Seneca argued that there ‘is no great genius without some touch of madness.’ This oft-quoted statement expresses a familiar cultural ambivalence: an abiding faith in creative brilliance that nevertheless frames that brilliance in terms of great personal sacrifice.

This vacillation between genius and madness characterises the tragic life story of Vaslav Nijinsky, undisputed star danseur of the twentieth century Russian Ballet. In his most famous roles as Petrushka, the Rose in Le Spectre de La Rose (1911), and as a slave in Le Pavillon d’Armide (1909) and Scheherazade (1910), Nijinsky pushed the dramatic and athletic possibilities of classical ballet to a new level and rehabilitated the historically negative image of the dancing male through a highly charged sensuality. In his choreographic works – The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du Printemps) (1913), Afternoon of a Faun (L’après-midi d’un faune) (1912), Games (Jeux) (1913), and Till Eulenspiegel (1916) – he rebelled against what were perceived to be the central tenets of his art: beauty, grace and technical virtuosity. He challenged the art form physically, conceptually and aesthetically. In the words of Lincoln Kirstein, writer and co-founder of the New York City Ballet, Nijinsky ‘murdered beauty’ for dance in the same way that Picasso did for visual art. His audiences either loved or deplored him, crowding theatres to watch the ‘God of the dance’ and then rioting in response. From Afternoon of a Faun’s final masturbatory shudder to the ménage a trois in Jeux (performed by two women and one man, though originally created for three men), Nijinsky created dance about sex. In The Rite of Spring, his most famous choreographic work, the Chosen One dances herself to death, making the ultimate sacrifice for the fecundity of the earth.

The notion that dancers must sacrifice themselves for their art is not new, nor is the performance of insanity on the stage. Nijinsky’s artistic successor, Rudolf Nureyev, observed that the audience could tell if a dancer had a normal life outside of their art. Nureyev and Nijinsky have been described as the two greatest male dancers of the twentieth century, but they are also known as two men who sacrificed everything for dance, including exile from company and country. Culturally, we have become used to placing dance at the nexus of brilliance, sacrifice, madness and death. Vicky Page danced herself to death in the 1948 film The Red Shoes, and only recently Natalie Portman tapped into our collective association of dancers with madness in Darren Aronofsky’s film Black Swan (2010), winning an Oscar for her portrayal of a dancer whose self-destruction is played out in obsessive training regimens and violent hallucinations. Some of the themes in Aronofsky’s film – hallucinations, sexual ambivalence, violent outbursts and controlling parental figures – may well have been derived directly from Nijinsky’s life.

Nijinsky confounded audiences who were unaccustomed to a dancer with such potent sex appeal – what Jennifer Homans, author of Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet (2010), referred to as his ‘fragrant androgyny’ – but his glittering career was ruined by a string of psychotic breakdowns, as well as his hasty marriage to a fame-hungry groupie, Romola de Pulszky. Eventually, he became incapable of differentiating the real world from his delusions. His diaries, written on the cusp of his psychotic breakdown and published in several forms since 1946, have provided rich source material for those trying to decipher the nature of his brilliance amidst the ravings of a madman. After nearly three decades spent in and out of mental institutions, he died in 1950 from renal failure – a consequence, perhaps, of undergoing more than 200 treatments of insulin shock therapy.

Even before he died at the age of 61, Nijinsky’s life and contribution to the development of twentieth century Russian ballet was being contested and heavily mythologised. Some of his peers and colleagues, such as composer Igor Stravinsky, ballet impresario Sergey Diaghilev, and choreographer Mikhail Fokine, devalued his artistic contribution in order to enhance their own creative reputations, and perhaps to punish Nijinsky for perceived slights and betrayals at a time when he was incapable of defending himself. For others, like Nijinsky’s narcissistic wife, Romola, mythologising him was a way to make money and to flatter herself with the reflected light of the ‘World’s Greatest Dancer’.

