I went to university on a $10,000-a-year scholarship, more money than I'd ever had before. I was told it was for academic merit, but their motivation in admitting me was obviously to tempt another bequest out of my father, who had already paid for a big building on campus, a steel and glass obelisk called the Hurley Institute for the Advancement of Minerals Research. I went there once for a tutorial. The air-conditioning was up way too high, it raised goosebumps on my arms, and there was a huge lump of iron ore on display in a glass case in the lobby.

Through a Glass, Darkly

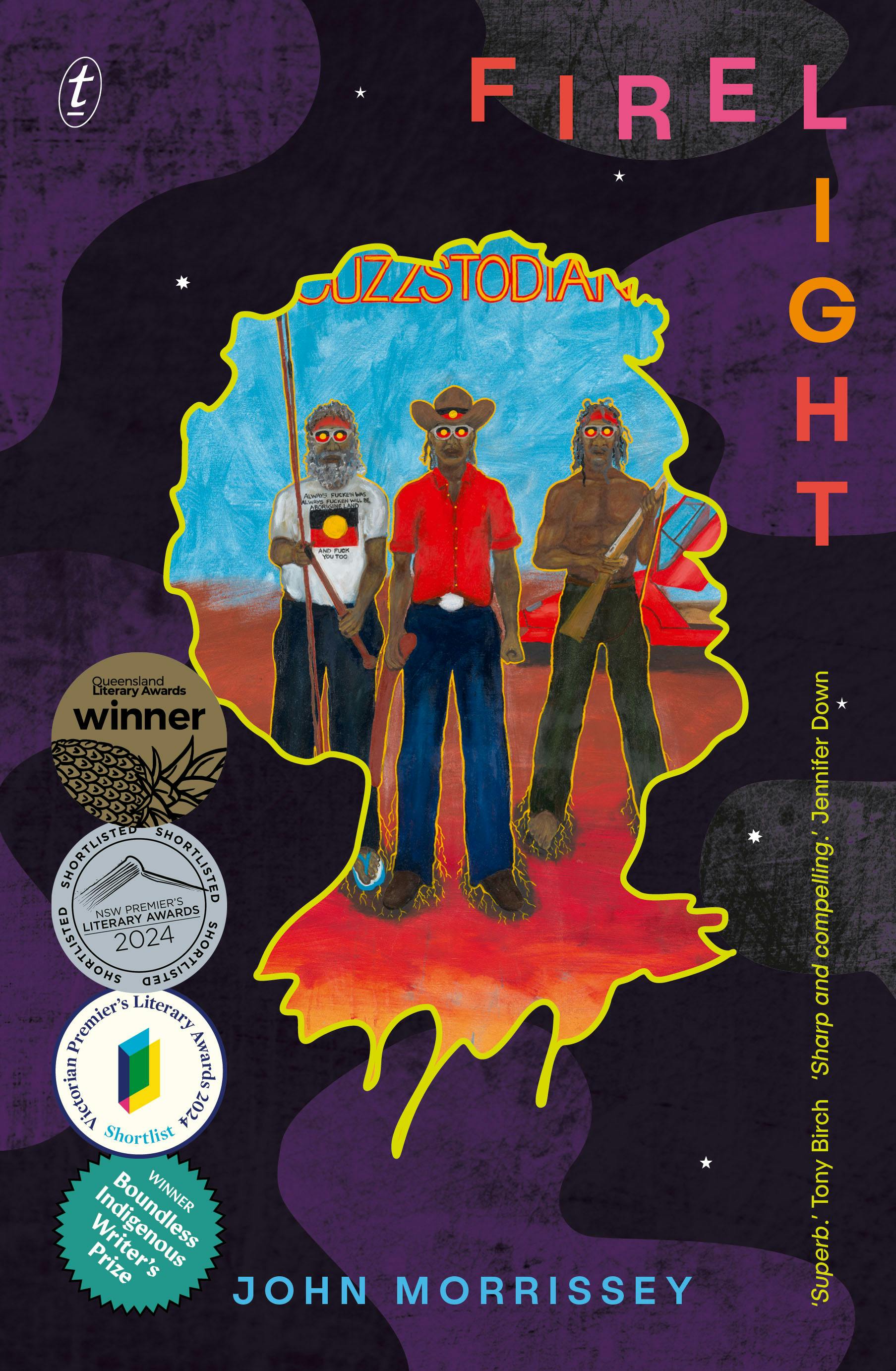

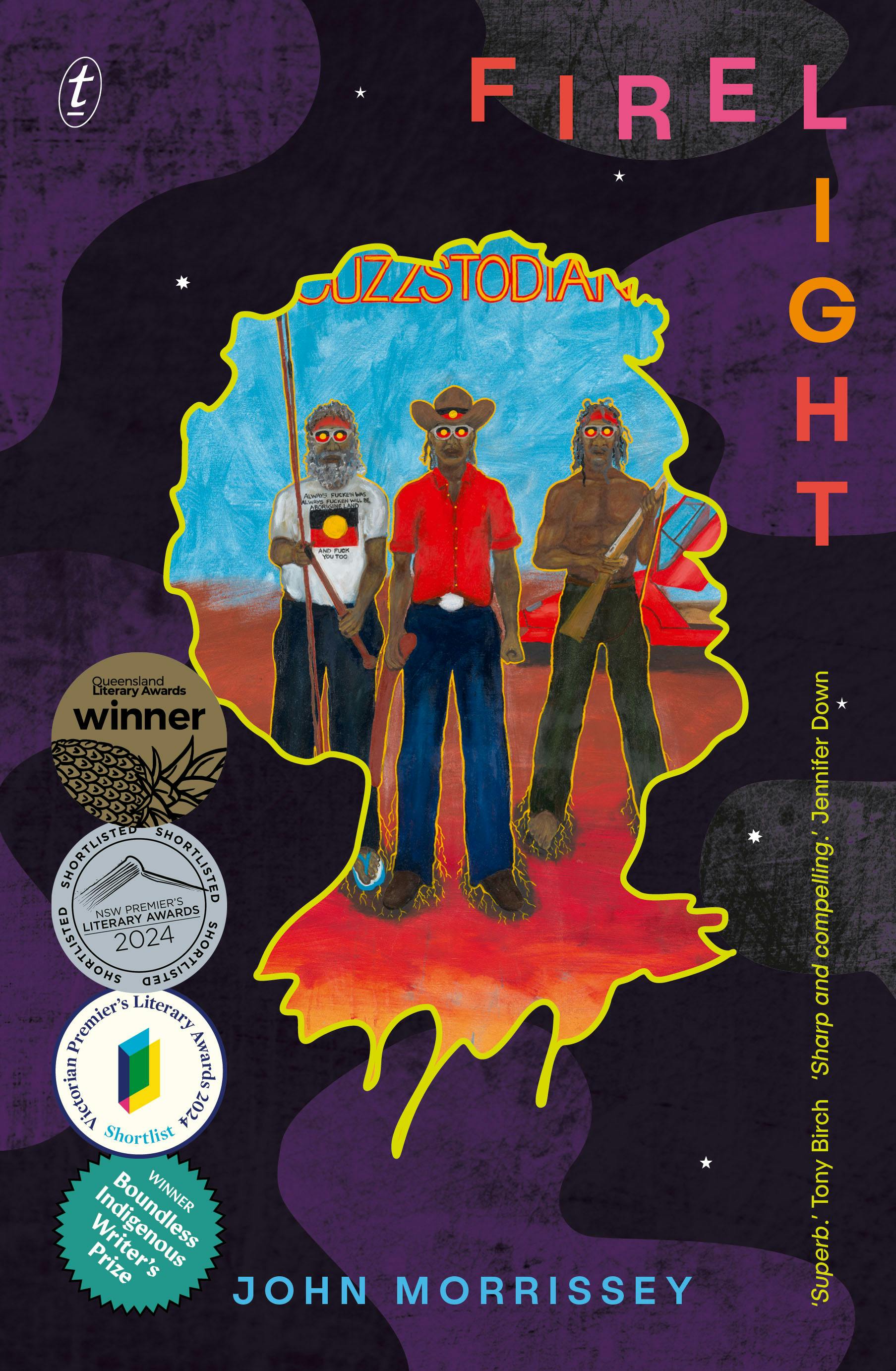

Mykaela Saunders on John Morrissey’s speculative fiction

Reviewing John Morrissey’s collection of short stories, Mykaela Saunders shows how the author’s flexible use of speculative fiction suspends the reader between allegorical explorations of colonisation and an investment in the weird and beautiful.

I try not to get too excited about books anymore. The hype is rarely deserved, and I’ve become so bitter and critical, especially about some of my own people’s writing. I’m not sure what I’ve come to hate more: ‘important Aboriginal writing’ that is painfully, obviously written to teach white people a lesson, or ‘important Aboriginal writing’ that has nothing to do with us at all – so much so it could have been written by a white person. Maybe I hate both equally.

