I am a Wiradjuri Man!

I live on the Murrumbidgee River, where life’s free & the best

of place, all around!!

I live of fish that I Catch, & travel into town every Couple

of days for our Supplies.

While at night when the Stars are bright around Our fire at night,

the laughs and yarns that we have, ill never forget

Once ive had enough I grab my Rod and Wonder off On my

River!!

Dreaming Inside-out

Luke Patterson on Dreaming Inside Volume 10

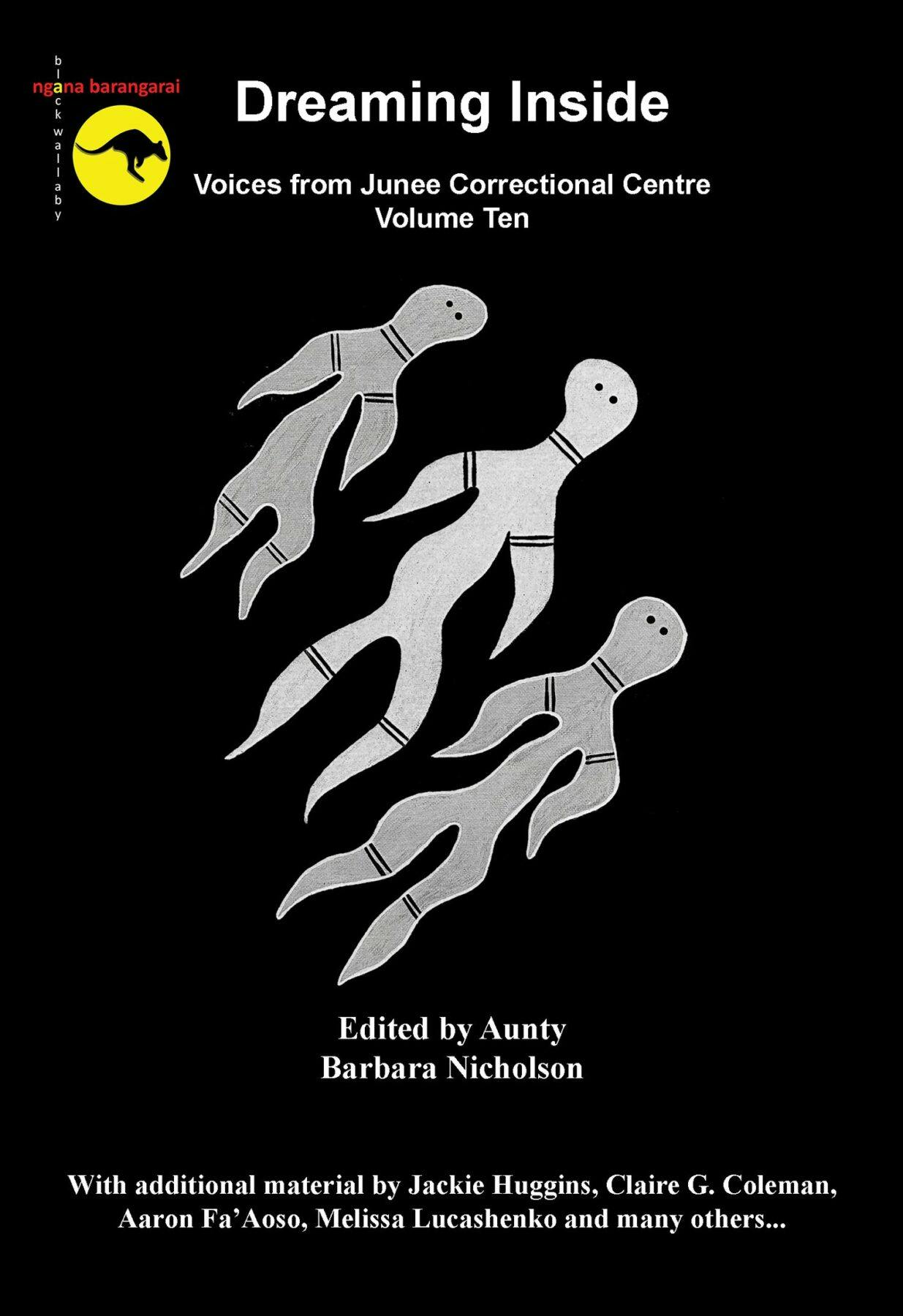

Dreaming Inside: Voices from Junee Correctional Centre is an important anthology of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander inmate poetry, art and storytelling. Now in its twelfth year and tenth volume, over two hundred First Nations authors have shared their stories, songs and critical reflections to a general reading public, not only enlightening ‘outsiders’ about the conditions and contexts of Indigenous incarceration but also significantly contributing to the canon of Indigenous writing.

