The poem does not exactly hover on the cream-white page, but is partially embedded, the paper embossed with type which is not evenly printed: ‘spelling’ holds less ink than the bold black ‘out’ which follows. At the time, ‘furkan’ meant nothing to me. It was merely a sonorous word inserted between ‘rags’ and ‘streams’ and ‘other names’. I was caught by Barnett’s ‘edge’, his ‘grasping grids’ and the poignancy of ‘old roads’ leading to another road, leading eventually to the sea, ‘when we sail’. I perceived such bittersweet regret in Barnett’s verses that I imagined his destination to be Avalon, the elysian isle of Celtic legend, where heroes might eventually find peace.

Marian Crawford is co-ordinator of the Printmaking & Artist Book Studio at Monash University. With Barnett’s permission, long before the Wakefield Press publication was mooted, Crawford began setting each poem in Gill Sans 10pt type, which she printed in a single column on 120gsm Velata Avoria paper measuring 23cm x 21cm, on a small hand operated letterpress. There were then some two hundred and fifty poems – there are now over two thousand. This will be the labour of a lifetime. For Crawford, an essential part of her process is the ‘critical transformation, from a quickly forgotten moment in the blur of historical conflicts and live news feeds to an object that demands slowness in both production and reading’. Her slow process results in an intimate knowledge of the text – letter by letter, so to speak. In this loving commemoration of the poem and the poet, the book of the text becomes a work of art.

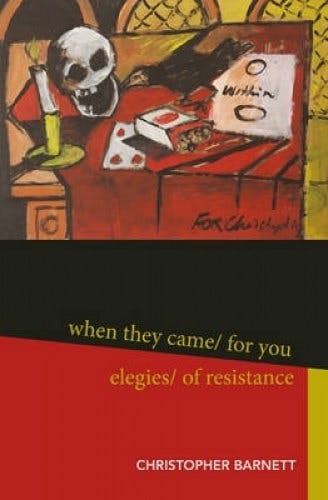

I am privileged to have read my first poem from when they came / for you elegies / of resistance in Crawford’s elegant setting. Though I commend Wakefield Press for taking on a far from standard publication, there is no doubt that the aesthetics of the page – the feel of the paper, the faint indentations caused by hard type, and the almost palpable smell of ink – influenced my reading of the poem. Crawford’s page, curved like a wave, is as wide and open as Barnett’s recurring motif of the sea. The poem is imbued with a gravitas and jagged beauty with which the cramped double columns of the paperback cannot compare.

Barnett’s customary style in his earlier published works, collected in LAST DAYS OF TH WORLD. And other texts for theatre (1984), and in the ‘(interlude)’ and ‘(interlude within interlude)’ of when they came / for you elegies / of resistance is a telegraphic, non-grammatical prose, without capitalisation and generally punctuated by slashes or ellipses. The slashes in particular create a sense of momentum, a forward rush. Soon after Doğan’s death, Barnett’s outpourings of grief, empathy and rage began to appear on his Facebook page in staccato phrases or single words typed one under the other, with only line breaks, spaces and a rare comma as punctuation. The form lends itself to the downward scrolling of computers and smaller devices. Having looked back at Barnett’s Facebook archive, I see that on some days he posted several poems, on other days none. Contemplation and suspense were imposed by the time lag between posts, and by the comments, images and other postings interspersed between the poems. The online reading is fragmentary by nature.

Collating Barnett’s poem-posts must have been a formidable task. Assembling them into a three hundred and twenty page book set with two columns per page imposes the idea of a continuous narrative that requires cover-to-cover reading. The twin columns, though expedient, compress a text which thrives on spaciousness of both time and page. Were this review not imminent, I would have preferred to read the text like a book of hours, a poem a day over several years, each day a meditation on the fate of Doğan, of dissidents, activists, and the artist-poet’s place in this imperfect world. My speedier reading served to highlight repetitions – a legitimate poetic device especially suited to Barnett’s performative work. But at a certain point I was fatigued by the poet’s interminable exhortations and seemingly endless litany of atrocities. Only later did I realise that I had taken on the poet’s fatigue. I was weighed down by his disillusionment, regret and occasional hopelessness; I was drowning in his refusal to forget.