all diverse experiences, including (but not limited to) LGBTQIA, people of colour, gender diversity, people with disabilities, and ethnic, cultural, and religious minorities

The Power of Seeing Yourself on the Page

Jeanine Leane on Gary Lonesborough

Right from its opening line: ‘The white boys stare at us from the pub’, this story brings its readers into the First Nations community of south coast of NSW and into the realm of Aboriginal protagonist Jackson on the cusp of adulthood.

Palyku law academic and author Ambelin Kwaymullina recently called for informed cultural commentary on literature written and marketed for youth in Australia today. Writing for The Conversation Kwaymullina defines diversity in this way:

Kwaymullina goes on to note that while there are many differences between diverse cultural identities there are also points of intersection. One of these intersecting points is the extent to which mainstream young adult literature is failing our youth. This chronic lack of diversity not only influences how diverse peoples see themselves, but it influences how they are seen (and in many cases not seen) by those of the dominant culture. The situation is accentuated by the fact there is often a long history of misrepresentation of diverse identities in narratives written about the other. In relation to Australian Indigenous peoples First Nations Bunjalung writer Melissa Lucashenko calls this ‘the great poisoned well of historic writing of Aboriginal people’.

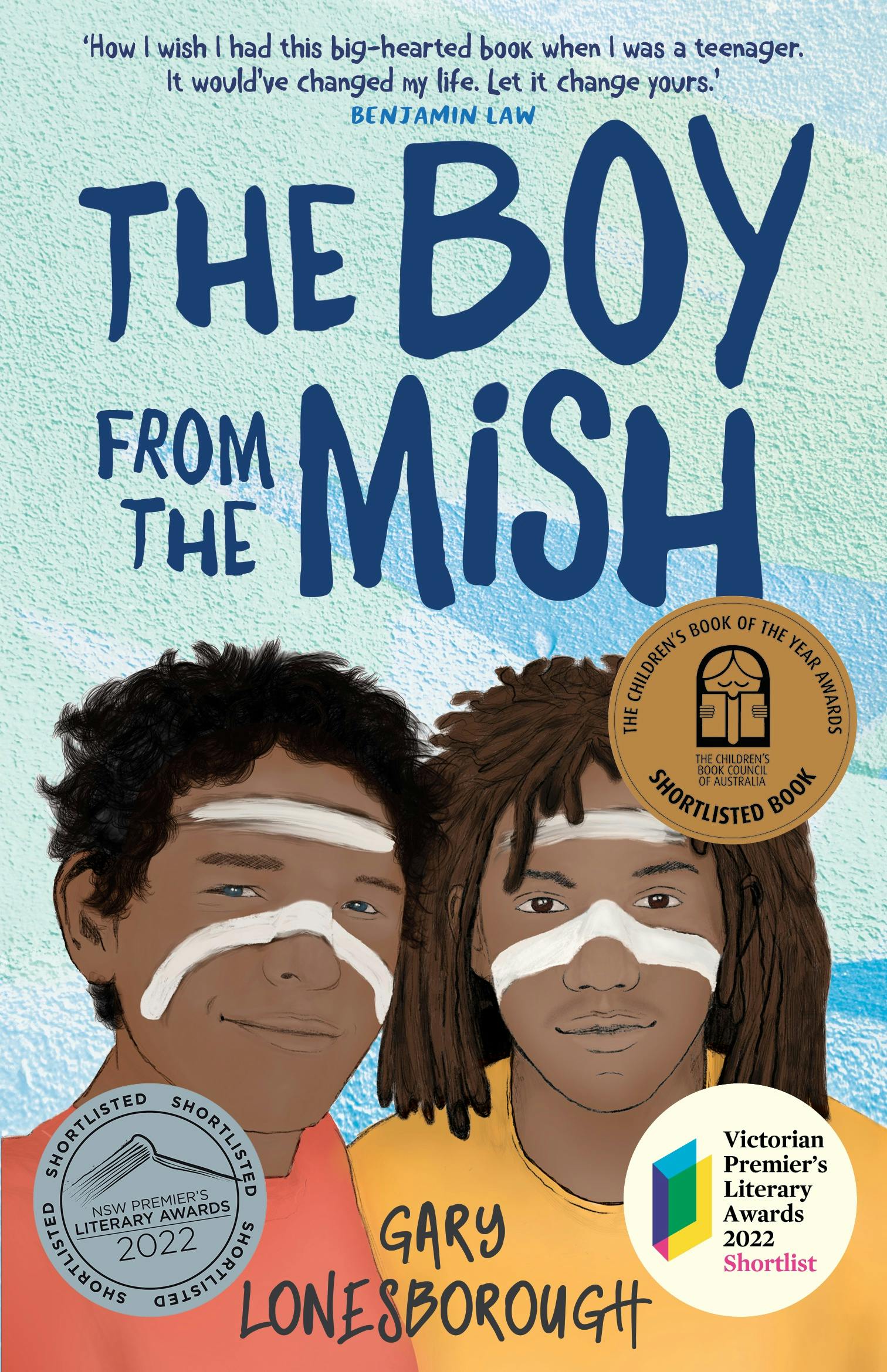

Thus it is a timely and much-needed intervention , when First Nations writers rupture what is a largely monocultural scene with their experiences of growing up First Nations, Blak and queer in twenty-first century Australia. The Boy from the Mish is the debut novel by Yuin author Gary Lonesborough.

Right from its opening line: ‘The white boys stare at us from the pub’, this story brings its readers into the First Nations community of south coast of NSW and into the realm of Aboriginal protagonist Jackson on the cusp of adulthood. Told through seventeen-year-old Jackson’s first-person point of view, The Boy from the Mish transports readers into the world of Jackson, Jarny, Kalyn, Mum, Aunty Pam, little brother Henry, cousins visiting from Sydney for the summer holidays – and Tomas, a young Aboriginal man who is in Aunty Pam’s care.

