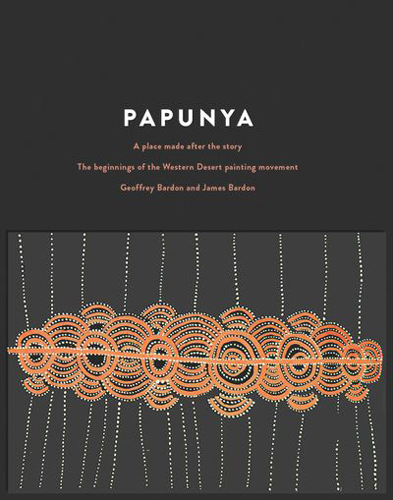

Papunya: A place made after the story by Geoffrey and James Bardon was first published by the Miegunyah Press in 2004 and reprinted several times in succeeding years before being issued as a paperback, under a different cover, in 2007; the paperback too, in 2010, was reprinted. The copy under review, however, is a brand new deluxe hardback edition, Bible-black, with a third cover, a beautiful honey-gold painting, Yam Travelling in the Sandhills, by Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri. Curiously, the painting has been rotated ninety degrees to make the cover image; inside it appears vertically disposed. In that version it looks like a map; in the other, a rhizome or even a bacterium.

The book, as books these days do, has another subtitle: The beginnings of the Western Desert painting movement; while the dual authorship refers to the completion of the text, with its remarkable illustrations and obsessive documentation, by Geoffrey Bardon’s younger brother James; with the help, one must assume, of an expert and unsung editorial team at Miegunyah Press after twelve cartons of Geoffrey’s files were delivered to their Melbourne premises following his death in 2003. Bardon was a Sydney art teacher who in 1971-2 became a catalyst amongst a group of Indigenous painters at Papunya; his subsequent connection with what became known as Papunya Tula Artists was lifelong and this book is its apotheosis; hence that not uncontentious second sub-title. But what about the first one? What does that mean?

A place made after the story is Bardon’s formulation; he uses it in the text with pride but without explanation. A place must be Papunya. If so, what is the story and why does it merit the definite article? Papunya was founded as a government settlement in 1957. A bore was drilled and those people, many of them so-called Old Pintupi who had taken refuge from the exigencies of life in the Western Desert at Haasts Bluff/Ikuntji, which was then running out of water, moved there. Lutherans from Hermannsburg/Ntaria came as well. Their presence was the reason Albert Namatjira was sent to Papunya in 1959 to serve out his term of imprisonment, for alcohol-related offenses, at the house of the resident missionary, Ernest Fietz.

In those days New Pintupi were still coming in from the Western Desert and they accommodated themselves alongside Luritja from the south and west, Warlpiri from the north, Anmatyerre Arrente from the north and east and perhaps some Anangu from the Pit Lands far to the south as well. It was a volatile mix in a volatile town – Bardon called it a Death Camp – in a period during which assimilation was being abandoned as the official policy of both Northern Territory and federal governments in favour of what would be called, imprecisely, self-determination.

Papunya Tula is a small hill to the north of the town; a site of honey ant dreaming. The name of the hill was selected, randomly off a map I suspect, by the authorities as the designation of their new town. A decade or so later, when a consensus was reached amongst the Indigenous peoples gathered there, Papunya Tula was also chosen as the name of the co-operative they founded and incorporated to manage the sale of their art. This became the model for most community-based art centres elsewhere: an independent, Indigenous-run enterprise which could liaise (usually through a white manager and in various complicated ways) with the larger world. There are now around a hundred of these centres active in Australia.

The reason for that choice of name by the artists seems to have been because, whatever their tribal or language affiliations, all groups exiled to Papunya shared, or could see a way of sharing, the honey ant dreaming. This may mean that the song lines of the honey ant extend into the lands of all of the peoples represented at Papunya, and across the desert into those of their more distant neighbours; or it may have been a compromise, tantamount to the adaptation of a familiar and widespread pattern to modern realities. Perhaps these statements mean the same thing. Perhaps we can say that Papunya Tula Artists P/L became a kind of secular dreaming.

Is this what Bardon meant? That Papunya, a place, was made after this, the story? I’m unsure. If it is, I don’t think it was all he meant. Because the other story which radiates so powerfully from these pages is that of Geoffrey Bardon himself: an heroic narrative in which a lone pilgrim, beset on all sides by the evil men and women do to each other – especially to him, and especially at Papunya – triumphs over the odds and single-handedly founds an art movement whose influence travels around the world.

Bardon is alone and persecuted among what he called his ‘violent and drunken’ white contemporaries; but is surrounded at all times by the loyal painters whose work he elicits, enables, documents, markets and sells. They are about thirty or so (numbers vary) and Bardon supplies them with boards to paint upon (pieces of plywood or particle board or similar), brushes and paint to paint with, and secure places in which to paint. He gives advice on what to paint, which includes: ‘nothing whitefella’ and ‘be smart, be cheeky’. On a mundane level, he ensures that brushes are kept clean, there is fresh water, the painting shed is tidy, the authorities unperturbed, and so forth.

