At one point many China women came to Singapore. Some are study mothers. Some are from unknown backgrounds. They used to operate from Chinatown and some hung around the rooftop garden of People’s Park market. They seduced old married Singaporean Chinese men and disappeared after cheating them of money. These old men after being cheated, lost their wife and children and ended up homeless and stranded on the streets. They sought help from the government but there were too many cases like that. In the end the government changed the law where the retirement funds’ withdrawal age became 65 years old instead of the original 55 years old, and limited the withdrawal amount where retirees could only have an instalment amount each month instead of withdrawing all of it and squandering or getting cheated by these women. This in the end caused so much troubles and harmed local Singaporean women.

The Fire Dragon, Between Myths and Realities

Quah Ee Ling on the uses of the fire dragon for feminist critique

Quah Ee Ling charts the changing connotations of the term ‘dragon lady’ from its provenance in Buddhist sutras onwards, exposing in the process the ethno-cultural and gendered myths that have shaped the life stories of Asian women migrants.

The following is an extract from Quah Ee Ling’s monograph, Fire Dragon Feminism: Asian Migrant Women’s Tales of Migration, Coloniality and Racial Capitalism, published open-access by Bloomsbury Academic. The book will be launched as part of the Writing and Society Research Centre’s seminar series on Friday, July 25.

Asian migrant women have been associated and perplexed with multiple imageries of inspiring and as well as, disparaging meanings unfortunately. The term ‘dragon lady’ has commonly been associated with portrayal of Asian women in popular Hollywood movies as scheming and ruthless and even landed with a definition of ‘an overbearing and tyrannical woman’ in the 1996 Meriam-Webster’s dictionary. Contributing to the overall Orientalist discourse of Yellow Peril in European, Northern American and Australian settler-colonial societies as early as 1800s, lasting till today with recent Covid-19 pandemic-related anti-Asian racism in 2020–2, the Dragon Lady symbolizing Asian migrant women has been described as yet another evil from the East responsible for contaminating their good white society. It is however important to note that ‘Dragon Lady’ bears different meanings and symbolic purposes for different people and communities beyond being the dominant derogatory symbol of Oriental debauchery.

