Hand and eye, the seeing eye, the right eye, magnified in the lens, extended turned monochrome red, or orange, or yellow green. Flattened. The film is infrared and I take each shot with and then without the red filter. Only with the red filter does the infrared band of light register on film, and on these shots when I print them I hope to find this invisible, metavisible light exposed, made manifest: the caul of radiance in which the seal pup was delivered out of the sea. Mirages and miracles, auras of breath, heat, decomposition.

The Caul of Radiance

Damian Maher on Beverley Farmer, grief, and the partial ecstasy of loss

Damian Maher considers The Seal Woman in light of Beverley Farmer’s fascination across her oeuvre with the threshold between life and death, rejuvenation and decay. Perhaps it is at this site of crossing where life is lived most vividly.

A dead seal pup has washed up on the beach. Beverley Farmer takes her camera and focuses on the light in the seal’s eye:

Her eye meets the seal’s. They almost become one. Then the camera intervenes and colours the seal’s eye, or rather, brings its colour to light. Initially, the catchlight’s hue seems clear and definite – monochrome red. Through the lens, the wavelengths shorten: red, orange, yellow, possibly green. The light Farmer wishes to capture, to expose, to make manifest is light she cannot see. Infrared film is sensitive to wavelengths beyond the visible spectrum, usually from about 700 to 900 nanometres. Black and white infrared film, which Farmer prefers to use instead of colour, etherealises the world, bleaching trees white and inking water and sky black. Infrared or contrast filters, like the red one she takes on and off, are used to block all or some visible light, allowing infrared rays to become visible on film.

Farmer hopes to reveal not the catchlight of a dead eye but the ‘caul of radiance in which the seal pup was delivered out of the sea.’ A caul is the amniotic membrane enclosing the foetus before birth. An en caul birth, where a baby is born with an intact amniotic sac, is said to be a good omen – the child will not drown. The ‘caul of radiance’ is the trace of creation – still, or perhaps only, visible in death. In Farmer’s eyes, this bourn of the born is also an interface between the material and the spiritual. Farmer takes several shots and passes hours developing the film in the red bromide light of a darkroom, trying to coax forth life’s evanescence. The hope may be in vain.

No photograph of the seal appears in The Bone House (2005), the essay collection from which this scene comes, even though other photographs by Farmer are featured throughout. Farmer does not say what becomes of the film. Instead of the sought-after revelation, Farmer offers the passage above. The final line is a list that descends from the spiritual and comes back down to earth: from mirages and miracles, to the brute heat of decomposition. Except, decomposition is not mere decay, but rather, the long, unmiraculous process of dead matter breaking down, giving way to new life.

Throughout her short stories, essays, and novels, Farmer often moves from the immediate presence of an eye, a fig, a ring, a jellyfish, a wave, a face, a shaft of light, a kiss, towards what she calls the ‘silken outflaring of life’, before returning to the tangible thing with which she first began. She shuttles between sensuous immediacy and mystic transit, hoping to glimpse here or there what D.H. Lawrence calls ‘the very white quick of nascent creation’. Looking upon the blossom and decay of a water lily, Lawrence, whom Farmer approvingly quotes in The Bone House, declares, ‘We have seen the invisible. We have seen, we have touched, we have partaken of the very substance of creative change […] the mystery of the inexhaustible, forever-unfolding creative spark.’ The sight of which leaves us, Lawrence concludes elsewhere, ‘most vividly, most perfectly alive’. Farmer is a more vacillating vitalist than Lawrence. She doubts that she (or we) can catch sight of the quick, whether in photography, writing, or life: ‘Not once, for all the intensity of my gaze, can I be sure of having caught the point of transition, shadow over to reflection, or back again.’ Moreover, she doubts that beholding the quick will prove enlivening or rejuvenating, even as she yearns for a glimpse. Farmer, and her characters, often seem to find themselves on the verge of revelation. It is there, on the verge, on the edge that whets doubt and hope, where she and they most vividly live.