An artist himself, he looks, consults, and makes suggestions. When a work is finished (he might be the one who decides), he documents it visually (two photographs of each painting) and draws an explanatory diagram that is usually annotated (the ‘story’ of the painting). He takes the works to offer for sale in Alice Springs, trucking them there himself, with the boards stacked up in the back of his Kombi van. The money is meant to go back to the painters in recompense for their labours; but money is a complex and difficult thing; and, in this version of the story, the rock upon which Bardon foundered.

There are many things that might be said about this myth/story and I will try to say some of them. One essential insight is that the art always means something different to those who made it from what it means to those who buy it; and is understood differently again by those who curate, exhibit, collect, and write about it. Perhaps this is the case with all art, but an added complication with the art of the Western Desert is that there is a secret/sacred dimension to the imagery which may not be disclosed to those without rights to it. So another function of the process of translation from the Indigenous to the ecumenical that Bardon oversaw was the requirement to negotiate what could and couldn’t be shown.

Of course he had to do this from a state of relative ignorance and mistakes were made. At the recent (2017) exhibition of Papunya boards in Darwin, now on show in Alice Springs, Tjungunutja: From Having Come Together, about a third of those notionally available for exhibition were, upon the advice of Indigenous stake-holders, sequestered from the show. Why? It is difficult to say. The question as to what, exactly, is given away when secret/sacred material is revealed is of some complexity; the risk may be as great for those to whom the forbidden information is imparted as it is for those who do the imparting.

It’s also the case that what is left unsaid has always in some sense been said; in the same way that what is said always partakes of what it does not say. Paul Carter, in an elegant, if hyperbolic, introduction to the book, honours this ambiguity in his conclusion:

Bardon could bear not knowing. He was not competitive with the truth. In encouraging the painters to conceal as well as reveal, to assert the difference of their knowledge as well as selectively communicating it, he deliberately refrained from colonising their dreams. Bardon respected their enigma as a site of latent social, political and psychic harmony.

While this description is both accurate and generous, it excludes from consideration what might be called the counter-myth which – along with the magnificent illustrations, the sometimes contentious or even erroneous documentation, the drawings, the taxonomic and index systems, the photographic portraits and the fragmentary, mostly anecdotal, biographies of the men who made the paintings – is the freight this book has to carry. That is, it has to support the weight of what Una Rey has called, not without irony, the myth of Bardon the Bard.

Geoffrey Bardon was born in Randwick in 1940 and came of age in the 1960s. He studied law at the University of Sydney but abandoned his legal studies without graduating and trained as a teacher instead, specialising in the teaching of art to primary and secondary school students. He taught in country New South Wales and Darwin before applying successfully for a position as primary school teacher at the government school in Papunya.

In 1971, Bardon drove from Alice Springs to Papunya in his Kombi van, over 250 kilometres of bad road, full of exalted ambitions for the task ahead. He wanted to make a difference. He also wanted to make films: to that end, he brought with him the technology necessary for producing high quality stills photography and moving pictures. He includes a summary of his gear in the text and it is the equipment of a serious professional film-maker. Like a latter day Jindyworobak, he also wanted to write and stage puppet shows, using Indigenous kids, characters, motifs, and story lines.

Bardon says he carried at all times on his person a passage from St Paul’s Epistle to the Corinthians, the famous verses at 1 : 13 which begin ‘Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels’, include the lines ‘when I was a child I spake as a child’ and conclude ‘and now abideth faith, hope and charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity’. Like his predecessor Rex Battarbee, facilitator of the Hermannsburg School of watercolour painting, he was motivated by his Christian faith; but, again like Battarbee, he was not one to proselytise. He wished to be known by his deeds not his words. Nevertheless the prose accounts he wrote about his time at Papunya are sonorous and reveal a messianic sense of mission along with an acute awareness of the persecutions to be suffered along the way towards martyrdom.

At Papunya Bardon saw his pupils, out of school, drawing patterns in the sand. He was looking for motifs for his puppet shows and was curious about the nature and meaning of those patterns, eventually deciding to bring them into the classroom, and into his teaching, as a form of inspiration for art making. The children responded with such enthusiasm that Bardon was soon relieved of general teaching duties and became exclusively an art teacher. He said his pupils called him Mr Patterns; but that name may in fact have simply been his mishearing of the Pintupi pronunciation of ‘Bardon’.

