing the story with ‘the real world’, including a few well-known facts about mosquitos: their vision is different; they like standing water. ‘Everything is dim’, notes the narrator, who won’t get out of the bath: ‘red, yellow, green, and purple – there are no other colours.’ In one scene, her partner, Dean, brings her a plate of spaghetti Bolognese:

Exploiting food’s liability to evoke disgust when seen out of context, McKay conjures up a messiness here that has to do with the ‘overturning’ of not only physical boundaries, but also conceptual ones. Within the species-limbo of the story, neither the narrator’s ‘sucking’ nor Dean’s ‘retching’ appears more appropriate than the other in response to the dislodged food. The dilemma of a body that is ‘revolted and ravenous at once’ isn’t the bodily dilemma of a creature trapped between different evolutionary lineages, but rather the linguistic dilemma of a creature trapped between competing frames of reference.

The tendency of illness to upend our sense of a clean line between inside and outside is a theme that surfaces frequently in McKay’s writing. In a 2021 interview about The Animals in That Country with Headland, McKay recounts an experience of contracting a virus called chikungunya from a mosquito in Bali: ‘I did get the sense – as I was deep in fever, skin peeling off, totally delirious with pain – that I was inside Franz Kafka’s novella Metamorphosis’. One could call this a literal interpretation of Kafka’s story; but in McKay’s work, as in Kafka’s, there is no real difference between the literal (in this case, bodily) and the allegorical (linguistic). The tragicomedy of Metamorphosis lies in the plight of the bug-man who not only has to live with his ‘condition’, but is also forced to reflect, in language, on the state of being a bug. Similarly, the feverish mischief of ‘Flying Rods’ lies in the articulation of animal desires that should never have had linguistic expression: ‘I can smell more blood, other blood, new blood. Out there. Un-tasted. Big blood and small. Blood in the trees and blood in the yards’.

A slightly different experiment takes place in ‘Those Last Days of Summer’, which is about a host of ‘sisters’ who are ‘always giving birth’ under the glow of an artificial and near-perpetual summer: ‘we starved that winter, some died, and then finally someone gave birth and set us all off again’. There are a few details that suggest the narrators are chickens – feathers, brittle legs, ‘arms made useless’, and a kind of chatter reminiscent of clucking (‘don’t go, don’t go; go, go, go, go’), but the language is deliberately species-ambiguous, sitting somewhere between the bird-like and the human. Which realm of experience is merely the allegorical vehicle, and which is the ‘real meaning’? Viewed from one end: animal suffering only comes into view when it is analogised with human experience. Viewed from the other: human suffering only becomes visible through its animalistic articulation. But neither interpretation works as the ‘real one’, because ‘Those Last Days’ is and isn’t about human reproductive labour, just as it is and isn’t about chickens. It unfolds precisely in the undecidable gulf between ‘chicken’ and ‘woman’, between ‘laying an egg’ and ‘giving birth’.

Why are animals so central to allegory? There’s a clue in John Berger’s concept of metaphor, which he claims emerged from man’s relationship with animals. ‘The parallelism of their similar/dissimilar lives allowed animals to provoke some of the first questions and offer answers’, he writes in an essay entitled ‘Why Look at Animals?’ (1980). ‘If the first metaphor was animal, it was because the essential relation between man and animal was metaphoric.’ The birth of metaphor was the birth of reflexivity, the faculty that supposedly distinguished humankind from other creatures. Paradoxically, though, this reflexivity was only made possible by the gaze of the animal, which held a ‘special message just for Man’. This ‘special message’, which remains unspecified, unfolds in the abyss between recognition and alienation, between similarity and difference.

For Coleridge, metaphors – which involve linguistic abstraction – were closer to the debased form of allegory than the pure or immediate form of symbolism. Animals are metaphors, but the process of turning them into metaphor is a conscious one, with the effect that they reveal more about us than the animal in view. In McKay’s ‘Nine Days’, a woman mourns the stillbirth of her daughter, Cara (‘Cara for darling, diamond, dear’). The story unfolds in loops of unfinished thoughts, taking on the stilted confusion of grief, as the daughter’s name is vaguely echoed in words that speak of death: ‘Cara, I have crept here’. A bird mangled by the narrator’s cat calls out the first syllable of the dead daughter’s name, a ‘muffled ca-ca-ca’, never getting out the last syllable before it dies in the kitchen (‘the body […] pasted to the floor with blood’). The voice stalls; words are born still. Allegory becomes a tool for survival as the narrator grieves the daughter through the more comprehensible death of the young bird: ‘That beak would never hunt the frogs or snakes. It was too awful. That she would never grow’.

The literary critic Northrop Frye famously said that the act of allegorizing was the work of all criticism and commentary. As Quilligan points out, though, while allegorical criticism is a useful tool for non-allegorical texts, it is paradoxically best not to study actual (generic) allegories using the tools of allegorical criticism. Instead of merely identifying its true ‘meaning’, the process of interpreting an allegory is supposed to ‘go on forever’. We are supposedto fall into the gulf between story and referent (between chicken and woman, between baby and bird). The ‘obsessive’, ‘self-reflexive’ and ‘critically-self conscious’ state this generates is the central characteristic of allegory as a genre. Quilligan writes: Comedy, romance, satire, tragedy, and epic are all categories that classify works essentially according to the human emotions they evoke. We laugh at comedy, wonder at romance, snort at satire, feel pity and terror at tragedy, and admire a hero after reading an epic. The works’ forms are designed to evoke these responses. After reading an allegory, however, we only realize what kind of readers we are, and what kind we must become in order to interpret our significance in the cosmos. Other genres appeal to readers as human beings; allegory appeals to readers as readers of a system of signs, but this may be only to say that allegory appeals to readers in terms of their most distinguishing human characteristic, as readers of, and therefore as creatures finally shaped by, their language.

Comedy, romance, satire, tragedy, and epic are all categories that classify works essentially according to the human emotions they evoke. We laugh at comedy, wonder at romance, snort at satire, feel pity and terror at tragedy, and admire a hero after reading an epic. The works’ forms are designed to evoke these responses. After reading an allegory, however, we only realize what kind of readers we are, and what kind we must become in order to interpret our significance in the cosmos. Other genres appeal to readers as human beings; allegory appeals to readers as readers of a system of signs, but this may be only to say that allegory appeals to readers in terms of their most distinguishing human characteristic, as readers of, and therefore as creatures finally shaped by, their language.

In other words, allegory foregrounds the reader as a linguistic animal, for whom the work of generating and interpreting signs is, as Quilligan argues, the very work of living. The notion that this is truly the ‘distinguishing human characteristic’ is a fact that Quilligan herself (with her reference to the human as ‘creature’) appears suspicious of. There’s a connection, as Jacques Derrida recognised, between the work of writing and reading, and that of tracking and leaving a trace. If animals can read (interpret the traces of others) and write (leave their own traces), then who is to say that animals can’t allegorise?

While The Animals in That Country was preoccupied with the notion of inter-species communication, Gunflower seems more interested in the question of what language even is in the first place. In ‘Come and See It All the Way from Town’, it’s not animals that talk, but rocks. The adolescent narrator and their teenage sibling misunderstand these voices. At first they think they’re coming from the dog, Jacko, who appears to be saying things like ‘what’ and ‘bloomin’’. The kids are corrected by their father: ‘Not what, but watt. Not bloomin’ but lumen. They’re after our light.’ The rocks used to speak in te reo (Māori), says the father; now they speak English, and struggle to make themselves understood. McKay points out that words might seem to be a way of fixing the natural world into place, but ultimately this fixity is an illusion. Behind each word is a shifting and complex negotiation of desire and expectation. What makes Jacko more likely to be heard by an English-speaker as saying ‘bloomin’, than a rock saying ‘lumen’? We can’t really be sure of the Father’s interpretation, or that he’s actually giving the rocks what they want by shining his spotlight onto the hillside each evening. We also don’t know exactly what’s at stake in this misinterpretation. Behind the rocks’ vocalisations is the shadow of a threat: ‘They reckon there’s light – electricity – coming from our bodies’, explains the father, ‘and they’re asking about it.’