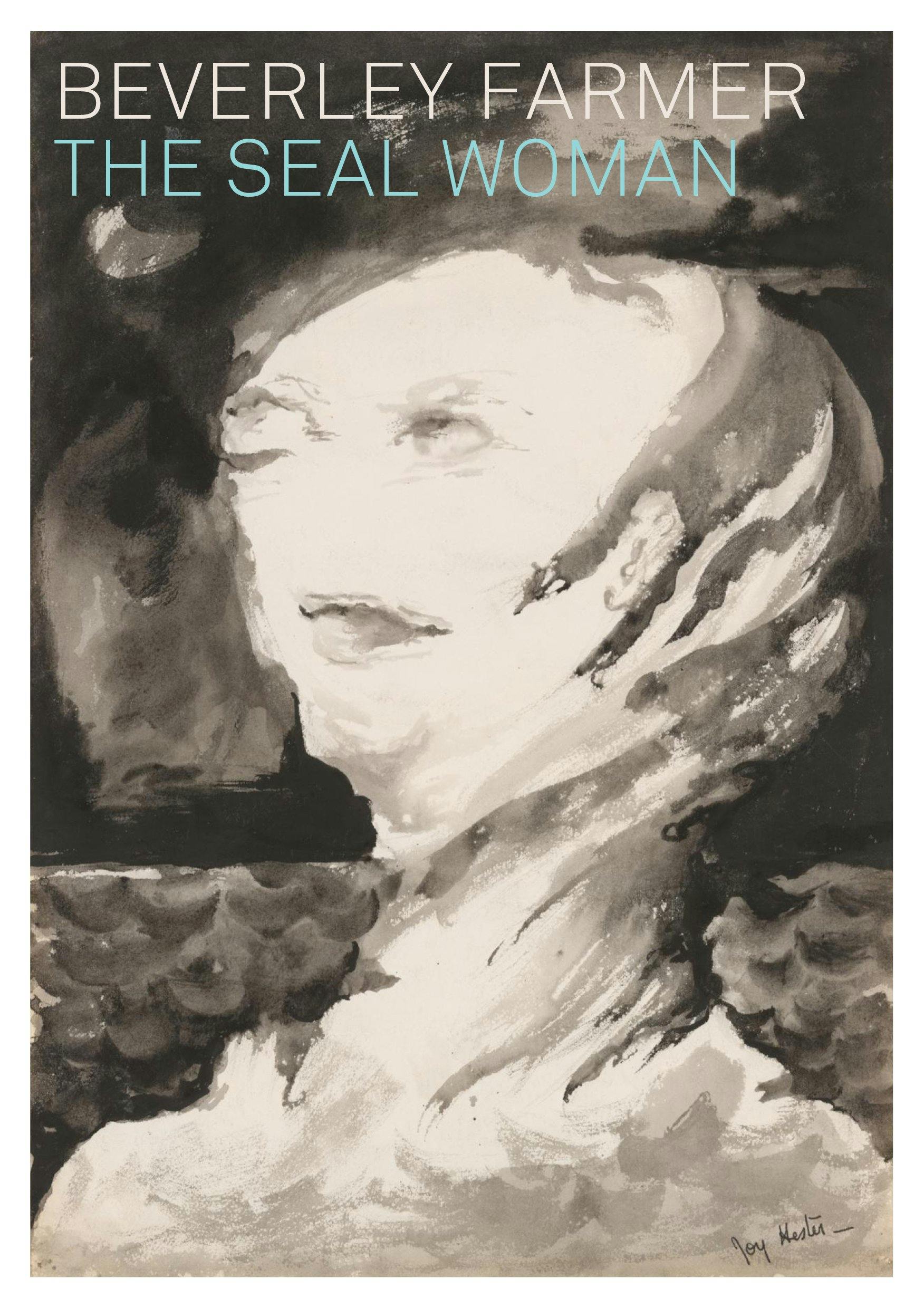

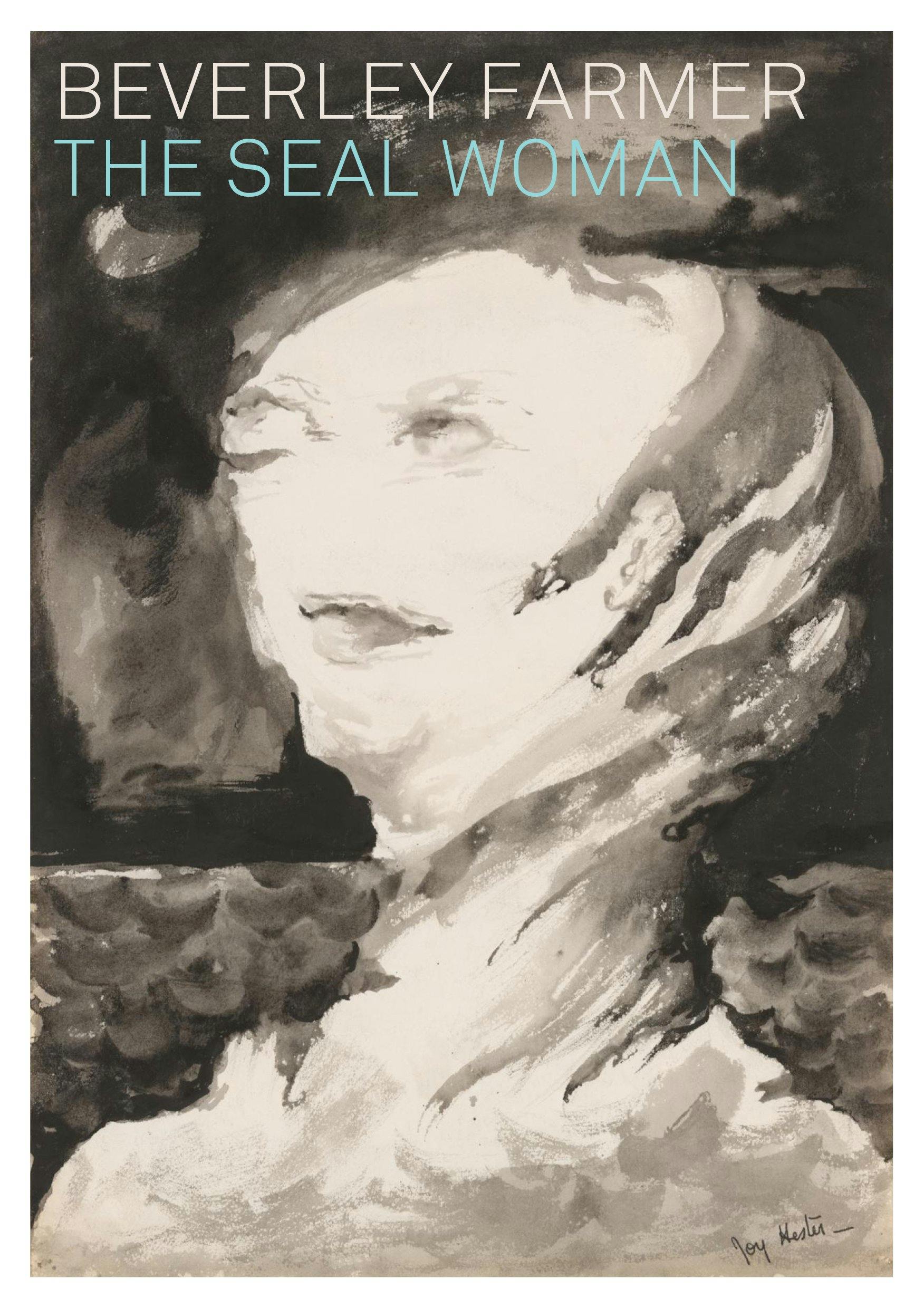

Dead seal pups as well as dead pelicans wash ashore in Farmer’s second novel, The Seal Woman (1992), republished this year by Giramondo. The novel is a topography of natural and personal peripheries, some as porous as a shoreline, others as precipitous as a bluff. The novel’s narrator, Dagmar, a middle-aged Danish woman, has been invited by her friends Bob Lawson and Fay to look after their cottage in Swanhaven for the summer. She met the couple years ago. She spent an Australian summer on the coast while her husband, Finn, worked aboard the Antarctic-bound icebreaker Nella Dan. Some years later, in 1987, Nella Dan hit rocks and was scuttled off Macquarie Island. Around the same time, Finn died in a fishing-boat accident off the coast of Århus. His body was lost at sea. A reader meets Dagmar a little while later. She carries a fir cone and a mussel shell in memory of the weeks she has passed searching in vain ‘along those tarred shores in the seaweed and shells and clotted rubbish for some trace, a sock, a cap, a fragment of flesh or bone.’ Childless (Finn was infertile) and having resigned her post as a primary-school teacher, Dagmar takes up her friends’ invitation and comes to the ‘far keel of the world’. ‘I come,’ she announces, ‘as Finn’s widow where I came once as his bride.’