There were six outdoor murals painted at Papunya in 1971. The first ‘practice’ mural, which Bardon doesn’t mention, was in figurative realist style and showed a family group sitting down in the foreground of Haasts Bluff. It seems to have been painted by Bardon himself, perhaps with the help of the children, and was meant to demonstrate the new teacher’s talent (and perhaps his intent) to his headmaster, Fred Friis. Subsequent murals were mapped out with the help of Bardon’s teaching assistant and interpreter, Obed Raggett, a mission-educated Arrernte man from Hermannsburg. Bardon, like many white workers in remote communities, was not there long enough to learn to speak any Indigenous language.

Bardon said that after he and the children began mural painting he was visited by a group of older men who told him that the use of motifs in murals was not an appropriate thing for children to be doing because they did not know the full meaning of the marks they were making. And the consequence of that was the painting, by the men, of five more murals on the outside walls at the school, culminating in the very beautiful honey ant dreaming mural, illustrated in the book but now lost from the world. All of the murals at Papunya were painted over in 1974 – either an act of institutional malice or an unthinking piece of routine maintenance by the authorities.

Be that as it may, in Una Rey’s words, ‘the murals ignited a fever of painting onto small boards numbering around 1500 by thirty men between mid-1971 and August 1972 when Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd was formally established to manage the innovative painting economy.‘ Bardon is at his best when recalling this ‘fever of painting’, particularly when he evokes the atmosphere in the Great Painting Hall – one half of a Nissan hut – where the men gathered daily for communal painting sessions. He classified the works by their dreamings: Water; Travelling; Fire, Spirit, Myth and Medicine; Bush Tucker; Women’s Dreaming; Ritual Dance; My Country (Homeland); The Children’s Stories.

However, by the time of the actual founding of the co-operative, which he had helped inaugurate, Bardon had had a nervous breakdown and left Papunya. The breakdown seems to have involved a loss of faith, not so much by Bardon in the painters as by the painters in him. At a meeting in mid-1972, the painters sat on the ground and chanted ‘money, money, money’. Bardon gives an account of a later meeting, during which an unnamed administrator stood before the men with a cheque of over $800.00 in payment for art works sold in Alice Springs and then proceeded to make various deductions from it until all that was left to be distributed amongst the artists was the meagre sum of $25.00. Here he is mistaken; or disingenuous. In fact, as Luke Scholes has pointed out, payment was $25.00 per artist and the deductions were to pay for the materials, purchased on credit, that the paintings had been made from.

Art had always been seen by the painters of Papunya Tula as a means of making money; as it had been for their predecessor Albert Namatjira and the other painters of the Hermannsburg School. Art was also seen as a money-making enterprise by missionaries looking to find an economic basis for communities whose lifestyle was threatened by European expansion. So, for these painters to find out that they were not going to be paid properly for what was indubitably theirs to sell seems a justifiable occasion for an expression of anger at the duplicity shown by white authorities. It was not Bardon’s duplicity; but he was an unwitting agent of it; and he seems to have taken that to heart.

He went from Papunya to Alice Springs and thence to Sydney, where he was admitted to the notorious Chelmsford Private Hospital in Pennant Hills for Deep Sleep Therapy. Patients at Chelmsford were pumped full of barbiturates and tranquillisers and left in a state of unconsciousness for as long as 39 days, during which time they were fed intravenously. They were also, while unconscious, administered electro-convulsive therapy (ECT). Under the ministrations of Dr Harry Bailey and his ‘beautiful chemicals’, 26 people died at Chelmsford, sometimes choking on their own vomit while undergoing shock treatment. Many more committed suicide.

A case can be made that Geoffrey Bardon never really recovered from his nervous breakdown and subsequent ‘holiday’ at Chelmsford; but we will have to wait for Kitty Hauser’s forthcoming biography to find out more. A damaged man, he returned to Papunya quite a few times over the years and continued to work with some of the painters; but his version of the events of 1971-72 seems frozen at a site of miracle and trauma, neither of which is, nor can be, properly comprehended. This accounts for his ahistorical writing, which suggests that Dreamtime was followed by Bardon-time; and after Bardon-time, a vague decline into aestheticism.

Bardon is better understood as an artist than as an art historian, theoretician, or intellectual. His primary analytical tool, a distinction between archetypes and hieroglyphs, is hard to grasp and, once grasped, of limited usefulness. You might as well speak, as Bardon himself sometimes did, of dreamings instead of archetypes; and of motifs rather than hieroglyphics. On the other hand, as a painter himself, he understood an essential fact about these works, which were usually made lying flat on the ground: in them there is no up and no down, no right and no left. They can be, and by the artists were, viewed from any point of the compass. But you can still hang them on a wall.

Bardon’s function, then, might be understood as the overseeing of a process by which a kind of painting that was ephemeral and took as its support either human skin or the ground of the earth, was transferred into a form that was portable and durable and, for those reasons, saleable. His basic insight was visual: he saw the splendour of the works and enabled their transference from three or four or more dimensions into two; and is thereby entitled to claim to have played a major role in the beginnings of the Western Desert painting movement, which he also named. But he was by no means the only one.