Still, I’ve been anticipating Kalkadoon writer John Morrissey’s debut short-fiction collection Firelight for a few years now. I first read the opening story ‘Five Minutes’ in 2021 after I emailed John on my quest to solicit submissions for This All Come Back Now, the blackfella spec-fic anthology I was editing. I sought him out as his work had pinged on my radar twice before that, both times as a contender for Overland’s Nakata Brophy Prize in 2017 (shortlist) and 2018 (runner up); I had vaguely remembered that the judges’ citations described his stories in speculative and gothic terms.

Firelight is even better and weirder than I could have imagined, and easily escapes both of the problems I mentioned earlier, clearing the low bar of decent black writing by a long way. The writing is elegant, the humour dry and subtle, the ideas fresh and absurd – this all makes for an exciting book, in which many speculative genres are present: Firelight uses themes and tropes long associated with horror, science fiction, ghost story and the gothic, as well as traditional fairytale and fable. But it’s a book that has cross-over appeal for both genre and literary audiences, as shown by its winning the 2023 Aurealis Award for Best Collection as well as the 2024 Steele Rudd Award for a Short Story Collection at the Queensland Literary Awards.

In this review, I want to consider, perhaps inevitably as an Aboriginal reader reviewing an Aboriginal book, how we can see Australia clearly, albeit darkly through these stories, even if John himself is only glancing at race relations, or looking at the colony askance. In the penultimate story ‘The Last Penny’, Amy takes down all the photos of her deceased, violent father in his house; ‘I didn’t want to see myself darkly in the glass,’ she reasons, not wanting to see him reflected in herself. (A similar phrase was used in a previous publication of the opening story ‘Five Minutes’, which is how it hooked my attention.) I welcome stories that look at this colony with hard, unforgiving eyes, and speculative fiction can make this an interesting and novel exercise by scrying its crimes through shadowy reflections. I want to focus on Firelight’s use of allegory to achieve this, and allegory’s relation to, and departure from, analogy – by examining first how allegory and analogy work (or don’t) when talking about ourselves, and then to what ends Aboriginal spec fic writers are using these.

Whenever we read (or write) a story as an analogy of something else, the task of figuring out the connections between tenor and vehicle tends to upstage our enjoyment of the story on its own terms. It might initially feel clever to marry up this plot point to that real thing in history, or this character to that real person, but these stories rarely tell us anything new or interesting about ourselves as a people – which is one important reason I study First Nations speculative fiction. Rather these stories are often attempts to teach white people how it feels to be us. A dubious goal, and probably a waste of time.

Not all Aboriginal stories have to be analogous to racial or cultural experience, something I want to take on board for my own over-exposed first drafts. Sometimes, or preferably more often, our stories can be weird and gorgeous just because. Still, read closely enough, all of the stories in Firelight do say something about the Australian colony’s past, present, and future. But it's never obvious exactly what they’re trying to say, or if indeed there are any special or hidden messages. This is one of the strengths of the book’s allegorical mode.

I also want to highlight two of the interesting structural tricks that John pulls off. First, in most of the stories, a protagonist’s uncontrollable inner life gnashes at the flesh of their boring real life, sometimes eating it up entire. John, a public servant by day, has a sharp sense of how the imagination can colour the doldrums of the outer world, through twinning, mirroring, echoing, layering, and dichotomies. Secondly, he is a master of the escalating short story structure where some threads knot up while other knots unravel, and the stakes climb ever higher, blossoming into a satisfying and often subtle ending, or landing on stunning, awe-inducing imagery – a stampede of megafauna, for instance, or a monstrous thylacine pup.

‘Autoc’, ‘The Rupture’ and ‘Special Economic Zone’ are all examples of Indigenous Futurism, a term coined by Grace L. Dillon in 2003. Just as Dillon had theorised the genre in her edited collection Walking the Clouds: an anthology of Indigenous science fiction (2012), these three stories toy with linear temporality as a way to talk about all times and how they are woven together.

‘Autoc’ is an accomplished science-fiction novella, both surreal and atmospheric, and a bold experiment in genre and allegory. Let’s start with some ancient history from this world: a native primitive society is visited by a missionary from a technologically advanced society. He treats with them to ‘share’ their fertile land and fresh air with his own people; all he has to offer in return is the power of his deathless God. Sound familiar? Well, don’t get too comfy, because it’s not possible to map the plot exactly onto our territory. The beauty of this story is that just when you think you’ve worked out who is standing in for whom, some detail throws you off, forcing you to rethink the entire analogy you’ve made up in your mind and thus to read the story differently. This is how ‘Autoc’ stays fresh; although it seems like a parallel of our colonisation, it resists neat equivalence at the same time, freeing itself from a predetermined narrative fate, and making other attempts at this kind of story seem heavy-handed and lacking in imagination.

