1

Philip Roth. During my formative years, when I was still a baffled undergraduate, this was a magical name amongst the friends I counted as readers, and even to older acquaintances a generation removed from our contemporary gods but not so dismissive of the notion of greatness as to not bend at the knee to the prowess of a novelist in the highest flight. The name was magical; so too the unmatchable prose. Of the few elder statesmen of literature still sailing in present waters, none possessed anything remotely like the aura of permanence of this reclusive yet omnipotent Master.

These words, in a slightly different form, belong to the opening page of American Pastoral (1997).

2

Pastiche is one way to get started; quotation another.

‘Fear presides over these memories, a perpetual fear.’

That is the opening line of The Plot Against America (2004). Simple, and for late Roth, almost a mission statement.

3

When interviewed late in his career, Roth was frequently at pains to describe the bafflements of conception, almost in atonement for the growing monument slowly surrounding him. He would talk of the false starts, the hundreds of pages of waste in search of a first line or an animating concept. This struggle would be insisted upon. Every novel was a birth from blankness. He was trying to make a point. Yet the novels continued to arrive. We would have to accept his word about the struggle.

4

The struggle now appears to be over, with the announcement in late 2012 that with the publication of Nemesis (2010), Roth had retired. Perhaps the struggle was no longer sustainable. What does it even mean for a writer to retire, particularly for someone as committed to their art as Roth? Athletes retire because their bodies refuse to perform the old deeds. They either pick just the right time and leave with images of prowess and dominance fresh in the mind, or back themselves in for one year too many and become patronised examples of greatness gone to seed. Artists, comparatively, can work into old age, particularly writers, even if they slow down. The need to announce retirement – to finalise it, to snuff out all hope – is odd.

Still, amateur psychoanalysis will not be entered into here. Well, not much. Not intentionally.

5

Nonetheless, the retirement gives us a certain finality to critical statements. There won’t be a new novel along any time soon to undermine finely calibrated judgements. What’s left is all we have. There is presumably no equivalent of Vladimir Nabokov’s unfinished, posthumously published novel The Original of Laura (2009) – which is barely a first draft, hardly a sketch – waiting for us in the decades to come. Retiring like this allows Roth to control his legacy, to round out the remaining years. Reportedly, a biography is on the way.

6

In late December 2012, an unverified Philip Roth Twitter account appeared. Despite the first and only tweet containing an elementary grammatical mistake, it was widely reported and swallowed whole by people who should have known better. This might be an example of desire outweighing logic. Roth was fond of this topic.

7

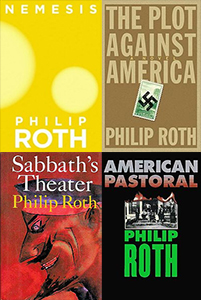

Roth was recently asked by the Guardian to name his finest novels. Choosing Sabbath’s Theater (1995) and American Pastoral, he confirmed the titles most often found in the tributes and eulogies-to-the-living that flooded the literary community in the wake of the announcement.

8

It is something of a misnomer that the Roth novels that garner so much of the praise are called ‘Zuckerman novels’, given that the later books, particularly those referred to as ‘The American Trilogy’, are defined by that character’s absence. In American Pastoral, I Married a Communist (1998) and The Human Stain (2000), Zuckerman becomes an audience. He is like someone who goes to a party assuming he will be the most interesting person there, only to stumble into a casual conversation that opens up someone else’s extraordinary life.

9

If there’s a single fact about Roth that cements his position in the kingdom of American letters in the minds of most, it is his recent canonisation in the Library of America edition. As is often noted, he is the first living author to receive this honour. If this sounds a little ghoulish or contradictory, like building a statue around a living model, and casts the work in a similarly dead-but-breathing light, it is worth pondering for a moment just how variegated and odd much of that work is when viewed in its totality. There is the curious political satire Our Gang (1971), the dialogue-only European intensity of Deception (1990), the curiously Gogolian sketch calling itself The Breast (1972), and that deliberately shaggy and wandering puzzle The Great American Novel (1973). The second Zuckerman trilogy, in its excellence, its sweep, its summarising power, tends to blind people to how contested Roth’s position in American letters was for a long time. And that for a long time a single work dogged him, the literary equivalent of a band obliged to play their solitary hit. My copy of The Counterlife (1986) needlessly tells me it is ‘from the author of Portnoy’s Complaint’.