Aunty Pam, the big mob of cousins and Tomas arrive to spend the summer holidays in the small coastal town where Jackson lives. With their arrival things begin to shift, emotionally, physically and sexually for Jackson. Aunty Pam and her mob come every year to spend summer at the Mish. Lonesborough sweeps readers into the vibrancy and immediacy of Jackson’s home – where, like many Aboriginal homes across the Country, there is no such thing as a ‘crowded house’ or ‘not enough room’ when it comes to family and friends. As Jackson comes in from a party the night before Aunty arrives he ‘savours the image’ of an empty lounge room as tomorrow ‘Aunty Pam will be arriving, just like every Christmas, the house will be filled with little kids…’.

The book opens as Jackson, his cousin Kalyn and friend Jarny are heading to an end-of-year party at the Mish the night before Christmas Eve. Lonesborough launches readers into the party scene and the world of the Mish through the uncensored banter of a teenage crowd, punctuated with expletives and local lingo.

Beyond the banter and celebration, Jackson is at a crossroads – a turning point. He feels it as it pervades the mood of the party.

‘You thought about next year? ‘ Jarny asks.

‘Yeah. School stuff. Reckon I’ll just find a job somewhere.’

‘Me and Kal will still be there, but.’

‘Yeah, but you’re in Year 10 and Kalyn’s smart. I just want to get a job to make some money and get off the Mish’

Jarny finishes his beer. ‘Why? Where you wanna go?’

‘I dunno. Somewhere else,’ I say.

Jackson and girlfriend Tesha have discussed sex but it hasn’t happened yet. Tonight could be the night. Tesha joins Jackson on the lounge at the party. They leave the loungeroom and make for Abby, the host’s bedroom.

Come on, I think. Just do it.

I feel her. I think about feeling her. I think about what she wants me to do, and how much I want to do it. But fuck me, I just can’t get hard. I try to breathe slower. Concentrate.

‘Hurry up’ she whispers. And her voice sounds so sexy, I’m almost straining. I look down at her breasts. My hand is getting sore and now I’m just tired. I roll off her and lie beside her on the bed.

‘Sorry’ I say, almost gasping for air. ‘I’m too fucking drunk.’

The scene ends in an argument. Jackson lies alone on the bed after Tesha has left and wrestles with his inner thoughts.

I’m not too fucking drunk. I’m tipsy at best. And she isn’t ugly, I think she’s beautiful. Maybe my body is just broken, or maybe I’m destined to be an abstinent priest or something.

Jackson makes his way home after the party disappointed and confused.

I feel for my penis. It’s so useless right now. A letdown. Maybe it just won’t work at all.