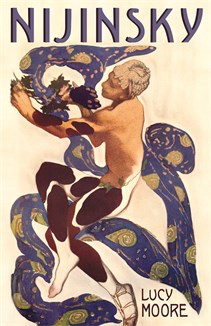

Lucy Moore’s Nijinsky is far from the first book to examine the facts of Vaslav Nijinsky’s sad life. Numerous dance writers and scholars, including Joan Acocella, Jennifer Homans, Peter Ostwald, Lincoln Kirstein, Ramsay Burt and Lynn Garafola, as well as Nijinsky’s own daughter, Tamara Nijinsky, and his sister, Bronislava Nijinska, have attempted to extricate Nijinsky’s legacy from these contradictory and equally misleading perspectives. In every case, the story of ballet’s spectacular leap from classicism to modernism in the early-twentieth century is presented in a way that recognises Nijinsky’s central role in the cultural transition. Moore’s book manages to be both the sum of the efforts of her predecessors and yet, somehow, significantly less than each of them. The point of Moore’s Nijinsky, it appears, is not to make a contribution to the knowledge of its subject (the ground has been well covered already), but to package ‘the Nijinsky story’ for a general audience, capitalising on the enthusiasm for the Ballets Russes and the renewed interest in Nijinsky’s contribution to Russian Ballet in the centenary year of The Rite of Spring.

Moore’s unsentimental, conversational text sticks closely to the life of the dancer. It makes for an enjoyable read, particularly as an introduction to Nijinsky, but the author skates over some of the scandalous details of Nijinsky’s life and some of the disturbing facts of his illness, many of which are highlighted in great detail in Peter Ostwald’s psychiatric biography, Vaslav Nijinsky: A Leap into Madness (1991). Compared to the extensive detail of Richard Buckle’s Nijinsky: A Life of Genius and Madness (2012), or the skill with which dance critic Joan Acocella navigates her way through Nijinsky’s story in her essay in Twenty-eight Artists and Two Saints (2007), or even the way Jennifer Homans situates Nijinsky’s legacy within the context of the development of ballet as an art form in Apollo’s Angels, Moore’s book is somewhat insubstantial.

Nijinsky was born around 1889 (the actual year is the subject of some speculation). He was the son of Polish itinerant performers and the second of three children. His strength and skill were apparent from a young age. He began learning to dance as a toddler, picking up skills from his parents, but also imitating the circus, tap and Cossack dancers who shared the stage with them. Nijinsky’s mother, Eleanora, had high ambitions for her children, and trained Vaslav to win a place in the competitive Imperial Ballet School, a position that virtually guaranteed him fame, fortune and, Eleanora must have hoped, a life of stability. Nijinsky’s younger sister, Bronislava, joined him at the school a few years later, and their close relationship enabled Nijinsky to cultivate his creative ideas – even more so than the many artists in Diaghilev’s inner circle. Bronislava – or ‘Bronia’ as she was called – served as her brother’s artistic muse through his most prolific creative period, assisting him in the creation of his roles in The Rite of Spring and Afternoon of a Faun, and helping him refine the artistic philosophy that underpinned his works. Bronislava’s ability to translate Nijinsky’s ideas physically, without the need for him to verbally explain them, provided him with a kind of artistic freedom; this was a creative collaboration borne as much from Bronislava’s technical abilities as a dancer and artist, as from her unwavering faith in her brother’s genius.

Despite the strict routine imposed on the students at the Imperial Ballet School, Nijinsky and his peers were not untouched by the violent political uprisings in pre-Revolutionary Russia and he found himself entangled in the Bloody Sunday riots of 1905. His early adulthood was also marred by a number of traumatic incidents, including the suicide of one of his favorite teachers, Sergey Legat, and his father’s decision to abandon the family to live with his mistress. Nijinsky experienced relentless and violent bullying at the hands of his classmates and, despite his demonstrable skill in the studio, he was an academic delinquent and found it particularly difficult to communicate verbally, despite excelling at mimicry.

Not content to be the proverbial ‘porteur’ for ballerinas, Nijinsky honed his classical technique, developing his leg muscles to achieve greater elevation – he appeared to pause mid-air – and creating seamless transitions between steps. It was a form of bodily conditioning his sister marvelled at and described extensively. Even before he left school, Nijinsky was appearing in Mariinsky programs and partnering celebrated ballerinas, such as Anna Pavlova and Mathilde Kshesinskaya, as well as rising stars such as Tamara Karsavina. Pavlova eventually refused Nijinsky as a partner, preferring to surround herself with less competent dancers rather than share her spotlight. This was one of the many small revolutions that characterised Nijinsky’s life and career, and served to distance him from his peers.

