To all the peoples of the old and true Australia, on whose land I have trespassed, and whom, by being part of my own people, I have wronged, I plead forgiveness. To all of them I owe that overweighing debt of life itself, and to all of them now I bend my head and say sorry. Sorry, above all, that I can make nothing right.

Shadow Texts

Joan Fleming on reframing the archive

Joan Fleming reviews two books that embrace the discomfort occasioned by reckonings with colonial monuments. While challenges to commemorative art are often characterised as destructive, Fleming highlights the creative aspect of these reframings.

On 26 January 2024, Invasion Day, in the early hours of the morning, activists carried their tools to the feet of a bronze monument of Captain Cook in the Saint Kilda suburb of Naarm, and they cut him off at the ankles. The fact that, even after rigorous debate and community submissions, the St Kilda council voted to resurrect the sculpture – unchanged – is proof of a dominant wish in our culture to chase that old feeling, the one famously expressed by the then soon-to-be-Prime Minister John Howard when he said in 1996 he wanted the Australian people to be comfortable and relaxed: comfortable and relaxed about our history, and comfortable and relaxed about our present and future.

‘Comfortable and relaxed’ is a big house in the Australian psyche. Living in the house requires that we never go into the dark room with the locked door. The house is decorated with the fictions that depict Australia’s founding: the valiant, hard-yakka efforts by colonists who did their best to bring Indigenous Australians along with them into a future of abundance and the fair go. The dark room with the locked door houses the knowledge that the country was founded on a largely unacknowledged frontier war in which the Indigenous population was bloodily defeated: through firearms, land grabs, mass poisonings, the building of roads and farms and infrastructure, economic disenfranchisement, and the silences and oppressions of the justice system. To go on living in the big house is a state that requires what Bonny Cassidy calls ‘the hardening of millions of soft denials into unknowing’. The question at the centre of Cassidy’s extraordinary new book Monument is exactly how those soft denials harden, and what might be accomplished if we opened the door of the dark room, if we let the severed boots stand.

Monument is a work of memoir, micro-history, archival recovery, and reckoning. Cassidy picks through, overturns, and handles the early European settler archive, pressing it for its obfuscations and avoidances, and making it reveal its acts of violence. She questions what the old monuments mean, and why we might need new ones. Even the title is a kind of erased monument: the strikethrough makes the refusal to honour public monuments hyper-visible. It is a kind of typographical red paint.

The book’s authorial voice tells the reader she is afraid of mystery, afraid of shadows. Yet the voice is also uncomfortable with easy declarations, with both the necessary inventions of fiction and the supposed truths of nonfiction. Cassidy insists on knowing the tricks a mind plays on itself in order to forget that, along with felled trees and decimated habitat, there are human bones ploughed under the soil.

One of the ancestral stories Cassidy reconstructs is that of her great-great-great-grandfather – a cobbler from the Prussian Empire who came to the continent looking for ‘fertile soil to steal’, then made his wealth in the Wimmera Mallee. Cassidy finds the holes in her grandmother’s oral history, the half-truths and obfuscations, and she fills them. In telling this story, Cassidy tells us a story of water. The fact of water, its presence and lack, obsesses the cobbler ancestor. He needs it if he is to successfully plough the bulokes into the sand, along with the middens, the stone tools, the millstones, and the human remains of the Wotjobaluk people whose Country it is. This action of active burying is familiar to me from Judith Wright’s poem ‘Bullocky’, where ‘plough strikes bone beneath the grass’. The bullocky drives his bullocks over this discomfiting truth. He pushes the skeletons down, as Cassidy writes, ‘further into his livelihood’, atomising the carbon remnants, destroying the history of place he never learns and, thus, can never speak about. When the bullocks are exhausted, he flogs his horses until he is charged for cruelty.

The breaking of the land, the tilling of the cattle-country, steals water from Lake Currong. Her great-great-great-grandfather’s toil, alongside the toil of other white settlers, turns the landscape into one designed by drought, its dust sometimes reaching the veranda of Cassidy’s bush block on Dja Dja Wurrung Country in the right directional wind.

Cassidy quotes her ancestor’s public letters on matters of agriculture and tillage. He calls for public money to fund the digging of irrigation channels. He writes how the earth here ‘cracks very freely’, how ‘there must be no more “squeezing”’, how the earth must be ‘scarified’ and ‘fallowed’. These are the agricultural practices that will keep the land productive, which he says he believes in: ‘I believe in the fertility of the soil’. What’s implied here – and Cassidy is a master of the charged suggestion – is the question of what he doesn’t believe in. He doesn’t believe in his own complicity; he doesn’t believe that the tools he holds in his hand threaten that fertility. He refuses to listen to the language of the drought.

