Long before the Stella Prize, there was Stella herself, but also Ada, various Marys, Catherines and Elizabeths, Tasma, Rosa and so on. The herstory of women writing in Australia is long and distinguished, a feminist literary tradition. Debra Adelaide’s 1988 critical anthology A Bright and Fiery Troop showcased the variety and innovation of Australia’s pioneering women writers, which included the first novel written and published in mainland Australia (The Guardian by Anna Maria Bunn, 1838). Other achievements: Ellen Davitt wrote the first murder mystery novel in Australia with Force and Fraud (1866) and Mary Fortune wrote the longest early detective serial worldwide, forty years of the ‘Detective’s Album’ from 1868-1908. It might be fitting for a retrospective Stella Prize to be instituted, to honour such women.

In the context of their time, they were second-class citizens (as an elderly female relative of mine used to describe herself). They had to fight for respect and even if they were successful, they tended to be quickly forgotten. It took second-wave feminism for Barbara Baynton’s powerful fictions of the bush to receive similar appreciation to those written by her contemporary, Henry Lawson. Louisa, mother of Henry, also had to wait for posthumous dues. Many others have been rediscovered, a process that is ongoing and richly rewarding. More will undoubtedly be found.

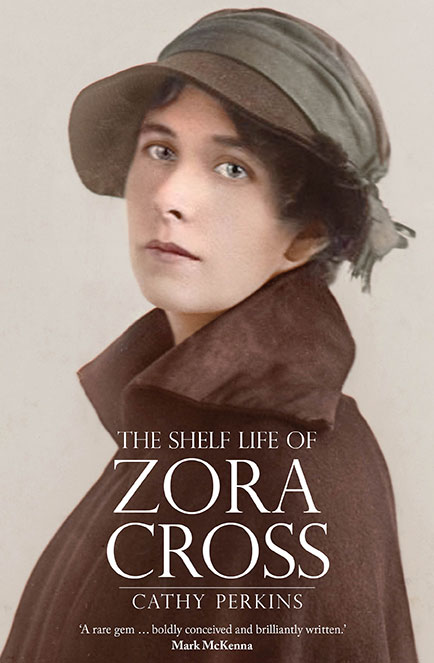

These two biographies are both devoted to the ‘scribesses’ of Australia, one by an experienced and much-awarded writer, the other by a newcomer. Niall’s is a group portrait, of Ethel Turner, Barbara Baynton, Henry Handel Richardson and Nettie Palmer. The first three are well-known, the last less so. Perkins’ book is devoted to a subject obscured by time and literary neglect: the poet Zora Cross. Even the dwindling band of Australian literature scholars are not guaranteed to recognise her name. The two books are complementary and yet different, overlapping in details, but when put together form a compendium of creative women’s lives in the first half of the twentieth century. They also reveal complex influences, networks of friendship and relationship.

Friends & Rivals comprises four interlinked essays presented as two diptychs: Baynton and Turner; Richardson and Palmer. Group studies of Australian women writers are rare, and perhaps the book closest to Niall’s is Sylvia Martin’s 2001 Passionate Friends, about Miles Franklin, Mary Fullerton and Mabel Singleton. Yet as the title announces, Niall’s subjects are not always friends, indeed some did not even meet. Tea between Baynton and Richardson, both formidable personalities, could have been fiery, or exquisitely awkward. Sadly it remains only an intriguing possibility.

Friends & Rivals begins with a personal return: Niall’s first book, Seven Little Billabongs, about Turner and Mary Grant Bruce, was published in 1979. In the intervening decades, Niall has ranged widely within the matter of Australian culture, from Martin Boyd (who fictionalised Baynton), artists like Judy Cassab, and the multi-award-winning Mannix. Unfinished business may be inferred, the niggle of a subject who will not let go of a biographer’s imagination.