In 2012, with support of South Coast Writers Centre, the project was originally conceived as a one-off workshop to be delivered by Wadi Wadi woman Aunty Barbara Nicholson while accompanied by Bruce Pascoe, John Muk Muk Burke and Simon Luckhurst. So inspired by the work produced, the group decided to bring the writing together in a single published collection to which inmates gave the name: Dreaming Inside. In a last-minute moment of foresight, before going to print, Aunty Barb added ‘Volume 1’ to the front cover, foreshadowing the ongoing significance of the anthology.

Since this beginning Aunt has led a rotating lineup of Indigenous and non-Indigenous authors, actors, musicians, lawyers, criminologists, health workers and other willing participants toward Junee, as a part of her Ngana Barangarai (Black Wallaby) writers team. I’m fortunate to have taken that journey with her three times now. ‘Fortunate’ isn’t exactly the word I’m looking for, though. There is an ongoing paradox to the work we do, facilitating an anthology of prisoner poetry, when ultimately none of us wish it existed at all. It’s heart-heavy work — but here we are with Volume 10.

Because of my growing connection to Dreaming Inside I’ve found it difficult to plot out and write this review. There is by no means a poverty of literary commerce, much of this analytical work has been articulated in Aunty Barb’s introductions to previous volumes. I find it difficult because some books change your perspective on life and letters. Dreaming Inside comprises important historical materials across hybrid genres of poetry, life writing and political commentary. It should be essential reading at every law school in the country. Dreaming Inside is also a beautiful compilation of First Nations vernacular cultural transmission that disrupts closed readings of a text. Words and their political and aesthetic inferences leap from the page in ways that embody that characteristic of First Nations literature identified by Peter Minter and Anita Heiss — the nexus between the literary and the political.

For the milestone of Volume 10, the book was divided in two parts. The first is devoted to inmate contributors, the ‘Insiders’. The second part includes contributions from friends, supporters and project partners, the ‘Outsiders’, including Melissa Lucashenko, Jackie Huggins and Jim-puralia Everett-meenamatta, to name a few. I’ve had trouble with some of the correctional jargon; inmate, offender, prisoner all get caught in my throat. ‘Insiders’ and ‘Outsiders’ offers little conciliation, and though this nomenclature exists only as an editorial decision, it cracks open, lays bare, a vibrant, insubordinate language that challenge notions of poetic (en)closure.

I remember that first trip. We were driving to Junee and Wiradjuri land stretches out with a wide blue sky and open Country. Aunty Barb drives and yarns with actor Billy Mac. I’m listening quietly without taking my eyes off the Murrumbidgee, the way the grasses creep up clay banks lined with River Reds. The water has that stuff of legend swirling in it as Aunt circles back to stories and lessons sprung from the deeply embedded and cared for grass roots of Ngana Barrangarai program. I’d seen this river before but never travelled it quite like this. I hadn’t yet met the author of the poem below, Blackbird, a brother whose pen name would suffice as title for his otherwise untitled piece:

In her introduction, Aunty Barb offers insight into the imperative behind the anthology: ‘I have met many storytellers,’ she writes, ‘whose speciality is preserving the old stories, the Dreaming stories. My mission is to record and preserve the new stories, stories that will one day take their rightful place alongside the old ones […].’ Each time I take the journey I listen to more of Aunt’s stories, I listen to the fullas inside, I read their stories, and I’m looking at the river systems and tributaries and creeks thinking about how our old people reside and speak their sweet stories here still. I listen and connect the dots. I’m beginning to understand what she means.

‘I’m 20 years kid from Tumba-rumba the place I Call Home, in the Snowy Mountains, Near Murray river in Wiradjuri land.’

‘I’m a BarKinji men I’m from Wilcannia.’

‘I was arrsked to tell my story/ I was a Boy born in Albury

Mates Grandfather taught me Stories/ Sitting at the foot of the Hill at West Albury’

Readers will notice how many of the stories in the anthology begin with resounding assertions of cultural identity and connection to place that together puncture settler fantasies and fantastical doctrines of erasure. Beyond the immediate referential content of the writing, First Nations readers may also recognise a surplus of cultural information. These declarations of self aren’t simply recurring narrative motifs but relational protocols interwoven in ways that connect authors to notable knowledge-holders, landmarks, seasonal events and Dreaming stories. Allan Cochrane’s ‘River Song’, for example, speaks to and yearns for the nourishment that can be found through Country and community.

Pearl muscle shell black, lip, darker brown fish jumping out river.

Yabbies backing up a tree. Them crayfish found all the way up

to the Snowy Mountains. Used to camp that way, take the young

fullas. Show them how to do it, how to eat.

Dreaming Inside functions as an assortment of cultural and poetic markers on a relational and cognitive map, a way to trace some of the stories of First Nations people incarcerated at the Junee Correctional Centre. Dreaming Inside resists ongoing literary and literal carceral violences that situate Indigenous people as ‘once upon a time’ or ‘far, far away’ in a ‘state of nature’, or as faceless, voiceless silhouettes in prisons and landscape paintings. Kenneth Jones’ poem ‘the Serpent Snake Knowledge’ illustrates this better than I can:

Aboriginal trade rougtes

across country moving

along river, gravity

shift, pulling giant cod

from the water. I went

Tto a burial site where

the river passed.