Rex Battarbee was still alive, still working, and still living in Alice Springs when Bardon made his first trip into town with his Kombi full of painted boards for sale. It’s said he went around to Battarbee’s modernist, solar-panelled house in Sturt Terrace alongside the Todd River and knocked on the door; but Rex wasn’t home that day. Bardon went instead to see Patricia Hogan, who with her husband ran a caravan park in Alice, and she became the dealer who sold on most of the boards painted in Papunya.

Pat Hogan was a pioneer as credible as Battarbee had been; like him, she supplied artists with materials, fine-tipped brushes for instance, with which to give their work a better finish and thus increased saleability. It was through Hogan’s efforts that the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) acquired over 200 of the boards in the 1970s, when no other Australian institution, with the reluctant exception of the Art Gallery of South Australia, nor most private collectors, wanted a bar of them.

Bardon leaves Battarbee out of his account and hardly mentions Namatjira either. This seems to have been because of a desire to exclude anything whitefella from ‘the new painting’. Modernist critics adjudged the Hermannsburg School flawed because of its adoption of a European style which was unable to encode the ‘authentic’ preoccupations of the painters. A moot point: Wenten Rubuntja, an Arrernte man who painted in both styles, said that one (‘dot painting’) was about law and the other (watercolours) about country. Keith Namatjira and other watercolour painters exhibited with the Papunya artists at David Jones in Sydney and at other places and in the early days outsold them: law and country, side by side.

The suppression of the Battarbee/Namatjira story, and its presumed motivation in a purist attempt to deny the validity of the tradition they represented, is not the only omission. Research by Vivien Johnson proves beyond doubt that some of the Papunya boards were painted before Bardon arrived on the scene. It’s also likely that the artists at Papunya were influenced by the mural painters at Yuendumu to the north. More recently, it has been proposed that the origin of the Papunya Tula movement itself predates Bardon’s arrival. The catalogue for the 2017 exhibition Tjunguṉutja quotes Bobby West Tjupurrula:

Pintupi people were having a hard time in Papunya. There was a lot of fighting, a lot of arguments and they wanted that to change. All the tjilpis [old men], it was their idea. The Pintupi men wanted to show people in Papunya that they had really strong law, Tingarri. They wanted to share it, teach it, because they were all together in Papunya and they wanted to show this other way, Pintupi way, Tingarri. They were giving it as a gift, that Tingarri. Warlpiri, Luritja, Anmatyerr, were watching, waiting for their turn. After that, after Tingarri, that’s when they did dot painting, body painting. Then they did that [Honey Ant] mural at the school, made it public, letting everyone know they were all together.

Bardon’s arrival must have seemed like a dream come true: an idealist, a trained teacher, a painter too, with that beautiful camera gear and the skills with which to use it. He was a man who owned or commanded all the attributes necessary to support an art movement. The discovery of a cupboard full of unused materials at the school, including a large quantity of poster paints, must have seemed prophetic as well. But, as everyone knows, any seed, prophetic or otherwise, must fall upon fertile ground; and at Papunya, that ground had been prepared by the Tingarri accord of 1970.

The central figure became Kaapa Mbitjana Tjampitjinpa, of Warlpiri and Anmatyerre Arrernte descent, founding member and first chairman of Papunya Tula Artists P/L and acknowledged leader of the painting movement, with a distinctive style all of his own. Bardon’s attitude to him is equivocal; he criticised Kaapa’s prize-winning work Gulgardi (see below) for being too ‘influenced by European conventions and materials’. And while he recorded Kaapa’s role as a leader – of the work in the Great Painting Shed – he was also ambivalent about his character:

Kaapa was not as tall as many of the Anmatjira Aranda but he was very quick to see what others might not see at all. (I often thought he saw far too much, and perhaps this was why he drank more than he should.) He always moved in a fast, deft spring-walk, intense and convoluted as he whispered in his strange, pressed-together, mixed-up English. Kaapa was very bright, but very down to earth as well, an extraordinary survivor in a despairing environment. I remember him particularly for his intense way of seeming to be everywhere at all times, doing things mysteriously and well.