Susan Hinton is generally acknowledged as one of the earliest writers of YA fiction. The Outsiders (1967) details the conflict between two rival gangs divided by their socio-economic status: the working class ‘Greasers’ and the middle-class ‘Socs’ (short for Socials). The story is told from the first-person perspective of teenage protagonist Ponyboy Curtis. The incidents that inspired the book took place in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1965, but this is never explicitly stated in the book.

What Hinton brought to her audiences was a story of liminality and transition – a story that is a passage, a movement that connects one tier of being to another. Hinton was fifteen when she penned the manuscript. This resonates in the voice of The Outsiders. The novel comes from inside of and is immersed in the community and the experiences of which Hinton wrote. Since then, as Kwaymullina and others have noted, the lack of diversity in YA is striking, and this is a major reason why readers from minority groups are alienated and fail to engage. In addition to this, much YA is written in retrospect by adults who despite some engaging plots, don’t often hit the mark with the transitional voice; and in some cases the sense of urgency of one who is on the cusp of liminality between late adolescence and early adulthood.

In 2020, on the eve of the release of The Boy from the Mish I spoke to Gary Lonesborough. He said he was influenced in high school by Hinton’s novel because it was written from within the moment, the time, and from the perspective of the protagonist and the characters involved. Lonesborough’s novel is rich with moments that can only be crafted from lived ‘insider’ experiences at the intersection of both First Nations and queer identities.

When Aunty Pam arrives, Jackson’s sense of self begins to shift. This year’s visit is different.Jackson wakes to the familiar sound of Aunty Pam’s horn honking outside, little brother Henry cheering as the cousins run inside, and Mum yelling to him to come down and greet Aunty.

‘My little sand-eater’ Aunty Pam says. I go down to give her a hug and a kiss on the cheek. ‘How’s your art going?’

‘I don’t really paint so much anymore,’ I say, looking at the floor.

‘Oh. Well, I got a boy who needs to do some art. You can help him out,’ she says, like I don’t have a say in the matter, like she didn’t hear what I just said about not painting so much anymore. ‘Jackson this is Tomas. He’s living with me for a while.’

Jackson is underwhelmed and irritated at his first encounter with ‘a black boy with messy curly hair, almost like dreads…’ standing behind Aunty Pam as Mum advises that Jackson will share his room with Tomas over summer. Little cousin Bobby whispers from behind to Henry, ‘…that’s Tomas. He just got out of jail’.

‘I’ll get you a mattress’ I say as he drops his backpack to the floor.

It’s thicker than those the kids sleep on, and I’m annoyed as I drag it back up the stairs. I like having my own room. I hate sharing. What if I need to fart or something while I’m in bed? Do I just hold it in forever?.

Tomas has spent time in juvenile detention. In introducing him, Lonesborough brings to the fore one of the most pressing social justice issues of our time – the ongoing colonial legacies of over policing of First Nations peoples, beginning with teenagers. As the plot unfolds Lonesborough, through the characterisation of Tomas exposes the cost of this institutional social injustice.

Jackson’s interest in Tomas is piqued despite his efforts to be despondent. On arrival Tomas presents a cool, unruffled exterior as he follows Jackson, with backpack slung over his shoulders upstairs to the room they will be sharing. Jackson leaves Tomas alone to ‘make himself at home’. Passing the doorway a short time later Jackson sees him ‘snoring away on his mattress’ on the floor. He is tempted to ‘wake him up and ask him if he just got out of jail, what he did to get in there’, but dismisses the thought and heads downstairs, ready for ‘the craziness, already able to hear the kids chattering at full volume’.

An image burns itself into my mind, of Tomas lying there on the mattress. I think I was thinking something weird when I stared at him. I think I thought he was cute.

Jackson supresses the thought and adopts a cool resolve to leave Tomas to his own thing for the rest of the summer. Inside through, Jackson senses a shift in himself that he can’t quite articulate.

Lonesborough uses a dreamscape to project Jackson’s state of flux in a scene on the beach, after Mum and Aunty Pam hijack the reluctant Jackson into taking Tomas and the mob of little kids to the lake.

I’m feeling quite annoyed today. Maybe it’s the hangover… I dunno. What I do know is I’m in a foul mood.

But his mood changes, as he watches his little brother and cousins walking to the sand:

We all walk in a bunch. I notice Bobby still wearing a bandaid on his ankle. Jude walks on one side of him and Henry on the other and they remind me of me, Jarny and Kalyn when we were younger. We were like that, always walking somewhere together.

