In my early years as an undergraduate, I sat in a lecture theatre for one of many courses on women’s writing. I was a naïve deaf girl from the country and these classes set my mind fizzing. That mild, autumnal morning, I sat up straight, waiting for the lecture to start. The lesson that came, with my lecturer’s dry humour, was about the wandering womb – the notion that women’s hysteria was caused by a womb that detached and moved around the body. Its history stretches back to the Eber Papyrus, an Egyptian medical record from around 1600 BCE, which explains that to ‘cure’ a patient, the uterus needed to be lured back to its rightful place through the administration of pleasant smells near the vagina, or feral smells near the head, forcing it down. In ancient Greek, womb and word were yoked – the Greek word for ‘uterus’ is hystera – and Greek physician Hippocrites first used the term ‘hysteria’ in the fifth century BCE. He suggested that the sexually frustrated uterus caused symptoms of anxiety and suffocation, while another physician, Aretaeus, described the womb as ‘an animal within an animal’. To marginalise women – particularly recalcitrant women – these physicians deemed their bodies faulty, unreliable and irrational, and set up a contrast to their coherent male counterparts. In my lecture, I snorted with disbelief at such absurd ideas and assumed they remained in history books, like dust bunnies behind a bathroom door.

Katerina Bryant’s Hysteria disabused me of this assumption. The book opens with the author in a grocery store with her partner, her movements and mind slowing. She feels as if ‘my bones have been taken out of me.’ Although she has lived with anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder, an agitation from being in the world and grappling with it, this, and other episodes, take her out of it altogether. She is unable to recognise her street: ‘the Penguin-crime paper-back green of my fence was not mine. My hands and forearms did not resemble my own, either. I would drift in and out of living with no sense of place, or self, to tie me down’. She has been evacuated from self, body and home, all elements which provide security.

Early on, a psychiatrist suggests that Bryant’s experience of unreality is an experience of ‘depersonalisation’. The term emerged in the writing of Swiss poet and philosopher, Henri Frédéric Amiel. In a journal entry published posthumously in 1884, Amiel described himself as ‘outside my own body and individuality; I am depersonalised, detached, cut adrift.’ In 1952, depersonalisation was listed in the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) under the heading ‘Dissasociative reaction’. This was a condition which had formerly been classified as type of ‘conversion hysteria’ in which (as suggested by Freud), repressed emotions manifest as physical symptoms. From the beginning, Bryant’s condition is connected with a history of the purportedly unruly female body.

Through a series of investigative chapters, Bryant interleaves her search for an explanation of her symptoms with the lives of four other women who encountered hysteria. Not only does she ‘try to read [her] way to an answer’ through these women, she contemplates how they have been written about. Her book is, in a way, a rewriting of Freud’s Studies in Hysteria, a series of five case studies of women diagnosed with hysteria which he co-authored with his mentor Josef Bruer. Bryant, reading through the lines of male-authored accounts, shows how some of these women have been stripped of their subjectivity, and attempts to restore it through her own words.

Bryant weaves her observations of her depersonalisation with the work and fortunes of Edith Jacobson, a Jewish woman born in 1897 in Chojnów, Poland. Edith studied psychoanalysis, became a physician and worked with the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute. In October 1835 she was arrested by the Gestapo and sentenced to two and a quarter years in the brutal Jauer Women’s Prison. When she fell ill with a reactive thyroid condition and diabetes, she managed to escape, recover and emigrate to New York, where she lived for forty years, building a ground-breaking career in psychoanalysis. Edith’s interactions with female prisoners exposed her to instances of depersonalisation, which she had not encountered in previous patients. She thought the condition might be prompted by the trauma of arrest and ‘the feeling that “this could not possibly have happened to them.’”

Bryant splits from herself as the women in Jauer did. When she has an episode of what seems like depersonalisation, she writes, ‘I’m gone’. Reality recedes and she is caught in ‘a disintegrating present’. It must be said, experiences of the prisoners do not match her own completely, for she has not encountered the same trauma. She continues investigating. After a clear CT scan, she is told that she might have pseudoseizures, or ‘psychogenic non-epileptic seizures’ (PNES) which resemble seizures, but without the electrical charges associated with epilepsy.