This is one of Monument’s many histories, skilfully pieced together from painstaking research. It is told in italics, and those italics are interspersed with Cassidy’s own accounts of her visits to these places: Warracknabeal, Hopetoun, Rosebery. She writes of the bronze monuments to wheat and grazing that stand in Warracknabeal’s roundabouts. She writes of the new man-made lake that ‘sparkles painfully in the sun’. She writes of the murals in the town of Hopetoun, in which painted likenesses of pre-contact Wotjobalak hunters chasing kangaroo are somehow contemporaneous with ‘The Last Aborigine of Lake Currong’, Jowley, as an old man. In the mural, the colour of Jowley’s skin has for some reason been rendered white. In the picture, cattle drovers and a lone swagman walk away from the viewer toward the horizon line. Are the drovers moving ‘into the land of forgetting?’

The Hopetoun mural, a monument of sorts, is a synecdoche for the larger work of the book, in which Cassidy dextrously layers historical narrative with a persevering examination of the questions these narratives unearth. She is attentive to hauntings. ‘Rosebery,’ she writes, ‘is a ghost town where settlers go to haunt themselves.’ The hauntings cling to family heirlooms, like her great-great-great-grandfather’s bullock bell, which hung by the front door of her family home in Cronulla, and announced the arrival of a guest when it gave out (to quote Wright’s poem again) ‘a sweet uneasy sound’.

Cassidy goes to visit the stone remains of a pub that same ancestor built on land he ploughed and dried out and wished to scarify. ‘The air’, Cassidy writes, ‘is dented.’ That haunted, dented air echoes another image, a scar the ancestor received after he was knocked out by a drunk, which ‘heals into a pale dent like a tiny dry lake on his temple’. The damage to the land, then, rhymes visually with the damage to the man’s own body, though he is the one growing his wealth by breaking the stolen land. The emotion of the writing in Monument is exquisitely restrained, but when the images arrive, they zap like the touch of an electric fence.

This haunting, though, is beside the point, and Cassidy is quick to decentre it. She rejects her own fantasy of a fast-tracked reconciliation which might be achieved merely by acknowledging the ghosts of such places. Country, she supposes, does not hang on to these hauntings; it’s not Country’s job to accommodate a dwelling-space for colonial violence. Country has inherent dignity and rights. To quote Tony Birch, Country is not interested in a ‘white person’s melancholia’, nor does it draw its meaning from their narrative. In Monument, it is not Country that will hang on to this story. Instead, it will be carried by the storyteller.

So how does this storyteller define herself? What nouns does she reach for? Wright, in a coda of apology in her 1999 memoir Half a Lifetime, identifies herself as a trespasser. She wrote:

Cassidy, in her work as a critic, academic, and community member, defines herself not as a trespasser but as a guest. What’s the difference? A trespasser is a criminal. She sneaks. She peeps. She hurries. In order to accomplish her trespass, she must be quiet, preferably silent. She is trespassing in order to damage, or to steal, or to surveil. You can’t break bread with a trespasser, you can’t have a conversation. There can be only warning shouts, or warning shots. Or, maybe, a grim tolerance.

Trespasser, of course, isn’t inaccurate – and no shade on Wright, who was a leader in the work of uncomfortable remembering. There is, however, something expansive in the term ‘guest’, something that we settlers can use. A guest is someone whose presence is acknowledged through a ritual of welcoming. A guest, invited into a home or to a table, would be rude if they didn’t reciprocate the welcome of the host. They would be rude if they didn’t speak. They would be rude if they didn’t ask questions. A guest has responsibilities: to offer gifts, whether of objects, labour, or conversation. The old monuments, kept clean and intact, maintain a monologue rather than a conversation. In Reports from a Wild Country, Deborah Bird Rose writes, ‘The ethical alternative to monologue is dialogue […] It seeks relationships across otherness without seeking to erase difference’. The guest-host relationship honours difference: a guest is bound to the host, she is compelled by the host’s history: compelled to know something of their traditions. To pay attention.