All times are compressed and nested within the world of ‘Autoc’, and so it is cleverly layered in the story, too. On that planet – just as here on Earth – the past isn’t dead but permeates all stories onward, with founding myths and first contacts reverberating through all the coming ages. Both the fictive planet and its real counterpart are multiply haunted by their pasts and futures.

First, the story’s past: some 500 years before, predecessors of the current society colonised the planet and seemingly wiped out the indigenous Autocs, though Autoc lore and legends pervade the present through settler occultists who trade in these wisdoms in pamphlet form. Present day anthropologists and academics have created a small but solid body of literature about the Autocs. But the mysteries of history endure: the experts are in stark disagreement with each other, even to the point of debating whether the Autocs even existed. The cult that arose around the wisdom of the Autocs mostly cobbled their lore together from the thesis of a now elderly disabled academic, whose prophecies even successfully predict the moon’s attack. With their arcane rituals and symbolism of blood, these cultists read like the type of northern rivers New Agers who dream of Aboriginal spirit guides and race shift into Aboriginal themselves upon waking. They are true believers, fanatical in their self-appointed exceptionalism and authority.

John has rendered the ancient Autoc mythologies alluring to the cultists and to the reader by including excerpts of the mysterious pamphlets in the story. These range from an account of the Autocs’s first contact with the missionary; to their riddle-like prophecies (including the dream of the two storms – one of ‘great pieces of stone falling and covering the surface of the earth’ and the other of ‘fire mounting up to the sky’ – that has big implications for the story’s ending); to references to the Green Man, a mysterious entity who appears responsible for the death of a small boy in the first part of the story and inhabits the dreams of the boy’s neighbour, Shah (who might be an Autoc descendant); to mentions of the planet’s great demon creatures – angel-animals that were worshipped by the Autocs and remain hungry for sacrifice in the current world, despite the annihilation of their stewards. These latter entities reflect places of power and sacred story on our continent that will always exist, whether we are colonised or not. As in Australian literature’s earliest stories, the trope of the lost settler child and the menacing native is part of the nationalist paranoia of this hot, martial planet too, which is also gasping through the death throes of its own late empire.

This planet is populated by descendants of paranoid hyper-militant settler-colonisers, and in the grand tradition of confecting terra nullius to assuage their own existence on stolen land, it is also haunted by its future. A colonised moon hovers in the sky; an ever-growing belt of buildings expands across its surface over the decades of the story. This may be a reference to Ursula K Le Guin’s novel The Dispossessed (1974), where two populated planets Anarres and Urras orbit each other, and the inhabitants on each planet condescendingly refer to the other as ‘the moon’ (‘Where, then, is Truth?’ asks one of the teenage boys on Anarres, as they philosophise about this; ‘In the hill one happens to be sitting on’, answers his friend). But where The Dispossessed follows one Annarren scientist’s attempt at making peaceful contact with the Urraen civilisation, the citizens in ‘Autoc’ can only imagine war.

As a nod to Australia Day, the settler-colonial society in ‘Autoc’ celebrates Landfall Day, which is likewise celebrated on the first day of native apocalypse. The proceedings are a vulgar display of military power, celebrations which also double as preparation for when the enemy Moon people might attack. This possibility is a topic of political debate and source of social divide. The planet’s analogue of Fortress Australia wins out, and public funding is poured into battle enforcements with the intention of protecting the population, though one of these proves dangerous for Shah’s young neighbour as it becomes the site of his disappearance. The nervous and paranoid racism of this planet is all too familiar, and John writes it with subtlety and restraint. It also becomes self-fulfilling prophecy; at the story’s close there are ‘silver flashes flickering across the surface of the moon’ and ‘massed threads of silver light as fine as spiderweb [...] emerging from the moon’s north and south poles and curving gently, irresistibly towards the planet’ – an image so brilliantly poised between beauty and threat that it shakes the reader out of their analogy-spotting.

One important character in ‘Autoc’ is a plant, the native kalyma, which grows fast and dense and cannot be controlled by slashing and burning: ‘the kalyma could only be killed by excavating the soil entirely’. In the allegory of Aboriginal/Autoc existence, it becomes a symbol of resistance, something explored by Wiradjuri poet Jeanine Leane in her poem ‘native grasses’: ‘try to kill them off spread poison / pull them out by their roots…if you let them grow / they spread like wildfire all over the country’. At the story’s close, when Shah feels drawn to ‘continue her wandering among the kalyma’, she finds her brother, who has taken the Green Man’s heart and become him: ‘[his] skin was the green of a leaf held up to the sun, and his legs disintegrated at the ankle into hanging brown roots’. Perhaps this alludes to the way our cultures are cannibalised by outsiders. Or perhaps not.