At the age of nineteen, Nijinsky abandoned his permanent position with the Mariinsky for Paris and Sergey Diaghilev. His relationship with the famous impresario was personal as well as professional. In fact, Diaghilev seemed to be incapable of distinguishing between the two. Nijinsky was far from the first dancer to find a wealthy, or at least well connected, protector. His relationship with Diaghilev was the kind of bargain for which ballerinas of the nineteenth century often hoped. In Paris, groups of wealthy men would ‘shop’ for dancers before and after their performances and offer an opportunity to trade poverty for a position as a rich man’s mistress. Kshesinskaya’s affairs with various members of the Russian aristocracy were legendary.

Like many biographers before her, Moore spends a great deal of time ruminating about Nijinsky’s sexuality. This is as much of a hot topic when it comes to Nijinsky as the discussion of his mental illness. Dance scholar Lynn Garafola has described Nijinsky as a ‘homosexual hero’ for his open relationship with Diaghilev, as well as a ‘homosexual turncoat’ for leaving Diaghilev and eloping with Romola de Pulszky. Moore points out that Nijinsky described sex with Diaghilev as a ‘sacrifice’ he made for great art. He may not have been an unwilling partner, she argues, but Nijinsky accused Diaghilev (in hindsight) of robbing him of his innocence and expressed guilt and ambivalence about masturbation and fornication. His obsession with sex ultimately transferred to his work onstage. His sexual orientation – gay, straight, bisexual – is a distinction that seems, from the outset, to matter very little, though Moore makes a case for Nijinsky’s heterosexuality. We know that he was involved with both men and women. But in her framing of the relationship between Nijinsky and Diaghilev as a sacrifice on Nijinsky’s part, Moore presents Nijinsky as a victim and offers an explanation for the dancer’s decision to embark on his disastrous marriage.

One of the most striking details about Nijinsky’s relationship with Diaghilev is the element of exploitation. They may have been lovers, but Nijinsky had no salary or contract for his work with the Ballets Russes as star danseur and, eventually, choreographer. Moore points out that Diaghilev offered Nijinsky room, board and protection in exchange for his work, and that for the older man this was probably a signal to the outside world of his commitment to the relationship. Diaghilev was continually begging for funds to keep his company afloat, and this arrangement was one of many bargains struck in the name of great art. But Diaghilev was not satisfied with having financial control over his lover. He arranged for a valet to spy on Nijinsky and report back whenever it seemed that another person (man or woman) was getting too close. In hindsight, one could argue that the ‘spying’ valet also served other important purposes – keeping an excitable Nijinsky calm and organising the mundane details of offstage life that Nijinsky found himself unable to manage. As Ostwald notes in Vaslav Nijinsky: A Leap into Madness, the dancer had already been diagnosed with a mental illness before joining the Ballets Russes and his emotional instability was recognised by those who worked around him.

As a dancer with the Ballets Russes, Nijinsky created some of the most iconic roles of the era. Together with Diaghilev, choreographer Mikhail Fokine, Igor Stravinsky, and designers Nicholas Roerich, Leon Bakst and Alexandre Benois, Nijinsky cultivated an association between ballet and ‘Russianness’. This ‘Russian ballet’ was born and thrived outside of its mother country, often drawing inspiration from Russian culture, as is so clearly the case with The Rite of Spring. Diaghilev and his successors continually looked homeward for new talent to enter the fold. Later, as non-Russian dancers began to join the company and its offshoots after Diaghilev’s death, the names of dancers would be ‘Russianised’ to retain the sense of glamour and exoticism.

