To cross a line can be to start something – a race or a journey – or to breach a boundary. It can also mark a disruption or a transgression. In her new memoir, Position Doubtful, Kim Mahood crosses many lines. She broaches topics that are fraught with ethical, social and intellectual complexities, and while she does so with a confidence earned through experience, she does not relinquish her uncertainties. She questions herself, her right to be doing what she does, her reactions to people and to her situation as a white artist working with Aboriginal people. With compassion, wit and elegance, Mahood takes us to a landscape known by white people only as a barren and alien place of no value – except to mine for minerals. She shows us another way to look at it, through the eyes of the traditional owners as well as the perspective of an artist. ‘What drives me,’ she writes, ‘is not a desire to help, to fix or change, but to understand something about my country.’

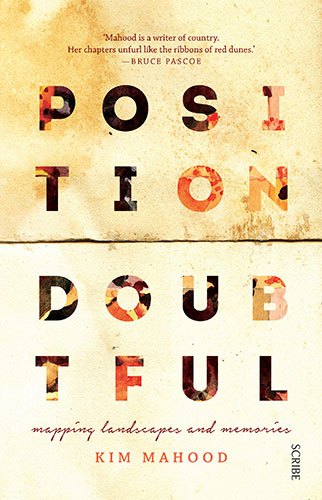

Mahood’s first book, Craft for a Dry Lake (2000) won both The Age Book of the Year award and the New South Wales Premier’s Prize for non-fiction. In it, Mahood told the story of her childhood, how her parents built a cattle station they called Mongrel Downs (‘a mongrel of a place’) in that vast, sparsely populated country that stretches across the Northern Territory border in to Western Australia. She mentioned ‘position doubtful’ in that first memoir, words she found on a map owned by her father, which she kept, not realising that maps were going to become so important to her. The map became a metaphor not just for where she found herself geographically, but also emotionally and ethically.

At the end of Craft for a Dry Lake, Mahood wrote:

I do not have to go on wearing the identity I have created for myself. I can decide whether or not to begin to spend the time to build up a relationship based on the reality of this place as it is now, and the people who live here now. Or I can leave it behind.

She did not leave it behind. The second memoir picks up the story and her quest for the ‘reality of this place’ and to find conjunctions between the way Dreaming stories and science respond to the landscape. In the new memoir Mahood explains how her project produced a ‘cognitive shift from which I will never entirely recover’. Position Doubtful requires the reader to make a similar shift.

Position Doubtful’s subtitle is ‘mapping landscapes and memories’ and the book’s cover is a muted, ambiguous design based on one of Mahood’s mapping artworks. She begins by recapping the 1992 journey she made back to Mongrel Downs, now called Tanami Downs.

Tanami Downs is about 700 kilometres north-west from Alice Springs along a track that is often impassable. The Central Land Council records that the station was returned to traditional owners in 1992 and describes it in this way:

Although droughts are regular, the station has some mountainous areas with permanent water and the central and northern portions are good plains covered with ‘neverfail’ grass, claypans and lakes, providing the basis for the cattle operation.

The business set up to run the station with traditional ownership and pastoral advisers went into liquidation in July this year, so it looks like it will no longer operate as a cattle station.

If you have a romantic notion of outback travel, this book will sober you up, although it isn’t one of those ‘you’ve got to be as tough as I am to do this’ memoirs. Mahood is not an adventurer, nor is she fascinated by the hopeless explorer narratives which have inspired writers such as Patrick White or, closer to her own time and experience, Nicolas Rothwell. Allan Arthur Davison is her man. Contracted in 1897 to survey the Tanami for gold-bearing potential, Davison’s competence is admired by Mahood. She compares him favourably with many diarists who, like journalist F.E. Baume, saw the region as a ‘horrible desert’ and the inhabitants as ‘treacherous and unstable’.