In ‘The Rupture’, humans play God with science, and a miracle happens at the crossroads of life and death. The protagonist Caroline is caring, warm, and sentimental in contrast with the cold bureaucracy of the science corporation she works for, which is overseen by a boss made of the same heartless substance. This contrast further reverberates throughout the story in the binaries of science and intuition, touch and sterility, and nature and technology.

In the story’s future, a private lab funded by a mysterious benefactor is making its umpteenth attempt to bring the thylacine species back to life. Artemis, the dog tasked with incubating the experimental thylacine embryo, is named after the Greek goddess of wild animals and childbirth. She is treated as a uterus on four legs, a Frankensteinian incubator, poked and prodded with gloved fingers that make her shiver; any attempt at care and connection with her is curtailed by management, whose science seems stuck in 1936 when the last real-world thylacine died. So starving this pregnant creature of warmth, light, and affection, it’s little wonder that their experiments so far have only proven abortive.

As with other stories in Firelight where inner and outer worlds bleed into one another, Caroline’s guilt for Artemis feeds into her recurring dreams where she floats in a dark womb kept rhythmic by a distant heartbeat. She has a strong psychic connection to the embryonic, experimental thylacine too, dreaming of it at the exact time it is born in the real world. In this particular dream, as they inhabit the womb together, the embryonic thylacine tells her that it won’t be coming back, but it will make way for something else. And it does. What is born is not what was intended by the lab, but a self-replicating version of the ancestral thylacine, split down the middle, more terrible and strange than anything the scientists might have intended, or even imagined. The story ends with the scientists ‘gathered around the incubator, frozen in positions of adoration’, in a scene invoking worship and rapture.

This story is set in Hobart in 2038, 250 years after British invasion of our continent. To commemorate the semiquincentennial, the colony plan on doing ‘a parody landing of the First Fleet’ with an unnamed ‘comedian’; I can’t help imagining someone like Tim Minchin. But given the deep cultural cringe of the Australian colony, how different would this really be to a serious reenactment? Is the story’s future Australia finally, truly postcolonial enough that it can satirise the blatant cheekiness of the First Fleet’s invasion of 1788 and the subsequent ultimate piss-take – that is, staying put and laying claim to our already owned and occupied lands?

For comparison, let’s consider the farce of real-world Australia’s sesquincentennial reenactment, where the colony surely broke some human rights conventions in celebrating its own amazingness. Sydney blackfellas refused to take part in the 1938 spectacle, so the organisers coaxed blackfellas from Menindee and Brewarrina in western New South Wales to come to recreate the First Fleet landing. The Menindee and Brewarrina mob were held overnight in the Redfern police barracks like criminals. Local mob and other blackfellas who were in town for the Day of Mourning protest tried to visit them, but were denied by the Protector of Aborigines and the Police Commissioner, perhaps to curtail the possibility of the city blacks encouraging the bush blacks to boycott. At the reenactment, the Menindee and Brewarrina actors were made to flee in fear from the conquering whites; ochre from elsewhere was painted on bodies from elsewhere, while local descendants of those first invaded watched on from the sidelines.

The last thylacine died only two years prior to this reenactment – over 100 years before ‘The Rupture’ is set – in a concrete cell watched by onlookers. The species was written out of existence through a combination of anthropocentric climate change, hunting, and competition from dingoes and dogs, with human encroachment finishing off the job. It’s fitting that its image is emblazoned on the Tasmanian coat of arms as it is both a symptom and herald of colonial apocalypse.

In this story, Artemis is confined to a cell, just as the last real thylacine was, and just as those Menindee and Brewarrina mob were too – as well as way too many of our people are right now. The scientists of the story believe they are reviving the dead and giving life, but they are creating monstrosity. If the thylacine died out because its world ended, something new must come forth for this new world: the now of the story is the time of monsters.

‘Special Economic Zone’ is set in a not-too-distant future, in a world built layer-by-layer upon the horrors of our own, resulting in an uncanny dystopian satire. To wit: a few years ago on my lunch break, I visited Mackay Regional Botanical Gardens. I’d been researching examples of Yuwibara genocide and ecocide in the area. Fastened to a rock wall, child-friendly diagrams valorised the extraction of fossil fuels. This only made sense in light of the nearby plaque announcing that that section of the walk was sponsored by Big Coal. ‘Special Economic Zone’ opens in a similar way, in a far hotter world:

The protagonist Emma never knew her father, an iron mining magnate whose stature and money never provided for her. When he dies, Emma is given instructions that set her off on a quest for her inheritance. The story has a fairy tale structure, where a poor child is revealed to be of noble birth, and is given a key to open a lock that will reveal her rightful treasure. Of course, the promise turns out to be empty; Emma has been bequeathed a self-aggrandising note and a lump of iron ore, reminiscent of the lumps of coal given to naughty children by Santa. The note means nothing to the daughter and the ore only angers her; while it might have once had some monetary value, it’s worth almost nothing now that its price has plummeted in this climate-changed world. In fairy tales like this, the mother is often done away with too so the orphan child can learn of, and come to terms with, their legacy. It’s not clear how Emma’s mum died, only that she was young and she was often angry at her dad.