Nijinsky eventually replaced Fokine as Diaghilev’s preferred choreographer. This decision was to have lasting consequences. After Nijinsky’s expulsion from the Ballets Russes, Fokine prevented his former rival from finding employment with the company as a term of his contract. The contrast between Fokine’s choreography in works such as Les Sylphides, an abstract ballet that paid homage to the elegance of the Romantic era, and Nijinsky’s brutal, rhythmic, highly sexualised choreography was on full display in 1913 when Fokine’s Les Sylphides was programmed immediately before Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring. Diaghilev could not have found a better way to highlight the chasm between young and old, between dance that paid homage to its classical roots and dance that rejected them, than by presenting these two works side by side.

The break between Nijinsky and Diaghilev is legendary and, in true Diaghilev style, the personal break-up necessitated a professional one as well. Moore hits her stride with her descriptions of the conniving Romola de Pulszky’s premeditated stalking of Nijinsky. Despite having no shared languages, the couple eloped to South America – far enough from Diaghilev’s grasp to make their union possible. As a result of this marriage, but also because Nijinsky was a notoriously slow choreographer whose works were not immediately embraced by the public, Diaghilev fired Nijinsky from the Ballets Russes. The decision was both personal and pragmatic for Diaghilev. The Ballets Russes would continue with other choreographers – Léonide Massine, Bronislava Nijinska and George Balanchine – but for Nijinsky it was the beginning of the end. Despite his efforts to assemble a company and create new work, the loss of a structured environment resulted in one disaster after another. His attempt to rejoin the Ballets Russes was subverted by Fokine and he was sent on tour to make money for Diaghilev, rather than being reincorporated into the company. In 1919, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Ostwald believes that Nijinsky would today have been diagnosed with a ‘Schizo-affective Disorder in a Narcissistic Personality’. His mental state deteriorated and he was eventually institutionalised, spending long amounts of time in Switzerland. Unable to perform publicly and barely able to communicate coherently, he completely withdrew. Although his death was mistakenly reported several times, he died in 1950 in London. His grave is in Paris, adorned with a statue of the dancer in character as Petrushka, the tragic puppet with a soul.

Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring is the work that has come to symbolise the cross-disciplinary collaboration of Sergey Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, as well as the moment that Russian Ballet became the pre-eminent expression of twentieth century modernism. Performed only eight times after its premiere on 29 May 1913, it has spawned its own mythology. The so-called ‘riot at the rite’ (the title of a 2005 BBC drama starring Adam Garcia as Nijinsky) was not a riot in the traditional sense, but rather a ‘riot’ involving outrageous theatrical behaviour. According to reports, audience members heckled the dancers, laughed loudly, booed or cheered, called out for the police and, according to one eyewitness, brandished their canes in the air in response to the heavy, inverted stomping of Nijinsky’s choreography and Stravinsky’s dissonant score. Nijinsky reportedly stood in the wings, shouting cues to the dancers over the din. The reaction was probably not entirely unexpected: Diaghilev had instructed both the cast and the orchestra to keep performing, no matter what distractions arose.

Seven years after the Russian Ballet’s last performance of Nijinsky’s version, Diaghilev commissioned a brand new Rite of Spring that retained Stravinsky’s iconic score and Nikolas Roerich’s costumes and designs, but featured less objectionable choreography by Léonide Massine, Nijinsky’s replacement in both Diaghilev’s company and bed. In the years since, creating a new version of Nijinsky’s masterwork has evolved into its own ‘rite’ of passage for choreographers. Martha Graham, who performed the role of the Chosen One in the Massine production of 1920, Pina Bausch, Maurice Béjart and Akram Khan are among the artists who have created a version of Rite. From the 1970s, performances of ‘Vaslav Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring’, reconstructed by dance historian Millicent Hodgson, have been regularly performed by companies including the Joffrey Ballet, although in the absence of original film footage with which to create her reconstructions, we must take the Hodgson body of work with a rather large grain of salt.

Moore is not terribly interested in this post-Nijinsky legacy of The Rite of Spring or even the posthumous legacy of Nijinsky himself, which is significant. She focuses on the man himself, attempting to evoke a sense of the person behind the labels of genius and madman. Although Moore’s Nijinsky is merely one of many books about this troubled, brilliant man, it is nevertheless a reminder that Nijinsky’s story resonates for a reason. The issues that his story brings to the fore – the nexus of genius and madness, the perception of dancing men onstage, the performance of sexuality – are still very much part of our conversation about dance today.