Such revisiting can involve new perspectives or information. The latter is a genuine bugbear for the biographer, who can rarely be certain that she has all the facts. I found definitive proof that writer Fergus Hume was gay months after my biography of him, Blockbuster, was published. Niall herself told me that she leaves a finished manuscript for a year, just in case. Embargos on private papers can expire, or long-lost letters re-appear in attic trunks. Most recently digitisation has revolutionised research, as with the online databases of the English censuses. Sadly for Australia, federal budget cuts in 2016 forced the National Library of Australia to cease adding to the online database Trove, which makes newspapers and magazines available for electronic searching. Private funding has filled something of the gap, but the situation is a genuine disgrace. In contrast New Zealand’s Papers Past is ongoing, splitting digitisation costs with community groups.

In Niall’s case more information has emerged about Turner in the forty years since Seven Little Billabongs. Offcuts and oddments of information thus take on new significance, as with the anecdote which opens Friends & Rivals: Baynton taking her friend Turner diamond shopping. Impecunious authors may weep, the more since both women were independently wealthy. Turner was then several decades into a career as a successful childrens’ author, which would continue productively for several decades more. Baynton in contrast had a short and explosive burst of writing, then settled for the more lucrative pursuits of investments and collecting. She was an expert on precious stones, wearing them like trophies, portable status, though the display signalled what she was: a parvenu.

Both women were good at business, conservative, pro-conscription and anti-female suffrage. They were also not what they seemed. The long migration voyages between England and Australia enabled personal change, inconvenient pasts discarded. Baynton would claim she was the product of an enduring if illicit shipboard romance. Indeed she was, even if she elevated her parents’ caste, a carpenter fabulated into a Bengal Lancer. Similarly, Turner emigrated with her mother Sarah Jane, who already had children by two different men, and would marry again in Australia. Neither story was unusual in the annals of emigration: Sarah Jane’s story has its parallel in my family too.

The Turner family history held that her biological father died in Paris –although already one biographer had been unable to find any record. The truth behind the mystery is available for all to see in the UK census records, which reveal the young Turner, but no evidence her parents married. Both writers were thus illegitimate, with shared if unspoken anxieties about their origins. They remade themselves into worldly successes, Turner serenely, Baynton never without turbulence.

That they could be friends, a tribute to Turner’s sweet temper rather than Baynton’s very sharp tongue, was due to the fact that they were not rivals. Certainly, they likely coincided in the corridors of the Bulletin, but their audiences were completely different. Turner may have hoped to become a novelist of adult life, but her publishers disagreed. Baynton’s work was utterly unsuitable for children.

In having a subtitle of ‘four great Australian writers’, Niall challenges received notions of what makes Australian literature great. She recalls with some acerbity being asked to provide the ‘kiddylit’ chapter for a reference book. Children’s writing supports the publishing industry almost as much as romance, but is only marginally less despised by those academics and critics seeking to create a national canon of ‘serious’ authors. Yet many would judge that Turner drew the Australian childhood with lasting significance. To support her argument Niall recalls that a live reading among academics of Judy’s death from Seven Little Australians made Randolph Stow cry.

Friends & Rivals also shows the blessings of a good, supportive husband for women writers. All four had difficult childhoods, Palmer’s with extreme piety and dead siblings: ‘a household peopled with small plaintive ghosts’ writes Niall, a phrase both elegant and absolutely apt. John Curlewis never minded Ethel occasionally making more money than he did, and also engaged with her work. Dr Baynton groomed his young bush wife into a sophisticated matron and let her travel to England alone in search of publication. The most extreme example was John Robertson, famously sharpening his wife’s pencils for her hours of solitary work. If there is something of George Lewes here, a model even, then both men were astute talent-spotters: Mary Ann Evans became George Eliot and Ethel Robertson became Henry Handel Richardson.