Bryant’s research uncovers the affecting story of 14-year old Mary Glover, located in the writing of physician Steven Bradwell. In 1602, Mary was troubled by fits, low vision and an inability to eat because her throat closed over, symptoms that were apparently provoked by her neighbour, Elizabeth, who thought her a poor influence on her daughter and locked Mary in a room. With a worsening condition, Mary prayed to the Lord for release. She described her circumstances as ‘Goliath’, but her adversary was not just her seizures, it was also an authority that, in late Medieval Europe, associated seizures with the devil. Mary believed her sinfulness was the cause of her illness, and was subjected to an exorcism. Bryant, contemplating Bradwell’s description of the waves of Mary’s illness, wonders ‘[h]ow much of this document is her and not him?’ She reads through his lines to see ‘just a young girl seeking comfort, unsure of how to live through the deep pain of her circumstances’. She offers an alternative reading of Mary’s condition, one that shows her managing not only the physical difficulty of her illness, but also the damage of ‘professional’ opinions.

Bryant revisits this idea – the mediation or authorship of women’s bodies by men – in her account of Katharina, a case study in Freud’s Studies in Hysteria. Katharina approached Freud on a mountain climb after she saw his name in the visitor’s book of her family’s resting hut. She sought a solution to episodes in which her throat squeezed and her head hammered ‘enough to burst it’. Freud traces Katharina’s ‘acquired hysteria’ to an uncle’s persecution after she caught him sexually abusing her cousin – but after the publication of Studies in Hysteria, he stated that this case was not clinically valid. Bryant laments that the female voice is, once again, overwritten: ‘All that is left of [Katharina] is on the page and she wrote none of it. They are Freud’s words’. When Bryant wonders ‘whether Freud was capable of writing [Katharina] as she was, and not as he hoped her to be’ she leaves, as with Mary, a space for re-imagining this woman’s self.

Bryant delves into these women’s lives according to her research into her symptoms. Each new diagnosis, or possible diagnosis, is a springboard to a new era, be it the 1930s in Germany, Sixteenth Dynasty Egypt, the early seventeenth century or the late nineteenth century. This movement makes it difficult to grasp the historical progression of hysteria in the book and to understand its relationship to other disorders. Perhaps clarity is impossible, as Bryant acknowledges via psychoanalyst Neil Micklem’s The Nature of Hysteria, ‘Hysteria is protean: a multi-faced disease presenting such a wide variety of appearances that it has earned the reputation in some circles of being an absurd ailment with a fair proportion of incomprehensible symptoms’. Despite this, stereotypes of the illness persist and, Bryant writes, ‘even today, when hysteria is mentioned, an image of a shaking, manic woman comes to mind’.

Kylie Maslen, in her essay collection Show Me Where it Hurts, contends with this stereotype as she manages the chronic and often overwhelming pain of endometriosis, as well as bipolar disorder and depression. Her health conditions revolve around her reproductive system, and her frustrations with medical professionals recall the egregious assumptions of the wandering womb and hysterical women. She cites a 2001 paper, ‘The Girl Who Cried Pain,’ which reports that ‘doctors widely – incorrectly – hold the belief that because of a biological make-up designed to withstand childbirth, women have a natural capacity to withstand pain. As a result, women wait sixteen minutes longer than men to receive pain relief in an emergency, and when they do receive pain medication it is 13 to 25 per cent less likely to be an opioid’. Fiona Wright, in her recent essay ‘I Need my Literature to Know About It’, refers to this as ‘medical gaslighting’. It stems from a lack of trust in women’s ability to ‘understand or narrativize their own bodies, because it has for centuries doubted the rationality of creatures surely ruled by their wombs’ and because the male body has, for so long, been taken as the standard. When Maslen speaks up about the decline in her mental health, she’s told:

it’s just the pain playing tricks with my mind. When I have begged for help to treat the physical illness at its source, I have been questioned about my reliability (‘it’s probably just hormones’), about the severity and frequency of my pain (‘it can’t be that bad’), and about the need for medication (‘just take some Panadol and see how you feel’).

A lack of faith in the way women write and speak about their bodies means, for Maslen, a longer wait time for help, during which she self-medicates with painkillers and alcohol.

It also means frustration with the constant re-iteration of the impact of chronic illness. Maslen’s opening essay, ‘I’m Trying to Tell You I’m Not Okay’, dwells on the difficulty of expressing pain, particularly to ‘normies’ (people who do not have a disability or chronic illness) who do not listen or try to empathise, or to medical professionals who rely on pain charts. Rather than words or charts, Maslen prefers memes for communicating how and where she hurts. Memes ‘articulate what’s going on in my head better than my abrupt and stuttering messages to loved ones. I don’t have to find the words. Memes have them for me’. Memes don’t require face-to-face communication, and are used by people with chronic illness ‘to let each other know they’re not alone, to convey a complex empathy that is nonetheless accessible and simple to understand’. They save energy and provide comfort.