10

Retrospective wisdom allows us to turn failures into success; every book is a success to some reader. It is possible for a generous interpretation to see in the failed early work intimations of the greater work to come. All roads leads to triumph and a kindness is extended to your past. All the writer has to do is make sure the greater works do arrive.

11

The first Zuckerman trilogy earns the label that is often applied to writing that risks the over-personal: self-indulgent. Written as a reaction to the success of Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), Roth invented for himself a writerly persona, who in turn wrote autobiographical novels. Roth was Zuckerman, Portnoy’s Complaint became ‘Carnovsky’, and out into the world rolled the first trilogy – plus an excellent and rarely remarked upon novella The Prague Orgy (1985) – notable for its frequent descents into the hysterical, the panicked, the neurotic, the barking.

12

From a review of Zuckerman Unbound (1981) by Martin Amis:

This is a new kind of autobiographical novel. It is an autobiographical novel about what it is like to write autobiographical novels … The question is: do we need this kind of autobiographical novel? We all seemed to be getting by without it.

13

Much of Roth’s writing in this middle period of his career has a belligerent, inward-looking energy. Consider The Anatomy Lesson (1983), the third book of the first Zuckerman trilogy. While frequently hilarious, the engine that powers much of the novel is fuelled by nothing more than resentment – specifically, Roth’s attempt to settle the score over a vicious Irving Howe article originally published in Commentary. The desperate comic riffs on illness and existence are typically vivid and compelling, but long sections of the book are grossly unfair and mocking, pushing what he sees as quaint Jewish decorum into the realms of pornography and egotism, and all over a bad review. What else was there to write? A critic can only ever review the book that was written, but much of Roth’s writing around this time feels like the literary equivalent of Stirling Moss doing donuts in a suburban Coles car park.

In Operation Shylock (1993), not even the Israel/Palestine conflict could produce a fitting solemnity. Instead, Roth saw it as a chance for ribaldry and impersonation. The whole debate is seen in terms of heat and dust, as pure noise, rather than anything serious, or ponderous, or self-regarding, or (worst of all) pontificating. The politics – the agony and uncertainty, the contradictions – is felt not on literal, but literary lines. Roth tended to treat the intractable with mania, a conquering counter-energy. He refused to be baffled by it. He shouted it down.

Meanwhile, the Philip Roth who lived in the real world edited Penguin’s ‘Writers From The Other Europe’ series, a publishing idea that brought writers of enormous talent, such as Aharon Appelfeld and Danilo Kiš, to the attention of an English language readership for the first time. The wily Philip Roth of the fictions, that blazed doppleganger, misbehaved and lived only for himself. One was a good citizen, a private man and a writer. The other was a bad husband, a show-off and a writer.

14

There is an uneven tone to the work between Portnoy’s Complaint and the masterpieces of the 1990s – and this needs to emphasised: the run of novels beginning with Operation Shylock and ending with The Human Stain is a phenomenal stretch of work – but what has frequently been overlooked in coverage of Roth’s retirement are the novels of the last ten years of his writing life, starting with The Dying Animal (2001) and ending with Nemesis.

There was something patronizing in the reception of many of these novels. Many found Roth’s productivity in this late period of his career salutary and inspiring, but this attitude – which regards a novel with the same mildly condescending air that greets retirees still out and about with their social lives – has its downside. The received line on Roth’s later work now seems to be that it is a heartening burst of greying vitality that we should be grateful for, but also that it is, on a book-to-book basis, nothing that contributes to his lasting legacy.