Nettie Palmer had Vance supporting her, but not monetarily. Had she ever been more successful than him in creative writing he might have regarded her as a rival. As a freelance journalist she earned both the bacon and a reputation in her own right. Her devotion to his non-existent genius, including selfless promotion, has not been justified by subsequent critical assessment of his work. Even at the time Richardson found it tiresome to receive Vance’s books in the mail. She preferred that Nettie promote her for a Nobel – and she happened to be right. Yet Richardson also frustrated Nettie’s notion of being her biographer, via an embargo on her literary papers. Likely she thought Nettie unworthy, although Niall notes that in her correspondence Richardson was catty about the couple. Had Nettie been able to read them, she could have been deeply hurt.

The cumulative effect of this book is a concise, effective appraisal of lives and achievements: the decent, hardworking Turner, the conflicted, difficult Baynton, with Richardson reading as intense and withdrawn. Palmer she reappraises as a great critic, a major figure in promoting Australian literature, without colonial cringe. And yet the last sentence in the book, the last word or verdict, terms them outliers. As Niall uses words precisely, what is meant here is that there was nobody like them – but also that they were not of the mainstream.

Friends & Rivals is sensibly kept under 300 pages, but there are gaps. One instance: I would have liked to know what Niall made of a riposte, when Arthur Upfield did to the Palmers what Boyd did to Baynton in his Brangane. Nettie gave The Sands of Windee (1931) an adverse review, about which Upfield was so upset he fictionalised Vance unmercifully in the 1948 An Author Bites the Dust. (Spoiler alert: the pretentious author and critic Mervyn is murdered and the killer is his wife.)

Cathy Perkins is a debut biographer. She has not Niall’s breadth of experience, yet her work is confident and she breaks new ground with this biography of Zora Cross. Many of the figures featured are familiar, for Cross intersected with many gifted Australians, from Norman Lindsay to Mary Gilmore. As Perkins ably proves, she deserves a book to herself.

The subject has novelty, but so does the treatment. In writing a biography the typical progression is chronological. Perkins varies it by writing Cross’s life as a series of relationships – something very important for women. All can be related to her writing, as editors, friends, subject matter, or her publisher George Robertson of Angus and Robertson. Even unexpected juxtapositions can work, the Lindsay chapter enabling the contrast between his sexual expression – both in person and art – and that of Cross.

There is one notable point of intersection between the two books: Cross had Turner as a mentor, in her role as children’s page editor of the Illustrated Sydney News. (Small wonder the Australian Book Review selected Niall to review Perkins’ book on Cross in its December 2019 issue.) Certainly Cross was as hardworking as Turner, Palmer and Richardson, though considerably wilder. They were proper, with unexceptionable private lives. Cross, while only five years younger than Palmer, had more freedom, including to err, as the conventional morality termed it. Not all women writers of the Victorian era were virtuous – consider Fortune, Ellen Clacy and George Eliot herself – but it took secrecy or money to maintain their careers.

Attitudes had relaxed in the twentieth century, with heroines not automatically killed off fictionally for loss of virtue. Still eyebrows were raised at the open sensuality of Cross’s 1917 Songs of Love and Life. One of the joys of Perkins’ account is that Norman Lindsay did not want to do the cover art, due to his bias against women’s lovewriting: ‘from the ice-chest’, he said. Happily it was not shared by the readership, for the book was a bestseller.

Cross was a married woman, even if her husband had vanished, and she knew what of she wrote. Though truly bohemian she could also be a good housewife and mother. That she ended her life as a Blue Mountains widow, Mrs Bernie Wright, then it was in the sight of God and her neighbours. Her publishers and fellow writers knew she and poet David McKee Wright, literary editor of the Bulletin, simply cohabited. Mary Gilmore for one was unimpressed, particularly at the amity between Wright and his two Australian families (he had left a wife and son behind in New Zealand). Attitudes change: today it seems remarkably fair-minded and progressive.

By the time Cross published Songs, she was a single mother working as an actress and journalist. The need to earn a living persisted, her existence being usually precarious. When she met McKee Wright after a long correspondence, the attraction was instant and total – here was a kindred soul and poet of similar ability. It did not help that he was twenty years older and had an existing common-law relationship, with a large family. She had two children with Wright, before he died when their youngest was only four years old.

That the Wright-Cross menage was financially viable – if shaky – was due to George Robertson. The publisher might dominate Australian letters, but his market was small. Overseas success remains necessary for a writer to survive without a day job, then and now. Robertson was personally involved with his authors, which meant lending them money, including for McKee Wright to buy property, a haven for his new family. Famously Lawson sponged off him for years, becoming a burden; and Robertson came to feel similarly about Zora Cross.

Because A&R left such full archives, it is possible to reconstruct Cross’s relationship with her publisher. She had formed the habit of selling herself and her work via letters as far back as Turner and the children’s pages. At heart was her need for connection with the like-minded, with lovers of literature. Authors do flirt with publishers, the currency being words. It is part of the game by which they get into print. Yet Cross was over-intimate and needy – now she would be hell on Instagram. Even before they met Wright admonished her for ‘winding her way into the sympathies of men’, showing that in his case it had been more successful than he liked to admit.

Cross wanted Robertson to be friend as well as publisher, an impossibility, for he was also a businessman. Declining sales led to rejections, and an abandoned anthology project. Cross regretted selling her copyright to Robertson (the canny Turner had retained hers) and felt he owed her money. The falling-out was bitter, for even when Cross was newly widowed, with three children to support on an uncertain income, he declared that he never wished to hear her name again.

Nonetheless, she survived, and kept writing. One chapter departs from the relationship structure, being devoted to ‘Bernice May’, a pseudonym used by Cross. Here she prefigures Niall’s own work by devoting feature articles in magazines to other Australian women writers, 38 in all. It comprises an invaluable biographical source, even if many are now forgotten. Moreover, it shows Cross’s versatility: she was adept at interviewing.

Unluckily for Cross, the market for poetry, so strong for her work and that of her contemporary C.J. Dennis, declined. Articles would not keep her household together, so she turned to novels, which might have appeared in magazines and even from London publishers, but were not her real forte. She made a career mistake, letting an interest in ancient Rome become an obsession, the result being a series of historical novels. They ate up her time and never appeared in book form. In the end she got a pension from the Commonwealth literary fund, sufficient for survival.

One problem for biographers is the inevitable dying fall of chronological progression. If strictly followed, it can cause a biography to lose momentum, especially in the later stages of a life. Final years are typically less eventful, unless the subject achieves belated success or dies on the gallows. Here Perkins’ form works in mitigation, with a new personality in each chapter to vary the mix.

The book itself is opened and closed by the relationship which made it: that of Perkins with Cross herself. She found Cross’s words in the archives of the Mitchell Library, and ends by visiting her grave. Putting yourself into a biography can be dubious, yet in this context it works. Perkins is never intrusive with the subject of her obsession. If she lacks the sudden laser insight into personality that Niall can provide, then that can only come with time and practice.

‘History will find me’, Cross told her daughter April, who passed it onto Perkins. She was absolutely right, even if it was herstory. One of Cross’s best poems ‘Books’, began with the words: ‘Oh, bury me in books when I am dead.’ In fact, the contrary happened: it is a book which exhumes her extraordinary life and work.

Works Cited

Debra Adelaide (ed.) A Bright and Fiery Troop (Penguin, 1988).

Martin Boyd, Brangane (Constable, 1926).

Anna Maria Bunn, The Guardian, 1838.

Zora Cross, Songs of Love and Life (A&R, 1917).

Ellen Davitt, Force and Fraud, 1865 (Mulini, 1993).

Mary Fortune, ‘The Detective’s Album’, Australian Journal 1868-1908.

Catherine Martin, The Incredible Journey (Jonathan Cape, 1923).

Sylvia Martin Passionate Friends (Onlywoman, 2001).

Brenda Niall, Mannix (Text, 2015).

— Seven Little Billabongs (MUP, 1979).

Arthur Upfield, An Author Bites the Dust (Doubleday, 1948).

— The Sands of Windee (Hutchinson, 1931)

Francesca Wade, Square Haunting (Faber, 2020)