Of all the stories in Gunflower, I liked ‘Come and See It All the Way from Town’ the best; partly because it reminded me of Kafka’s ‘The Rescue Will Begin in its Own Time’, a collection of four very short stories which can be thought of as allegories about allegory. In one of these, the myth of Prometheus is narrated in four distinct ‘legends’, over the course of which the punishment (having an eagle eat his liver anew each day into eternity) dissolves into meaninglessness. The story ends on the following line:

Everyone grew tired of the procedure, which had lost its raison d’etre. The gods grew tired, the eagles too. Even the wound grew tired and closed. The real riddle was the mountains.

The action of ‘interpreting’ allegories often rests on breaking it down into its constituent parts, and identifying the referent for each one (whom does Prometheus stand in ‘for’? who or what are the ‘eagles’ – or the ‘gods’?). At first encouraging a granular (almost investigative) reading of the myth, the story gradually shifts the story’s emphasis from the internal mechanics to the question of where the boundaries of a ‘story’ lie in both space and time. In a similar movement, McKay’s ‘Come and See it’ begins by asking the question of who is speaking (the dog? the rocks?), moves to asking what they are saying (bloomin’? lumen?) and ends by asking what it means to speak at all.

The theme of landscape is well suited to these kinds of self-reflexive actions because it is intimately bound up with philosophies of perception (backgrounds, foregrounds, emphasis, framing). In a sense, the ‘real riddle’ of Gunflower lies beyond the stories’ bounds in a landscape that is always receding. Many are set in coastal areas, borderlands, on the verandas of houses that seem just to hold out against what’s beyond them. These landscapes are lonely and barren; their pull on the characters is the pull of negative space. In ‘Nine Days’, the house is clouded with a ‘sweet steam’ that ‘drifts in from the unfilled swamp’. In ‘A Sensation of Whirling’, the house borders a ‘paddock thick with rabbits and crickets and cheat grass and not much else’. In ‘279’, the house stands amid flooded paddocks, and though the drowning cows call out through the rain, ‘there are no other sounds. Lowing and water’. In ‘Site’, a view of the ocean from a bedroom window becomes ‘a nothing sky fading into sea’.

One could read these as descriptions of literal emptiness; indeed, two of the collection’s stories are set explicitly in worlds where most other species have disappeared entirely. But this negative pull can also be read in light of the strange way that ‘landscapes’, especially in settler colonies, are figured as both substantial and insubstantial, animate and inanimate. Landscapes should be alive enough to be beautiful and profitable (brimming with flora and fauna), but not alive enough to be a threat (they shouldn’t flood, they shouldn’t burn, and they definitely shouldn’t talk). Caught eerily between being too animate and not animate enough, Gunflower’s (usually rural) landscapes elicit strange behaviour from the characters, who sometimes venture into the terrain beyond their homes for fun, but often seem haunted by an odd disconnect. In ‘Gunflower’, the crew of an abortion ship caught in a storm attempt to return to America only to find that the entire continent seems to have disappeared. In ‘Site’, conversely, it is the existence of the ship that is in question. Despite its flickering, translucent form, the ship is able to breach the coastline and plough through solid terrain. In the settler imaginary, land can seemingly be made to appear or disappear at will; rendered animate or inanimate according to settler needs. The consequence of this, though, is that land becomes something ghostly and unpredictable.

In very concrete ways, the worlds of Gunflower are shaped by the interdependent violences of colonialism, capitalism, and misogyny. But efforts to allegorize these forces explicitly don’t always work, perhaps because in theory for something to function as a referent, it can’t simultaneously appear within the story. This is particularly the case in the middle third of the book, in which the realist stories are the more engaging ones. Take, for example, ‘Real’, a very short and musical vignette in which two housemates seek refuge from the rain in a bus shelter, sharing hot chips while cracking jokes about ‘the most attractive real estate agent in the region’. The story crackles with innuendo (‘“You’ve got a good heat pump, Craig Henderson”’), behind which lies a much deeper conflagration of desire and anger: ‘But how much do you want, Craig Henderson? Your golden hands. Your reflective face. Our jackets stink of hot oil, but they’re warm’. Surrounded by reflective or repellent surfaces (faces, billboards) that speak of the exclusivity of the property market, the narrators find signifiers of homeliness in the concave structure of the bus shelter, the embrace of a jacket, the swallowing of a hot chip. There’s a trap here, though, which is the central trap of a system in which participation is not a choice: any act of defiance – such as locating the feeling of home outside of property ownership – can be equally figured as an act of resignation. The hot chip might take on the golden glow of the hearth light, but ultimately one can’t live inside a hot chip.