While there is a clear benefit to memes, it is puzzling that Maslen should open a book with an essay that decries the limitations of words for describing her pain. The later essays in the collection undermine this claim in their articulate evocations of bodily experience. In ‘A Playlist for the Love Sick’ she describes a body shaped by hormones, medication, surgery and scars as ‘a gateway to be explored with hands and mouths’. It is a body that informs her choice of sexual partners, sidestepping the ‘heteronormative blueprint of “success”’ and reaching instead for ‘people who are divorced, who have kids, or anything else that can scare others off in the finicky world of online dating’. It is a body that seeks sensuality at the same time that it is subjected to a barrage of invasive medical scans and procedures. It is a body that might yield the unexpected.

During sex, the first time since a bout of surgery, with a guy who loves football, Maslen feels ‘a pop and a rush’ and begins bleeding. An ultrasound, pap smear, cancelled dinner date with the football fan, colposcopy, hundreds of dollars and (undoubtedly anxiety-fuelled) hours later, Maslen saw the boy ‘outside a football stadium and tried to make myself invisible’. These encounters require an assessment of how Maslen feels, physically, mentally and emotionally, for even if sex is enjoyable, there is a risk that her body may respond with pain rather than pleasure. She learns to hold onto these moments of ‘glow flushed through my body’, storing them for a time in the future when she will be ‘desperate for a reminder of joy’. The intimacy in this essay, both between Maslen and the football fan, and between her body and the reader, paints a clear and detailed picture of how pain shapes her actions. Words do not seem limiting here; rather, they are a portal into her lived experience.

Where Bryant turns to literature and history to understand the permutations of hysteria, Maslen turns to popular culture. Her fourth essay, ‘The Fetishisation of Frida’ opens with a description of taking a selfie of herself in a hospital bed, echoing the practice of artist Frida Kahlo. When Kahlo was 18, a bus collided with the streetcar trolley in which she was travelling, leaving her with multiple fractures from her clavicle to her feet, a crushed right foot, dislocated shoulders and ankles, and a foot and pelvis impaled by the trolley’s metal handrail. Immobilised in hospital, Kahlo painted self-portraits using a mirror suspended over her bed. She created images that drew upon her pain, and showed her resilience in the face of it.

Popular and contemporary representations of Kahlo’s life however, have been simplified, and her body’s neuropathic pain, her surgical corsets and the discrepancy in her leg length, are elided. This is epitomised in a bracelet worn by the British conservative Prime Minister Theresa May which featured a cropped and altered version of Kahlo, one that stops at her shoulders so that her disability is hidden, lightens her skin and darkens her lips. The disability that engendered her art is forgotten. It is an overwriting of her story that, as with Bryant’s subjects Mary and Katharina, denudes them of their subjectivity.

While expressing the nuances of living with disability, or chronic or mental illness, is a major component of these books, it is not the only one: they each also work to define a self that does not conform to the traditional, autobiographical subject. Linda Anderson notes in her survey of autobiography that, from the genre’s inception until the mid-twentieth century, it denoted ‘a unified, unique selfhood which is also the expression of human nature’. This understanding of selfhood also underpinned the ‘centrality of masculine – and, we may add, Western and middle class – mode of subjectivity’. The waves of intellectual and social movements which followed modernism – feminism, query theory, disability studies, poststructuralism, postmodernism and ecocriticism – have each contributed to the dismantling of the idea of this singular, coherent subject. In writing as chronically or mentally ill women, Maslen and Bryant forge new ground.

Maslen is apprehensive that ‘with every day that passes I become more my pain and less myself. That with every storm that turns my nerve endings to fireworks, every walk along the beach that goes too far and becomes exhausting, and every bad reaction to inflammatory food, I lose more of me.’ These moments, in which the body eclipses the conscious self, are threatening and dismaying, but they open a door to something more interesting and relevant than the unified, self-contained self. As Maslen explains, ‘Chronic pain and chronic illness do not fit into neat narratives – either personally or medically,’ and the episodic structure of Show Me Where It Hurts reflects the relentlessness and recursiveness of chronic illness.