Cassidy lives on, tends, and attends to a block of remnant box-ironbark bushland on Dja Dja Wurrung Country. It is a piece of property that insurers have declared uninsurable. The fire risk is extremely high. She writes: ‘When the fire comes and what’s left is my title, unextinguished.’ When the fire comes, and what’s left is my title, unextinguished – listen to the way the grammar of this sentence is left unconcluded. When the fire comes, well? The attending must still continue. Some structures will be lost. Country will be singed. The singe might stain; other stains might be lifted. Structures will require regeneration, rebuilding, reimagining. Country will continue. Cassidy writes, ‘It’s alive. It can’t be framed […] You can never see all the trees. / Because there’s a story already happening / you are standing in it.’

In such attestations – deeply self-reflexive, unflinching, subtle and sustained – the work Cassidy does in Monument offers a complex rejoinder to the cold, blunt instrument of the nation’s monumental No of 14 October 2023. It also offers a complex rejoinder to the bombastic vacuousness of the acknowledgement-of-Country-one-up-manship in liberal spaces, as well as to the reactive gatekeeping of good-faith, cross-cultural, philosophical inquiry from literary spaces. Cassidy’s rejoinder has ethos and logos – this is the work of a careful mind, one that takes pains to declare its position. Crucially, it also has pathos – a rhetorical appeal to feeling. The author maps the effect of this archival recovery work on her nerves; her voice braids concern and resignation over the inevitable fires that will burn her bush block; she tracks the flickerings of connection and revulsion towards certain ancestors, the threads of both identification and alienation.

Cassidy writes,

What I find in this book is a shadow text. A way towards something else […] I have thought a lot about what non-Indigenous people might contribute to the growing wealth of First Nations truth-telling. This book stands adjacent. I think of it as storytelling and sometimes, when it’s corroborated by sources that vary from colonial authorship, as history. While much of my work was meant to seek overlaps, the gaps in it show me what can be forgotten, what recovered, and what paths lie beyond the emblematic nature of a book.

Cassidy calls the book emblematic, insisting that it can’t stand in for the slow efforts of relationship building and community work – such as her labour in landcare and local radio. Rather, it stands alongside. But the storytelling and history-making of this book is itself a speech act, an action. The way the book makes the fictions of the archive visible is on par with actions that refuse to let public monuments of bronze and stone exude their quiet message that everything is all right: everything has always been all right. Be grateful for your big house, and don’t go into the dark room.

In his time, Cassidy’s grandfather came into possession of Benjamin Duterrau’s famous painting The Conciliation. The painting memorialises George Robinson’s ‘friendly mission’ around Van Diemen’s land. With the help of Woorady, Truganini, and others, Robinson made contact with the remaining Palawa people who were resisting colonial expansion. He persuaded the Palawa to give up and accept ‘protection’ from the settler government. Mob were then moved en masse to remote offshore detention at Wybalenna, Flinders Island. Cassidy writes ‘it is what we now recognise as, at best, a permanent detention centre; at worst, a concentration camp’.

What dialogue might have been afforded if the painting on display had been allowed to remain slashed? How can we, as Jeanine Leane suggests, rearrange and reframe monuments through a First Nations lens? Robbie Thorpe is willing to take them. I hear he’s planning a monuments theme park in the bush.

