To be modern is to find ourselves in an environment that promises us adventure, power, joy, growth, transformation of ourselves and the world – and, at the same time, that threatens to destroy everything we have, everything we know, everything we are.

Ways of Being

Anthony Macris on genealogies

Anthony Macris reviews two books that afford an intimate glimpse into the formation of two intellectuals, George Kouvaros and Nikos Papastergiadis. In their stories, Macris sees the pathos and prodigiousness of the changes wrought by modernity.

In his 1983 study of modernity, All That is Solid Melts into Air, Marshall Berman wrote:

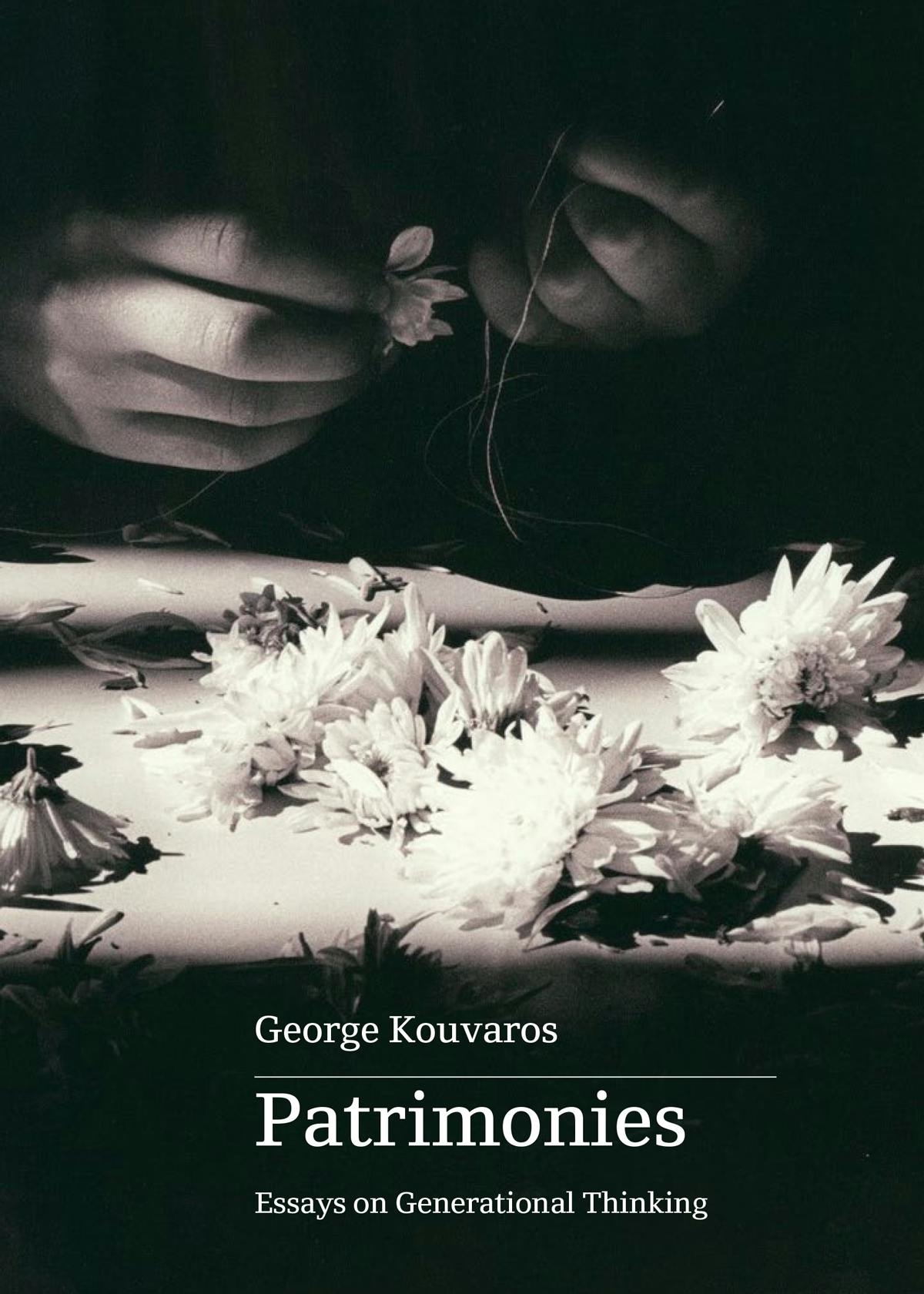

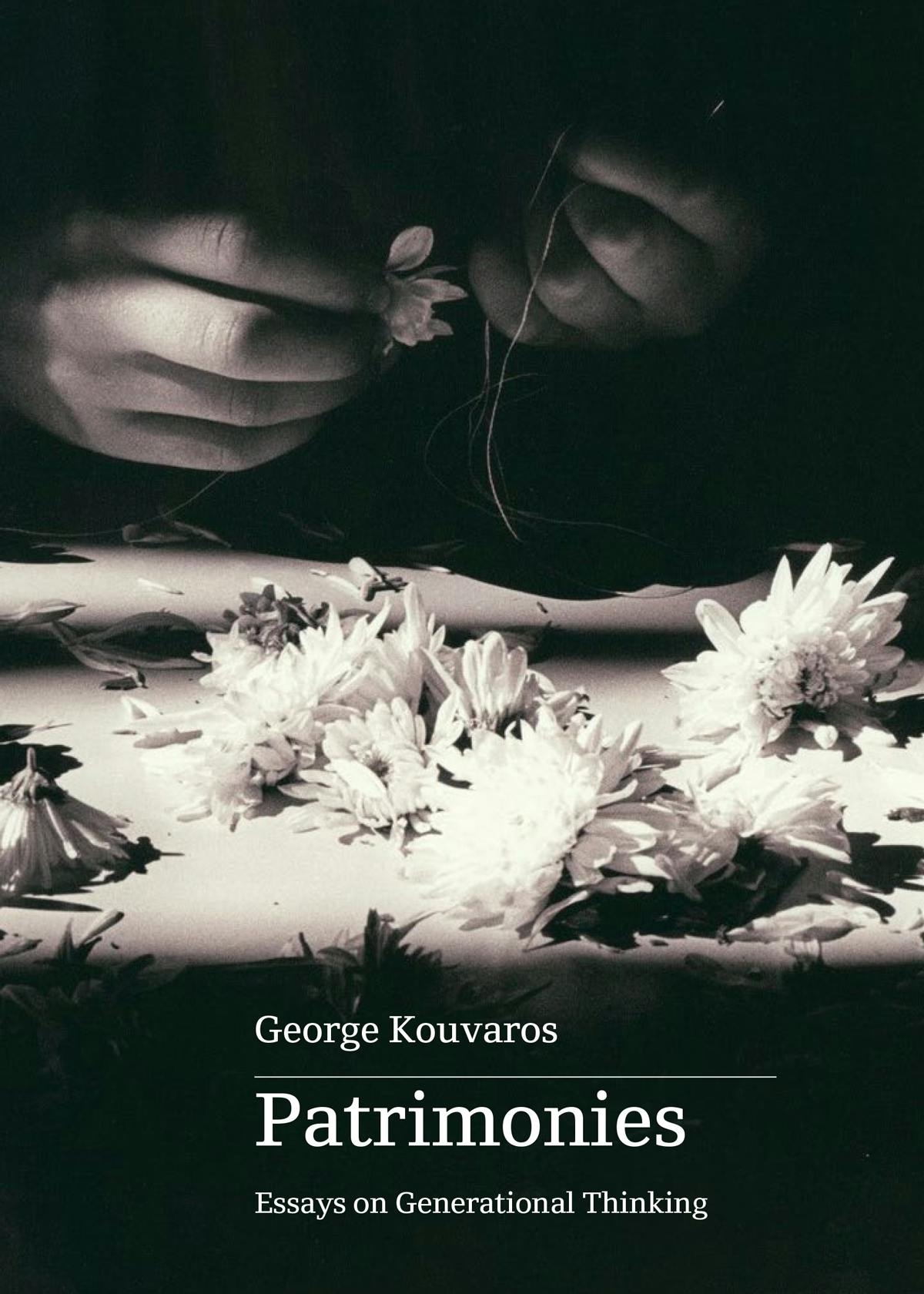

Berman’s words kept going through my mind as I worked my way through George Kouvaros’ Patrimonies and Nikos Papastergiadis’ John Berger and Me – books that engage deeply with the tensions between the modern and the pre-modern, between transformation and tradition, between the historical and the personal. Both are accomplished scholars: Kouvaros in film and media studies, Papastergiadis in sociology and cultural theory; their intellectual interests and theoretical reference points are thus wide and varied. Yet a common foundation for their insights is their Greek background which features autobiographically throughout their books.

Their work sheds light on numerous existential and ethical questions: what it is to be human, to be a friend, a son, a thinker; how we become who we become over generations; and what we owe to those generations, particularly our parents’. Both Kouvaros and Papastergiadis are concerned with one of the key modernising aspects of history: immigration and its aftermath – and not only in terms of geography, but also across social class and identity. Their interest is as personal as it is scholarly. Both are born of Greek parents of peasant backgrounds who came to Australia in the great wave of immigration from a Europe shattered by the Second World War, and that occasioned the biggest transformation in Australian society since this continent was claimed by the British crown. Their exploration of the lived experience of migration over time, across generations in fact, is informed by a sophisticated conceptual machinery that draws on continental philosophy, aesthetics, and much else besides.