This is one of many tender scenes of Jackson’s extended family and community that will resonate with First Nations readers.

Jackson’s mob are joined by Jarny and Kalyn who meet Tomas for the first time. ‘“You related to Jackson?” I hear Jarny ask.’

‘Nah, just living with his Aunty for a while’ Tomas replies. Jackson seizes the moment to learn more about Tomas.

‘Why are you staying with my Aunty’ I roll over and lift myself to my elbows to face him.

‘Bail conditions’ he says watching me through the sky-blue sunglasses.

Tomas heads off to the water. Jackson drapes his singlet over his head and falls asleep in the sun.

I dream a strange dream, finding myself in that space between being asleep and being awake. In this dream I am trying to walk up a staircase, but the stairs keep falling from beneath me. I run but it doesn’t matter, because the stairs just keep falling. After a while, the fallen stairs grow into a pile that I find myself on top of, as it grows to my feet. The remaining stairs, guiding the way to a door at the top, begin to fall away too. I’m stuck. I have to jump, but the courage within me is too weak.

Jackson finds himself emotionally and socially adrift. His dream articulates a liminal state of one on edge of a transition – a journey or a movement for one space/place or status to the next. Liminality is a threshold – a space that can be either an entrance or a point of departure or both simultaneously. During a liminal stage, participants stand at the threshold between their previous way of structuring and ‘being within’ their identity, time, and community; and a new passage into the future, that does not disown the former self. Rather, it is an extension – an actualization and articulation of self. Jackson’s liminality and state of adrift-ness lead to a sense of unmooring where he is unable to fully articulate himself within the shift and uncertainty he is feeling. This is the flux that drives the plot as Jackson and Tomas search for the articulation and expression of their transforming identities.

Images of precipices caused by falling stairs that once scaffolded Jackson’s identity and sense of being are central – as the staircase of a previous way of being falls away Jackson must make a leap into what appears an unknown and daunting future. There is much to negotiate in the impending change his dream predicts.

Lonesborough crafts some intense moments as he struggles with his protagonist’s isolation and emotions in a constraining heteronormative environment. The Mish is not an exception here; rather, it is a microcosm of the way our society is so binarized towards sexual orientation; and so slow and in some cases refuses the space for conversations with LGBTIQ communities and their aspirations and concerns; and for these identities to actualize.

I’m straight, I think, as I walk along the main street of the Mish.

I play through it all in my head – Mum finding out about me kissing a boy, the community knowing. They’d call me the gay lad, the fruitcake.

Jackson imagines what his cousins and friends would think if they learnt that he and Tomas have secretly kissed.

He would hate me, because I disgust him. I would disgust Jarny as well. Jarny would worry I checked him out whenever we went swimming together. He would worry I was attracted to him, that I’m attracted to him still, that I would look at him that way. I would be the one they would joke about getting the shampoo bottle stuck in his arse.

Nothing would ever be the same.

I’m not that, I think.

I can’t be that.

Not on the Mish.

Jackson’s fears of what might happen if his peers ‘find out’ are not ill-founded. Despite Jackson and Tomas’s attempts to keep their budding relationship a secret, they are found out, as they attempt to enjoy a romantic picnic together by the lake. This incident is the catalyst that unleashes ugly, hurtful homophobic prejudices that Jackson, like many other young queer people has to confront.

‘A poofter’ Jarny says, and he cuts through my whole body with the word. ‘That’s what you are right? A poofter? Or do you prefer faggot? Or maybe just homo?’

Lonesborough holds the Mish up as a mirror to and of wider society in and through this and other examples of the ignorant, hurtful and dangerous misconceptions, prejudices and stereotypes that still persist around LGBTIQ communities and people.

The ongoing significance of creative practices and storytelling as a means of connecting, growing and healing in First Nations cultures is a major theme running through The Boy from the Mish. Lonesborough skilfully plants a story within a story through the character of Tomas. When Tomas first arrives he tells Jackson that creativity is part of his recovery.

‘I’m part of this program for black kids, where they try to make you do artsy stuff to get out of trouble. I’m writing a graphic novel.’

Later when Jackson sees Tomas drawing on the beach he asks:

‘What are you writing about?’