15

The Dying Animal (2001) requires no such caveats. Despite its brevity (150 pages) it is an extraordinary achievement, and perhaps Roth’s finest and least resolvable novel of sexual politics. In much the same way as an older and wiser Zuckerman was called forth to stand witness in the later trilogy, here Roth gives us a greyer but still lustfully undimmed David Kepesh – last seen in The Professor of Desire (1977) – a man bereft of connections due to his relentless philandering, yet unapologetic in his behaviour. That Kepesh is such a knowing presence, and so skilled in the art of self-exculpation, only complicates matters. Staged as both a confession and a historical lesson in the sexual revolution, Roth gives us a different version of Mickey Sabbath – one who walks a fine line between detached consideration and ruin. He charts how desire overwhelms all, even a man who has spent his entire life finding pockets in the culture where his behaviour might fall under the banner of liberation and not narcissism. The object of his desire, Consuela, is more erotic reverie than believable presence, but this is all the better to undo Kepesh, who in the novel’s final pages faces a possibility he has spent his entire life avoiding: responsibility.

16

That Roth’s excesses were often lumped in with the frequently dismal sexual politics of Norman Mailer and John Updike always struck me as unfair, and a misreading of the work. That his characters were frequently outrageous or cruel or monstrously selfish was always tempered by the comic unreality of much of his sexual writing, and by the frequently dismal consequences for his characters. These books do not indulge an archaic sensibility, but rather represent it without illusions, and nowhere is this distinction better illustrated than in The Dying Animal’s tension between libido and duty. Updike’s characters float on serene waspish clouds of nervy adultery; Mailer’s grunts act out their borrowed Hemingwayisms. Roth goes further and collapses the entire apparatus. Whatever sins his unthinking men might have committed in the past, however buffoonish they seem, however much they are written with an eye towards the comedy of exaggeration, The Dying Animal tempers it, apologises, complicates. Illusionless, perhaps, in its view of ageing male sexuality, but never false.

17

If the second Zuckerman trilogy allowed Roth to stage his human dramas against a backdrop of national concerns – Communist scares, racial identity – then The Plot Against America goes those novels one better: it imagines a drama both unreal and entirely believable. What if fascism was a genuine American possibility; what if it moved beyond the private grudge into the realm of the law, of the politically viable?

The Plot Against America is incongruous in this period of Roth’s career, surrounded as it is by books of a more contained energy, their dramas acted out on a smaller stage. It is by far the longest book of the final seven, and the most traditionally ‘rounded’ and plotted. But that word: plot. Rereading the novel, you can forget how lightly plotted many of Roth’s novels are, and how often the inner warp of mania and monologue (forever its own kind of drama) acts as a substitute for the more conventional realm of dramatic action much of the time. Here it is a carefully constructed world, one of slowly mounting terror, neighbourhood unrest, familial pressure. What the novel does best of all is revisit youth as a time of terror – like a history lesson learnt twice by the same child, with all the echoes and barely-missed possibilities only registering second time around. In The Plot Against America, unlike Operation Shylock, there is not a trace of playfulness. The conceit only strengthens the strange credibility of the book. It is common enough to revisit the world of childhood and comprehend too late the continual danger you somehow managed to avoid on an almost daily basis. The Plot Against America gives that world teeth and a purpose, imagining the random cruelties of anti-Semitism organised and directed.

18

After the historical panorama, a sparsely attended graveyard. Or a painfully righteous young man alone in his dorm room, tragically unaware of the small measure of time left to him. Or an actor, fallen from grace and shorn of his powers, contemplating his self-designed end in an isolated cabin.

Time has skipped, and I’ve jumbled the chronology, because, considerations of standard length doing the talking, shelving Everyman (2006), Indignation (2008) and The Humbling (2009) side by side might give you the heft and page length of a ‘standard’ novel, especially without the wide page spacing of a novel like Indignation (the copy by my left hand at least). Is it crass or meaningless to talk of binding and marketing? These novels are ill-regarded in Roth’s canon, and their shape, oddly enough, plays a part in this.

Really, it comes down to how much faith one places in the hackneyed critical term ‘minor’, which is too often, with writing, synonymous with ‘short’ or ‘not ambitious enough’, if your idea of an ambitious novel means a cast large enough for a soap opera. This is a species of literary criticism inexplicably tied up with marketing, with notions of saleability, size, drama. The novel of the times is always assumed to be enormous; it always covers a city and its populace. It never covers a living room. The servants of this particular species might not even find Thomas Bernhard sufficiently novelistic by their definition – too narrow, too manic, too psychologically implausible.