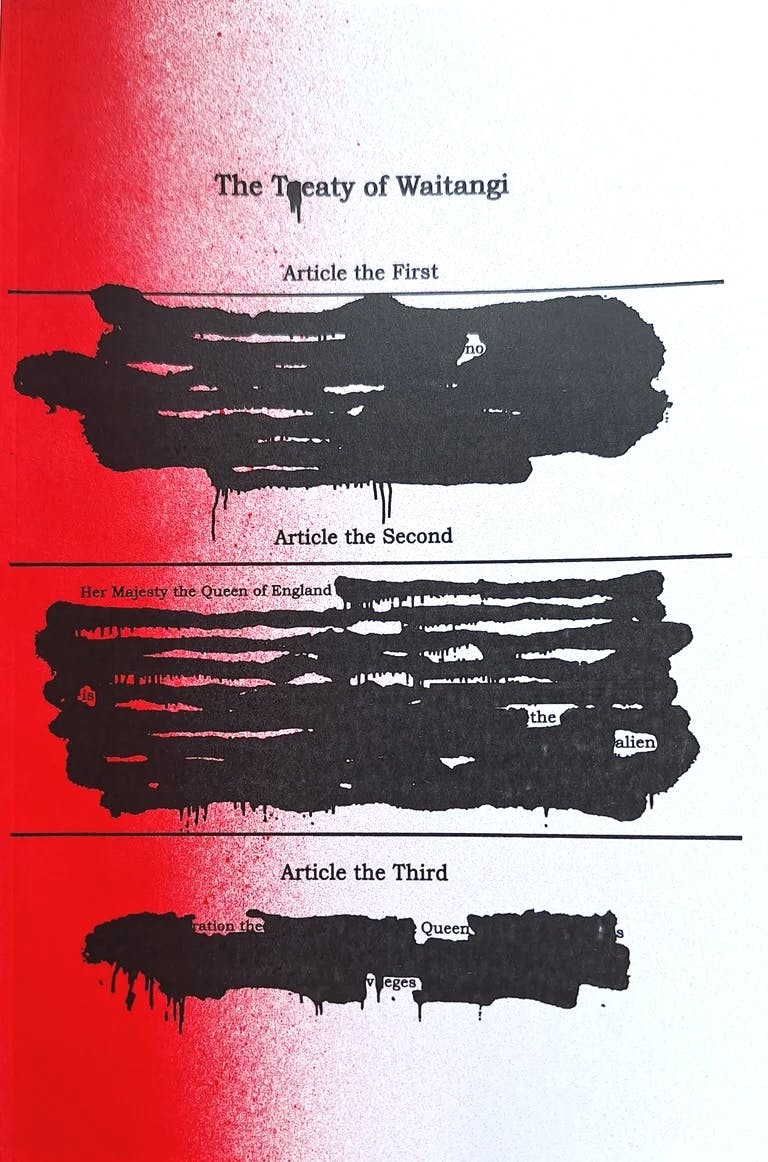

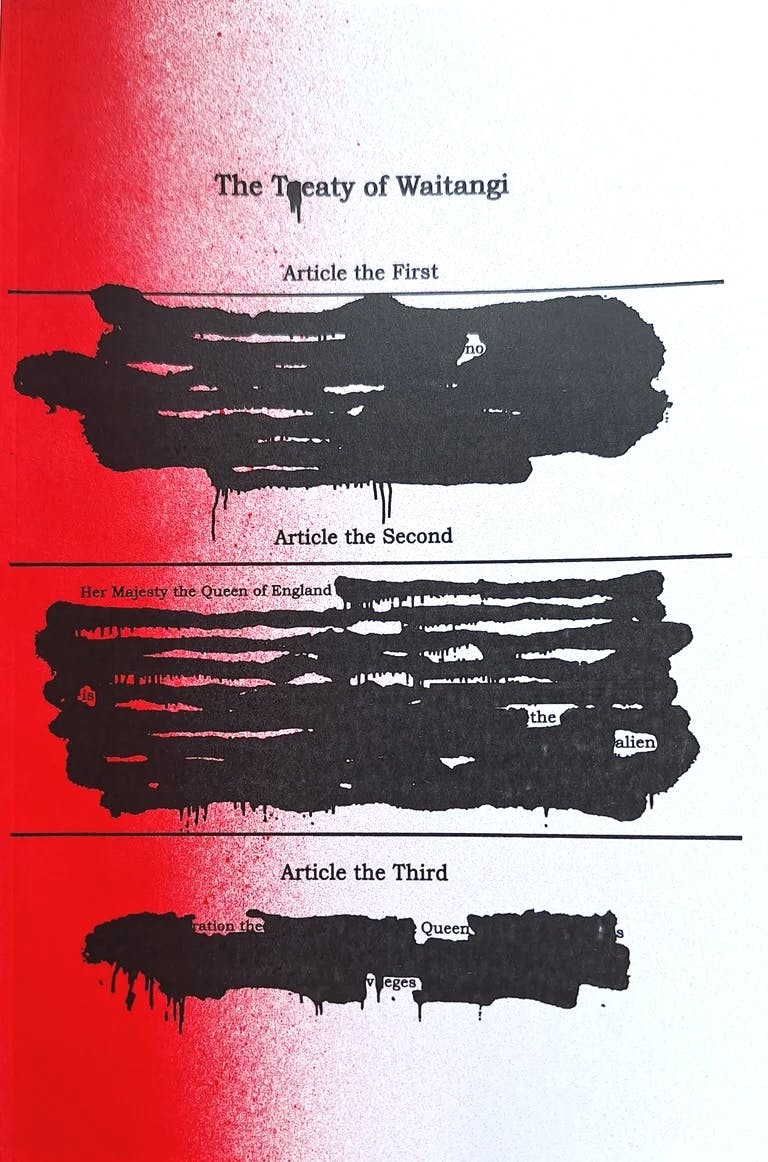

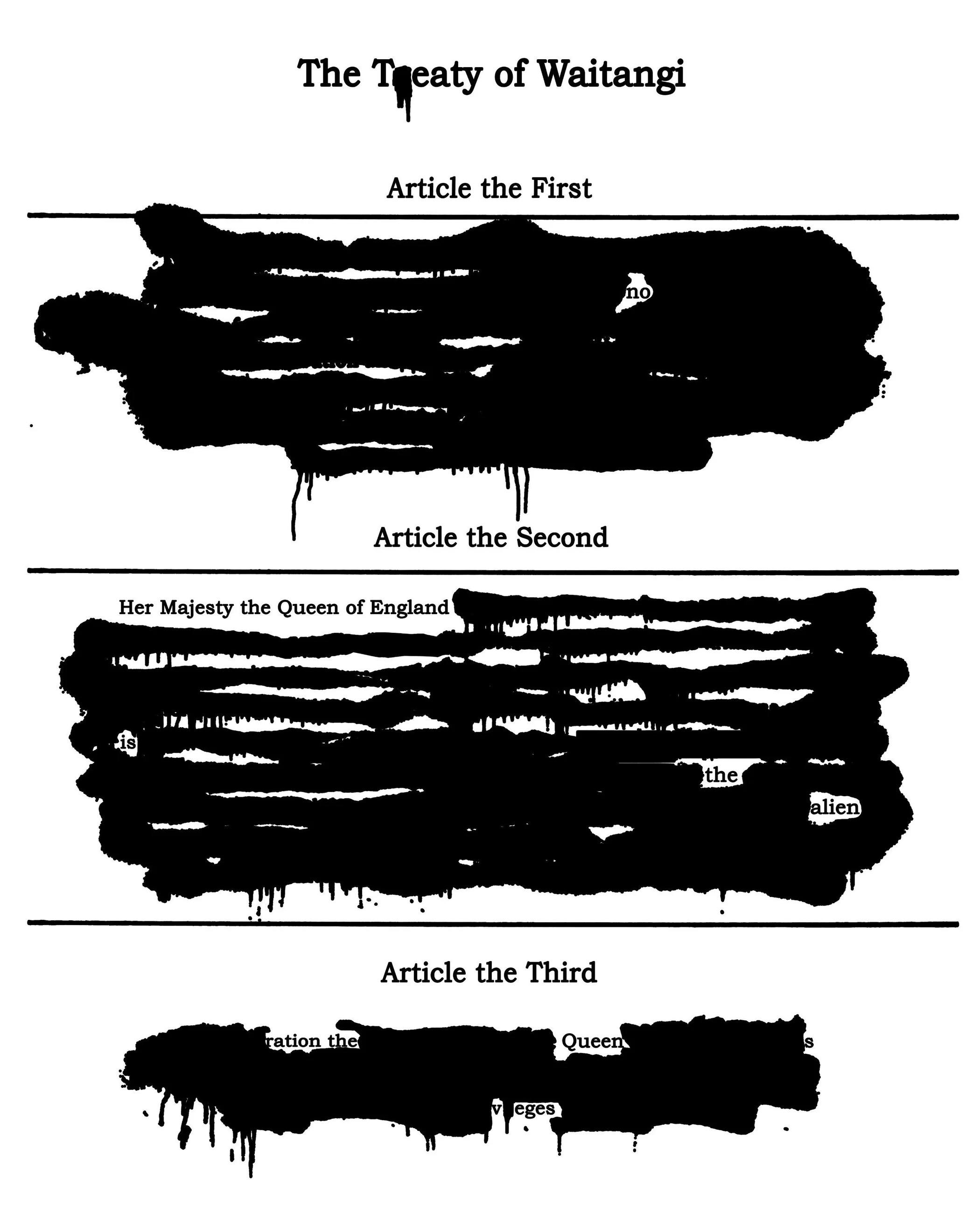

A recent action that effected such a reframing is documented in Te Waka Hourua’s book Whītiki, Mātike, Whakatika!, published by Wellington’s independent 5ever Books. The action took place in Aotearoa New Zealand’s national museum, Te Papa, on 11 December 2023, when activist-artists Te Waka Hourua carried in angle grinders and black spray paint, abseiled dramatically from the museum ceiling, and transformed the text of a wall-high panel of the ‘English version’ of Te Tiriti o Waitangi into an absurdist erasure poem.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi, or The Treaty of Waitangi, is Aotearoa’s founding document, and debates over its translation into English have intensified again with the election of a coalition government who have thwarted progress towards Māori rights and sovereignty with a range of measures, including the Treaty Principles Bill. The dispute over versions of the treaty dilates on the translation of a single word. Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the original treaty that was drafted in te reo Māori and signed by over 500 rangatira in 1840, cedes governance to the crown. The ‘English version’, created after the original and signed by only 39 rangatira, erroneously translates governance as sovereignty. At this time, Māori outnumbered Pākehā by hundreds of thousands, and te reo, not English, was the lingua franca.

Te Waka Hourua (‘the double canoe’ – perhaps a reference to the group’s Māori and Pākehā members) is a self-described tangata whenua-led, direct action, climate and social justice rōpū. Their book Whītiki, Mātike, Whakatika! gathers what might be termed ‘ephemera’ or ‘memorabilia’ associated with their Te Papa action, using a visual approach that is part photocopy zine and part coffee table art book. Its cumulation of