A lot of what is going on in this world is extrapolated from our own. With the same name as the killer cop from Palm Island, Emma’s father Hurley is also the absent father of many wayward kids – just like Lang Hancock who also made a fortune mining Aboriginal land (and also had an unacknowledged Aboriginal daughter). As patriarch of his company, Hurley is also reminiscent of Succession’s Logan Roy, likewise a titan of industry and a terrible dad. Reconciling the conflicts between industry and family is never a priority for such men. And as Adani intends, Hurley carved the largest open pit mine in the southern hemisphere, so big it can be seen from space. He also made paternalistic policies for all the poors in his kingdom, the titular ‘Special Economic Zone’, and there are many parallels to proscribed areas of Australia, such as those Northern Territory communities subjugated under the Intervention. Porn, alcohol, and guns are banned in the Special Economic Zone, and the poors are also allocated the Essentials card – analogous to Australia’s Basics Card – which citizens must use in lieu of money. This controls how and where they spend their meagre incomes, forcing them to purchase groceries at jacked-up prices rather than cheap or pleasurable things. Back in Brisbane, Emma lives in a housing complex run like a reformatory, where curfews and other rules are enforced by punishment, which leads to more disadvantage – again, echoing the way Aboriginal people are controlled. The world of this story feels the most cartoonish of the collection; using similar methods to Alexis Wright in her dystopian world of The Swan Book, John distorts features of our world so far that it becomes nightmarish caricature – and a clear way of seeing the violence of bureaucracy.

The next two stories I want to discuss, ‘Five Minutes’ and ‘Ivy’, are examples of weird fiction, a term reserved for those speculative stories that are rooted in cosmic horror and skim across other, non-realist genres without being beholden to their conventions. And just like the flawed protagonists of weird exemplar Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach tetralogy, the rich interiority of the protagonists of ‘Five Minutes’ and ‘Ivy’ holds just as much narrative weight as the stories’ immediate external action. Each story echoes the other too in terms of character and plot: both protagonists are reclusive young men whose rich inner lives eventually take over their social realities. These antisocial weirdos are preoccupied with health and hygiene; they both avoid their parents; and both have unattainable romantic interests, perhaps reflecting the racial anxieties of black men dating white girls who are perceived to be above their station.

‘Five Minutes’ is hyper-conscious of genre and structure, and plays with both through its two layers of reality: the primary story concerns Mikey, a misanthropic public servant who writes sci fi (or, rather, mostly thinks about writing it), and the other takes place within the cosmic horror story he’s imagining – of insectoid aliens coming to annihilate humanity – which then starts to take over his waking life. The ‘five minutes’ of the title refers to the extra time on earth the aliens agree to give blackfellas – as acknowledgement of our long, peace-loving existence – after they extinguish the rest of humanity from the planet. When that time is up, our people are not killed, but abducted together and placed into a life-sized diorama, complete with lost megafauna.

Mikey is an accurate rendering of what it’s like to be black and creative in a white and normal workplace, where one has to pretend and perform for their pay, particularly when we already feel like outsiders among those of our own people who strive towards middle-class mediocrity. This story is an affirmation for blackfellas who work in vast bureaucracies under white bosses with no sense of humour, who control every pull of the purse strings of Indigenous funding and budget for projects in the shallowest and most cherry-picking of ways. Mikey would resonate with any nasty little daydreamer who’s been forced to socialise with colleagues you have nothing in common with, particularly if it involves alcohol; who’s far too loose and mean-spirited after a few drinks to socialise safely, always taking so much care to never reveal anything of your upbringing or the mischief you get up to on the weekend, knowing you’ll get fired otherwise, so you must always pretend to be like these people. Mikey’s solution is ostensibly to ‘drink steadily and try not to pay attention’ to anyone. Yet he laughs when he learns his boss’s dog is taken by an eagle, and he explains his reaction badly, putting his foot in it deeper still. I’ve read this story dozens of times by now and never fail to giggle along at this point. I’ll probably do so until my dying day. Maybe I identify too strongly with Mikey, especially as I first read it at a time my neighbours, AirBnb feudal lords, got a small yappy dog that they’ve still never bothered to train out of barking at everything.