For some years prior to 1970 Kaapa and some of the other men had been using traditional designs to make art works for sale, including wooden carvings and watercolour paintings. In mid-1971, a welfare officer named Jack Cooke took six of Kaapa’s paintings, evidently pre-Bardon works, into Alice Springs and entered them in the Caltex Northern Territory Art Award. Gulgardi, aka Men’s Ceremony for the Kangaroo, shared first prize with a painting by Darwin artist and art teacher Jan Wesley-Smith. Although Indigenous artists had entered works in the Caltex previously, no one before Kaapa had won this or any other contemporary art award; it was the first public recognition of a Papunya painting. Historian Dick Kimber recalls:

The first painting I saw was one of Kaapa’s (Tjampitjinpa) and the instant impact on me was amazing. I immediately wrote to Bob Edwards (then curator of anthropology at the South Australian Museum, who became the first director of the Aboriginal Arts Board of the Australia Council). If credit is due to anyone for keeping Papunya painting going at that stage it ought to go to Bob Edwards. Bob had had a love of Aboriginal art especially rock paintings for years and he came out here and looked at the art and the community and organised funding for the administrator.

These were, from late 1972, the Whitlam years. The following year, 1973, the Labor government restructured the Australia Council for the Arts, adding the Aboriginal Arts Board, which gave consistent financial and other support to what was unfolding at Papunya. Dick Kimber also credits Peter Fannin, a fellow school teacher, colleague, and flatmate of Geoffrey Bardon’s, who took over from him when he left so precipitately in mid-1972. It was Fannin – a botanist by profession – who oversaw the transition from painting on boards to painting on canvas, a move which Bardon, for reasons that are obscure, deplored.

More recently Luke Scholes, by going back to the archives, has shown that other critical figures have been left out or anonymously denigrated in Bardon’s version; Warren Smith, for instance, sometime Superintendent at Papunya; Mary White, an advisor on Aboriginal projects to the Craft Council of Australia; Laurie Owens, another Superintendent. These three, along with Jack Cooke and others like Pat Hogan, worked long and hard to foster the movement Bardon would claim as his own.

And then there were the Artist Co-ordinators who succeeded him. Peter Fannin (1972-75) was followed by Janet Wilson and Dick Kimber (1975-77), John Kean (1977-79) and Andrew Crocker (1980-81). Kimber again:

Crocker, an English barrister and quite a flamboyant character, arrived as art coordinator. He got on the phone and rang every wealthy person he could think of saying ‘I think you ought to have a collection of this work.’ He was the one who got Robert Holmes à Court interested. Holmes à Court was one of the most high profile people in Australia and suddenly his collection from Papunya was photographed in Vogue and major newspapers. Suddenly art from Papunya was a highly desirable thing to be collecting.

The aestheticism which Bardon disparaged, characterising it as a decline from the purity of the early years, might just as well be seen as intelligent adaptation by the painters to a market which was, from the 1980s onwards, increasingly international in scope. They saw that this market valued certain aspects of their paintings above others and, as any artist might, adapted their work to satisfy that market.

This is not a sign of inauthenticity; after all, the painting was always meant for sale and this was also why secret/sacred elements had to be suppressed, omitted or disguised within it. You could argue that the withheld elements, which are always somehow present as well, give value to these paintings; and that both buyer and seller knew this. There are many ways of dealing with the secret/sacred, just as there are many ways of dealing with money. Ultimately, though, you have to think the two are incompatible.

So Bardon’s legacy, despite the errors he made and the resentments he nurtured, is complex, layered, various and even visionary. On a visit back to Papunya in the later 1970s, he commissioned a painting from Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri. This huge and majestic work, Napperby Death Spirit Dreaming (1980), which Tim Leura completed with the assistance of his skin brother Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, is a world masterpiece in which Bardon did come to recognise a future for the style he helped facilitate, writing:

it is revolutionary in the context of Western Desert art because through it Tim appears to be stepping outside his immediate tribal affiliations to comment on the various aspects of spirituality in his own life, with deeply felt representations of his soul’s journey.

This too is part of Bardon’s legacy; and his own soul’s journey – with all of its complexities, its twists and turns, its joys and despairs – is the hidden subject of this vast, perplexing, beautiful, and compelling book.

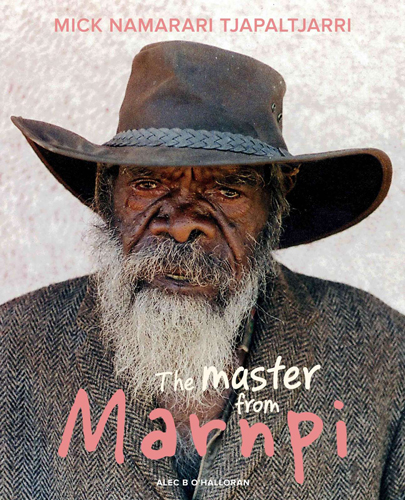

It is something of a relief to move from the Sturm und Drang of Bardon’s Papunya to the straight-forward charm of Alec O’Halloran’s biography of Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, The master from Marnpi. The difficulty with any biography is the assembling of the materials necessary to construct, or re-construct, the shape of a life. In the case of a Pintupi man born at an undisclosed location in an unknown year, you might think such materials altogether lacking, at least for the early life; but O’Halloran shows that is not the case. He establishes, for instance, that Marnpi was Namarari’s place of birth; and that the year was probably 1923.