documents and images includes photos of the action and snaps of whiteboard brainstorming and hand-drawn maps plotting the group’s planned movements through Te Papa on the day, screenshots of memes and posts that record both praise and censure, open letters from supporters in the wake of the action, testimonies from the participants, and texts that tell the history of the demands made to Te Papa, in the years and months leading up to the action, to change the Treaty display. By collecting these shadow texts – texts that shadow, or exist alongside, the action itself – into the emblem of a book, Te Waka Horua claims for them the status of historical record.

The nonviolent creative alteration at Te Papa (what news reports and museum staff called ‘vandalism’ and ‘defacement’) was an action of last resort. It took place after all other avenues of kōrero/dialogue had been exhausted, including emails, official complaints, and a sit-in in 2021 that lasted 181 minutes, one minute for every year since the signing of Te Tiriti – one minute for every year it hadn’t been honoured. Te Waka Hourua made a number of demands of the museum in mounting their action: to engage with Māori experts to tell the truth about Te Tiriti; to apologise for their misleading display; and to develop a free public education programme about Te Tiriti led by Māori experts. The ‘English version’ of Te Tiriti is not an inert translation, and its erroneous wording – not a shadow, but a legislative text: a tool of dominance – has shaped the principles by which government policy has suppressed the language, culture, land and sea rights, and economic self-determination of Māori in Aotearoa. Giving the two panels in the display what Te Waka Horua member Cally O’Neill calls ‘equal status’ and ‘equal prominence’ is tantamount to keeping this history in the dark room with the locked door.