George Kouvaros’ Patrimonies is a subtle and moving collection of essays that uses a blend of criticism, cultural history, and memoir to achieve its aims. It’s the work of a thinker who cares deeply about humanity, strives to understand it, and uses his formidable erudition to grasp something elusive just beyond where he is. The idiom of his thinking is grounded in specific disciplines – film and photography studies, philosophy, aesthetics, literature – but these are simply the means to explore questions that affect us all, and whose provisional answers shed light on what it is to be human. At no point does he lose sight of striving to understand his main concerns: the nature of our debt to others (especially our forebears), how our identities are shaped by those close to us and by the social and historical circumstances we find ourselves in, what it means to live in an unstable world, where we teeter on the crest of a wave that recedes behind us at the same time that it propels us forward. As Kouvaros writes in ‘Pacific Park’:

How can we speak of places where families with limited means came and went, and made a living of sorts, places that act as meeting points between the old and the new, the long-established and the newly arrived, where each generation is given the opportunity to see itself as different from the previous one and hence able to break away? […] How can we capture the manner in which these places remain behind, providing shelter when the noise of all this searching becomes too confusing, or the feeling of strangeness experienced when we return and discover that everything we thought we understood about these places was merely a product of our wants and needs? How can we turn this realisation into a story, not for ourselves, but for the people who brought us to these places, people whom we loved and spurned, and whose lives are bound to ours in ways too complex for us to understand?

This key passage sets the tone for the whole book, the central concerns of which build on the investigations of Kouvaros’ previous monograph, The Old Greeks: Cinema, Photography, Migration (2018). The questions are posed with poetic grace, imbued with melancholy and regret, yet also strive for answers that transform our understanding of the existential and historical forces that shape who we are.

Kouvaros’ inquiring mind covers considerable terrain, assembling in the process a wide range of artistic and cultural practitioners, including filmmakers and video artists (Wim Wenders, John Conomos), novelists (Annie Ernaux, Philip Roth, Patrick Modiano, Italo Calvino), poets (Antigone Kefala, Rainer Maria Rilke), and photographers – not only established photographers like Georgia Metaxa, but anyone who has ever taken a photograph of someone simply because they are part of a family, a community, and for that reason alone are to be commemorated. Despite his breadth, Kouvaros is always mindful to find the sources that best articulate his themes. It is this care that saves the collection from the kind of showy eclecticism – diluting rather than enriching – that can dog cultural theory.

These various journeys to, and into, modernity and the migratory often follow the modes of biography and autobiography, particularly as embodied in the physical photograph. A case in point is his essay, ‘A Light from Before’, about the work of French Nobel Laureate Annie Ernaux, whose terse, confessional novels exemplify the personal reckoning mediated by history that so captures Kouvaros’ imagination. In this essay he tracks Ernaux’s father’s ascension from farm labourer to small café owner during the period between the World Wars. A key feature of Ernaux’s writing is the use of the photograph as a departure point for the treatment of key figures in her life, mainly close family members. She depicts them not only as individuals in their own right but also as members of their generation, as singular instances of a larger collectivity. These individual photographic subjects, captured in a moment of light, are aggregated into a vast intergenerational mosaic.

This is the historical period when the photograph carried, in many ways, if not a greater burden of emotional investment, then a pathos bound to a materiality and scarcity that the digital photograph of our era precludes. Kouvaros homes in beautifully on Ernaux’s slow gaze on these photographs of early twentieth-century modernity, a gaze that fights against disappearance. This notion of disappearance provokes Kouvaros’ searching meditations on loss, the passing of time, and how writing can work against its inevitability. In combining the seemingly disparate media of words and light, Ernaux’s writing practice, Kouvaros shows, presents a paradox, whereby the evanescence of the photographic archive – its material basis in chemicals and paper that are as vulnerable to ageing as the archival subjects – is rendered permanent through linguistic signification. Kouvaros’ analysis of Ernaux, by implication, helps up distinguish between the photograph of modernity and that of postmodernity – between, that is, the decaying modernist photograph of the studio, the lab, the considered pose and the standardised setting, and the postmodern photograph of the anywhere and anytime, of the digital network that is both eternal and precarious, of the spontaneous that is both staged and authentic.

Disappearance and patrimony are also investigated in a context closer to home in essays where Kouvaros delves into his own Greek identity. In the collection’s introduction and first three essays, we enter Kouvaros’ personal archive of mid-twentieth-century photographs, and learn of a family, including the young George, that migrated from Cyprus in the 1960s. This is the Australia of Nino Culotta’s They’re a Weird Mob, of ‘new Australians’, of the assimilationist assumption that migrants had, in coming to Australia, made a pact: they would forfeit, at least outwardly, the culture they had left behind for the privilege of adopting the identity of this then far-flung corner of the Anglosphere, and their children would be fully signed-up members of a cult of mateship and the fair go, the mythos of what Donald Horne would dub, ironically, The Lucky Country (1964).

