Ryan Ruby is well known for his literary criticism – often of literary criticism itself. Indeed, he is above all a critic’s critic. In his ‘A Year in Reading’ for The Millions in 2023, he notes his ‘professional concern’ for ‘reading the work of my fellow critics’, listing books by John Guillory, George Scialabba, Dan Sinykin, Emily Ogden, Sheila Liming and A.V. Marraccini as his picks for the year. He has tweeted that ours might even be a ‘golden age of popular criticism’, given some of the new affordances of the world wide web.

Critics tend to be not only reflectors but explainers. Insofar as they are called upon to give reasons for their judgements – which often include considerations about style, insight, consistency, and originality – explanation is non-negotiable. Such explanations are not merely reflexive but also justificatory: because of this and that this is that is the critic’s unavowed-yet-absolute article of faith. This reflexo-explanatory-justificatory fusion likely constitutes the critical déformation professionelle par excellence (if you’ll pardon the lapse into French), and entails, à la Ted Hughes’ shark, that one often finds critics tracking the most minimal trace of blood to their own sides. (Perhaps in the current epoch, whose mania for quantification is only rivalled by its disdain for egalité, we could nominate the basic unit of criticism the REJ, and use it to provide evidence-based assessments of criticism itself: ‘this is a 3-REJ critical piece’, ‘this critic has a REJ average of 10 per season’, ‘this review gets 2 REJs to the gallon’, etc.)