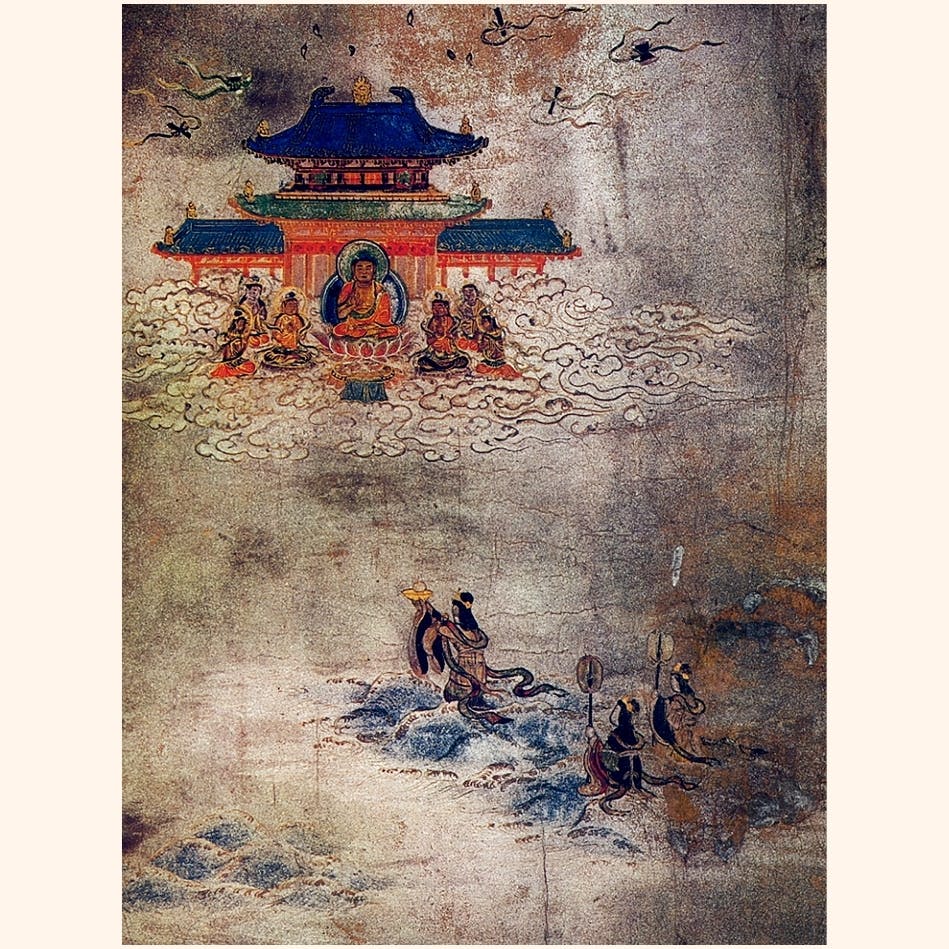

For example, 龙女, directly translated as Dragon Woman or Dragon Lady, features significantly in a major branch of Buddhism, Mahayana Buddhism. In Lotus Sutra, a key scripture of Mahayana Buddhism, its Devadatta chapter or chapter 12 describes 龙女 as an extraordinary eight-year-old daughter of the dragon king and references 龙女 as Dragon Princess or Dragon Daughter though the term directly translates to Dragon Woman or Dragon Lady. The Lotus Sutra records that 龙女, Dragon Princess or Dragon Daughter, attained enlightenment after presenting a legendary pearl to Buddha on behalf of her dragon king father (see Figure 2.1). She is celebrated for her extraordinary wisdom and enlightenment in arriving Buddhahood or Bodhi at such a young age. It is interesting to note that the Lotus Sutra also records the strong objections 龙女 faced in her attempt to attain Buddhahood. Her opposers argued that ‘a woman’s body is soiled and thus cannot serve as a vessel to advance the Mahayana’, and a woman herself would also face ‘五障 five obstructions’ to achieve enlightenment. The scriptures, however, write that Buddha intervenes and affirms 龙女’s attainment. Her story becomes a reminder that women can become buddhas too. While the scriptures indicate that Buddha objected to patriarchal notions where women’s bodies are tainted and could not attain Buddhahood and proceeded to give 龙女 a seal of approval, the parable in the end reconciles with patriarchal values by including an important detail that 龙女 rebirthed as a man to achieve the highest level of Buddhahood. The message here is that women can become buddha but in order to reach a level comparable with Buddha, they need to become a man first. This is a profound yet typical discovery on 龙女’s myths. The legend relates women’s entanglements with constrictive obstacles patriarchy presents, their attempts to break free of such chokeholds and somehow inescapable conformity with men’s rules to achieve the highest form of success.

Figure 2.1 Sutra art from the Heike-Nôkyô; the mikaeshi of chapter 12, Lotus Sutra. Image Credit: Culture Japonaise

Transnational flow of Buddhism, Buddhist scriptures and Indian Buddhist literatures from India to China brought about proliferation of Indian-Chinese folklores and literary works on the dragon king and dragon girl or daughter or princess. What followed was the metamorphosis of Indian Buddhist’s Dragon Lady into a wide variety of Chinese literary works dated as early as Six Dynasties (ad 220–589) and reaching its peak in Tang Dynasty (ad 618–690; 705–907). This body of Chinese literatures took on the Lotus Sutra’s characterization of 龙女 Dragon Lady as a woman warrior of extraordinary bravery, wisdom and divine power and fused it with local historical, cultural and social contexts and folklores to produce many more adaptations. What is interesting to note is that the interactions between Indian-Buddhism and Chinese societies inspired the embodiment of transnational and intercultural interactions in the development of mixed-race Dragon Lady characterization in Chinese literary works during these periods of Chinese dynasties.

Remarkably, Chinese societies’ fascination with Dragon Lady endures through centuries and continues to populate print and screen media in contemporary times. In particular, a Chinese martial arts novel, 神雕侠侣 The return of the condor heroes, published in 1959 by well-known People’s Republic of China (PRC)-born, Hong Kong-based writer 金庸 Jin Yong features a prominent fictional character (see Figure 2.2) and has been adapted into multiple popular drama series over several decades in Hong Kong, PRC and Singapore. In this widely known story across Chinese societies, 小龙女 is an esteemed, highly skilled martial arts warrior. At the age of fourteen, she assumed leadership of the martial arts sect who adopted her when she was abandoned on the street at birth. She was named 小龙女 after the Chinese zodiac year of dragon she was born in. Here again, Dragon Lady is portrayed as an extraordinary woman warrior who displays exceptional talents and leadership qualities at a young age, akin to the dragon maiden mentioned in the Lotus Sutra.