What is admirable in Kouvaros’ personal essays is how they rise above what was for many migrants an embittering, even degrading, experience. His are essays of resilience and dignity, of secret hope and quiet sacrifice. The theme of generational sacrifice looms particularly large. In ‘The Bouquet’, his parents’ long marriage is celebrated at a community event in a testimony to not only enduring commitment, but survival and, indeed, prosperity. Through decades of hard work in the family snack bar/kiosk, through working second jobs, they have succeeded in launching their offspring, giving them their best shot at joining a club they know they will never belong to: the middle class.

It is mainly in ‘Pacific Park’ that we see this narrative unfold. The young George is clearly smart, industrious, and, despite the usual missteps of a young person of talent, determined to succeed. We meet him as an adolescent, where, when he is not studying, he is working at his parents’ kiosk at Pacific Park, an inner-city beachside development in Newcastle. As he serves up chips and ice cream to the weekend crowds, he keenly feels the debt to his parents’ sacrifice, to their long, monotonous hours behind the counter, the endless toil that makes his future success possible. He makes us feel the stubborn resistance of a generation of migrants whose hopes for themselves may have been abandoned, but whose ability to hope ardently lived on in their children. The pathos of this narrative is rendered succinctly and with subtle wit in a photograph of the teenage George, his short hair neatly trimmed, his face resting in his hands in a pose of youthful mock-ennui, shot against a giant poster of a Pluto Pup that rears up on the wall behind him, its head dipped in sauce. The boy who gazes out at us will, decades later, be a successful academic, repaying the debt, acknowledging the patrimony in the way he knows best: by writing against the disappearance of his parents’ sacrifice.

It's only fitting that a book which engages with photography so intimately should construct itself as a mirroring of gazes. Another exercise in the gaze upon the gaze, ‘The Keys to the House’, provides an analysis of the work of recently deceased Greek-Australian artist John Conomos. His short experimental film, The Girl from the Sea (2018), depicts an aged Conomos sitting at the kitchen table in his recently deceased mother’s near-empty house, poring over the photographs of his family’s past spread out before him. Kouvaros’ essay delicately renders an almost unbearably poignant meditation on maternal love. ‘I’ve tried, in my stumbling way,’ narrates Conomos in his film’s closing moment, ‘to conjure you up from the depths of the past’. And conjure her up he does: a woman whose commitment to homemaking, whose vitality and spirit, provided the foundation for her family’s lives. In The Girl from the Sea, Kouvaros sees another act of resistance against disappearance:

[I]t is not the generalities of his mother’s life that Conomos endeavours to convey. Rather, it is her personhood and how this was expressed in an all-encompassing labour of homemaking – as a vocation, a duty, an act of love. To have been the beneficiary of this is the filmmaker’s privilege. To find the creative language to commemorate its passing is his obligation.

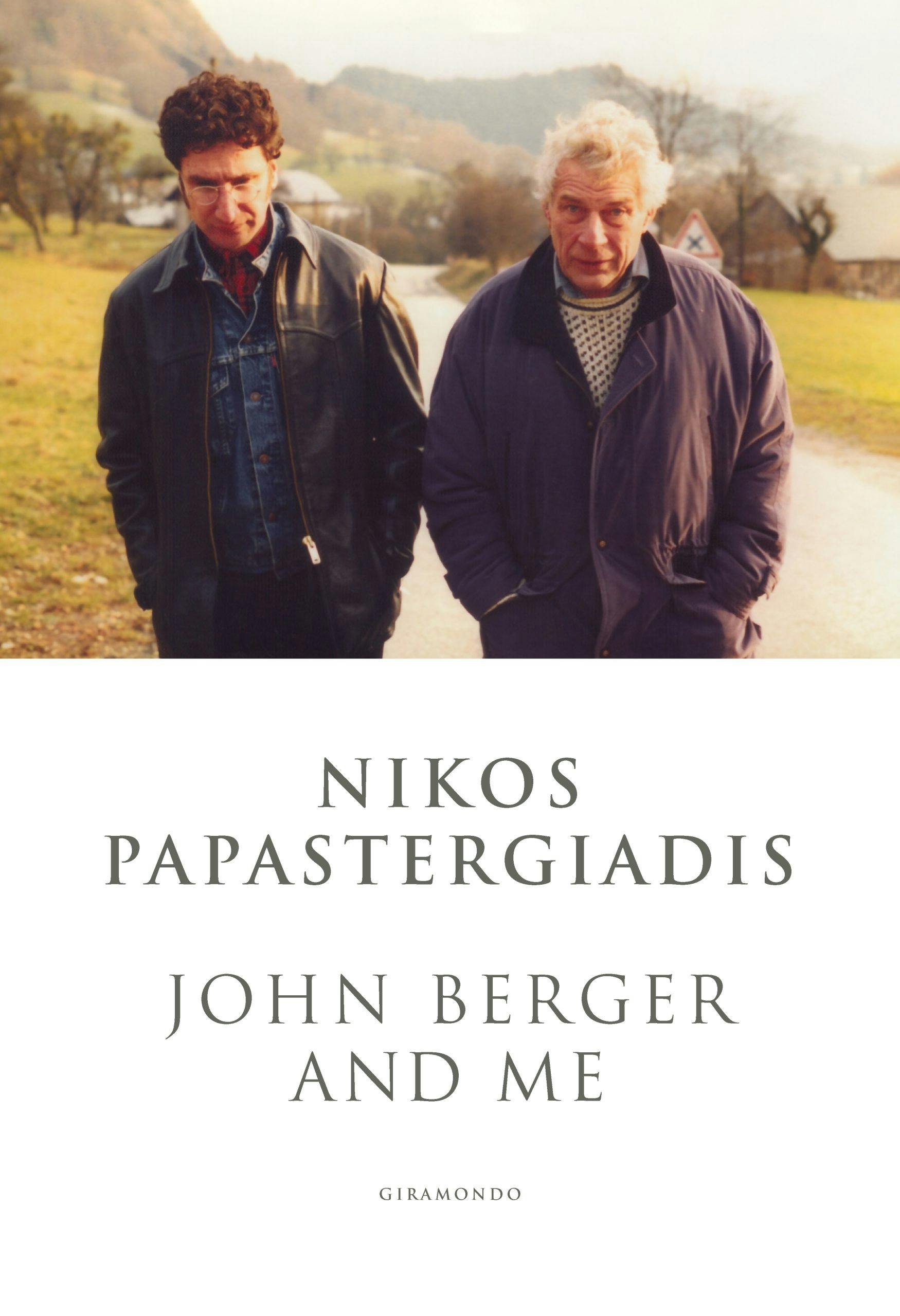

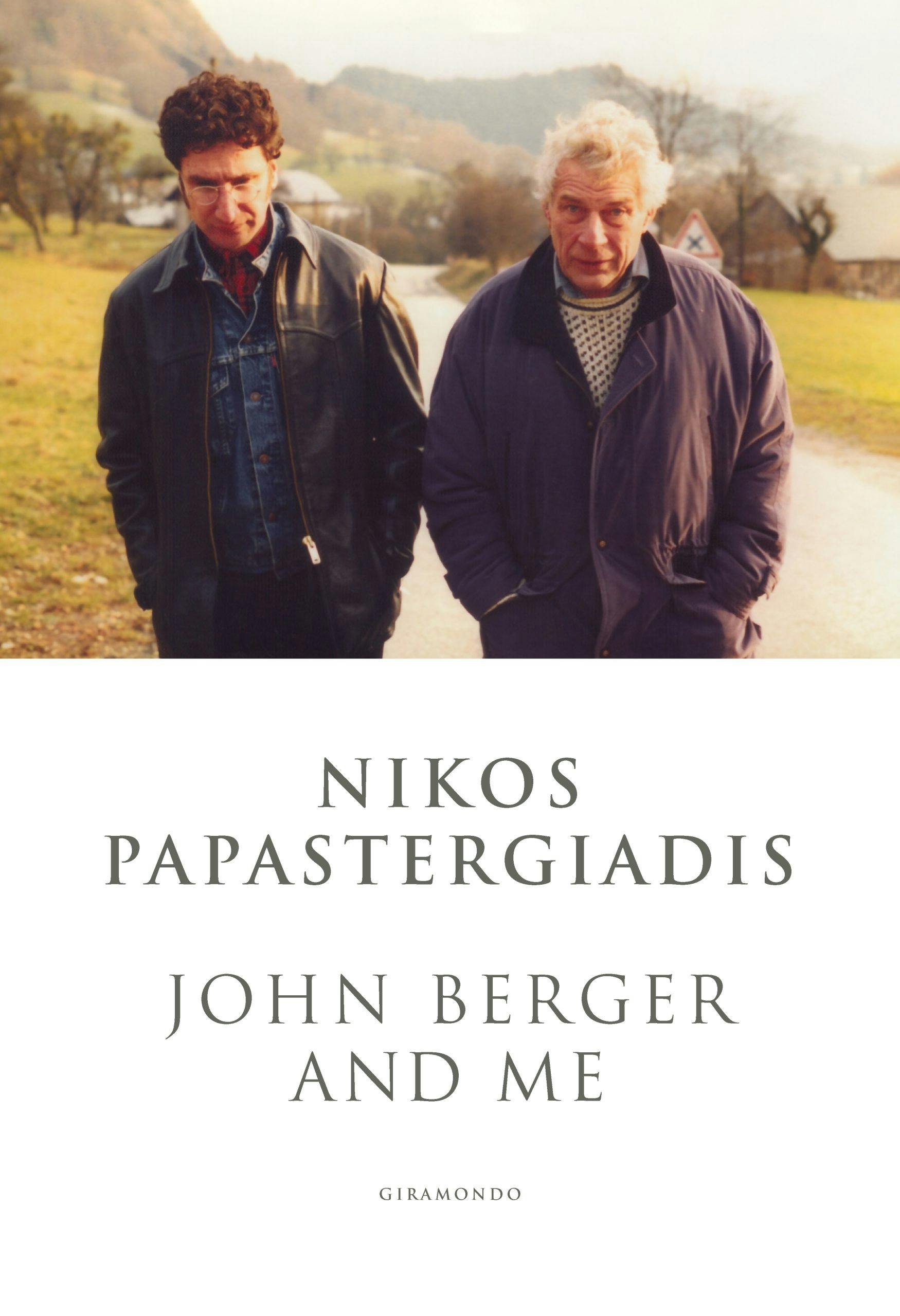

Migration, modernity, how we become who we become: in his memoir John Berger and Me, Nikos Papastergiadis shares thematic concerns with Kouvaros, using the framework of his long-standing friendship with the late John Berger to examine a critical period in his own life, while placing his friend within a broader cultural and social context. Ranging across his intellectual interests, from cosmopolitanism and migration to cultural theory and the visual arts, Papastergiadis employs biographical modes to extend themes he has explored in studies such as Modernity as Exile (1993), The Turbulence of Migration (2000), and Art and Friendship (2020).

In John Berger and Me, Papastergiadis provides a moving account of his friendship with Berger, the British art critic, broadcaster, and novelist who first came to prominence in 1972 with the ground-breaking BBC television series, Ways of Seeing, which was later adapted into a book. It is easy to forget the extent to which Ways of Seeing was a global phenomenon. I well remember it being on the syllabus when I attended art school in the late 1970s, where it was held up as the gold standard of how we should think about art. Considered fresh and exciting, it succeeded as a radical break from the kind of commentaries found in Thames & Hudson artist monographs that filled our college’s small library, and which were largely concerned with biographical and historical contexts, themes, and materials. Instead, clearly influenced by, or intersecting with, what would soon become Cultural Studies, Ways of Seeing – via some heavy borrowing from Walter Benjamin – discussed how the act of perception was situated in the politics of class and gender, as well as how technology and social power influence the way art was made and consumed.