The history of Te Papa’s ‘hardening of […] soft denials into unknowing’ goes back even further. Matua Moana Jackson was on the Māori Advisory Board to Te Papa during its design before 1998, but it seems Jackson resigned from the board after the executives refused to acknowledge the mistakes or ‘myth-takes’ that such an exhibition would perpetuate. In an email excerpt included in the book, Jackson writes:

They wanted the museum to be ‘Our Place’ but were very controlling about what that meant – including silencing most Māori stories about Te Tiriti. And the idea that Māori never ceded sovereignty was just too much I think. So the ‘Our Place’ is very much their place actually.

Professor Margaret Mutu from the National Iwi Chairs Forum and Network Waitangi Whangārei also lodged official complaints about the exhibition. In 2006, Te Papa told Network Waitangi Whangarēi that they would change the display. They never did.

Drafts and versions, then, are central to the debate around Tiriti truth-telling. Whītiki, Mātike, Whakatika! takes up the question of drafts and versions with a sense of playful subversion. The book gathers a proliferation of versions of the redacted English treaty text, including erasure poem options and drafts floated by the collective, and alternative erasure poems authored by members of the public in a tribute event hosted by Enjoy Gallery in the aftermath – an event that was also a fundraiser to help cover legal costs for the arrestees.

Te Waka Horua experimented with a range of tonal approaches for their ‘improvement’ of the display. Some of the drafts are all swagger, like the one that reads, ‘full / prop / s / to / the Chiefs’. Some retain the grammar of a legal document: ‘England confirms and guarantees / so long as / it is their desire / to alienate / the respective / half’. One draft uses wit, not to excoriate the crown, but to suggest ambivalence on the part of the rangatira: ‘The Chiefs / have / reservation // there / is / a / long / but’.