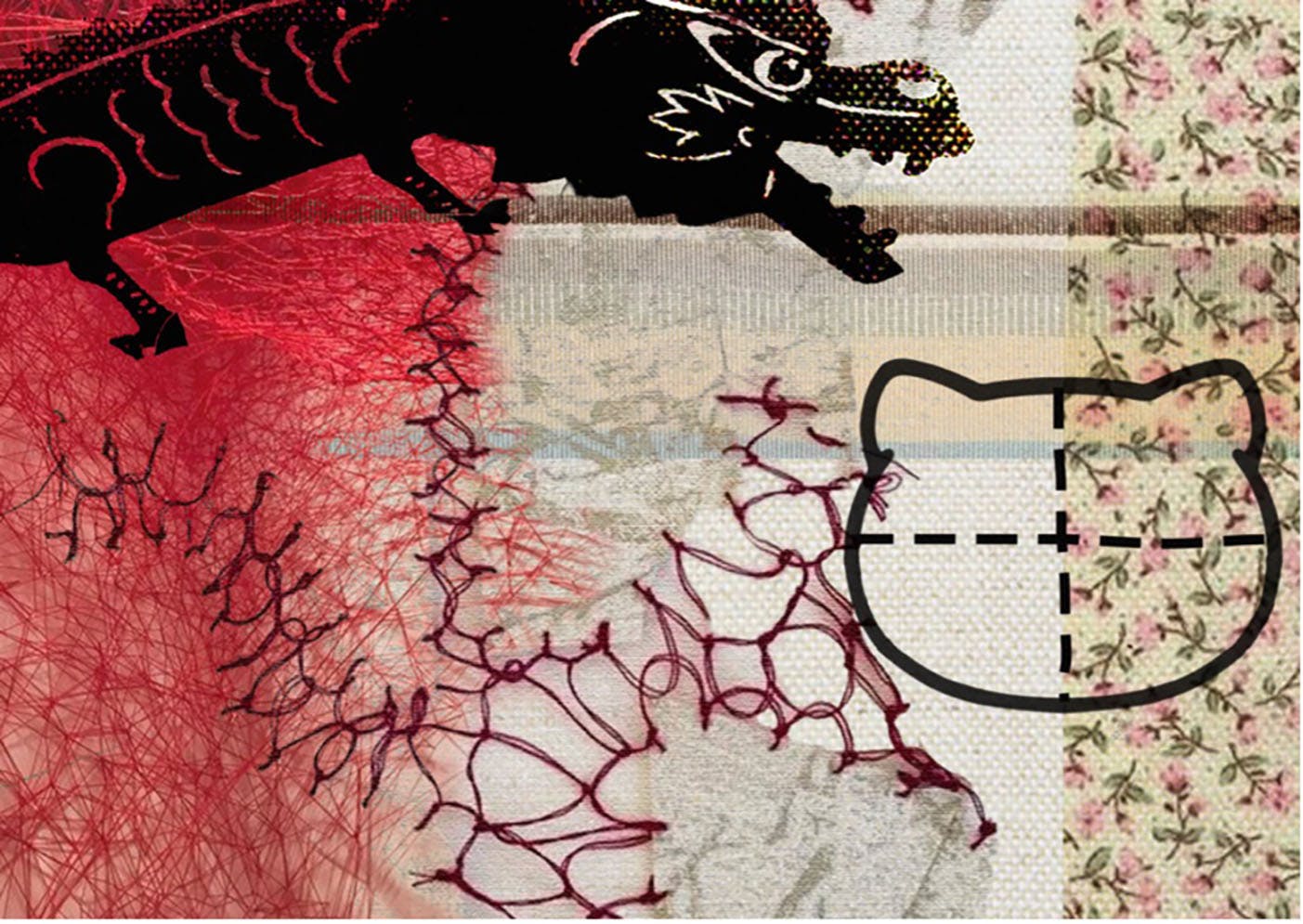

Figure 2.2 Artistic visualization of Fire Dragon Feminism by visual artist, Yanti Peng, a Metal Dragon Chinese first-generation immigrant in Australia. Image Credit: Yanti Peng