Sites of foregone union became a regular haunt for characters throughout Farmer’s fiction. Dagmar likens Australia to an ‘underworld’. ‘Life here,’ she adds, ‘is life at a remove.’ The remove keeps her from grief, suspends time, and grants her space. Bell, the protagonist of The House in the Light (1995), Farmer’s third novel, undertakes a similar journey. She returns to the house in the Greek village where she spent time as a newlywed in Farmer’s earlier short stories, collected in Milk (1983) and Home Time (1985). This older Bell, fifty, divorced, and menopausal, returns to her former home at Easter. Although her exact reasons for coming back are unclear, she seeks out ‘moments of insight’: ‘Beyond reason we must trust in our moments of insight – even if at the same time we are convinced that there are no depths, that the soul and all experience are one flow of surface like shallow water, glinting and hollowing.’

In the wake of her loss, Dagmar skims the flowing present and plunges into the depths of her past. Simultaneously insensible and receptive, she has a porous intimacy with people and places. Martin, her difficult lover, likens her to a ‘sleepwalker’, albeit one with a certain ‘lightness, a shine, clarity’. She skirts the edges of caves, combes beaches, swims in the shallows. She reads books about polar ice that transport her south to the Weddell Seals, north to the Ringed Seals, which mate underwater, give birth in snow caves, and, according to intermittent news reports, are being killed off by polychlorinated biphenyls. The first time she and Martin have sex, she takes him in a dispassionate, almost uninterested, yet curiously caring way: ‘I made do with Martin in a space under the pier close up against the sea wall. A cave, it looked from there, buttressed down its whole length of sand with shadows then with water. Moth grey the sand slithered under the cape I spread out to lie on. I held his head down as he came, or’, she remarks, ‘it would have bashed up against the frayed logs.’ She does not (or does not wish to) notice the heaving man above her; instead, she traces the architecture of the cave, the sea, a squiggle of sand.

Such impressions make up far more of Dagmar’s narration than talk, action, or rumination. ‘Impressions’ may be the wrong word since Dagmar seemingly lacks the substance or solidity to be impressed upon. ‘It’s just like pouring himself into the sand. Sex. With me.’ Being in such a state enables her to absorb the gorgeous glut of the natural world, even if she often leaves it to ‘you’. After likening the skin of a lychee to the pelt of a sea urchin, she describes other fruit as though pointing them out in a still life: ‘There is a cactus fig or pear with a purple skin and spines with a sting, so you have to hold it down with a fork to spoon out the hard seeds and the beetrooty rødgrød, a jelly that bleeds and is better when it starts to ferment.’ This abstract ‘you’ beholds the sea: ‘When you hold a mask on the surface of the sea and look through, it is as if you held the sea in your hands. It stills, it moves enlarged in slow motion. The lifting of the mask is like a wind.’ A spectre, Dagmar moves through and observes the world without displacing it; submerged, she enjoys an uninhibited, primary affinity with all sorts of things. The world dials up and dilates when you are not present enough to hold it steady: ‘The sunflowers in the water glass on the sill have become crowns of flame suspended in radiant midair. The whole window is heat and orange light, the walls, and the ribbed sheets and limbs sprawled out are plumes, shadows, hollows of fire.’

Neither fully here nor there, Dagmar lives in the half-life of her past. Sometimes, she slips placidly into it. Taking a rowboat out to sea, she loses her bearings. She sinks into a slow undertow of dream-like memory, where Finn unhurriedly paddles ‘from side to side and the round nets he flings of wave on wave over the shores of sleep’. Sometimes, her past capsizes the present. Martin accuses her of having slept with Bob, another man in town. Dagmar recalls (and recounts) telling Finn that she had slept with a Greek man called Janni. She fell pregnant. Finn beat her on the ship on their way back to Denmark. Too far gone when she landed, she had a backstreet abortion. Sometimes, the past and the present lie side by side. Finn and Martin overlay in her mind and her bed. Sometimes, past losses act as a solvent; other times, their residue binds. ‘Is there a figure of speech,’ Dagmar asks Martin, who is recently divorced, ‘to be frozen with grief? He [Martin] in his grief was like a river clotted with slurries of ice, and that was as much a bond between us, I should have thought, as a barrier.’ Grief can function as a slurry, clotting individuals together, even if the loss is isolating, the pain numbing.