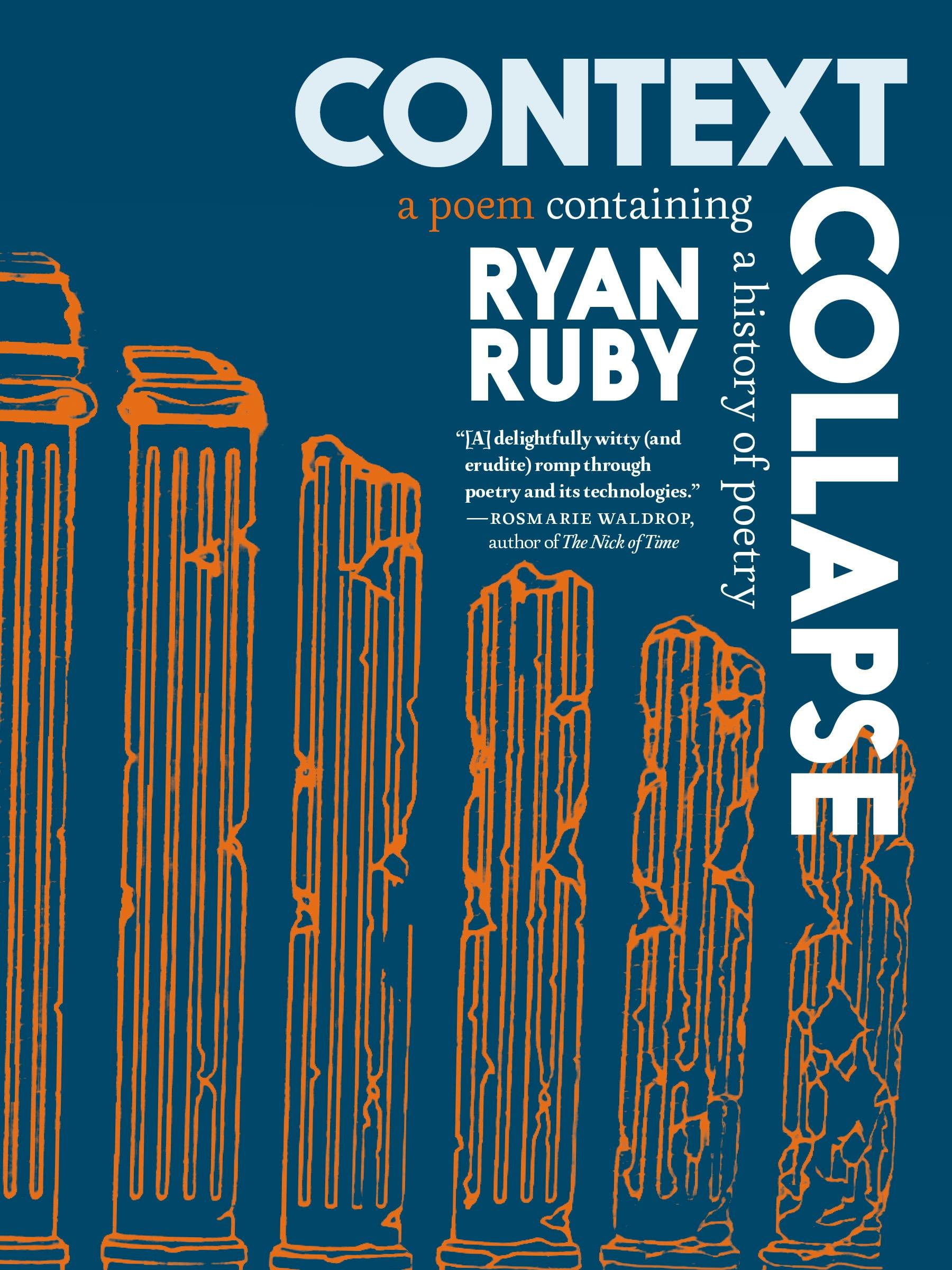

So it’s no surprise that Context Collapse: a poem containing a history of poetry opens with a dense seven-page ‘Razo’ at once reflecting upon, explaining, and justifying the subsequent 220 or so pages of this ‘verse essay’. Ruby dixit: ‘I offer the following remarks about Context Collapse with the aim of explaining some of my compositional choices and anticipating a few questions about the poem’ (my emphasis). That a poem begins with a prose explainer is by no means a new or even aberrant phenomenon: in English, one might think of the ‘Argument’ and ‘Note’ that the printer enjoined John Milton to append to his masterpiece Paradise Lost, or of the ‘Advertisement’ and then the famous ‘Prefaces’ that William Wordsworth inserted into Lyrical Ballads, or, in another European language, of the ‘Preface’ that the editors of Cosmopolis demanded from Stéphane Mallarmé for his radical 1897 experiment in poetic typography, Un Coup de dés. (I don’t mention these personages idly, by the way; all make significant appearances in this book.)

The term razo comes from anthologies of medieval troubadour verse, the word itself from the old Occitan for ‘reason’ or ‘cause’. Typically linked with the vidas, sketches of a singer’s life, from which they are not rigorously distinguished, razos provide compressed accounts of the circumstances of the poem’s composition. In Duncan Hose’s formulation, ‘They are prose pieces which pimp the lyric, lending it the glamour of a living thing’, functioning more as ‘mythic configurations’ than as matters of sober fact. Take the extraordinary razo (cited in Giorgio Agamben’s essay glossing ‘corn’) that introduces the world-historical rap-battle between Arnaut Daniel and his two eminent rivals: ‘Raimon de Durfort and Lord Turc Malec were two knights from Quercy who composed the sirventes about the lady called Milday n’Aia, the one who said to the knight that she would not love him if he did not corn her in the arse.’ Succinct, scabrous, salacious, the razo’s typically a primer for the sizzling scriptural raillery to come.

Let’s underline, first, that the traditional razo is informative but holds something in reserve; if it gives salient details of subjects and their places, their topical means and ends, it never tells all. Ruby’s razo, however, is not that: it distends itself from one earnestly diligent paragraph to the next. Second, let’s also add that razos and vidas were typically supplied by others, long after the death of the singers themselves; when the performers were alive, they’d have needed no such introduction. This clearly isn’t the case here, either – although these days the living on occasion introduce themselves as if they were already dead, or as if they were the posthumous editors of their own work.

If razos aren’t typically about giving an extended justification of the particular deep history of the genre of the poem itself, maybe this mutation is nonetheless continuous with the general spirit of our own critical golden age? Consulting the Wikipedia page for the Drake-Kendrick Lamar-J. Cole feud of 2024 seems to confirm this possibility: on the one hand, it serviceably describes an exchange of invective every bit as intense and inventive as those of the warlord singers we now call the troubadours; on the other, it’s as off-kilter and over-bristling with references as an anthology of cultural studies autoethnographies.

Is this what Ruby means by ‘context collapse’? (Just collapse, did it? Oh that cheeky context!) Not so fast, dear readers! For the answer to that question, Ruby teases, ‘you will have to continue reading to the end’. In the interim, thankfully, there’s always a subtitle to orient us. This is ‘a poem containing a history of poetry’, a post-colonic addendum functioning like that of any Anglo-American academic article in the humanities for the past fifty years. But that’s no surprise, either: in Ruby’s words, ‘Context Collapse is mock-academic in the way The Dunciad is mock-heroic’. Alexander Pope, confronted by Milton’s Paradise Lost – which appeared to him as at once the apotheosis and exhaustion of the epic, that most ancient, encyclopaedic and prestigious of genres – ingeniously responded by continuing the genre of ‘heroic verse’ by means of its satirical inversion. Does Ruby mean, then, that he’s intending to continue the work of academia by other means?

The subtitle does after all promise us ‘a history of poetry’. In other words, this is not just a poem, or even a poem about other poems, but a poem about temporally-marked ideas about a genre. But before we get onto that thorny issue: why specify, let alone write, a poem containing ‘a history’ at all? The ‘Razo’ expressly nominates Ezra Pound’s massive post-epic The Cantos as an authorising precursor, which Pound himself determined as ‘a poem containing history’. But ‘a poem containing history’ is a completely different concern from ‘a poem containing a history of poetry’ – indeed, a completely different kind of concern.

Pound was obsessed with poetry, not just with ideas about poetry, and his use of the word ‘containing’ is heavily freighted with both poetry and history. The Cantos ‘contain history’ in the very direct sense of being nourished by ‘real events that actually happened’ (if I can put it like that) as well as by how those events are told. This division within history becomes at once fuel and target for Pound’s poetry. Indeed, Pound – like his detested progenitor Walt Whitman – expressly contains multitudes, writing in an extraordinary range of voices, forms, styles, and genres, as well as performing their disruption. If you’ve somehow missed reading The Cantos, take this: