I

‘They gave me your things in a brown paper bag. I asked to see you, to be convinced that what they were telling me was true.’ What ‘they’ – the doctors and nurses – were telling the narrator in Antigone Kefala’s novella ‘Conversations With Mother’ is summed up in three short words: ‘You had died.’ Perhaps it’s because she had assumed that the worst had passed and that things were looking up for her ailing mother that the narrator finds this so hard to believe and why she needs to see the body, for herself: ‘And there you were behind the glass, on this trolley, in white, with your white hair, I scaled the steps and went behind the glass to see you, touch you, stroke your forehead, your hair.’ The situation of a narrator addressing an absent loved one is far from unusual. In Kefala’s rendition of this familiar trope grief crosses paths with indignation and disbelief. ‘I have written to everyone about your death,’ she tells her mother, ‘so that all of us can be up in arms about it.’ It’s one thing to accept the death of a loved one, the narrator’s indignation suggests. It’s another thing entirely to accept her disappearance. ‘I was telling Elizabeth over lunch: ‘No, no, I shall never accept this disappearance, whatever they say . . . everyone says . . . however inevitable . . . no . . .’’ The challenge that drives the narrator’s reflections can be put quite simply: how to render the impact of this disappearance on a world that has been lessened by her mother’s death, stripped of an essential dimension, at the same time as it has become strangely enlivened by the shock waves generated by this terrible event. ‘Saturday night in Paramatta Road, the darkness of the night, the lights in the park, the terrible idea that you had disappeared for ever took my breath away, a terrible knowledge that had gathered for a second in the feeble lights across the street, the empty blackness of the night.’

II

‘When a person dies,’ writes John Berger, ‘they leave behind, for those who knew them, an emptiness, a space: the space has contours and is different for each person mourned. This space with its contours is the person’s likeness and is what the artist searches for when making a living portrait.’ The matter I want to pursue is: how are the terms and conditions of this likeness reconfigured when the portrait is filmic rather than literary? What elements give the filmic portrait its distinctive engagement with the disappeared? For all its capacity to bring the world closer to us, film’s greatest strength may be its ability to render a looming absence. Early in John Conomos’ video The Girl From the Sea (2018) we observe the director sitting at a large dining table scrutinizing a selection of black and white photographs of his late mother, Maria. The photographs illustrate some of the biographical details described in his voice-over narration: her arrival in Australia from Kythera as a girl of eleven or twelve, accompanied by her two sisters; her time spent living with her aunts in the NSW towns of Warialda and Inverell; her marriage to George, the director’s father, and their life together running a milkbar in the Sydney suburb of Tempe; her devastation at his sudden early death and her subsequent marriage to Zacharias. The director also recounts the illnesses that plagued his mother’s later years and his own attempts to break through her ‘encroaching Alzheimer’s muteness.’

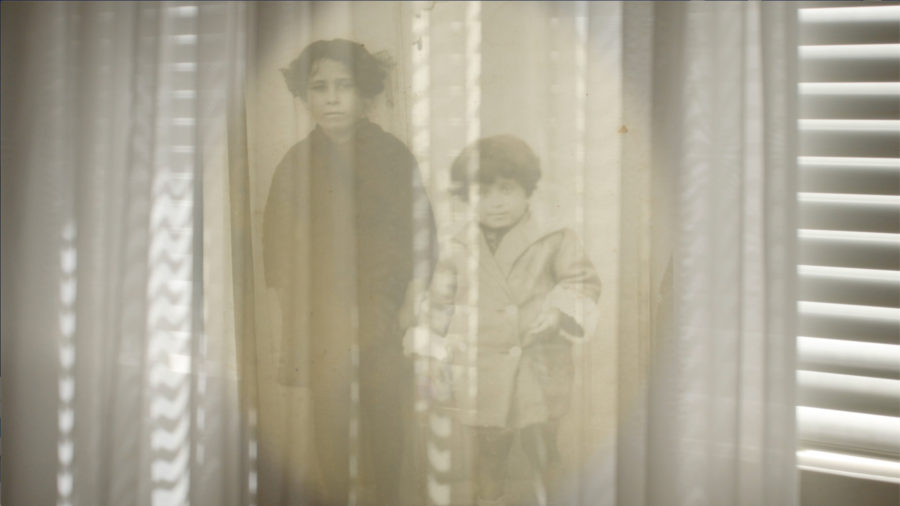

These details furnish the outlines of a life that resembled so many other lives that were part of the great waves of human migration that took place in the years leading up to and immediately following the second world war. But it is not the generalities of his mother’s life that Conomos endeavors to convey. Rather, it is her personhood and how this was expressed in an all-encompassing labour of homemaking. Homemaking as a vocation, a duty, an act of love. To have been the beneficiary of this is the filmmaker’s privilege. To find the creative language to commemorate its passing is his obligation. This is to say that the purpose of the photographs is to drive a work of remembrance in which the presence of the magnifying glass in the director’s hand acts as a proxy for the camera’s investigations of these images. The slow zooms into the photographs that spotlight a certain detail or facial expression; the panning movements across the surface of the black and white prints that bring the past into an engagement with the present; the dissolves that establish a relationship between two or more images: these are some of the ways in which the camera functions as an extension of the director’s gaze and approaches the residues of his mother’s past through its own distinctive ways of seeing.

In the opening shot the camera guides the spectator through the front garden of the family home in Hurstville. Once inside the house, it peers into the almost-empty front bedroom. The dark wooden bedframe and mattress, stripped of sheets and blankets, are the vestiges of a life that, little-by-little, is losing its grip on this place. And for the next fifteen minutes or so, the camera will move in and out of these rooms, surveying the remaining pieces of furniture and gently billowing curtains and venetian blinds. Its scrutiny of these almost-empty rooms works in concert with the director’s voice-over to conjure a labour and a spirit that made them something greater than the sum of their parts. When the camera sweeps into the kitchen it considers a collection of keys spread across the benchtop. Their sheer number poses a challenge to the mind. What do these keys open, one wonders? To what tasks do they belong? Elevated above their station by the camera’s close-up observation, they remind us of cinema’s capacity to reveal elements of everyday life that are usually overlooked or excluded and, at the same time, bring about a productive estrangement. Guided by the camera’s way of seeing, we approach the world not from above, as Siegfried Kracauer so memorably observes, but from ‘under the table.’

Now if this is true of the camera’s rendition of the world, generally, it is doubly so in the case of those films that take stock of a home-space. In Robert Frank’s Home Improvements (1985), for example, the video camera operates as an extension of the filmmaker’s roving eye as it moves through the world. The handheld shots of the artworks scattered around his studio; the footage of his partner, the artist June Leaf, inside their car watching the waves battering the foreshore near their home in Nova Scotia; the close-up shots of a fly moving along a windowpane: these sights and sounds evoke a fragile sense of happiness and provide the backdrop to Frank’s voice-over ruminations about those closest to him. After visiting his son, Pablo, in the psychiatric treatment center, Frank uses the video camera to record his troubled thoughts during the journey home: ‘As I walk back from the visit with Pablo . . . I always have hope, but I realise that . . . I would try. And I think it means a lot to him if I try. He knows when I try. I just don’t know how long I can do it.’ The jumpy footage of the nondescript hospital buildings and the moments when the filmmaker pauses to gather his thoughts ground the images in his physical and emotional state of being. They encapsulate a way of employing the video camera that Philippe Dubois describes as ‘a form of looking and thinking that functions continuously and as if live with everything.’ This is a view of the video camera as always present, always within easy reach of hand, eye and voice.

In Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie (2015) the camera also functions as an extension of the filmmaker’s eye as she moves through the rooms of her elderly mother’s apartment in Brussels. But at other times it remains resolutely fixed in place, observing and listening-in on the conversations between the director and her mother at the kitchen table. This positioning of the camera is also evident during those sequences when it takes up a spot in the lounge room or hallway and patiently observes the apartment’s occupants. During one such sequence the camera is stationed outside the partially opened door to a room that is bathed in light from a window in the background. Through the open door we can see the silhouette of the filmmaker’s mother, Natalia, and, once or twice, the filmmaker, herself. Here, as elsewhere in the film, the camera’s focus is on the person and the space around the person: its structures, impediments and quality of light. This dual focus locates the filmmaker’s portrait of her mother between two poles that have long been seen as essential to the form of viewing enabled by the camera: on the one hand, an acute feeling of proximity to the events and individuals portrayed on screen and, on the other, the impression of an unbridgeable distance, in time as much as in space. In Akerman’s film the interaction of these two poles conveys a sense of home as determined by the physical and emotional closeness of a parental bond between mother and daughter and as always-already lost.

III

In The Girl From the Sea the camera’s graceful, almost rhythmic, slow motion pans provide an inventory of what remains of Maria’s life and convey a powerful choreographic presence. This is no doubt aided by the inclusion on the soundtrack of the rise and fall of waves lapping the shore of an unseen beach. The incorporation of this audio element reminds us of Maria’s ancestral home on the island of Kythera. It also affirms that what Conomos is constructing in the video is two things, at once: home as an actual place made from bricks and mortar and home as an image, as something formed by the interaction of the material and the imagination. ‘Light, space, time, sounds, smells and memory all coalescing like a swirling iris of a kaleidoscope of our shared life-world together.’ This coalescence is given further force by the superimposition onto the gently billowing curtains of some of the photographs that were laid out on the dining room table as well as the inclusion of brief excerpts from films that stand-in for the director’s recollection of events that he either experienced directly or heard about second-hand. The first involves a story told by his mother’s cousin. It concerns Maria as a small child scrambling down the mountainside near her home village of Karavas. In the director’s mind, this story recalls Ingrid Bergman’s flight up the volcano in Roberto Rossellini’s Stromboli (1950). The second event involves the terrible day when the filmmaker witnessed his mother’s response to the phone call telling her of George’s death. The impact of this event is conveyed by the inclusion of the moment near the finale of Orson Welles’ The Lady From Shanghai (1947) of the staggering protagonist sliding into the mouth of an amusement park mechanical monster.

Based on the connections established between different images and between images and the memories they inspire, this method of appropriating images defines a process of artistic creation that uses the cinema to evoke a threshold – between documentary and fiction, past and present, memory and forgetting. ‘The idea is to create connections,’ Jean-Luc Godard explains. ‘Just as stars are drawn closer to one another, even as they move further away from one another, held together by physical laws, to form a constellation, certain thoughts are drawn closer together and form one or several images.’ The distinctive thing about Conomos’ approach is the way in which the connections formed speak to a gap in one’s knowledge that is a consequence of the displacements that accompany migration. Near the start of the multi-screen video installation Album Leaves (1999), for instance, he wanders through a graveyard looking for his father’s resting place – mumbling to himself as he moves along the rows. When he comes to the plot where his father, George, is buried his words suggest both relief and disappointment: ‘This is it here. . . .It’s not what I imagined it to be.’ His words trail off to be picked up at a later point. Looking down at his father’s grave, he muses: ‘It’s so hard to capture him . . . You never do, do you? You just chase your own shadows.’ These simple yet evocative words allude to everything that gets lost in the passage from one generation to the next, from one culture to the next. The restless never-finished engagement with images that defines Conomos’ method is, on one level at least, an attempt to compensate for this loss – a method of constructing knowledge in the face of its possible extinguishment.

IV

The other way to describe this endeavour is as an activity of homemaking. In an account of some of the changes that characterise the history of modernity, Berger contrasts an archaic notion of home, understood as a fixed centre that enables its inhabitants to maintain a sense of continuity between the past and the present, the living and the dead, to a more contemporary notion of home as something built from scratch. The instigator for this change is the large-scale migrations of people from village to city and from country to country that have occurred over the past two centuries. For those whose lives were reshaped by these migrations, the traditional notion of home as something predetermined is replaced by a structure built on the accretion of habit, repetition and, above all, memory. ‘The mortar which holds the improvised ‘home’ together – even for a child – is memory. Within it, visible, tangible mementoes are arranged – photos, trophies, souvenirs – but the roof and four walls which safeguard the lives within, these are invisible, intangible, and biographical.’

In The Girl From the Sea, Conomos’ agenda is two-fold: to recount the extraordinary spirit that marked his mother’s life and to safeguard the memories on which the home-space is founded. He tells us of his mother’s optimism, effervescence and will to live. He recalls her urgings that he be less lazy and more appreciative of life’s possibilities. He alludes to the scandal caused when she announced her intention to marry – too soon after George’s death in the eyes of friends and family – Zacharias as well as the fatalism and pathos conveyed by her singing of the Doris Day classic ‘Que sera, sera.’ Perhaps most poignantly of all he recounts her enthusiasm for collecting miniature porcelain figurines. Listening to his account of her passion for arranging these delicately wrought figures into scenes of an idealised domestic life one can hear a foretelling of Conomos’ own endeavours with images and sounds. The work of homemaking in which the filmmaker is engaged is thus not only about the creation of a continuity between past and present. It is also about the future – how we remember the person that we will become.

V

The concluding section of The Girl From the Sea begins with a shot of the filmmaker standing in front of the microphone reading from a script. Up to this point, his presence had been registered as a body hunched over the photographs spread across the dining room table or as a voice-over recounting the details of his mother’s life. Now we see him as someone who has reached a point in his life when the ailments and afflictions that marked his mother’s later years weigh heavily on his own existence. The issue, then, is age, not simply as the sum of so many years of existence, but also as a form of mutuality that binds our existence to the existence of those who came before. In The Girl From the Sea this mutuality is both a burden and a comfort. It foretells the travails that lie ahead and establishes continuity between the generations. In the concluding narration the filmmaker describes how, during the final years of his mother’s life, when renal failure and the gradual worsening of her Alzheimer’s disease made communication more and more difficult, they would sit together at Cronulla, Brighton Le Sands and San Souci and watch the ‘colourful bobbing seacraft.’ ‘What ensued between us then,’ he recalls, ‘was a kind of deeply felt monosyllabic form of Rogerian psychotherapy, a longing, an attempt to reanimate your being, your shared existence with mine.’

‘Everything I see, I hear, I remember, I touch, leads back to you,’ writes Kefala in ‘Conversations With Mother.’ ‘It does not matter how remote, how unconnected, how far, everything leads back.’ In Kefala’s novella the narrator projects her indignation and disbelief onto a world that must be held accountable for her mother’s disappearance. The trips to the movies or the theatre; the visits by friends who offer their support and bring with them their own troubles; the sudden change in the weather and its impact on the flowers in the garden: these events ground Kefala’s novella in the routines and interactions of daily existence. In the context of the narrator’s grief, they also suggest a world too ready to resume its flow. The end of the novella does not bring acceptance or an easing of this grief. Instead, the shift in tone stems from an image in which the indicators of time’s passing carry with them a suggestion of survival. Walking through Sydney’s Botanical Gardens, the narrator describes the trees as marked by a ‘human heaviness’: ‘The Moreton Bay figs with those heavy shapes made of granite, and the olive trees, full of little breasts coming out everywhere, as if a series of humans that have disappeared to leave only some vital part of their bodies transfixed into bark, to survive longer.’

In the concluding section of The Girl From the Sea the filmmaker also offers an image that recasts the feelings of loss associated with his mother’s death. Introduced during his account of the trips to the seashore with his mother, the image is of two sailing boats moving in opposite directions across an expanse of ocean. The purpose of this image is to illustrate the narrator’s account of the trips to the seashore as well as provide something that exceeds the capacities of the narration: a direct engagement with the world, its colour, energy and movement. The azure-coloured water and matching sky; the bright white billowing sails of the two boats; their slow-motion movement up and down and across the water: these elements distance us from the almost-empty rooms of the soon-to-be abandoned house. They mark the point at which the labour of homemaking, of creating a place where one might obtain shelter from the sudden turns-of-fate embodied by George’s death, coincides with a drive to venture forth and place oneself in the path of these blows. This is a conception of homemaking in which the accretion of habit, repetition and memory carries with it a responsiveness to the possibilities and as yet undetermined qualities of the present. The image of the two sailing boats making their way across the horizon is, thus, finally, a way to commemorate Maria’s passing and draw from the transitoriness and beauty of the visible world an image that captures what the filmmaker in his concluding words describes as her unique gift, the ‘gift of being vital to life, itself.’

The Girl From the Sea was acquired by the Art Gallery of NSW in 2019. It can be viewed on vimeo.

Works Cited

Berger, John. And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos (New York: Vintage International, 1991).

Berger, John. The Shape of a Pocket (London: Bloomsbury: 2002).

Dubois, Philippe. ‘Video Thinks What Cinema Creates: Notes on Jean-Luc Godard’s Work in Video and Television,’ in Jean-Luc Godard: Son + Image, 1974-1991, ed. Raymond Bellour with Mary Lea Bandy (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1992).

Godard, Jean-Luc and Miéville, Anne-Marie. The Old Place (Paris, P.O.L., 2000).

Kefala, Antigone. ‘Conversations With Mother,’ in Summer Visit: Three Novellas (Sydney: Giramondo: 2002).

Kracauer, Siegfried. Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997).