What is noteworthy in this popular novel is that the author, 金庸 Jin Yong, chose to centre 小龙女, his lead woman character’s romantic relationship with her younger male disciple. Not only is the master-disciple romance a taboo in the martial arts community during the period the novel is set in, but also the feature of intimate relationship between an older woman and a younger man would have also been trailblazing in Chinese societies at the time the story was written and published. Both characterizations of 龙女 Dragon Lady in the early Indian Buddhist scriptures and contemporary Chinese literary works call attention to the women’s queering of dominant standards imposed on women in specific contexts they are located in and their extraordinary feats in breaking free of constrictive patriarchal and heteronormative structures. Both Dragon Lady legends leave behind deep cultural imprints of feminine attributes and woman warriorship in popular imaginations across Asian societies. However, at the same time, both dragon women stories sharply reveal the ways in which deeply entrenched systems of patriarchy, sexism and misogyny control and restrict women in their respective contexts and times.

For the past two decades, the image of Dragon Lady has unfortunately come to bear deprecating connotations. In early 2000s, derogatory cultural references of 小龙女 Little Dragon Woman emerged in Southeast Asian societies such as Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand. The negative label was given to PRC-born women sex workers engaged in illegal sex work at nightclubs, karaoke bars and brothels. Other disparaging terms such as 乌鸦 Crow; China Girl; 中国妹 China Sister; and 中国娃娃 China Doll were also added to the anti-PRC Chinese women racist lexicon in these Southeast Asian-ethnic Chinese societies. These names carry a persistent xenophobic, racist and sexist subtext that PRC-born women are money-grabbing and have infiltrated Southeast Asian societies to extract money from local men, wreck families and create havoc in otherwise peaceful and stable societies. Widespread inflammatory accounts on how PRC-born Chinese immigrant women destroy marriages by being a mistress or ‘第三者 the third party’ in extramarital affairs; work illegally as sex workers and get rounded up in police raids at bars and nightclubs; enter sham marriages for permanent residency and citizenship and cheat their citizen husband of money before dumping them for another man; find themselves a sugar daddy or work as an escort while on a student’s visa; and seek work as a masseur that provides additional sex service for extra cash while being on a student guardian or long-term social visit visa as a 陪读妈妈 study mother or parental guardian for their school-going child circulate widely in mainstream and social media. My 姨姨 youngest maternal aunty, one of the important interlocuters of this study, has gathered decades of stories and insights from her workplace as a retail assistant, patronage at local bars and ‘咖啡店 kopitiams’ (colloquial term in Hokkien dialect for local coffee shops in Singapore) and consumption of everyday mainstream and tabloid news. She related this when I asked her about the cultural reference of 小龙女:

Interestingly, the local sentiments revealed resentment towards Chinese foreign women and saw them as threats and ills, while local citizen men came out blameless and seen as the innocent, gullible victims.

Such xenophobic sentiments about Asian foreign women and marriage migrant women extend beyond PRC Chinese women to other migrant women from less wealthy countries in the region such as Malaysia, Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand. The prejudiced discourse against lower-income Asian migrant women is certainly not unique in Singaporean society but also in other wealthier migrant- receiving countries. In my previous study on marriage migrant women, transnational families and divorce, I have also shown how such racist and xenophobic notions about foreign women from less wealthy countries out to cheat, plunder and extract resources from hardworking, unsuspecting men and families of their wealthier host society seep right into seemingly neutral and rational official immigration and family policies to ‘protect’ local populations and safeguard national resources. Specific marriage, family, immigration and retirement funds policies have been developed and implemented based largely on nationalistic, xenophobic and paternalistic beliefs that good, honest local citizen men must be protected from foreign, conniving women from less wealthy countries. It is not hard to observe that seditious portrayals in both popular and official discourses impact the migration experience of Chinese immigrant women where blows of xenophobia and racism hurled against them in insidious and overt ways affect every aspect of their settlement including employability, work, housing access, living conditions and social relationships. Some nightlife businesses even went to the extent of putting up signs at the entrance and disallowing Chinese women from entering and patronizing their establishments out of fear of attracting potential reports of illicit sex activities and subsequent police raids. Extensive scholarly research studies have also discussed the unfavourable dimensions of migration and settlement experiences of PRC-born Chinese immigrant women across Asian societies, for example challenges faced by Chinese study mothers in Singapore; gendered racialization of new Chinese migrant women in Singapore; othering of Chinese migrant women in Malaysia; and more generally, discrimination against and impact on Chinese migrant women in Southeast Asia.