Back to that word: minor. Use it too often and the critic or reader can seem like Jeff Daniels’ insufferable failure in Noah Baumbach’s film The Squid and The Whale (2005), advising his son against reading A Tale of Two Cities (‘it’s minor Dickens’) and sending him safely into the comforting lap of received opinion.

That A Tale of Two Cities, or Everyman, or Franz Kafka’s Amerika (1927), or Vladimir Nabokov’s Transparent Things (1972), or Saul Bellow’s More Die of Heartbreak (1987) – make your own list – are lesser works from acknowledged greats is not up for debate. But only if the debate insists on compacting a varied and frequently contradictory body of work into the kind of single-serve statement that earns an author a solitary spot in a list of 1001 Books To Read Before You Die. Read any Henry James? If you’ve got the time, go for The Ambassadors, but if you’re up against it I’d start with Daisy Miller. Sure, you could read around a bit and get a richer and more complicated sense of the artist’s work, one that turns generalisations to dust and cheap quips about misogyny and egotism into echoes in an empty hall, but you’re only on holiday for a week and you’re probably only going to read one book anyway. Portnoy’s Complaint is over there.

19

So, Everyman – the unadorned tale of a sick man living a humbled life of no exceptional note. Never given a name by his creator, and hardly mourned by those gathered at his grave.

So, The Humbling – Simon Axler can no longer act, simply finds the old voice that spoke with confidence and assurance no longer there to use.

So, Indignation – Marcus Messner, away from inhibiting parents and alone at college, makes mistake after mistake. A single sexual infidelity that would fly past unnoticed in a Zuckerman novel brings his world falling down around him, and his religious convictions, or lack thereof, seal the deal. This is the terrain Roth came to chart in his last decade – characters who are fated to suffer. The characters in these short novels live in a cruel anti-terra of random sickness and likely doom.

These are books that deal with the kind of decent and non-hysterical (or hystericised) figures Roth in many ways left behind after the success of Portnoy’s Complaint, which ended forever the more mannered fictional worlds found in early novels such a Letting Go (1962) and When She Was Good (1967). The treatment of these earnest and decent figures still wrestles hard questions from their behaviour. Is their nobility alienating? Are they cowardly beneath their impressive fronts? Do they always act in the most responsible fashion despite their self-image? But Roth does so in a fashion that doesn’t make sport of the fundamental decency or plain humility all the same. This is not to suggest the Roth of the earlier novels was an amoral joker, but often the force of his rhetoric, the devil’s allowance he gave to his relentless monologues, frequently put decency in a corner and heckled it into resembling nothing more than deluded piety.

20

There’s a sense in these books of a whole world rigged to defeat young idealists and older professionals. In a different light, with a squint, it would be easy to find Indignation’s Marcus a somewhat grating young man – it’s hard not to imagine Roth at almost any other point in his career (other than perhaps at the very start) making some rich sport of him. But the character of Marcus is desperate and bottled and, finally, trapped. And Roth’s empathy, his unmocking attention, follows him down. When the story’s hook or ‘twist’ (as it were) is revealed, it functions as more than narrative trick; it is an inexorable logic righting its course and blithely handing out fate’s small reward. So many of these books, including Roth’s last, are portraits of lost youth in one form or another.

21

Regarding these short, death-haunted works: the necessary energy of fictional conjuring makes an equally pessimistic book – even arguably the darkest book Roth has written, Sabbath’s Theater – seem positively sprightly, if only because of the energy and bombast called to creative task. If the energy of Sabbath Theater’s roiling prose is the equivalent of a man trying to fuck his way past the necessity of suicide, something like The Humbling, with its character in a state of far less frenetic malaise, is an unadorned picture of loss. It’s a fitting style if nothing else. That these books are rarely considered as Roth’s best is unfair – all three contain passages of great beauty, or feeling, or dark humour, Everyman in particular.