The partial ecstasy of loss, the hallowing of grief, the unbalanced vibrancy of despair had long fascinated Farmer. Her first novel, Alone (1980), chronicles eighteen-year-old Shirley’s anguish, obsession, and yearning over two days and nights in 1950s Melbourne following the end of her relationship with Catherine, who once told her that she was ‘absurdly preoccupied with the surface details of life.’ In response, Shirley asked, ‘But where does the surface end?’ After their breakup, Shirley’s preoccupations turn fervent. Rereading The Waste Land, Shirley sees in a passing tram ‘a boat of lights on the rain-furred street seamed with four sleek rails.’ Above, ‘the moon hoists high its yellow bladder, swells, spills, shrivelling over the water.’ Shirley’s excessive ardour, her brimming metaphors, which later provoked embarrassment in Farmer, might be seen as the opposite of Dagmar’s detached perusal; Shirley wills transfiguration, Dagmar lets things slide. Yet, they are of a piece; both enter a keen torpor begotten by bereavement. In This Water (2017), Farmer writes, ‘Name the widow Zoe. Ζωη, Life.’ Her name speaks either of life regained after loss – renaissance is the goal – or of loss itself as strangely enlivening.

The drive to recuperate courses past these more languorous eddies in A Body of Water (1990), the forerunner to The Seal Woman. Part commonplace book, part poetry and short-story collection, part journal, A Body of Water chronicles the period from February 1987 to 1988, during which Farmer attempts to write, read, walk, swim, eat, and live her way out of a fallow period following the breakdown of her marriage to a Greek immigrant. The pair had lived in a Greek village for several years before returning to Australia. In an interview given in 1990, Farmer declared that she left the marriage because she could not get over two miscarriages, in the tragic light of which, her stooping to photograph the dead seal pup appears a creative sublimation, ‘the caul of radiance’ a surrogate for a shroud. Or rather, it is a moment where revelation as the disclosure of the supernatural meets revelation as the exposure of something previously unknown. And yet, she does not glimpse the caul or capture it on film. Α Βοdy of Water drifts between the hope for recovery – regaining the ability to write, to produce, to be fertile will prove life-affirming – and the strange allure of life found wanting, bereft of redemptive potential.

Farmer, as Dagmar does, seeks restoratives. She too attends life’s little pleasures, often in the second person: ‘There are two long, metal staircases from the clifftop to the beach. When you walk on them in wooden-soled shoes or thongs they chime and resonate; when you run, the small sounds shimmer together like gamelan music.’ She and Dagmar both find useful men to lie with. They both keep notebooks, Farmer likening hers to a placenta nourishing her stories. They are both fond of dictionaries and encyclopaedias, which reintroduce them anew to the world. Names of various seaweeds – ‘seawrack, bladderwrack, kelp, sea lettuce. Stonewort, thongweed. Cystophora. Sargassum’ – succeed the thought that if Farmer’s miscarried child had lived, the child would have been twelve that month; even when dead, the child does not stop growing up. Many of Farmer’s affirmations read like ascents, as though she is kicking to swim upwards and regain the surface. She reads Sylvia Plath’s Letters Home and selects a hopeful letter Plath wrote to her mother: ‘I need no sorrow to write; I have had, and, no doubt, will have enough. My poems and stories I want to be the strongest female paean yet for the creative forces of nature, the joy of being a loved and loving woman; that is my song.’ A few weeks later, Farmer confesses that every time she tries to write a new story, she is brought face-to-face with her reflection in a mirror and cannot proceed.

Reading shows her a way on. A Body of Water overflows with citations. Alongside works on meditation and Buddhism, Farmer references modernist writers such as Eliot, Lawrence, Mandelstam, Rilke, Woolf, and Yeats, as well as many of her most interesting contemporaries. Berger, Burgess, Byatt, Duras, Durrell, Frame, Handke, Heaney, Lowell, Matthiessen, Munro, Murnane, Naipaul, Paz, Plath, Snyder all make appearances. Farmer begins the book by citing ‘words of hope – perhaps’, from Octavio Paz:

By a path that, in its own way, is also negative, the poet comes to the brink of language. And that brink is called silence, blank page. A silence that is like a lake, a smooth and compact surface. Down below, submerged, the words are waiting. And one must descend, go to the bottom, be silent, wait. Sterility precedes inspiration, as emptiness precedes plenitude.

The ‘perhaps’ she adds speaks of her wariness – the descent will be abysmal and goes against her instinct to return to the surface – and her doubt that abundance lies on the other side.