It is this Berger – riding high on acclaim, at the intellectual cutting edge – that catches the interest of a young doctoral student from Melbourne, who has secured a scholarship to Cambridge. After a few false starts, Papastergiadis settles on the work of Berger as the topic of his thesis, and in the years after the completion of his studies, mainly throughout the 1990s, Papastergiadis regularly visits Berger at the latter’s home in the French village of Quincy. Decades later, in John Berger and Me, Papastergiadis has decided to write an account of this time and subsequent years, including Berger’s death, from the perspective of an established scholar, whose expertise on migration, cosmopolitanism, and aesthetics provides a comprehensive framework to explicate Berger’s worldview, as both a thinker and man. Moreover, Papastergiadis’ maturation as a teacher and father allows him to adopt a peer’s perspective on a friendship between men from vastly differing generations and backgrounds – one born in 1920s London, the Oxford-educated son of a military officer, and the other born in 1960s Australia, the son of Greek peasants – bonded by intellectual interests. Theirs is a multi-layered relationship: mentor and mentee, but also, in the parallel universe of Papastergiadis’ imagining, father and son, with Berger playing a paternal figure in a family romance where Papastergiadis, as an emerging academic, begins to rub shoulders with major intellectuals in Europe and the United Kingdom.

Papastergiadis handles the genre-hopping between theoretical reflection, memoir, and biography with considerable skill, showing himself to be versatile and entertaining. One of his main goals is to give us an insight into Berger’s day-to-day existence, as well as the texture of his personal and inner life. Indeed, Berger was also something of an iconoclast in his choice of how to live. Despite his privileged background and overnight success (he also won the 1972 Booker Prize for his novel G.), Berger moved to the French countryside where he enjoyed being surrounded by the simplicity of peasant life. He went on to maintain a life-long interest in the history and fate of the European peasantry as they entered their inevitable twilight in the last quarter of the twentieth century. In their plight, he found the theme of his celebrated ‘Into Their Labours’ trilogy of novels: Pig Earth (1979), Lilac and Flag (1987), and Europa (1990).