McKay’s orchestration of the ‘material’ properties of language – how words look and sound – is common to all of Gunflower’s more potent allegories. In ‘Lighting Man’, the wife of an auditioning circus lighting operator attends his trial show, accompanied by a wealthier girl whose relation to the family is unclear. In the carnivalesque atmosphere of the circus tent, wealth and poverty are rendered in a series of prosodic and visual textures. The narrator observes her children salvaging a dropped lolly, reflecting on ‘the lengths they’ll go to lick or pick the scum off a thing so that their first taste is a good one’. She adds: ‘I don’t mind that they run and scrounge around. I don’t begrudge them a lick of their lolly so long as they all get some’. There is a kind of scabby nursery-rhyme musicality to the prose here, the shorter vowels rendering an easy shrewdness (‘lick’, ‘pick’) even as the longer vowels conjure the muddy inertia of daily effort (‘scrounge around’). As she waits for the signal that her husband, the ‘Lighting Man’, has succeeded in securing the job that will lift them out of the dirt, her eye catches on other bright things: ‘froth and laces’, the girl’s bright teeth, her blonde curls. For a family used to ‘scrounging’, even the circus ring, in which the gift of spectacle is all but guaranteed, becomes the site of a desperate gleaning: the spotlight, when it finally comes, is like a ‘penny or pearl in the street’.

‘Territory’, a story in which two men and a woman go boar hunting, has a careful linguistic palette made up of death, sex and meat. Within the story, even an innocuous seeming word like ‘buggy’, which literally describes their mode of transport, has echoes in the flies (bugs) that jump from pig to man, in the word ‘pigging’, and in the specter of ‘buggery’ that haunts both these words as a homonym. There’s no difference, here, between the ‘truth’ of the senses and the mediations of language. If man is a creature shaped by language, then language, equally, is a phenomenon shaped by man’s creatureliness.

While reading Gunflower, I had strange, vivid dreams. In one, I tried to convince my parents that the tiger visibly pacing outside the door was a threat to the family dog they wanted to take for a walk. In another, an enormous, gnome-like creature sat in the corner of the basketball court, ignored by the students and teachers playing there. In yet another, I peered into a space between the rafters to find a family of owl-human hybrids; but when I tried to show someone else, the owl-people were gone, and nobody believed what I’d seen. In a sense, all of my dreams revolved around the feeling of witnessing a presence that I could not make ‘fit’ with the human logic of a scenario.

For Berger, the origin of metaphor lay in the act of literally looking into an animal’s eyes, and feeling an experience of similarity and difference that was akin to the gulf between a sign and its referent. Like metaphor, allegory is underpinned by an uncanny affective encounter with the non-human. I wonder what Berger would make of the fact that many of the allegorical texts reaching the widest audiences now – Barbie, for example, or The Little Mermaid – seem to be those that dramatize an encounter between the human and its eerie counterpart? (Barbies and mermaids are like people, but not people; they invite comparison, and frustrate transposition.) Arguably, the mistake these films make is to grant their audience the spectacle of a perfect union of human and non-human worlds. In doing so, they close down more questions about how we define the ‘human’ than they open up.

At its most efficacious, allegory functions through deferral and dispersal rather than completion and synthesis. As in a dream, its truth is always just out of arm’s reach. This makes it a genre well suited to the so-called Anthropocene, in which the ‘true meaning’ of every action – buying a coffee, throwing away the cup – is always deferred, always endlessly multiplied on scales far beyond the most immediate frame of reference. ‘Allegory is a genre for the fallen world’, Quilligan points out, referring to John Milton’s reflections on language’s sinful devolution into an elaborate system of deception, ‘but it is a genre self-conscious of its own fallenness’. For McKay, as for Berger, there will be no perfect moment of mutual comprehension between human and non-human worlds; the ‘secret message’ that the animal holds for man will never be truly disclosed. The gulf yawns, it breathes its secrets into the air, it refuses to be stitched up.