As the months pass, Farmer comes to conceive experience as a threshold or as taking place on a threshold, a term she adopts from Peter Handke’s Across. A threshold, the bottom of the doorway crossed to enter a house, marks a limit. A pain threshold, for example, is the lowest intensity at which a stimulus causes pain. A threshold is, however, both a border and an onset or outset, a point of transition: the threshold of a new age, of revelation. The Priest in Across pronounces the threshold to be a passage, a seat of power, ‘a fountainhead’, a dwelling place. Farmer’s women, Bell and Dagmar, return to bygone places, drawn to live, for a while, in bardos, where instead of epiphanies, meanings transpire. ‘We know, from experience, how all experience has its meaning beyond the moment,’ writes Farmer in The Bone House, ‘a meaning which is only ever gradually revealed and grows with the revelation. The process is always incomplete. The meaning goes on growing, like desire, like memory, in the dark. The fullness of the meaning is only to be known by its weight, its power of displacement.’ What, however, is being displaced?

In The Seal Woman, it appears to be Finn who is displaced, or even replaced by a growing revelation. Dagmar does not mourn her loss. Any question about Finn is met with a ja and no further comment. She does not come to bask in a pantheistic providence or find herself restored in the temple of everyday things, as T.S. Eliot did with Roger Vittoz. Dagmar falls pregnant. One day she pisses, and she knows from the hot malty smell that she is with child, or rather, foster, as she learns a seal foetus is called from one of her books. She decides to call it Finn if it is a boy. She does not tell Martin. She is hurt by his infidelity, which she has failed to notice until he pulls away from her, even though the warning signs were all there. She leaves him, saying that it was good to have been in love somewhere along the way. She announces that she has shed the burden she came with and can now return home, repeating the boat journey she made decades before with Finn and her first foster. Her narration allows no room for a reader to question whether she has truly found release, or to doubt the course of action she takes. Given all that Farmer has written on the unstoppable germination of experience, past pains cannot be relegated to the past, even if fresh water wells up, seemingly from nowhere. As she nears home, Weddell seals call beneath the ice. At the window of the boat, at the mouth of a white cave, is Dagmar, ‘pooled in lamplight […] a speck in a yolk, in a soft shell, worlds within worlds of burning luminous white.’

Despite the scene’s hermetic beauty – or to balance out the symbolic (over)investment in an unplanned pregnancy as a halcyon redemption – the novel does not end here. Dagmar has left a story for Lyn, Martin’s daughter. The story is called ‘Sœlfruen’ and makes up the last pages of The Seal Woman. It is a tale about a fisherman who marries a selkie, the mythological creature that shapeshifts between seal and human by taking on and off their sealskin. The selkie leaves him one day and returns to the sea. An old man gives the fisherman a sealskin so that he can recover his wife. He then hides her sealskin so she cannot escape again. One day, she has a vision and uncovers the hidden sealskin. She leaves her wedding ring on the table and flees once more. The fisherman scrambles down the shingles to the sea, calling her name. ‘Then he plunged in and sank swaying and grasping at kelp to the seabed.’

This is a vindictive story to give to the daughter of a former lover who is trying to patch things up with his ex-wife while sleeping with someone else. It is also a terrible rendition of Dagmar’s own loss. She has scoured the shores just as the fisherman in her story calls out, clinging to kelp on the edge of the shelf break. Perhaps writing the story unburdens Dagmar, however difficult it is to hear any note of release in the fisherman’s broken cry. Perhaps, the story confirms Dagmar’s revival: she can create life and create art. Or perhaps, the story lets loose a mournful howl and sets death, in all its obduracy, against the hope that life succeeds death. Near the end of the first essay in The Bone House, Farmer has a bleak premonition:

I see now that the story will never unfold, in the form of waves of living opening water or any other form. It was a freezeframe all along, fixed in a moment, the explosion at the core, the cauldron, the death pang – not so much loosening water as the stone that has broken through its ceiling, repercussing, is the story. Not even water but frost growing like coral, crystal by slow crystal. A marbling of blood on snow, on cloth as cold as stone – a death mask, a red nimbus.

Even though the pang, possibly of a miscarriage, is instantaneous, and the loss freezes, clots, chills, crystallises the flow of life, a red nimbus is the direct counterpart to the caul of radiance. They are both luminous promises that life and death might have meanings beyond themselves. But the story Dagmar gives Lyn has no halo. It ends at the edge, where the fisherman holds on for dear life.