[…]

What is said from story,

not just mine, shared,

colours inside our eyes –

Not just from my experience

Sent down generation

generation in your blood

handed down

in time we learned that

We the one’s Changing the universe.

All of us supernova become.

Self-determination, a key principle of Aboriginal cultural maintenance, underpins Aunty Barb’s editorial practice. I know first-hand the rigour with which she applies this principle. We’ve sat numerous times now in her living room, on her Country, transcribing hand-written manuscripts. Each and every single word, checked, doubled-checked, approved. I get a good growl if I accidentally ‘correct’ spelling according to conventional English standards. Even if there is clearly a typo, she has me question whether it contributes to the overall message but also whether it carries the impression of a moment in time and place. Readers of Dreaming Inside will and should be confronted by the unapologetic, ungovernable use of Aboriginal English.

In a previous volume of Dreaming Inside, while discussing inmate writing style, Aunt sets up an unlikely comparison to ‘literary greats like Dylan Thomas, Jonathan Swift and James Joyce (et al) [who] all played with conventional spelling and syntactical arrangements in order to produce a desired effect, often deliberately intending to challenge or shock.’ But, ‘unlike the re-imagined and re-constructed examples mentioned above’ — and here she delivers the sucker punch, diverts from the comparison and draws into alignment with writers like Lionel Fogarty — ‘these language differences are the real thing, not re-imagined, not re-constructed but wholly original’.

The supposed textual inconsistencies lead to a bittersweet reading that suggests a shared educational disadvantage but also an abundant vitality of Black vernaculars. Text, texture and context come together to evoke the sensory contrasts of confinement and freedom, incarceration and Country. Rather than inconsistencies, to me, the in(ta)mate grammars and spellings represent poetic apertures compelling readers to consider the historical conditions of their annunciation.

The fullas inside write poetry that resembles what Jessica L Wilkinson and Ali Alizadeh might call a REALPOETIK in that it demonstrates how poetic writing can ‘convey a deeper experience of reality and “real life” accounts’, as well as ‘celebrate[…] the power of the poetic form to realise and enact factual content’. Consider for example this excerpt from Graham Traegnor’s long poem ‘Chin Dip Push in the Yard and that’:

green clothes dont suit ya. Locked down again not knowing the future

walking the yard Trainin hard dodgin the guard

Dodgin the blue coats i row my own boat dodgin the guards just

Trapped in the yards.

doin etswaa nice to meet ya gonna send ya

The weak fall back to the Wall

eyes wide open im not copin strip searches & pat downs all the

Pod sounds

Everyone thinks They titan putem in the cell they frighten

Im on the news

Along with the rough stuff, Dreaming Inside dishes out a good blend of Black humour along the way. I’m reminded of Larissa Behrendt’s article on Aboriginal humour. Behrendt muses on comedian Kevin Kropinyeri’s assertion that ‘the flip side of tragedy is comedy’. Behrendt concedes however that with Black comedy and a lot of the content being circulated beyond those who might understand in-jokes, there is further risk of being misinterpreted in bad faith. First Nations people have to tread carefully for fear that they’ll only reaffirm the stereotypes enforced on them. It’s a type of cultural incarceration we’re all too familiar.

To be frank, I don’t think many whitefullas are ready to read this anthology. Maybe they’re not meant to get the in-jokes. These lines from Brett Burns’ poem, ‘Life’, sum it up nicely: ‘Caught up in this life With no Cunt to trust/ Back on topic/ What you know about us?’ Ready or not though, these inmate voices are loud, full of love, rage and redemption. You’re gonna hear ’em and you’ll be reminded that you’re outsiders listening in, because ultimately these poems are messages for their comrades behind bars.

But my Young Brothaz

open ya eyez

& Realize,

this livin aint life.

[…]

Whether ur on the concrete Streets,

Or these Steel prison bars,

u gotta conquer defeat

wit ur real livin scars.

Dreaming Inside is significant not only in terms of contribution to Australian literature but more importantly as a form of cultural continuity. In these generously offered works, the ‘Insiders’, the inmates, these offenders of colonial law, remind us that they are also brothers, sons, uncles, fathers, men belonging to an older Law. (I use gendered terms reservedly here as previous volumes of Dreaming Inside have also chronicled non-binary and gender diverse experiences of incarceration.) I conclude by turning to a quote from the ‘Outsiders’ section of the anthology. Melissa Lucashenko, who also launched Volume 10, tenderly expands on notions of Law, criminality and belonging explored in the anthology by saying ‘that everybody’s life is a sacred thing, to be protected by Law and cherished from birth to death – [this] is at the heart of our traditional culture. Lawbreakers Matter. So do their victims. We don’t chuck people away lightly.’

Volumes 1-10 of Dreaming Inside are available for purchase via the South Coast Writers Centre website.