Then he uncovers, fortuitously, anthropologist Norman Tindale’s entry of two photographs and some physical and family details of a nine-year-old boy he called Ngamarare in a register drawn up by the Board of Anthropological Research at Mt Liebig in 1932; and proceeds from there, using mostly oral history sources, until the welter of other forms of documentation starts to come in from Papunya in the early 1970s.

Namarari was a wati, an initiated man who lived, from the age of nine onwards, in complex interaction with the relentless, frequently destructive, advance of white culture. As a stockman, labourer, councillor, and painter, he worked with a variety of Europeans, including station owners, pastors, missionaries, art advisors, teachers, tradespeople and administrators. Amongst his own people his connections were extensive and always approached in a spirit of co-operative innovation. He was also an educator – of both white and blackfellas.

His memories of his early days are predominantly culinary and geographical; he recalled, in detail, places he went and the food that was hunted and gathered and eaten there. As you read these accounts of times and places and long ago meals, you begin to see before your mind’s eye examples of the paintings Namarari and others made, detailing this dreaming or that, this food supply or that – yams perhaps, or honey ants, where and how emu or kangaroo or bandicoot or dingo might be taken.

Other recall is less happy. When Namarari was a boy, his father did not return from hunting one day and, after the family followed his tracks, they found him dead amongst the dunes, with the spears that killed him still sticking out of his body. He was the victim of a revenge killing and the shock to his mother, Namarari’s grandmother, was so great she threw herself into the fire and burned to death. This too the boy witnessed. Much later, as an old man, Namarari made three pencil drawings of these events.

O’Halloran re-tells the life chronologically, with essay-like digressions when he feels more background information is necessary for a fuller comprehension of the story. He has a light touch, both in the essays and in the re-telling, and leaves things open-ended. Where detail is lacking, he contents himself asking questions he does not feel obliged to answer. He doesn’t speculate over much either: there’s very little he must have felt, he must have thought. The effect of this is to represent Namarari with dignity intact and his enigmatic nature as a subject of biography fully attested. This is a considerable achievement, especially in a book which is the author’s first.

Namarari was a quiet and gentle man, dedicated to his family, fond of hunting and, in later life, of painting. Indeed the two activities had an intrinsic connection in his mind. Many people remarked upon his ability to wait: for an animal to be taken as much as for a cheque to arrive; for a painting to be finished or a garden to come to fruition. Occasionally he did ‘blow his top’ – for instance, on the day when a promised ride did not eventuate he took to the door of the Toyota with an axe, delivering six clean blows, and six gaping wounds, into the metal.

Most of those who knew him well – like Daphne Williams, manager of Papunya Tula Artists, who worked with Namarari over two decades – also describe a man with a subtle, understated sense of humour. When asked about Albert Namatjira, he said: ‘He used to do hills. Like from here he would paint that hill over there. That was his work . . . he just painted hills. His family did that. Yes his sons. I used to give him food. He got tired. The whitefellas thought he was a very good artist.’ His take on Bardon is equally wry. At first he appears not to remember his name: ‘At Papunya. We would paint him box. Who was it who gave them to us? . . . Yes, Geoff Bardon. Whitefella . . . He used to give us pieces of wood. Wooden sheet that had fallen down from the ceilings of old buildings.’

An interview with John Kean confirms that money did indeed become an issue at Papunya. Kean returns to the subject of the time Bardon spent at Papunya, to which Namarari replies: ‘For a while, might be one year . . . one year. We said no, because he didn’t give us money . . . he did not give us any money, little bit money.‘ In this exchange it becomes clear that, whatever heroic narratives whitefellas might construct around what happened at Papunya, for artists like Namarari, Bardon was an episode (and not an especially important one) in a life in which the pleasures and demands of painting became a main concern.

Namarari was the quiet achiever among the Papunya painters. After a gathering or a meeting, those who presided over it were sometimes unsure if he had been there at all. In an environment that was often competitive – for materials, for sales, for rides – he did not compete. And yet, because of his consistency, his dedication, and the sheer splendour of his paintings, he ended up with all of the accolades: three major prizes, four solo exhibitions.

Like Namatjira before him, he travelled to the eastern cities to receive the prizes and awards, to appear at openings, to meet inner city poets, and gallery and museum people, to be feted by prime ministers and other dignitaries. When asked what Paul Keating said to him after he had been presented with the inaugural Red Ochre Award in Canberra in 1994, Namarari replied, with his characteristic dry wit: ‘Wangka wiya: talk no.’ Keating didn’t say anything.

