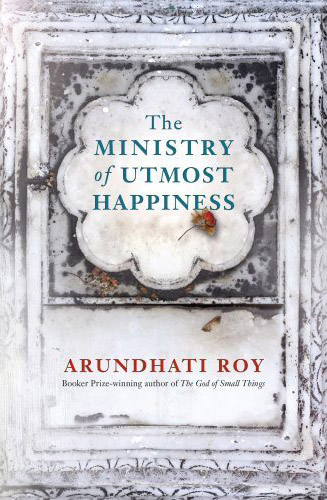

It was twenty years ago when Arundhati Roy’s Indian pastoral, The God of Small Things was published. The novel was an immediate success, won the Booker, sold exceptionally well, was translated into 40 languages and gave the author financial security. It followed a key principle of the genre of the pastoral – transforming the complex into the simple – as if Virgil’s Georgics were transformed into a novel.

But more than the generic transformation it was a statement about love as the one immutable and organizing principle in our lives. Twins Rahel and Estha return to their home in Ayemenem, Kerala, and recall events that happened so many years before. These were tragic events but they are recalled very much within a symbolist mode of composition where metaphors would be connected, where a moth would reappear to make poetic connections, where small things, small wisdoms mattered and where ideology would play second fiddle to the aesthetic. The intertexts recalled – Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, the musical The Sound of Music – would be stripped of their political power and offered as affects, memory’s anchor points: no Caliban with his cry of dispossession but the songs of Ariel; no French Revolution but Charles Darnay’s Humphrey Bogart-like aphorism; no Nazis but Julie Andrews’ singing, no Rushdie with a sense of loss but the Braganza Pickles reappearing as Padma Pickles in Bombay, no Conrad but the descriptive heart of darkness.

The novel drew our attention to complex things – casteism, corruption, environmental abuse (a river where the fish had died), misplaced Marxism and much else – but it was the joy of writing – those marvellous metaphors, the exceptional mastery of the language that made The God of Small Things so remarkable. It felt like ‘a grey pebble in a mountain stream – something icy rushed over it’ and it spoke like the breeze, as it captured virtues celebrated by Italo Calvino: lightness, quickness, exactitude, visibility, multiplicity and consistency. A writer of that calibre, twenty years on, would surely write something exceptional – but sadly this is not the case with The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. The analogy is forced but it is as if a socially aware and a critically incensed Shakespeare were writing The Tempest, The Merchant of Venice or Othello (and what a loss that would have been). It is as if the naked Murlidharan in The God of Small Things, standing alongside the Communist March with a plastic bag on his head and a bunch of keys tied around his waist, screamed obscenities. And Murlidharan, at least, would have had real cause to do so.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness begins with a powerful image, which may be read as its epigraph and summation. As the evening dawns, bats release their grip and fly out of banyan trees in the graveyard; crows return to replace them but there is an eerie absence: sparrows have gone for good and vultures, ‘custodians of the dead,’ too. Vultures feed on dead carcasses, human and animal; but dead carcasses are now lethal because cows fed on cow-aspirin so as to produce more milk turn into poisonous baits when they die, and the vultures feeding on them drop dead. Something has gone dreadfully wrong and this is not simply things falling apart or something rotten in the state; something has gone wrong in the moral fibre of humanity; what made us human, our connections to the larger ecosystem have been fractured.

Where then to begin if the centre cannot hold? Roy goes to the margins of Indian life and to the limit situation of Indian social life, to the eunuch, better known as hijra, seen by many as a world apart, neither transgender nor bisexual, as if nature had created something unnatural, grotesque, and then mechanically reproduced it. And so perhaps it is only in the margins of social lives one can see some hope, one can find love, a quality currently bereft of meaning in India.

The life of a hijra frames the novel’s principal narrative, a tale of three men in love with the same woman in the context of India’s moral dilemma in Kashmir. The hijra narrative, if we wish to call it that, begins with Aftab who arrives as the longed-for son in the Mulaqat Ali and Jahanara Begum family of successive girls. But joy turns to despondency as the boy is hermaphroditic and prefers the company of women. As he grows older he takes on the female role of a hijra, calls herself Anjum and finds solace in the company of other hijras who lived in Khwabgah, the ‘Abode of Dreams’.