Image courtesy of 5ever Books.© Te Waka Hourua.

In the end, absurdity and brevity won out. Article the First of The Treaty is thoroughly blacked out except for a single, petulant ‘No’. Article the Second points the Othering finger at the crown, keeping the long-winded honorific but freighting it with sarcasm: ‘Her Majesty the Queen of England / is / the / alien.’ Article the Third is the kicker: ‘ration the / Queen’s / ve/ges’. This is the absurdist punch line. It’s the hook, catchy enough to keep being repeated, and repetition is central not only to Te Waka Horua’s project, but to spectacle-based direct actions in general. In the months after the action, I kept seeing reproductions of the erasure poem all over the city: in the feature window of Cuba Street’s Hunters and Collectors; wheat-pasted in duplicate on Wellington alley walls; framed and displayed in the elegant hallway of my colleague’s home; ‘Ration the queen’s veges’ stencilled on an electrical transformer box near my local park. A photograph in the book shows the phrase inked handsomely on someone’s forearm.

Documentation, multiplication, and repetition are central to the strategy of spectacle-based actions like these. As photographs and videos of such actions make the rounds on social and mainstream media, the discussion they generate is constitutive of the action’s enduring success or failure. If unsuccessful, the action disappears into a news void, or critique overwhelms public support and infects the reputation of the movement. If successful, the images might spur the conversation on the issue forward and inspire a proliferation of iterative actions and tribute imagery. Powerful actions enjoy an afterlife of iteration. The image of Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clark tearing up a copy of the Treaty Principles Bill in the New Zealand parliament in 2024, before she and fellow Māori MPs performed a righteous and chilling haka – and were swiftly kicked out of the Chamber – is another such example. I have seen this image everywhere since: on tee shirts, protest placards, stickers, online graphics, and in the halls of the university where I hold my current post.

In museum spaces, spectacle activism goes back to suffragette Mary Richardson’s protest, in 1914, when she took a meat cleaver to Velázquez’s painting The Toilet of Venus, slicing it six times. Richardson was a member of the Women’s Social and Political Union, and she was protesting the incarceration of union founder Emmeline Pankhurst. A spate of climate justice actions in museums in 2022 saw activists gluing themselves to a Picasso or throwing soup on a Van Gogh. Unlike The Toilet of Venus or The Conciliation, none of these artworks were actually harmed. They were all protected by glass, and Van Gogh’s Sunflowers was cleaned up and back on display in a matter of hours. Nevertheless, as the imagery of the action proliferated online, public censure outweighed public support.

The Just Stop Oil activists who authored the soup action were demanding policy change to prevent climate disaster. Their message was: ‘the cost of living crisis is part of a cost of oil crisis, and millions of cold, hungry families can’t even afford to heat a tin of soup.’ ‘What is worth more, art or life?’ activist Phoebe Plummer said to the media. One reason, I believe, for the loud clamour of public censure – even from those sympathetic to the cause – was the weak link between the cause and the image. A photograph of orange soup splattered on the famous orange and yellow painting had to stand in for ‘real action on climate’: the link is murky, and the viewer has to traverse several logical stepping-stones to make it make sense. This murkiness seeded confusion instead of buy-in, compromising public support for the cause. Like colonisation, climate change is what Timothy Morton has called a ‘hyperobject’: a happening that is mind-bendingly disparate across space and time. It is painfully difficult to sum it up in a single picture.

The link between the cause and the image in the Te Waka Hourua action, in contrast, was clean, and the ‘bunnies’ (those members inviting arrest) were tangata whenua who chose to be on the front lines, with tangata tiriti/Pākeha members in supporting roles. All this speaks to the keen planning and expertise of the collective, who executed the action with the swift choreography of a Hollywood heist.

While the wry, absurd humour of the erasure poem has contributed to the image’s staying power, Te Papa staff seem not to have been amused by Te Waka Hourua’s action. One staff member in Tours (according to documents obtained through the official information act) found the idea of calling the improved exhibit ‘some of the best art of our day’ to be, well, ‘Hilarious!’ To their great credit, museum staff consented to dwell for a time in the discomfort of the redacted display. They made the improved exhibition available to the public for nineteen weeks, and accompanied it with a sign letting visitors know that they were ‘working through next steps’. Now, the redacted panel has been taken down and is being stored by the museum. Head of Communications Kate Camp called the protest a ‘critical moment’ in the evolution of the museum, and expressed active ambivalence about what to do with the panel: on the one hand, keeping the panel could increase the ‘security risk’ for staff, and bring about more difficult conversations; on the other hand, these uneasy conversations about Te Tiriti are part and parcel of what she called the ‘historically significant’ action.