We find that Berger is accepted in his adopted village of Quincy, known and liked by his neighbours, and is determined to be more than the kind of all-too-familiar British expat who cherry-picks the parts of a foreign culture that give easy pleasure. A case in point is Berger’s willingness to participate in decidedly unglamourous annual haymaking, heavy work that takes skill, extensive local knowledge, and great stamina. Papastergiadis, who also willingly pitches in, takes great care to depict the haymaking through all its stages, and displays a novelist’s skill in bringing to life the pleasures of rural existence:

The midday sun is doing its furnace work. Louis has turned the cut grass. It is becoming juicy and crisp. The golden part of the afternoon is about to commence. The shadows start to stretch. The sun dips into a copper colour. The valley cools. The greens become subdued by the creeping blue-black evening. At the end of the day, we will slip down the hill, shower and prepare our evening feast.

This elegantly drawn tableau provides a lyrical celebration of these age-old farming practices, and evokes Georges Rouquier’s 1946 film Farrebique, which depicts the fast-vanishing rural existence at a French farm over four seasons.

We also learn that Berger is something of a city-phobe who can’t get in and out of a major capital – or anywhere with too many shops for that matter – fast enough, sometimes on his motorbike (‘always the latest and fastest Honda’). This love of motorbike riding is shared by the young Papastergiadis, and there are entertaining scenes where he and Berger not only ride through the French countryside, but also zoom across Europe, both enjoying the speed and exhilaration motorbikes afford. While the motorbike riding serves the book’s narrative dimension, it also has larger thematic implications: the co-existence of the modern and the pre-modern, or, to be more specific, the clash of a classic motif of modernity – speed and individual freedom – with that of the slow-paced, pre-industrial life of the village. Berger may be keen on proving his salt-of-the earth credentials, but his (Futurist?) love of burning up the motorway might be thought to expose him to the criticism of wanting a peasant life as long as it comes with mod cons. It’s easy to take pot shots at Berger for a bourgeois romanticising of the pre-capitalist past (the entire genre of pastoral is built on it), but thinkers from Trotsky to Bloch have refused such either/or-ism, pointing out that different epochs of technological, economic, cultural development co-exist in any given social formation, and that such unions of opposites can be the rule rather than the exception. Also, from a contemporary perspective where there has been significant re-evaluation of traditional and indigenous knowledges in the face of the environmental destruction wrought by unchecked ‘progress’, Berger’s desire to return to ways of living more in harmony with nature can be seen as prescient rather than dated.

While John Berger and Me provides an intimate portrait of Berger, the book is also about Papastergiadis, a kind of Portrait of the Academic as a Young Man, with their friendship providing both springboard and frame for Papastergiadis’ reflections on his own life. We learn of his upbringing in Melbourne’s Greek community, his intellectual development as a young scholar, his desire to eventually return to Australia despite having the choice of pursuing a rewarding academic career in Europe. Even when giving centre stage to Berger, Papastergiadis allows us to observe him observing Berger in a self-portrait at one remove that reveals its own particular truth.

If the European peasantry was Berger’s point of arrival, it is Papastergiadis’ point of departure. An important thread in the latter’s autobiographical reflections concerns the fate of men like his own father, who were caught up in the great transition of Greece from agrarian life – often subsistence farming – to modernity. In his youth, Papastergiadis’ father was a shepherd: during World War Two his job was to ‘hide the neighbour’s flock from the occupying Nazi forces’. Later, in Melbourne, he works as a guillotine operator in a printery. But a loving, diligent father (and his father is nothing less than this) is always a good role model, even if there are limits to the possible futures he can enable his son to see. This is one powerful reason Papastergiadis is drawn to Berger: he provides that vision of a future self. And not only a future self, but perhaps also an answer to the deep conundrum of how to reconcile the pre-modern and the modern, the Greek diaspora of Australia, with its origins in a rural past, and the scholar and thinker he knows he must become. Addressing Berger in the second person, as if he were writing him a letter, Papastergiadis tells him:

At the point in life when most successful authors look for comfort you found another life in a peasant village. You arrived in a place akin to the place which my parents had left. You were a prominent critic and celebrated author. I dreamed of the life you had lived.

But there is no suggestion that Papastergiadis, despite having acquired this glittering new friend, considers his own father a lesser being. The respect and regard he holds for him is heartfelt, and his depiction of his father’s death from Alzheimer’s disease is deeply moving. Rather, the point of his comparisons between these two father figures is, at least in part I think, to draw our attention to the great social transformations of the twentieth century that allow a son of Greek peasants to embark upon a life of the word, of the mind, all under the aegis of progress and modernity.