Now with a female identity, at 46 Anjum leaves this hijra household and, with the help of like-minded people and an Untouchable (Dalit) convert to Islam (who calls himself Saddam Hussain), establishes a commune in a decrepit graveyard. This location is an inversion of Plato’s cave: the cave/graveyard has light while Duniya, the world outside, the world of ordinary people, is the world of illusion and darkness, of ignorance. Gradually the graveyard becomes a hub of activity, a home and a guest house whose pir, or holy saint, is Hazrat Sarmad Shaheed who was beheaded by an irate Mughal Emperor for daring to challenge orthodoxy.

Things, however, are amiss in Duniya. Delhi is heavily polluted and Muslims especially are singled out for abuse, including the dreaded vasectomy of males during the Emergency years. In a society that has lost its soul and whose leaders are either loquacious poets, puppets or genocidists (Atal Behari Bajpayee, Manmohan Singh and Narendra Modi, the ‘Gujarat ka Lalla, Gujarat’s Beloved,’ are severely caricatured throughout the novel), Anjum finds solace in Zainab, a lost baby girl she collects at the Jama Masjid. In these small gestures of love, one finds some relief, for without them a nation run by ‘saffron parakeets’ and cow-worshippers has no moral core at all, no sense of ethics. The critique of The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is unrelieved and relentless: the Hindu, the dominant community in India, seems to have lost its own tradition of tolerance.

If the hijra world provides one narrative, the other comes from the kind of narrative interconnectivity that Arundhati Roy is especially good at. If Anjum’s world of the graveyard is one centre, the other is a bourgeois, middle-class world of four people who come together as students of Delhi University on the set of a play. Two, Nagaraj Hariharan (Naga for short) and Biplab Dasgupta, are actors in a play, Norman, Is That You?, in which one of the characters is called Garson Hobart. The name sticks with Biplab. The year is 1984, the times are out of joint and the play has to be shelved because all around Delhi Sikhs are being indiscriminately slaughtered in revenge for Indira Gandhi’s assassination by her Sikh bodyguards (O Hindustan will you ever be at peace with yourself? Will the ‘saffron tide’ rise ‘as the swastika once did in another’?) The other two, a woman S. Tilottama (Tilo for short) from Kerala and Musa Yeswi, a Kashmiri, are architecture students.

Garson Hobart functions as an anchoring point in the narrative (he alone is given a first person voice) providing Tilo with help (lodging, reprieve from accusations of being a Kashmiri insurgent supporter) and surfacing as a government functionary in Kabul and Srinagar and as a landlord in Delhi. Naga, always in love with Tilo, even after hastily marrying Lindy (who turns out to be an Australian drug addict) could at least sing the Stones’ ‘Symphony for the Devil.’ Tilo does finally marry Naga, a journalist and another anchoring point for the narrative, but only because now that Musa is dead she needs a carer of sorts. She remains with him for fourteen years until she too with her adopted child Udaya Jebeen II enters Anjum’s world.

And there is Musa, temperate, controlled, somewhat detached, considerate and without hate. The novel has other characters who fight for a cause – women, Indian Aborigines, Dalits – but it is Musa’s commitment to Kashmir against Occupation forces – Musa who ‘had lived a life in which every night was potentially the night of the long knives’ – that propels the narrative towards its tragic end. And so Tilo will make her way to Kashmir to be with Musa, whose wife Arifa and daughter Jebeen were shot by soldiers as they watched a procession from their balcony, and see for herself the devastation wrought by indiscriminate killings by soldiers.

Tilo will make amends by adopting her own child, and this Jebeen (named after Musa’s daughter and hence called Jebeen II) would be an unwanted child of collective violence on a woman-soldier-insurgent who dared to fight for her own Nagaland. Brutality breeds brutality; humans typify nations. In a killing spree in Kashmir, by morning ‘the count had risen to nineteen … [the dead carried] on their shoulders to the Martyrs’ Graveyard’; this is a mocking replay of the other, pastoral graveyard domesticity of the hijras. One especially sadistic soldier and interrogator, Major Amrik Singh, code named Otter (for ‘Spotter’) will end up in Clovis, California killing his wife Loveleen and himself.

The hatred of Indians, we are told, is so visceral that Roy can create a Kashmiri-English Dictionary that, when read alphabetically, offers a narrative of a Kashmir where ‘you can be killed for surviving’. Why? Because agents, informers, interrogators, jihadists, soldiers, lovers, husbands, parents were all part of a world in which, recalling Adorno’s words on the Holocaust (‘there can be no poetry after Auschwitz’), ‘There’s too much blood for good literature’. This is the subtext of this seething tale of a crisis in the collective psyche of a nation that is rudderless, insecure and possibly mad. These points are made with power and force throughout The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, where the joy of reading inheres not in the content but in the discourse itself.