He sighs and stops writing. ‘It’s a sorta like a superhero origin story. But I want it to be unique. And I’m a shit drawer so I thought the weed might help. I’ve kinda got a story but I dunno.’

Tomas explains to Jackson that the point of the program is to show the judge (the caseworker) that he is ‘getting better’ by putting his energy into something creative.

‘But it’s hard because I can’t draw for shit. I like to write, I guess. I think I’m alright at writing’ His voice sounds higher somehow.

‘Well, you don’t need weed. Maybe I can help you’ I say. ‘With the drawings, I mean.’ I almost stop but continue. ‘I used to be a pretty good drawer. Maybe you just need to see your superhero as a drawing first so you can really know who they are.’

When the drawing is complete, Tomas tells Jackson he’s a ‘good drawer’. Jackson feels,

‘….a different kind of warm – one that doesn’t radiate from the sky; one that radiates from somewhere else.

‘Do you know him now?’ I ask.

‘I think so. He lives on the Mish. There’s some threat, and he has to save all the children.’

‘What kind of threat?’

He hums for a moment. ‘Not sure yet.’

Through the story-making process of the graphic novel, Jackson and Tomas are also making their own story. Simultaneously Jackson’s mother and Aunty Pam resume painting a large artwork that they have been working on together every summer for years. These creative productions are interwoven within the central plot of the novel and parallel the growth and changes experienced by the characters involved. The graphic novel of the Aboriginal superhero continues to grow and develop through the narrative and so does the relationship between Jackson and Tomas as they write and draw themselves into the actualization of a new way of knowing and being.

The Boy from the Mish resembles The Outsiders in terms of both authors’ capacity to harness the immediacy and urgency of voice. But there are several distinctions between First Nations YA and settler works in the same genre.

In 2019, Wulli-Wulli author, Lisa Fuller released her debut YA novel Ghost Bird. The plot centres around a small town in western Queensland that is the home of twins Laney and Stacey. Although mirror twins, Laney and Stacey have very different dispositions and attitudes. Stacey loves school and wants to work hard and get out of town. Laney hates it, sees it a major waste of time and energy and frequently truants to spend time with her boyfriend. One night Laney goes missing after a night out with her boyfriend. The narrative revolves around this disappearance.

Although the plots of The Boy from the Mish and Ghost Bird are different there are some underlying similarities across these two First Nations YA narratives that distinguish these works and other First Nations’ authored YA from those written from settler cultural contexts and perspectives. Jackson in The Boy from the Mish and seventeen-year-old Stacey in Ghost Bird are both firmly grounded in First Nations culture and history through Elders. Jackson regularly attends a Men’s Group run by Elders to keep culture strong and to nurture intergenerational connection between Elders and youth through the passing on of history through painting and story. Fuller’s work begins with a story told to Stacey and twin sister Laney by their Grandmother that reoccurs throughout the narrative and provides clues and signs to the whereabouts of the missing Laney.

Both works use dreamscapes as a way of articulating the consciousness of the protagonists and pre-empting events to come. Just as Jackson’s dream pre-empts the journey to a new identity, Stacey’s dream pre-empts the disappearance of her sister.

I’m wrenched into semi-consciousness, fear pouring over me. I’m sure, so horribly sure, that Laney is in danger. Struggling out of my suffocating covers, I stagger, right myself, wobbling my way to Laney’s bedroom door, and slamming it open. The bed is messy as usual and there’s no way to see if a body is lying in it. I land on the thing, hands dragging through blankets and emptiness.

Re-occurring dreams throughout Fuller’s novel reveal clues to the whereabouts of her missing sister.

Both authors question and critique, Fuller openly and Lonesborough indirectly, the Freudian view of dreams. Stacey, despite her best efforts as a teenager to ‘believe more in science that than her own mob’ is haunted by her Grandmother’s words as she tries, initially to dismiss her dreams.

Nan would probably have called it a special dream, one I should listen to. School says it is my subconscious telling me something about myself, although why the hell I would dream I’m Laney is anyone’s guess.

That nightmare, but. It felt so freaking real.

A notable feature of First Nations YA that differs from Anglo-Western post-Enlightenment writing conventions in what can be loosely defined as ‘coming of age’, debut, bildungsroman or ‘rites of passage’ narratives is that intergenerational spaces and dialogue between adults and adolescence are less segregated than in settler works. The communication between generations is less stratified and the spaces between adults and young adults are more fluid. While each protagonist experiences angst (and loss for Stacey in Fuller’s narrative) they are grounded in something more than youth subculture.