The historical significance of Whītiki, Mātike, Whakatika! lies in the book’s documentation not only of the action itself, but also of the many sites across which it visually proliferated: in art galleries, on the street, online, and even in the cells of the Rimutaka men’s prison. One of the most affecting sections of the book follows Te Waka Horua member Te Wehi Graham-Ratana’s story of the ‘lozzies’. Graham-Ratana was the bunny who abseiled from the ceiling during the action. In the aftermath, he was arrested and taken to Rimutaka to await his bail hearing. Before and during his processing, former inmates and prison staff alike kept telling him how important it was that he ‘get the lozzies’. Because prisons in Aotearoa have been smoke-free since 2011, the nicotine lozenges prescribed to help people quit smoking are ‘like gold’ – a currency on the inside. When he arrived at his cell, Graham-Ratana offered his jumbo box of lozzies to his cell-mate Brian, but Brian suggested, instead, that they offer five lozenges to every inmate who wrote a letter about their thoughts on the Te Papa action.

Graham-Ratana writes about the feeling in the prison block when word of the offer spread. He describes the laughter and kōrero he could hear from his cell – sounds of excitement infused with aroha, which, according to Brian, you ‘never hear’ in a place like Rimutaka men’s. Whītiki, Mātike, Whakatika! collects photocopies of these handwritten letters from a population of prison inmates that is majority Māori. They express their anger at the colonial deceptions around Te Tiriti, and the importance and power of Te Tiriti in their lives. Prisoners in New Zealand who are serving sentences longer than three years are barred from voting. I found it incredibly powerful to read this cumulation of shadow texts: democratic reflections from those who suffer keenly a legacy of 185 years of colonial disenfranchisement and violence.

Part of this essay originated as a launch speech for Cassidy’s Monument in February 2024, a week after activists made their rogue ‘Australia Day’ improvements to the St Kilda statue of Captain Cook. I worked on this article later that year from a bush cottage in Far North Queensland, on Jirrbal Country. I was a guest there for a while. On Fridays, I would go up to the local ‘Festival Hall’ for yoga. With the other white ladies and whitefellas, I would repose on the mat in safety. For a moment, I closed my eyes. At the far end of the hall, a mural depicted a group of whitefellas – settlers – posed beside Millstream falls, the widest waterfall in Australia. In the image, the loggers are relaxing after a hard day’s work felling timber, but somehow they don’t look comfortable. Their arms are crossed, their bodies blocky and awkward, their faces dim. A giant log is strapped to their wagon, and a boy stands next to it, his arms hanging by his sides. The log is larger in diameter than the boy is tall. On the mural, there is not a blackfella in sight. It is crying out for an alteration.

In Monument, Cassidy cites Michel Foucault: ‘knowledge is not made for understanding: it’s made for cutting.’ Te Waka Hourua’s book Whītiki, Mātike, Whakatika! – to bind, to axe, to rise up – collects documents that honour the playful Foucauldian cutting of knowledge. The work aims to help co-create a new monument to activism and education through the axing of one that stands. Just as interventions in public spaces are a way of reclaiming our citizen’s rights to co-design alongside the shrill visual litter of advertisements, a book like this asserts the right to create a counter-archive that disrupts the conservative dominance of institutions. As the Jewish-German art historian Erwin Panofsky reminds us, monuments are not only made of bronze and stone – they encompass actions and ideas that have the most urgent meaning for us in the present.

Similarly, Cassidy’s Monument both fragments the comfortable histories, and tries to pull together the archival fragments that tell a different story, one that she – as a writer, citizen, and guest on Country – is still coming to grips with. She also cites Paul Ricoeur: ‘one does not remember alone.’ She describes herself, sitting by a river, sketching the location of a Girai Wurrung eel trap on the Hoskins River – a picture her own ancestor had drawn in his journal seventy years earlier. In an admission of honest discomfort, she writes, ‘They make a childish weave, the lines that I draw from this hillside – between the trap, the inn, the river, the journal, the picture. They pull out in all directions; I struggle to draw them tight.’ The writing of the book is but a formative phase of the work. The next lies in following where the shadows lead: building relationships, looking after Country, staying attentive to opportunities, big and small, for reconciliatory action.