Arundhati Roy is at her best not when she parodies politicians, social practices and policies, not when she engages with the Union Carbide disaster, not when she correctly draws attention to abuse of power by the military in Kashmir (which she effectively reads as a ‘Palestine’ under Israeli, here Indian, Occupation), but when she uses anecdotal narratives (a remarkable narrative device celebrated in Indian narratives generally). Middle-class Delhi men, throwing razors at a hippopotamus in a zoo, taking delight in the animal’s pain, say more about depravity than descriptions of torture because the act of throwing razors to an animal (for food!) in a zoo is neither determinative nor reflective reason; it is absolute barbarism if not absolute evil. The symbol is carried over with the reference to Musa’s daughter Jebeen’s ‘beloved stuffed (and leaking) green hippopotamus’ awaiting for Jebeen’s bedtime story as the soldiers come for Musa. And then there is the description of the Untouchable, the Dalit soldier S. Murugesan whose body is sent home to Kerala. A statute is built in the village in his memory. But soon the statue is destroyed because a Dalit cannot be celebrated; his sacrifice is not Indian, he just does not belong to the nation; he is intrinsically incapable of heroism.

These instances take us back to the greatness of The God of Small Things because suggestiveness, innuendo, the slanted were the expressive modes there. And even in this novel the suggestions that perhaps Tilo’s parents were in fact Ammachi Maryam Ipe and her Dalit lover Velutha, that Lieutenant Colonel Stalin, head of the army’s human rights cell was a ‘friendly fellow from Kerala’ and therefore a version of Lenin, son of the Marxist leader in her earlier novel, pay indirect homage to to Roy’s debut. The expressive power of that first novel returns in redemptive strains in the epigraph to The Ministry of Utmost Happiness where we read of the final night shared by Musa and Tilo, of the couple entwined in an embrace in the Jannat Guest House of the graveyard before Musa departs to die in Kashmir. The cameo scene is followed by another cinematic shot of Anjum and Udaya Jebeen II walking through Delhi streets. Hope is there but perhaps it is a little late.

There is wonderful Urdu poetry in the novel suffused by strains of Indian classical raga – a Lalit here, a Kalyan or a Tilak Kamod there; there is also exceptional descriptive prose, some so appealing that one wishes the descriptions would continue and the narrative momentarily halted for the reader to take in Roy’s prose-poetry, ‘to pluck the very stars from the sky and grind them into a potion’. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is a complex novel; its theme nothing less than genocide and a scorched-earth policy. This agenda is self-evident, even if overwrought. Nothing wrong there. But as novel qua novel (an incorrect symbolist proposition on my part let’s accept) ideology and commitment displace irony and detachment. And love gets slanted; it is found only in the margins, in the lives of hijras, in the lives of lone protesters and marchers, in the revolutionary fervour of Kashmiris fighting for unification with Pakistan (a point never acknowledged by the narrator for whom Kashmir, like Tibet, belongs to someone else), in the sad line of mourners in the Martyrs’ Graveyard, the Mazar-e-Shohadda (where the cast-iron signboard is ‘silhouetted like a swatch of stiff lace against the sapphire sky and the snowy, saw-toothed mountains’), in Tilo’s love for Musa and in the urn with the ashes of a mother who was denied proper Syrian Christian burial because of her love of an Untouchable.

Although not in the genre of hysterical realism Arundhati Roy’s novel becomes hysterical and lopsided. Fiction becomes subservient to ideology and simple allegory becomes its mode, the pastoral which could channel the complex into the simple is gone. The novel is a genre in the making, this much we know; it is a crucible for metaphysics as well as history; but its heart, its soul lies in itself and in its capacity to undercut monological points of view. Sadly the undercutting is missing and the ideological celebration, the activist impulse, is all one-sided. There is no acknowledgement of a nation desperately trying to hold itself together.

And in the end Arundhati Roy’s novel, powerful, evocative, relentless in its critique of injustice as it no doubt is, shows no love for a nation that has made her own writing possible, her own voice heard and also defended in many quarters. Troubled as they were by their own nations, neither Dostoevsky, nor Joyce, nor even Rushdie, each lesser than Arundhati Roy but greater, showed such hate towards the nation of their birth.