Elders feature strongly in both books. Stacey’s Grandmother, although no longer physically in the world, is a strong presence throughout the narrative. While a major transition and transformation occurs for Laney and Stacey, the novel ends, after much action and intrigue, where it began with Stacey feeling safe for the first time since her sister’s disappearance.

I fall asleep with Mum’s arms and Nan’s presence surrounding me.

In the closing chapters of The Boy from the Mish Jackson’s Elder, Uncle Charlie approaches Jackson at the Men’s group. Uncle Charlie reassures Jackson of his connection and place in the community.

All I’m saying is that we are connected, all of our people, even if sometimes you don’t feel like it – we are all connected.

Uncle Charlie goes on:

‘There’s this shame’ he continues. ‘It took our people by the throat a long time ago. If we don’t let ourselves be who we are, love who we are, where we come from, it’ll strangle ya until you can’t fight no longer. You know what I’m saying, Jackson.’

Jackson tells Uncle Charlie that it is ‘really hard sometimes’:

‘All right’ I say, but my voice quivers. ‘But can I still be connected? If I’m…you know?’

‘There’s nothing that can keep you from your culture, if you truly want it,’ he whispers.

Uncle Charlie stands and I stand with him. He wraps his arms around me and we hug. It’s the best hug I’ve had since Tomas left.

The blurring and melding of the lines of communication between adults and adolescents in these and other YA works by First Nations authors lends itself to an interconnectivity across genre as well. The labelling and marketing of these works as YA reflects the persistent and constraining use of labels and binary categories in the publishing industry, a practice that often undercuts and underrates the capacity of these and other First Nations narratives that have teenage or young adult protagonists to connect across generations.

While neither work is autobiographical, they are both works of realism. First Nations writing by young authors depicting young protagonists does not just tackle one single issue as appears to be the formula for much settler writing for youth. Lonesborough’s and Fuller’s works confront many prevalent and pressing issues impacting on the lives of First Nations youth. Issues such as over-policing, individual and institutionalised racism, settler privilege and prejudice, lateral violence, are all interwoven within the central plots in a way that resonates with the lived reality of First Nations communities intergenerationally.

The protagonists in both these narratives move between two worlds – the world of the First Nations community in which they belong; and the world of settler colonialism that we all must engage with by default with agency. Neither Jackson or Stacey are inarticulate or timid in expressing themselves as First Nations youth to the settler world; and neither struggles with English – a common and persistent trope of settler deficit discourse levelled at First Nations writing and writers. But each character is firmly grounded in one culture – the continuing culture of First Nations peoples through story, that sustains them through their daily and necessary interactions with the settler world.

In both works, as in many other First Nations works, white-settlerism is ‘the other’. Neither author feels the need to over-explain or ‘dumb down’ the beliefs, practices and stories of their respective communities for a settler audience. The realism of Aboriginality and First Nations culture in the twenty-first century is centred and sustained.

Jackson emerges at the end of the novel re-grounded and strong in his identity and culture as a First Nations young queer man. While Jackson’s journey is still unfolding at the end of the novel he has made a few important decisions for the future.

‘I’m glad you decided to go back to school’ Mum says as we park the car at home.

‘I just want you to know how proud I am of you for deciding to finish Year 12. It was a very mature decision.’

In the closing scenes of The Boy from the Mish the graphic novel is still a work in progress and an important point of connection between Jackson and Tomas when the summer holidays end.

‘…I wrote the story and did some of the sketches, but I was thinking you could redraw them since you’re a better drawer?

‘Yeah’ I say, I’ll do it. Just mail them to me.’

‘You sure?’

‘Yes, I’m sure.’ I wonder if he is smiling as widely as I am.

In recent interview with Guardian Australia, Lonesborough spoke of his isolation as a teenager from the world of YA fiction because he could not see himself, or his community or his sexuality in any settler narrative. This was his powerful, driving motivation for the rich creative offering that was brought to fruition in The Boy from the Mish. In endorsing the novel, Benjamin Law described it as a ‘big hearted book’. It is. But it is more than that. It is a book that says to all readers of First Nations YA – I’m here! I’m real! And you are too.