In 1996, Mahood was back in the Tanami on a camping field trip with her friend, the artist Pam Lofts. Both women were working, in different ways but also together, to translate into art what they were seeing in this extraordinary landscape. She made several camping trips after that, until, five years later, she was in Balgo working for her board and keep at the Warlayirti Art Centre. She had decided she needed to do more than camp for short periods in almost-isolation along the string of lakes:

I needed to go back to the source, to spend time among the people whose culture had been shaped by the desert, whose minds and bodies were the product of thousands of years of adaptation.

Mahood’s visits to these communities often coincide with sorry business, described with unfussy empathy that very much assists a reader for whom these customs are difficult to understand. We meet Ngardi people, including Dora, her daughter Margaret, and Margaret’s daughter Patricia. A similar empathy is extended to the kartiya (white) workers in the community. Mahood uses all her life’s experience to describe and analyse people with kindness, understanding and critical assessment– sometimes choosing an anecdote, sometimes a detail from a conversation, or making a summation.

In Balgo, she develops her own visual understanding of the landscape, watching and assisting the work of Aboriginal artists, such as prolific and sought-after Eubena, and Lucy Yukenbarri, whom Mahood helps complete a women’s mosaic at the entrance to the art centre. Sharing and talking with people about historical maps of the region, she begins formulating ways to create maps that will ‘reveal common ground between white and Aboriginal ways of representing and understanding the country’.

And so, when she is invited back to the region to help set up a women’s refuge and culture centre, she decides to go, even though she still hesitates at that stage because ‘women’s business wasn’t my thing’. The Walmajarri community at Mulan is smaller than Balgo and the right base, Mahood decides, to develop her plans for this mapping project.

During this time she heads out to one of the important sites for traditional owners at Lake Gregory with a large group that includes the geomorphologist Jim Bowler, famous for his work at Lake Mungo in the 1960s, which dated occupation of Australia back 40,000 years. Traditional owners – such as Bessie (married to Bill Doonday, mother of Shirley Brown) and Charmia Samuels, Bessie’s sister Lulu, as well as Monica and Evelyn, widows of Walmajarri men, but both from elsewhere – are gathered to record the oral history and Dreaming stories of the sites they visit.

These language groups, networks and affiliations are sometimes hard to keep track of, but it is important for the white reader to understand how the protocols are delineated and why they matter. On the visit to Lake Gregory, there is a powerful sense of purpose and achievement that comes through the account from both black and white perspectives. Mahood is both part of the action and an observer, instigator and follower, teacher and learner.

Many of the same people return later to camp again at Lake Gregory, this time specifically to try to date evidence of human occupation in the area. Mahood stays on and begins to work on paintings that she will later exhibit in Canberra. By this time, she feels as though the desert has become part of her, ‘as if in my trajectory across it I have absorbed it, and must now carry it with me’. She believes she finally understands the organising principles and the ceremonial aspects of Aboriginal painting, and simultaneously understands that she is forbidden to use them. She proceeds with caution, thinking about the use of grids and horizons in Western art, how the aesthetic element of the grid also aligns with the coordinates of the natural world, and how this relates to the human understanding of place, both in Western and Aboriginal cultures.

I draw the east face of the erosion gully on watercolour paper ruled into a barely visible grid, and paint what I see, one square at a time. Completed, the work spans three small sheets, the third panel consisting of a painted grid of feathery brush marks and dots. They’re not dots, I tell myself, they’re pisoliths [a word for very small stones, which she is delighted to learn from the archaeologists]. But there’s no question that I’m dotting the grid, a transgression I contemplate with alarm. As long as I keep the paintings small and unostentatious, maybe I’ll get away with it.

How many women have kept their art ‘small and unostentatious’ in order to get away with doing something not expected or allowed of them? ‘No one seems to notice that I’ve crossed a line,’ she says when she shows the works. ‘The contradictions, the doubleness, was where the charge lay’, she says, capitalising on the ambiguity of the word ‘charge’ to underline what is at risk. Is she getting away with this because she is a woman, and therefore more able to slip under the radar of cultural judgement? Or is she getting away with it because she is in a position that is possibly unique: she has been born white in the country she is now painting, but is vitally aware of its Dreaming history as well as its recent history, the lives of the region’s Indigenous people and their Ancestors’ stories. She does not have the kind of kartiya anxiety about weighing in on debates around the current state of Australia’s Indigenous populations for fear of sounding patronising or ignorant.