But progress has its price, and it is the disappearance of the peasantry that weighs heavily on the minds of both Papastergiadis and Berger. Reflecting on this, Papastergiadis returns to Berger’s Pig Earth:

For a century and a half now the tenacious ability of peasants to survive has confounded administrators and theorists. Today it can still be said that the majority in the world are peasants. Yet this fact masks a more significant one. For the first time ever it is possible that the class of survivors may not survive. Within a century there may be no more peasants. In Western Europe, if the plans work out as the economic planners have foreseen, there will be no more peasants within twenty-five years …

For Papastergiadis, Berger’s 1979 prognosis was unerring. In a passage that exemplifies the way he relates the personal to the historical, the individual to society, the old to the new, Papastergiadis writes:

By the turn of the twenty-first century all the [French] peasants were gone. My parents had moved from their peasant villages in Greece and become proletarians in the factories of Australia. Their ‘class’, which had ‘survived’ thousands of years of imperial domination, religious wars, feudalism and colonisation, was now finally wiped out. Modernity, with the appeal of labour-saving devices and individual progress, erased the need for peasants.

And it is his father, one of these peasants who has undergone such an erasure, who seems to haunt Papastergiadis. The portrait that Papastergiadis provides of him is woven into the fabric of his narrative in ‘a helix-like’ manner’ – sometimes occasioned by a Proustian, sensory trigger related to a physical aspect of Berger, at other times as part of a shadow narrative to the central Berger story. Like so many post-war Greek migrants to Australia, Papastergiadis’ father, despite becoming an urban worker or ‘proletarian’, maintains his rural identity by doing what so many village Greeks of his generation did: growing his own vegetables for his family. These scenes of cultivation, of knowing when to plant and harvest, how much water to use, bespeak a vast knowledge built up over generations. Papastergiadis’ father transplants this knowledge to a completely different context of a suburban backyard in Melbourne. It’s a telling image of the waning of the European peasantry, its absorption by the inexorable process of modernity, one put into action by the migrant themselves when they decided, often under duress, to exchange one life for another.

In the received version of Australia’s history, one can get the impression that Greeks only arrived in Australia in the 1950s and 60s, largely due to World War Two and, immediately following, the Greek Civil War. Greeks have, in fact, been coming to Australia since the early nineteenth century, at first in a trickle, but one that picked up speed in accordance with various historical events: notably the gold rush of the 1850s, the Balkan Wars (1912-1913), World War One (1914-1918), the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922), and the Greek Genocide (1913-1923). My own maternal forebears, from the island of Kythera, are said to have started coming to Queensland in the 1890s, for reasons that are lost in time.

It’s in this way that the Greek diaspora in Australia – an implicit sub-theme that runs through both Kouvaros’ and Papastergiadis’ books – was formed. Their richly nuanced meditations on the Greeks in Australia provide us with a multi-perspectival understanding of its unique nature. In bridging the scholarly and the personal, the cultural and historical, and much else besides, they have extended the community’s story beyond the often-sanitised tropes of migrant struggle – tropes that, while relating all-important aspects of the migrant experience, risk losing any meaningful impact due to their quaint stereotyping of Greek culture for mainstream Australian consumption. Certainly, the Greek diaspora we encounter here, at least for an older generation, is one of personal sacrifice, isolation, and cultural alienation, a world of modest dwellings and long hours of menial labour. However, by sharing their own lived experience and that of Greek Australian artists, then situating these experiences in complex layers of history, feeling, and ethical ambivalence, Kouvaros and Papastergiadis render the Greek diaspora in Australia with a rare vividness and depth.

Doing justice to these two books has been a challenging task, partially because of their thematic scope and ambition which extends beyond, without ever losing sight of, these local autobiographical contexts. If I have emphasised modernity and migration as central themes at the cost of others, it is because I believe that they are themes that can capture, with at least some comprehensiveness, one important part of what they are trying to achieve. There are many ways we can think of modernity. We can think of it in philosophical terms, according to Marshall Berman’s Marxist conceptualisation, as a moment characterised by its ability to create and destroy. We can think of it in grand historical terms as the democratic triumph over autocracy signalled by the French Revolution (which was quickly followed by the 1821 revolution that saw Greece liberated from Ottoman rule). We can think of it in industrial terms as the proletarianisation of the peasant workforce in the reforms of the Soviet Union in the 1920s or in China in the 1950s. And we can think of it in personal terms, as do Kouvaros and Papastergiadis, through the photographs of lost eras, through a friendship with a major art critic holed up in his French village, or through the meditations on parents who have journeyed, in one lifetime, from the pre- to the post-industrial. All these aspects of modernity co-exist to some degree, each a lens through which to comprehend world-making and world-breaking transformations. It is the achievement of both Kouvaros’ and Papastergiadis’ books that they show how such transformations take place, how the individual is mediated by society, and how their individual stories form part of a bigger story that spans cultures, continents, and centuries.