Part of this assemblage of myths on Dragon Lady is the Chinese mythology of fire dragon. The symbol of fire dragon carries a highly auspicious connotation. In Asian societies, especially ethnic Chinese communities, fire dragon bears significant symbolic meanings of majestic powers, supernatural might and heavenly greatness. There are twelve zodiac animal signs in 十二生肖 Chinese horoscope – 鼠 rat, 牛 ox, 虎 tiger, 兔 rabbit, 龙 dragon, 蛇 snake, 马 horse, 羊 goat, 猴 monkey, 鸡 rooster, 狗 dog and 猪 pig. There are five elements, 五行 in Chinese zodiac. The five elements 五行 are 金 Metal, 木 Wood,水 Water, 火 Fire and 土 Earth. In Chinese mythology, the dragon has been referred to as the god of clouds and rain and the king of seas. The symbol of dragon was reserved for Chinese emperors of multiple late Chinese dynasties, hence further elevating its sacred and royal image. I grew up watching Chinese period dramas that featured Chinese emperors wearing golden robes embroidered with dragons and anyone who used or wore the dragon symbol would be charged of treason and face execution by beheading. There is also a folklore that Chinese populations are 龙的传人, the descendants of dragon, which reveals a strong sense of cultural pride and superiority. Chinese parents, commonly 望子成龙, hope that their child will one day become a dragon, which does signify not only achievement of success but also attainment of true destiny.

Against this cultural backdrop, it is no surprise that baby booms could be observed in dragon years across Chinese societies in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and Malaysia. For example, in Singapore, it has been reported that fertility rates in dragon years are higher than in other years, especially the tiger years where Chinese couples avoid childbirth. According to official statistics, the total fertility rate for Singaporean-Chinese population dipped to 0.87 in the Year of Tiger in 2022, as compared to 1.18 in the Year of Dragon in 2012. The combination of Chinese zodiac sign of dragon and the element of fire is believed to ordain one with the most auspicious, prosperous, successful and formidable destiny. This combination is therefore arguably to be the most desired zodiac. Understandably, there was a baby boom in 1976, the Year of Fire Dragon across ethnic Chinese communities including Singapore, Malaysia and Taiwan. What that also means is that Fire Dragon 1976 babies in countries with significant ethnic Chinese populations arguably face heightened competition for access to resources and opportunities in education, employment and housing.

Born in 1976, I am one of these 火龙 fire dragon babies growing up with a larger birth cohort in an already intensely competitive Singaporean society. Not only do fire dragon babies in Chinese societies live under the expectations that fire dragon babies are destined to do great things and yield extraordinary success according to Chinese mythology, but many also live with relatively greater stress in competing for resources to survive and thrive having born in a larger birth cohort. Researchers have shown that larger birth cohorts suffer worse life prospects and outcomes due to increased competition. For example, in Singapore, ‘Singaporean Chinese born in the Year of the Dragon earn lower income than other Chinese birth cohorts’ and even other population groups not born in the Year of Dragon who enter the workforce as dragon cohorts consequently face greater competition and more stressful employment, wage and overall life prospects. One can imagine how these population groups’ life chances will be further challenged if they also face marginalization by intersectional dominant systems of race, heteronormativity, patriarchy and body ableism. Ironically, it turns out that Chinese parents, who have chosen to give birth to dragon babies in hope of giving their child a head start in life with an auspicious astronomical destiny, end up setting their dragon child up on a more treacherous path competing for limited opportunities and successes with a larger birth cohort.

The aim of evoking Chinese mythology of fire dragon or Dragon Lady is not to re-orientalize Asian women and reinforce Western imperial frames of racializing and othering Asian women. Rather, fire dragon feminism is about confronting head-on all of these myths, whether they are inspirational references of extraordinary aptitudes like 龙女 in Buddhism’s Lotus Sutra, 小龙女 in Chinese literary works, 火龙 fire dragon in Chinese astrology or demeaning constructs reflecting xenophobia, racism, Sinophobia and sexism. The framework seeks to understand how Asian migrant women’s lives are shaped under the influence and impact of this corpus of racialized, sexualized and ethno-cultural myths. Fire dragon feminism is interested in collecting the women’s stories of how they break free of these myths, queer power structures imposed on them and carve out their trailblazing path for collective survival and sustainability. Conducting an autopsy of the archive of myths, fire dragon feminism exposes the various hegemonic systems of patriarchy, sexism, misogyny, coloniality and racial capitalism constricting and restricting life chances of Asian migrant women, shaping their epistemes and ontologies and determining their life-sustaining strategies.