‘Partly it’s about being exposed to minds wired during pre-contact childhoods,’ she writes – not her most elegant sentence, but one that shows how tentative is the language we have to talk about why some white Australians are fascinated by black culture.

Partly it’s about believing that we all had that capacity once, that the physical attributes of place were among the earliest factors to shape the human mind … It’s about wanting, as a white Australian, to find a vocabulary to tell as best I can the story of a place.

So this is not about ‘becoming black’, but about opening her white Australian mind to the experience of those whose ancestors lived in the inland. She is writing at a time when the racist essentialism that marginalised Indigenous cultures is being slowly overturned. A reverse essentialism that privileges the spirituality and ways of seeing of pre-settlement Aboriginal people may be a necessary corrective to the ignorance we read about in historical accounts, but Mahood’s position may be what comes next: Position Doubtful suggests a way forward, beyond us-and-them, based on sharing across cultural boundaries.

Mahood thinks this puts her ‘out of step with the intellectual and academic temper of my time’:

I could not submit to the reductionism that always seemed to place me in the role of a colonial usurper. It was more complicated than that, and always had been. Aboriginal people had always had more agency than such an interpretation allowed. And I knew white people who felt for the country as deep an emotional and physiological attachment as the traditional custodians, and were more like them in their social and psychological temper than they were like urban Australians of any race.

Mahood’s ‘unique set of circumstances’ make it possible for her to state this case for a less dichotomised understanding of black-white relationships. She frames this with her doubts about the validity and the practicality of years and years of work: ‘I wonder what I’m doing,’ she writes, ‘whether any of it amounts to anything, and how I can hope to sustain it, both financially and physically.’

We are reminded that the decision to head off from her base near Canberra in her Toyota with her dog and camping gear is not so much an adventure or even a vocation as a duty, driven by intellectual, spiritual and artistic needs. Those moments when Mahood necessarily walks the line between self-analysis and self-justification are a crucial part of this book, because they make it more than an essay about race relations, or a philosophical meditation on how ‘geography shapes who we are and how we think’, or an artist’s diary with poetic interludes. They help us know who she is and how she deals with relationships, as well as why she is out there in the Tanami and what she wants to achieve by it.

The girl we met in Craft for a Dry Lake was an androgynous figure, mixing it with stockmen, keen to make her father proud of her abilities. She refused victim status. She was more interested in understanding how the roles of both men and women were and still are restrictive. She first headed back to the desert country when she was in her forties, following the death of her father, and on that trip she stopped for a broken-down car on her way to the former family station at Mongrel Downs. She was amused by the way the two Aboriginal men accepted her help, then asked for more, then a little more, until she let them know she had reached the limit of her generosity. Later, she realised that a woman encountering two men in a remote place might be dangerous, and that her lack of fear was perhaps foolish and even racist: ‘…there is an element of “white missus” in my thinking, an assumption that we inhabit mutually exclusive worlds, which is a hangover from my past. I wonder if I would have stopped for two white men looking as disreputable. Probably not.’

This questioning of her own viewpoint, the ‘teasing out’ (a favourite expression) of the cultural and personal meanings of what happens to and around her, is instructive rather than confessional. In Craft for a Dry Lake, she was not ready to embrace women’s business but she did begin to realise that something has shifted since her childhood in the Tanami, a shift towards acknowledgement of the ‘importance of the black women’s relationship to their country’, brought about by ‘government funding and the involvement of white women co-ordinators (city girls for the most part, drawn by dreams and political ideals)’. This was a surprise to her at the time, and she realised, too, that the white stories about this part of Australia were written by men; where women such as Daisy Bates or Olive Pink came into the picture, it was as curiosities. Such women were part of a tradition which has ‘steadily gained momentum, that of white women aligning themselves with Aboriginal people as a means of freeing themselves from the conventions of their own society.’