‘Five Minutes’ is a story mostly about stifled creativity, I think. How many of us, like Mikey, have some idea of ourselves as creative types when all we do is talk instead of actually working and producing anything worthwhile? And when you do squeeze the occasional nugget out (in the rare time available when work or drinking or hangovers haven’t vampired all of your creative juices), it’s never as good as you wish it could be. The art never matches the vision. And that’s because you don’t get to practice and hone your skills enough. Don’t we all know about the way that repressed fantasies with no healthy outlets bleed into waking life and take over as though they have a life of their own (because they do)? This takes on literal force when Mikey leans in to kiss his coworker, and one of his imagined aliens emerges from her mouth and studies him:

With infinite care I lower my mouth towards hers as her lips part wider. Something stirs within her mouth. A twinge of unease travels through me. My unease turns to fascination and I watch, transfixed, as something long and dark emerges from between her lips and undulates towards me. A centipede has taken root in place of her tongue. Its tiny legs are twitching wildly, as if seeking to find purchase on the air. It draws nearer until it is inches from my face; I can look directly into its compound eyes, and see the venom gleaming on its fangs. Jane's expression is dull and amiable. The centipede could attack me if it wished – could blind me with its venom. Why does it refrain? What is the nature of our understanding?

Like Bluebeard’s dead wives rattling in the cupboard, their blood staining the key to their freedom, or like childhood monsters under the bed, or those we fantasise about coming for us in spaceships as adults, the centipede becomes an emblem of the stories that live inside us and are screaming to get out, and they will come out one way or another – ideally through a dedicated, intentional creative practise, teased out with care and devotion, rather than eroding their way into banal situations, and sabotaging all that stands in the way of their full realisation.

While Mikey earns a salary and is preoccupied with aliens, the insomniac protagonist of ‘Ivy’ is broke and unemployed, and slowly merges his consciousness with the creeping plant of the title. He too creeps around, stalking people at a distance, and only experiences genuine peace lying rooted to the earth with his eyes to the sky. As above so below, soon ivy is all that makes sense. Its fractal logic is symbolised by the tessellating vegetal patterns of the vine. He feels the plant as its spirit seems to flower and grow within him, and he also sees it everywhere without: ‘Often he was surprised by his own image in the glass doors that led from the kitchen to the garden. Behind his reflection he could see dark foliage and swollen, ghostly-white flowers.’ Like the kalyma in ‘Autoc’, the ivy has a real but alien autonomy, ‘straining and growing, as if it had adapted, like him, to feed on moonlight’.

Various subtle dichotomies are woven through this story: what is felt competes with what is seen; the ivy’s softness is contrasted with hard iron; the nocturnal protagonist and his diurnal mother pass like ships in the night; and natural moonlight is weak and watery compared to both the football field’s searing floodlights and the powerful searchlight of the panopticon, the protagonist’s ideal throne in his visions:

He dreamed he was sitting in a narrow chair – cruel to his spine – at the top of a tall guard tower. The chair and the struts of the tower were made of iron. The chair was fixed to a swivelling platform.

At first the images of the tower and its searchlight seem strong against the ivy, but in the end, it is the latter that prevails, ‘pull[ing] down and devour[ing]’ the iron structure.

The story’s protagonist is a version of Fight Club’s Tyler Durden, particularly in the way both characters are members of mysterious men’s groups that are fixated on violence and adhere to strict lifestyle rules while ostensibly abhorring degeneracy. Over Zoom, the protagonist reports to the mysterious Tom, the leader of a group trying to recruit and prepare him for their imminent first real-life meet-up. The group is a kind of secret male society training for some end-time scenario; Tom intends them to be soldiers. Are they incels? Is this a race war? Tom calls the protagonist’s situation with the rich Sophia ‘miscegenation’, a word loaded with such a specific history and charge that it glows like a dark light in this strange story.

There are similar real-world cults led by predators that recruit young men, children even, grooming them online with similar ideologies of race and gender. Some of the more nefarious groups have blood on their hands. One of my old housemates, Black Metal Jacque, was once part of a milder group like this, though to their credit they were at least multicultural and not, to my knowledge, fixated on sex. His fellow survivalist parkour practitioners were obsessed with the apocalypse and traded in tips for surviving any given end-of-the-world scenario, relying solely on their own wits and bodies. It turns out they were all isolated and lonely, mostly neurodiverse and ripe for the picking; many of the members were heavy weed smokers and I suspect some of them were on the pipe too. Between fantasies and fears for the future, it’s little wonder they all fancied themselves as soon-to-be lone wolf heroes of an imminent apocalyptic societal collapse.