By this time, like a lot of Pintupi during the out stations movement, Namarari had moved back onto his traditional lands and was living at Kintore near the Western Australian border; or at his own place at Nyunmanu, away to the south and east near Marnpi in what was his birth country. When he died of kidney failure in the Hetti Perkins Home for the Aged in Alice Springs in 1998 he had the name of his country on his lips in an unappeased desire to return there to die. He is buried at Kintore.

The eleven chapters of the biography are illustrated with reproductions of paintings and with documentary photographs as well as landscape shots; the second part of the book, ‘Painting Stories’, presents Namarari’s work thematically in seventeen roughly chronological sections. From the early, semi-figurative work of 1971-2, Namarari develops into an abstract painter of great authority and power, with a grand conception of space and time in which to elaborate his dreamings. The master from Marnpi is worth owning for the images alone. Its compilation was clearly a labour of love, out of which Alec O’Halloran has made a beautiful book about a wonderful man.

Papunya: a place made after the story has a ghost companion. In the same year Bardon went out west, 1971, Angus and Robertson in Sydney published T.G.H Strehlow’s Songs of Central Australia in a limited edition of some hundreds of copies. The book was withdrawn from sale soon afterwards because it included secret/sacred material and has never been re-printed; it is inaccessible now unless you want to pay a large amount of money for a second-hand copy or are prepared to spend days reading it under supervision in a library. If the language of the Bible was the inspiration for Bardon’s account of his time at Papunya, Strehlow preferred Greek and Norse myth as models for his translations of Arrernte songs into English poetry. Both enterprises partake of the heroic as figured in European tradition.

And both are haunted by the spectre of secret/sacred knowledge appearing in works to which, notionally, everyone has access. Given the ubiquity of this problem in anything to do with cross-cultural matters in Australia, it’s surprising how little has been written about the fate of those who transgress. For most white Australians the notion that giving away information might lead to your death, or to the death of someone else, seems outlandish. It evokes a Mafioso-like criminal underground; or espionage; or the dangers of war; or witchcraft. Even in an age of identity theft, data dumps, and constant surveillance, we still don’t believe that giving away personal information could cause death. For some Indigenous people, the opposite seems to be true.

This might be because, in pre-colonial times, people depended utterly upon the resources of a local area and were thus vulnerable to any loss of knowledge which could undermine their access to, or custodianship of, country. Furthermore, for any tribal group, like the Pintupi, living on their own land, knowledge of country was held, not by some over-arching authority, but by the wati – the old men – who learned it through the complex and life-long processes of initiation. This knowledge was not abstract; it was practical and included a component that has been called, variously, care-taking and/or guardianship. And law. What one knew was not what anyone else might know: knowledge, while part of a tapestry of similar knowings, was unique.

Knowledge could however be shared; especially, it seems, during ceremony. It follows then that full comprehension of country would only emerge on occasions when everyone partook of its revelation. And, in turn, if someone gives away part of this knowledge, everyone loses a part of the whole; which means that it is no longer whole. For people who live in a symbiotic relation with country, the loss of knowledge might indeed mean death. Yet the fabric of interwoven knowings is not a static thing, it is dynamic, always fraying and always being repaired again. The painting movement might then be seen as another strategy for effecting this ongoing repair.

I don’t know if Bardon or Strehlow thought of the secret/sacred in these terms. Strehlow must have had some comprehension of it; but his response to the loss of knowledge he saw going on exponentially all around him was a despairing attempt to retrieve all that he could lay his hands upon. His belief that he had actual rights to the dreamings he was given custodianship of, and the artefacts retrieved in his name, is questionable if not repellent.

Bardon, presumably, wanted the painters to exclude too much secret/sacred knowledge from their paintings and worked to make that happen. After all, the saleability of the works was in question. On the other hand, it was the power of that knowledge which gave the work its aesthetic charge and thus made it desirable for buyers: no whitefella stuff made it far more likely that whitefellas would buy a painting. Nevertheless, there is a sort of egotism abroad in Bardon’s texts too. I lost count of the number of times he recorded that a work was done for me, given to me, initiated by me; that me, however, is never interrogated.

Alec O’Halloran does not make that mistake. He is scrupulous in the narration of his incursions into a culture which, he would probably agree, he does not fully comprehend. Thus the agency of Mick Nararari is preserved, even when considered as an historical figure. Whereas the Bardon book, for all the beauty and power of its images, its copious documentation, the intrinsic interest of its biographies, and the wonderful photographic portraits (many taken by Allen Scott in 1972), remains weirdly time-lapsed.

It might be seen as another example of the Australian propensity to mythologise past events and thereby freeze them in time. As in the story of Gallipoli, say, or of the explorers Burke and Wills, or even that of the recently deceased poetic giant Les Murray – given a choice between trying to make sense of the complex unfolding of a real event and representing its mythic counterpart, we always seem to want to do the latter. We print the legend.