Does Mahood include herself in this assessment? As a child, she was aware that women were marginal to the frontier story, rarely even mentioned in the account of the explorer Davison, or in her father’s diaries. She does recall, however, that her mother was ‘romantic and delighted in her child’s intense identification with this mysterious indigenous people’. Both mother and daughter cherished Kim’s association with the black women who helped look after her when she was an infant. ‘She felt a responsibility towards her own singularity which she took seriously into adulthood, fending off the spectre of ordinariness with this talismanic knowledge,’ she wrote in Craft. Is this observation of her younger self (in the third person, which Mahood explains is the only way she can get enough emotional distance) meant to gently mock her ambition? Is it another self-critical ‘white missus’ moment when she recognises her reliance on these desert women to create her own identity? Or is it an acknowledgement, pure and simple, of the debt she owes for being able to step into the mysterious culture of these desert people?

For the woman Mahood was in her forties, it was more of the former, part of her self-scrutiny. When we begin to hear, in Position Doubtful, the voice of that same woman almost two decades on, it is thrilling to witness her strength and assurance: how much she is able to share about her relationship with the land, with the Tanami people, and particularly with the Aboriginal women, who, in the intervening years have stepped forward such a long way from their position behind the men.

Her artist friend Pam Lofts, who was so important for Mahood both emotionally and artistically, used to take photographs intended to be a ‘feminist critique of the white male myth of exploration’, providing props for Mahood to dress up, and choreographing her doing things like dragging a small boat across a dry salt lake. Mahood was happy to take part, entertained by Lofts’ wacky exuberance, but their artistic interests drifted apart over the years. ‘I’m not quite done with the habit of exploring my own psychic baggage,’ Mahood says, ‘but I’m getting a little tired of it.’ Someone still worrying away at ‘anxiety and desire’ (which was the title of Lofts’ exhibition following their first two Tanami trips) might not have been ready for the physical and mental challenges of a project to find ‘common ground’ between people whose languages, memories and cultures seem so different. Not just this chapter but the entire book is a requiem for Lofts, who died in 2012. Her ability to acknowledge this deep, beautiful friendship, and other women dear to her, is moving. She also writes very well about dogs.

Much of the shape of this book relies on narrative description of Mahood’s work with both Aboriginal people and kartiya fellow-workers, so a reader might wonder how much was left out of Position Doubtful, and whether the privacy line is ever crossed. The final pages of the book recount one of her meetings with the Sturt Creek Yoomaries to talk to them about what she has written. For a long time, she says, she has been writing down their stories and mapping their country with them. ‘Now it’s my turn,’ she tells them. ‘I’m going to tell my side of the story.’ Working with several of the women on their artworks, she had noticed how incurious they are about her city life, or her reasons for being there with them, as though it is only their shared story that is relevant. One imagines, then, that the words Kim Mahood finds to describe this place she has spent so long in and finds so strange, beguiling and majestic, might also be superfluous for these people who know it in their bones. For those of us without that knowledge, this is an opportunity to benefit from this writer’s search for the language that will tell the story of place, and in the process help us understand the map of the human mind. The lyrical passages describing the landscape are inspiring.

The book begins and ends with Mahood taking part in sorry business, a constant reminder of the terrible mortality rate of the people in these dwindling communities. She is unflinching in her accounts of violence, illness, and incidents that are shocking and tragic. Not fully outside the community, nor claiming to be within it, she accepts her role as cultural go-between, in order to achieve what she believes is possible and necessary. She begins Position Doubtful by inviting the reader to think of the book as a map, ‘annotated by more than one hand’, and that is, indeed, the way it unfolds, scored and intriguing, beautiful and functional, old as the hills but with new discoveries. Mahood’s ability to allow contradictions to co-exist is magnificent:

This lake, where ancestral pathways cross and ancient waterways meet, is my point of entry and departure, the place where my two lives intersect before I step into whichever persona is needed for the task ahead. In the morning, I will walk across to the other camp site at the eagle tree and carry out my ritual of arrival. But for the moment I just sit, listening to whatever the silence has to say.