22

A curious thing to write: Exit Ghost (2007) feels like the only Philip Roth novel that didn’t need to be a novel. It seems piecemeal, full of occasional highlights and much clunky writing. It also feels like the act of finalising business that was already well and truly settled. We return to the inscrutable reclusive novelist E.I Lonoff, central character in Roth’s earlier The Ghost Writer (1979), and to the warring mysteries of both the private and the creative life. Thrown into the mix are Roth’s take on the 2004 election and some standard Roth sex talk done without Sabbath Theater’s fire or The Dying Animal’s gravitas – what we are left with is curious and underwhelming indeed, and all the more regrettable as it is the last outing of Nathan Zuckerman.

A serious problem with the book can be seen in the book’s obvious highpoint: the long section near the end where Zuckerman, in a tribute to the recently deceased George Plimpton, rails against the war on the privacy of writers and considers the subtle connections between biography and creation. It could almost be an essay, and when I first read the novel, I wondered why Roth hadn’t simply written one, allowing himself to address these issues without the unwieldy framework of a novel. Thinly plotted as Exit Ghost is, it grinds to a halt during these pages, almost wandering in without any preparation at all. It feels hurried, filled with concerns not worth the shape of fiction. Any Roth fan would want to read his take on George W. Bush’s re-election, but the material never comes into focus in Exit Ghost. It remains a home for patches of writing waiting to be rescued from a muddled form.

23

But what if you only wish to write novels, to make them the home of your concerns, however fleeting? Is the description of a political scene and the feelings of those gathered around the TV on election more relevant in a book stymied by the slow time of editing and publication than on a barely-read blog? Is a testament to George Plimpton lost sooner on the pages of the New Yorker than contained in the pages of any novel, a surer shot at some measure of immortality?

24

The treatment of illness in Nemesis is tender, petrified, and alert. There is none of The Anatomy Lesson’s hysterical hypersickness. There is a voice in the dark instead of an insistent megaphone, barking to keep its attention held. The novel skirts sentimentality in the way it approaches fundamentals that might pass as despairing and well-intentioned juvenilia in the hands of another writer, but which, in Roth’s hands, feel like agonised cries that have suffered 50 years of bad weather. What is the logic of illness? Why him and not me? Why the young, ever? Can there be any rationale for the suffering of the young? And what does my fear in these moments truly say about me? That Roth’s last novel (whether he knew it would be at the time or not) doubles back around to these fundamentally unanswerable questions is chastening, a quiet admission of confused fear – perpetual fear – still ruling the lives of Roth’s Newark.

Nemesis, like The Plot Against America, is a vision of childhood where everything that can go wrong does go wrong. In its depiction of a polio epidemic slowly infecting a town’s youth, it plays like a stern but ignored warning from a parent about playground safety turned tragic. The Plot Against America took the given bigotry of the era and let it have its hypothetical way with the country; Nemesis gives the reader an epidemic without a source, and a baffled population ready to assign blame. Once more Roth places a fundamentally decent and honorable figure at the centre of his book and, without irony or exaggeration, shows us how he is undone.

25

In the second Zuckerman trilogy – the American trilogy – seemingly simple encounters, or stories that might seem simple at first, expand into unmanageably complicated and contradictory tales that rob the initial encounter of all its easy assumptions. A professor is accused of racism, but is shown to be anything but racist. A seemingly affable and banal man’s pleasant conversation hides a life of trauma.

In Nemesis, that encounter is left to the end; the narrative order of ‘discovery and deepening’ is reversed, with everyone left in loss. Where the novels in the American trilogy open out, Roth’s subsequent novels fold in on their protagonists.

Nemesis indulges in a small piece of narrative legerdemain that pays off at the book’s end, but its final chapter is infused with genuine melancholy and pessimism. It is peopled by characters who find themselves diminished by time. They are struck down by the furies. They are the final cast of characters in a fictional world that, in its last decade, rarely let in light without revealing the danger awaiting them and us.

Taken together, Roth’s last novels are plots against nostalgia.