Bryant writes that Freud’s patient Katharina ‘is an image of my great fear. One greater than seizures pulsing through me each day. A fear that leaves me as just an idea of hysteria. Not a body, not a person, but a case number to be read and considered’. At the same time, she recognises that withstanding this fear has benefits: ‘To come out of depersonalisation is to feel connected to yourself. It’s hard to worry about the shape of your nose or the ballooning of your belly when just recently you were convinced you were an alien. Perhaps to know the extent of your own resilience, fully, is an experience to be cherished’. In her final chapter, in which she features as her fifth case study, she finds a psychologist who helps her accommodate her temporary disappearances, and her terror about her seizures begins to fade. She acknowledges the importance of writing in this process:

Writing my life down as I became unwell helped; I could not speak this illness aloud but I could write it. I don’t know what it’s like to be ill and not have a voice. Mary, Katharina, Blanche spoke in ways that meant they were ostracised. To be punished for being ill, when this illness is already so punishing, is a hardship that I can never fully fathom.

Maslen also writes to control the chronicle of her pain, not only on the page, but on her body – with tattoos. In ‘Scar Tissue’ she describes the erratic and unexpected pain her body can cause: endometrial tissues in her pelvic cavity that bleed, clusters of cysts in her ovaries that can burst, pain signals from her pelvic nerves that fire ‘at the smallest breath of cold air’. But the external pain that comes from a tattoo is one that she controls. It’s an inscription and symbolic representation that she chooses.

These acts of agency are now available to some women in a way that they were not in history. Bryant’s penultimate subject – Blanche Wittmann, known as the ‘Queen of Hysterics’ – is captured in Andre Brouillet’s painting A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière (1887). A limp woman, her hand twisting back in a seizure, is held by a doctor, while a female servant looks on, her body taut with anxiety. Meanwhile neurologist Jean Charcot lectures to a public audience of avid male onlookers about Blanche’s condition. This image encapsulates the histories of the figures Bryant describes: sensualised curiosity, power imbalances, and an inability to speak their own conditions. This is particularly pronounced in Blanche, upon whom Charcot experimented with dermographism, or inscribing on patient’s skin. Their ability to take on these inscriptions ‘was believed to be evidence of “extreme suggestibility”’, according, as Bryant writes, to philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman.

Yet Blanche was not a passive tablet. Bryant’s account recognises her force, and that she performed her seizures to maintain her stay – and safety – at the Salpêtrière after years of persecution and abuse. These are bodies that, in difficult circumstances, find power where they can.

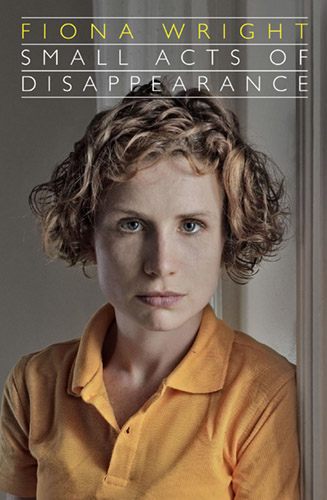

The lecture that amused me in the mid 1990s; Bryant’s search for women in stories by medical men; Maslen’s attempts to communicate the depth, breadth and shade of her pain. Women’s bodies are still seen as erratic and unreliable, as are the voices that delineate those bodies. Yet over the past few years, an increasing number of female writers have articulated their insights into chronic illness: Fiona Wright’s Small Acts of Disappearance and When the World Was Whole, Jacinta Parsons’ Unseen: The Secret World of Chronic Illness, Libby Trainor Parker’s forthcoming Endo Days, Kate Middleton’s essay ‘‘The Dolorimeter’ published in the Australian Book Review, and Lucia Osborne-Crowley’s I Choose Elena.

For people with disability, or chronic or mental illness, connecting with these stories is like grabbing a thick rope in a choppy sea, as Bryant writes, ‘[r]eading about illness is such a comfort. Seeing my symptoms and experiences reflected back to me assures me I am not alone. I am not irreparably broken as I fear, but share an experience with another person.’ Reading, or connecting via social media, memes and hashtags as Maslen does, creates community. In a culture which diminishes people with disability and chronic illness, these gatherings of words or images help us to see ourselves not as deficient, but as creative and resilient.

Bryant and Maslen’s books, committed to redressing the faulty historical record on women’s suffering and pain, are a corporeal rebellion. They lay bare the exhaustion occasioned by capitalism’s resource extraction, the unyielding walls of our workplaces and institutions, and the misogyny, latent or overt, of medical practice. In writing of their chronic and mental illnesses, the authors rupture the narrative that a successful body is a well body, and open a space for new and original accounts of how those bodies mediate the world.

Works Cited

Anderson, Linda R. Autobiography. Routledge, 2011.

Wright, Fiona. ‘I Need My Literature to Know About It.’ Sydney Review of Books. 14th August 2020.