Meanwhile the view from the other side remains largely unexamined. I wonder, for instance, how many people, even amongst those interested in such things, have read At Home in the World by Michael Jackson? This report of his fieldwork amongst Warlpiri in the early 1990s is rigorous in methodology, empathetic in approach, and never attempts interpretations that would not be sanctioned by those whose world view he is trying to interpret. As such, it embodies real insight. Jackson went back to sit down with the Warlpiri to revise the text in consultation with his informants before publishing.

More will have read Kim Mahood’s essay ‘Kartiya are like Toyotas: white workers on Australia’s cultural frontier’, whose title borrows from a Western Desert woman’s remark that ‘when kartiya break down, we get another one’. Una Rey suggests, persuasively, that any further study of Bardon should take place under the auspices of the genre of martyrology. If so, Mahood’s essay, which is by turns hilarious, sobering, gut-busting and wise, would be an excellent place to start; with Bardon as the exemplar of a type commonly found today among white workers at the hundred odd art centres in Australia.

So there are other perspectives. And they can be startling, salutary, even healing. One thing that amused Mick Namarari in later years was the memory of the time he was given his first cheque, in payment for stock work he did at Tempe Downs station in the 1930s and, not knowing what else to do with it, threw it on the fire.

The whitefella beckoned to me and said, “This is a lot of money, eh? Big money. Just your money, working.” Working money. I looked at it, and thought, “What is he giving me? Money? No it’s only money.” [laughs, looks at Batty]. I burnt it in the fire. (Swear!) It was a lot of money.

The money question is as unresolved as the secret/sacred nexus. Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri said ‘the money belongs the ancestors’, emphasising that the art movement was a strategy enabling the culture to adapt to present realities while continuing in its essentials unchanged. But once a work is sold, it doesn’t belong to the artist anymore; in the same way that, once a secret is told, it’s no longer a secret. In both cases, however, some mysterious residue remains in the possession of the artist and/or the teller. So that all of the Papunya boards, along with subsequent art from the Western Desert and elsewhere, continue to derive meaning from the sacred/secret knowledge concealed within or excluded from them. This is precisely why they are sold along with a story – even if the story itself is abbreviated, unclear or even made up.

The intent might have been to sell a de-sacralised version of a dreaming, with its esoteric charge somehow intact, while at the same time withholding the true version for those for whom its disclosure is a matter of life and death. Leaving aside the question of whether this strategy works, it’s worth noting that the distortions involved in the exchange of paintings for money aren’t confined to Indigenous arts practice. It’s something everyone in the art world is familiar with and, if it hasn’t yet been resolved in Alice Springs, it hasn’t been in New York or Paris or London either.

It’s also strange how Geoffrey Bardon’s story has itself become a kind of dreaming – inhabiting an uneasy middle ground, along with the nascent dreamings of Murray, Gallipoli, Burke and Wills and the like; while retaining the potential to take its place beside more ancient dreamings. This is a puzzle that only time can solve. Meanwhile, if we are as patient as Mick Namarari was, we may contemplate the artworks between the pages of these two fine publications which, like all good art books, are practically inexhaustible. That we might not know exactly what we are looking at becomes, in the end, an enticement towards further wonder. And wondering.

Works Cited

Susan McCulloch and Emily McCulloch Childs, McCulloch’s Contemporary Aboriginal Art: the complete guide (Victoria: McCulloch & McCulloch, 2008).

Michael Jackson, At home in the world (Sydney: HarperPerennial with Duke University Press, 1995).

Vivien Johnson, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists (Alice Springs: IAD Press, 2008).

Kim Mahood, ‘Kartiya are like Toyotas: white workers on Australia’s cultural frontier’, Griffith Review 36 (April 2012).

Una Rey, ‘Bardon’s legacy: paintings, stories and Indigenous Australian art’, in Mediating Modernism: Indigenous Artists, Modernist Mediators, Global Networks, edited by Ruth B. Phillips and Norman Vorano (Durham: Duke University Press, forthcoming).

Wenten Rubuntja with Jenny Green; with contributions from Tim Rowse, The town grew up dancing: the life and art of Wenten Rubuntja (Alice Springs: Jukurrpa Books, 2002).

Judith Ryan, ‘The Quick and the Dead, Purchasing Indigenous art 1988-1990’, The Art Journal of the National Gallery of Victoria 44 (May 2014).

Judith Ryan and Philip Batty, Tjukurrtjanu: origins of Western Desert art (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2011).

Luke Scholes (ed.) et al, Tjungunutja: From Having Come Together (Darwin: Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, 2017).

— ‘Unmasking the myth: the emergence of Papunya painting’, in Tjungunutja: From Having Come Together, (Darwin: Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, 2017)..

I’m grateful to Greg Lockhart, Alec O’Halloran and Una Rey, who read and commented upon earlier drafts of this review. The Master from Marnpi is available online here.