The fictional counterparts of these loners – the protagonist of ‘Ivy’, Durden, and Mikey from ‘Five Minutes’ – are all nihilists who suffer from repression and split personalities; they have unconventional romances (or lopsided infatuations, depending on who’s asking), and experience such extreme mental instability that they can’t keep their actions and fantasies totally straight. In the collision between their inner and outer worlds, John shows the power that lurks beneath the surface of all people.

The two final stories in Firelight, ‘The Last Penny’ and ‘Tommy Norli’, are Morrisey’s improvisations on the gothic genre – a genre perfect for us as wronged people on brutalised land. ‘The Last Penny’, ostensibly a ghost story, is a harrowing read – though not for its speculative elements. Paedophile priest Stephen writes in his diary that his sister Amy is one of the few people who will understand him, possibly because they grew up together under an abusive father, though there’s a lot that’s only implied. Despite Stephen’s belief, the story examines Amy’s anger and refusal to forgive her brother for his crimes. At their father’s poorly-attended funeral, the only one who truly mourns him is his brother, their uncle, who ‘cried freely and generously, the only one to do so’. This sibling dynamic suggests that it’s only those who grow up in the same conditions who can ever truly understand each other, no matter how different they end up turning out. Stephen banks on this understanding while Amy rejects it.

From Stephen’s childhood baptism of his Aboriginal neighbour, whom he sees as a Magical Koorie offsetting his own colonial gold-panner persona, to his adulthood as a missionary converting the heathens of the Third World, he appears to have always had a taste for lording it over brown and young people, groups infantilised by the church and by himself – a relationship taken to its most heinous logical conclusion in his paedophilia.

Despite John’s ability to render these complex moral dynamics with maturity and restraint, ‘The Last Penny’ felt like the least realised story of this collection. It is a grim, realist story right until the end, where Amy encounters a girl ghost and the burnt apparition of her brother. These devices feel very sudden and unearned, and I had more questions than answers at the story’s close. Is the part where Amy sees the girl ghost and her brother a vision, or are they supposed to be real entities? Either way, ghosts usually represent a character’s guilt or rage, so why does the ghost appear to Amy, who wasn’t a paedophile? Even if we suspend disbelief and read the ghost as an amalgam of all the victims of that special paedo unit at Stephen’s jail, how then did this ghost get the last letter he had written to his sister and sent to their neighbour previously? This scene didn’t really make sense, and it stands out because all of the other weird and surreal stories in Firelight do make their own kind of sense. The blurring of realities between the material and immaterial worlds in ‘Five Minutes’, ‘Ivy’, and ‘Autoc’ is seamless throughout, ramping up gradually from the very start of the stories and making complete sense within the logic of their respective worlds. There is nothing of the ghost or horror story for most of ‘The Last Penny’ and so the late-addition speculative elements, while striking and horrific devices, feel unresolved.

The closing story, ‘Tommy Norli’, on the other hand works brilliantly as gothic, where trespassers, both settlers and blackfellas alike, live in fear of the land and the menacing natives that belong to it, and whose violent deeds torment them thereafter. This story was told to John by his father, and presumably originates from the Kalkadoon community. Tommy Norli is born to a black mother and absent white father on a north Queensland station where he grows up and later works, before leaving to travel with a new white boss. One night on the road, deep in some other blackfella’s country, the pair hear a song of warning emanating from the bush and suddenly a warrior comes out of the darkness and attacks Tommy’s boss. Tommy kills the warrior, and then he and his boss tie the warrior’s body to the nearby mangroves. The song that comes from the bush has now turned to one of mourning, and Tommy envisions black hands coming for him from the darkness. He and the boss soon part ways, with Tommy making his way back to the station, resuming his old job, and starting a family. He remains haunted by his deed, and watchful too, especially when he hears news of his old boss’s unfortunate death, which he knows to be the work of those black hands that once tormented him. As allegory and as gothic, ‘Tommy Norli’ reminds us that colonial violence entangles us all as its effects reverberate across time and space, through land and people, and nobody gets to pretend otherwise.

Throughout Firelight, as rumination struggles for supremacy over action, and as imaginations play havoc with reality, the stories coalesce in images that vibrate and glow with dark magic from John’s mind. Each of these stories looks at the colony’s past, present and future in different ways, using devices associated with weird, science, climate, horror and dystopian fiction genres, as well as satire and allegory, while evading capture by any one genre. Part wish fulfilment and part nightmare, Firelight offers grim and lucid ways of seeing this colony through all times.