Responding in Aboriginal English, Wunyeran refutes the depiction of suffering in hell as a valid representation of the afterlife. He mixes Noongar syntax with English words, and specifically uses the image of a port, one of the signs of colonial warfare and trade, to warn about the dangers of Christianity. Wunyeran’s enigmatic statement suggests that if a different port, or alternative theological structure, had been chosen by settlers at King George Sound, something other than the series of massacres and attempts to erase Noongar people and their culture may have resulted. While Scott’s novel isn’t structured around a series of theological propositions, Wunyeran does provide an unequivocal warning about Christian depictions of the afterlife being used to justify violence. Charlie and Joe propose a similar set of reforms to Christian eschatology, albeit in the language of 1960s Fitzroy. Charlie’s critique of the nun’s use of hell to terrify children allows both he and his grandson to participate in an ongoing Aboriginal conversation regarding Church reform. Birch’s inclusion of children within these theological discussions – and the seriousness of the grandfather’s engagement with his grandchildren – is also vital to the overarching structure of the novel.

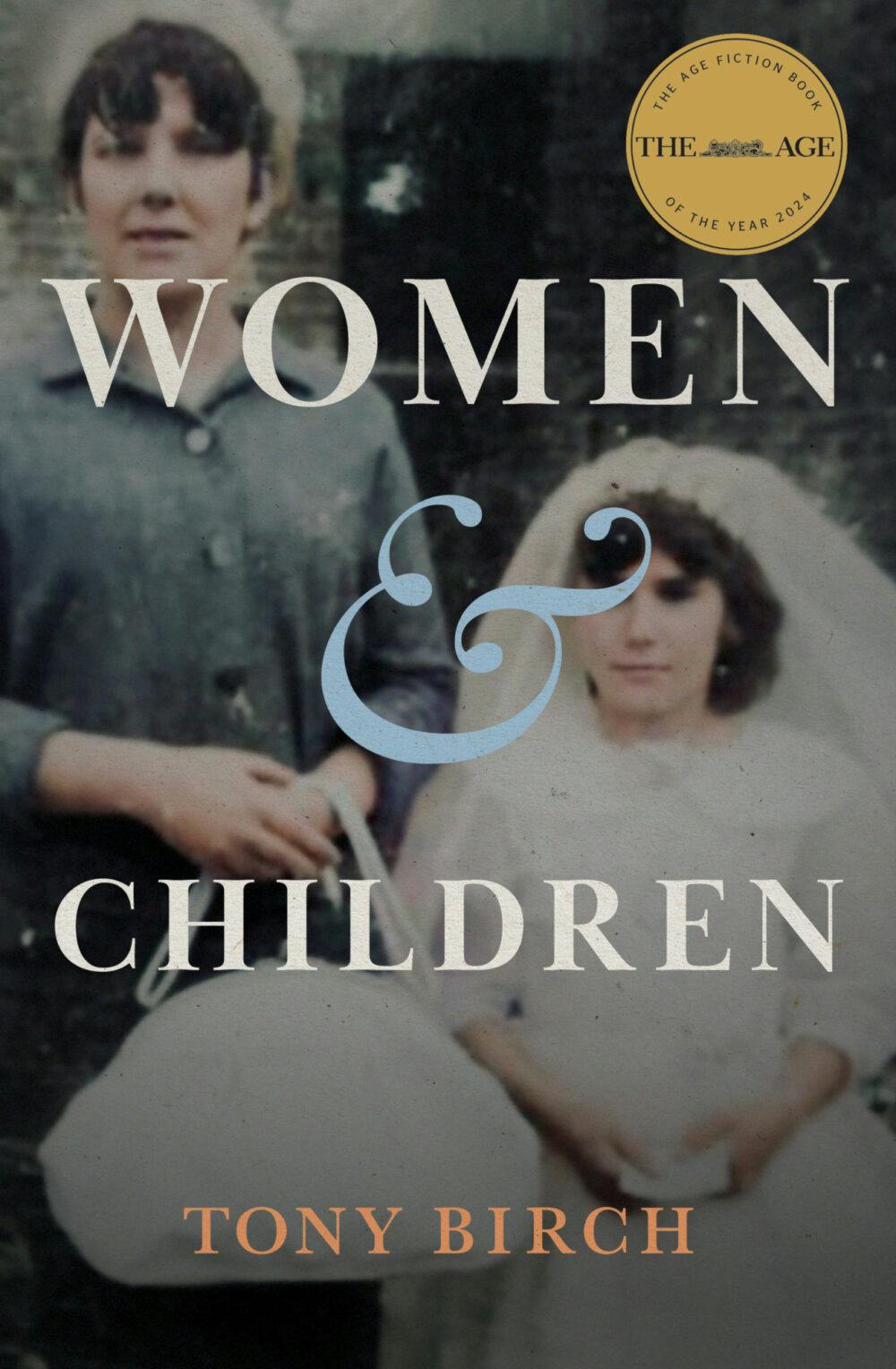

In Women and Children, the grandfather’s role in the family is defined by the labour of childcare, and the possibilities for conversation that emerge while engaging in collaborative, repetitive tasks. Just as Scott’s fiction does not aim to provide solutions to political problems, Birch’s novel does not issue a program for dealing with domestic violence in Australia; rather it draws the reader’s attention to the contexts, institutions, and ideologies which sustain this form of violence. What the narrative of Women and Children offers is an alternative to domestic violence: male domestic labour, and the possibilities for quiet discussion that come with this work.

Not all forms of quietness in Women and Children, though, are positive. When Oona first arrives at Marion’s front door, her speech evaporates. As she attempts to ask her sister for shelter while keeping her injuries concealed, we hear that ‘Oona’s free hand was shaking, and her mouth was slightly open. It was as if she wanted to speak but was unable to do so’. In Women and Children, women do not have to speak loudly to be heard. In the wake of the first round of Oona’s abuse, the family, the church, and the society are calmly interrogated by Birch for their complicity in her situation. Birch does not demand that Oona’s silence be turned into articulate speech. By focusing on critiquing the institutions that fail to acknowledge domestic abuse, Birch offers a framework for rethinking familial structures in terms of domestic labour and the ongoing conversations which can hold families together.

Lynda Ng has argued that Women and Children is not a work of nostalgia – Birch uses 1960s Fitzroy to address the present. ‘Domestic violence’ does not come into common parlance until the 1970s, and while there is little consensus between our legal system and women’s rights organisations about what is encompassed by the term and how to prevent it, the problem of violence against women by their partners is escalating. The new coercive control laws in New South Wales criminalise behaviours such as verbal and financial abuse, which have long been understood to be not only indictors of worse crimes, but also some of the most damaging experiences for victims. However, there is also evidence that increased legislation does not decrease violence. In Australia, a woman is killed by her husband, boyfriend or ex-partner every week; last year the average was slightly higher. Research suggests that climate change is likely to increase rates of domestic violence: in periods of uncertainty and economic depression, women are not only more likely to be harmed, but the society is also less willing to hold their perpetrators accountable. Aboriginal women are thirty-two times more likely to be targeted. As Birch reminds us in his 2023 essay on Alexis Wright for The Monthly: