Once, French theorists tried to bury the author. In 1967, in a now famous essay, ‘The Death of the Author,’ critic Roland Barthes declared the author ‘dead,’ suggesting that the literary text was merely a ‘fabric of quotations’ – a dense weave of disparate borrowings, echoes, and recycled words.1 Two years later, philosopher Michel Foucault responded to Barthes’s dead author with his notion of the ‘author-function.’ ‘What is an author?’ anyways, he mused, and ‘What difference does it make who is speaking?’2

Despite French Theory’s claims to the contrary, the identity of the author, in the case of minoritized writers, has always seemed to matter. This is especially true of ‘Francophone’ writers – a designation that has long served as a byword for ‘Black’ or ‘foreign’ and frequently is applied to any Afro-descended writer working in French, even those born in France. In the history of Black authors writing in French – and in Mohamed Mbougar Sarr’s new novel, winner of the prestigious Prix Goncourt – it turns out that authorship matters very much.

In fact, in 1968 – a year after Barthes announced that the author was dead and cautioned critics against the pitfalls of confusing close reading with author biography – the French publishing world erupted in a literary scandal turned witch hunt, one that hinged almost entirely on questions of authorship and authenticity. For 1968 was also the year the Éditions du Seuil in Paris published a breakthrough novel by the young Malian writer Yambo Ouologuem, Le Devoir de violence (Bound to Violence), which won one of France’s most prestigious literary honors, the Prix Renaudot. A baroque and bloody history of an imaginary West African empire spanning the thirteenth to twentieth centuries, Ouologuem’s novel met with critical acclaim. Then it became embroiled in a controversy that has spanned multiple continents and several decades.3

Initially hailed as an African Proust, Ouologuem was soon denounced by critics as a mere plagiarist and charged with having stolen passages from writers such as André Schwarz-Bart and Guy de Maupassant. The English novelist Graham Greene even filed a lawsuit against Ouologuem and his publishers at Seuil, claiming that lengthy passages had been directly plagiarized from Greene’s novel It’s a Battlefield (1934). Seuil stopped production and removed the book from shelves; the novel was subsequently banned in France. (Only in 2018 has Le Devoir de violence been reedited and republished in French – the result of work by scholars in recent decades to rehabilitate Ouologuem’s reputation and clear his name, so to speak.4)

What happened next both mystified and maddened French critics: Ouologuem disappeared from public view, seemingly without a trace. Although he would go on to publish two more works in short succession, Lettre à la France nègre (1969; A Black Ghostwriter’s Letter to France) and an erotic novel, Les milles et une bibles du sexe (1969; A Thousand and One Bibles of Sex), under the pseudonym Utto Rodolph, Ouologuem ultimately decided to ‘wash his hands of writing in French,’ as Christopher Wise puts it.5 Ouologuem refused to state his case, turned his back on the French publishing world, and returned to Mali.

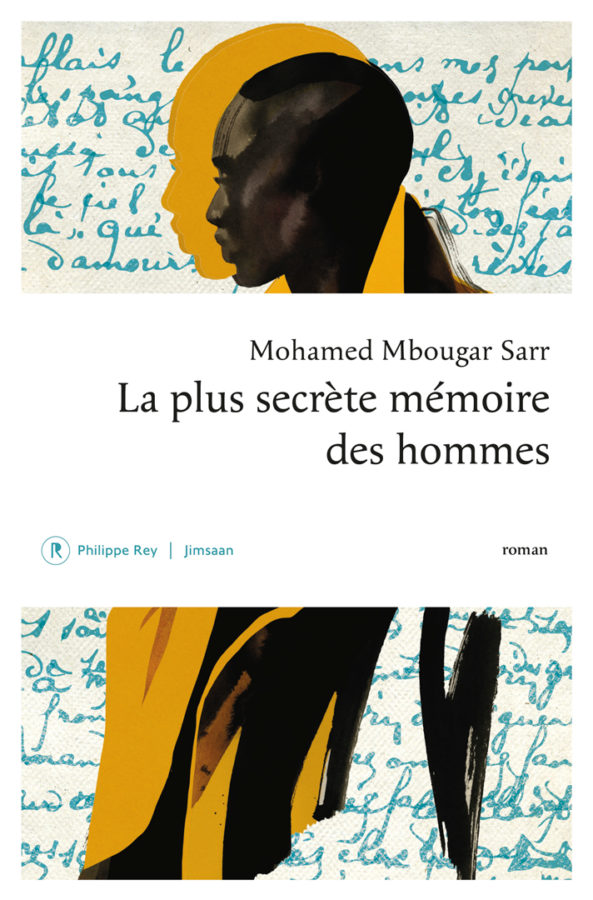

Now, a new novel has been dedicated to Yambo Ouologuem: 31-year-old Senegalese writer Mohamed Mbougar Sarr’s La plus secrète mémoire des hommes (2021; The Most Secret Memory of Men), which won the Goncourt last year. In it, Sarr revisits Ouologuem’s story to confront the racist history of France’s elite literary prizes, the parasitism and hypocrisy of literary criticism, and the ambivalent status of African writers working in former colonial languages within a global literary marketplace.

With his masterful novel, Sarr has done more than set ablaze the French literary scene. Ultimately, La plus secrète mémoire des hommes puts on trial French literary history itself.

In addition to the Goncourt, La plus secrète mémoire des hommes was long-listed for several other prizes, including the Renaudot, the Goncourt des Lycéens, and the Prix Femina. The Other Press has already purchased rights to the book in English. This is Sarr’s fourth novel and his second, after De purs hommes (2018; Real Men), published with the French imprint Philippe Rey. His first two novels, Terre Ceinte (2015) – translated into English as Brotherhood (2021) by Europa Editions – and Silence du chœur (2017; Silence of the Choir) both were published with Présence Africaine.

Sarr’s novel is a literary history cum detective novel about an elusive Ouologuem-like figure. Inspired by Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño’s novel about the search for an obscure poetess, The Savage Detectives (1998), it follows the peregrinations of Diégane Latyr Faye, a Senegalese novelist living in Paris in 2018 who stumbles on traces of a mythic text whose author remains shrouded in mystery.6 The manuscript, Le Labyrinthe de l’inhumain (The labyrinth of the inhuman), was published to much fanfare in 1938 by a certain T. C. Elimane, a young Senegalese student who became the darling of the French literary world before charges of plagiarism led to a very public fall from grace.

Hailed as a ‘Black Rimbaud’ (Rimbaud nègre) before being condemned as a fraud, Elimane (whose real name, we learn, is Elimane Madag Diouf) emerges as a clear historical double for Yambo Ouologuem. But his story also bears similarities to the Antillean writer René Maran, the first Black writer to receive the Goncourt. In 1921 – exactly a century before Sarr’s win – Maran was awarded the Goncourt for his novel Batouala: veritable roman nègre (1921; Batouala: A True Black Novel), which was subsequently banned for its harsh critique of French colonization.

In La plus secrète mémoire des hommes, Diégane searches for traces of Elimane and his manuscript, a text he first encountered as a child in the form of a citation in an anthology of Black African writers. His quest leads him to dusty press archives in Paris, to the apartment of a sensuous older Senegalese writer, Siga D., living in exile in Amsterdam (and who conserves the only known surviving copy of Elimane’s text), through the narrow streets of Dakar’s bustling medina, and eventually to the small fishing village in the Sine region of Senegal, where Elimane was born.

As Diégane searches for traces of Elimane and reconstructs his travels – through Europe, West Africa, and South America – voices multiply. In this, Sarr’s novel takes its cues from the polyphonic narration of Bolaño’s novel, the vertiginous chronology of Ouologuem’s Bound to Violence, as well as the title of Elimane’s own lost manuscript, Le Labyrinthe de l’inhumain. La plus secrète mémoire des hommes is a serpentine – and, at nearly five hundred pages, tome-like – text, an elaborate mise en abyme. Across the novel’s asynchronous narratives, which span the nineteenth century to the present day, we encounter the various people whose paths intersected with the enigmatic T. C. Elimane – especially the men and women who loved him and lost him, and those he has continued to haunt long after his disappearance.

Diégane’s search for the ghost of Elimane is also ultimately a journey through texts and a patchwork of experimental literary forms. The novel incorporates press clippings, letters, interviews, text messages, journal entries, reports, oral histories, and manuscripts-in-progress. An entire chapter, told from the perspective of Elimane’s aging mother, is narrated without terminal punctuation. In one hallucinatory passage, a glistening pearl of sweat trailing down the body of Diégane’s lover, the intrepid photojournalist Aïda, as the two have sex becomes a visionary microcosm.

Formal virtuosity aside, Sarr’s novel performs an especially adept sleight of hand in its very premise, since Sarr both stages and enacts the ambivalences of navigating the French publishing world as an African writer, satirizing the world of French letters as he soars to its greatest heights. Sarr’s narrator, Diégane, is part of a throng of young, ambitious writers, mostly from the African diaspora, living in Paris and vying for purchase in a cutthroat literary scene, where success comes at the cost of leveraging one’s own identity – whether in terms of race, gender, or sexual orientation – to become legible.

The world of French letters is where Diégane and his friends, like Elimane before them, explore and feed a passion for literature. But it is also a world fundamentally unprepared and unwilling to receive them on their own terms – unable, as Sarr writes, to see the African writer as anything besides a nègre d’exception. ‘In the end,’ Sarr asks, ‘who was Elimane if not the most triumphant and tragic product of colonization?’7 In La plus secrète mémoire des hommes, the French literary scene is at best a dangerous mirage and at worst a death sentence – where the African writer comes to die.

Sarr’s most biting commentary thus is reserved for the French literary marketplace, with its neocolonial and essentialist trappings. The novelist and playwright Marie NDiaye, who in 2009 became the first Black woman to win the Prix Goncourt, is a case in point. Despite being born in France, she was treated as a twenty-first-century évoluée, a term coined by French colonists to describe colonized subjects who had ‘successfully’ assimilated France’s linguistic, cultural, and social norms.8

In Sarr’s novel, the scandal of T. C. Elimane is that he refuses to be viewed within the overdetermined frames of France’s identity politics. La plus secrète mémoire des hommes does not simply ask what happens when an author disappears, but rather what happens when he refuses to be seen.

From its dedication to Ouologuem to its almost forensic allusions to one of France’s most polarizing literary scandals, Sarr’s novel lends itself readily to being read as a mashup of French literary history. Indeed, many of his characters would seem to have rather obvious referents in the world of African letters. Diégane – a young Senegalese writer living in Paris who has already published a novel to some success – can be seen as a double for Sarr himself. Elimane clearly blends aspects of Yambo Ouologuem’s and René Maran’s trajectories. Siga D.’s backstory bears similarities to the biographies of both Ken Bugul, the pen name of the Senegalese novelist Mariètou Mbaye Biléoma, and the Goncourt laureate Marie Ndiaye. Biléoma was born to one of the youngest wives of an old marabout and spent a year in Dakar before earning a scholarship to study in Belgium. Ndiaye is the daughter of a French mother and Senegalese father. She publicly disavowed France the same year her novel Trois femmes puissantes won the Goncourt, and she has since lived in Berlin.

But to tether Sarr’s characters to these apparent historical referents is to miss the point. It is to fall prey to the kinds of essentialist readings and biographical lures that Sarr’s novel both satirizes and deconstructs. In other words, it is to rely on the same reductive frames that gave rise to the tragedy of Elimane in the first place: the tendency to see the African writer not simply as a writer but as what Sarr, in his novel, calls an ideological battleground (champ de bataille idéologique).

In fact, Sarr’s novel is less about an actual literary scandal and more about the scandal of literature itself. It is about how, in the face of immense suffering and rampant inequality, literature continues to offer itself up to us, to borrow Sarr’s own words, as ‘response, as problem, as faith, as shame, as pride, as life.’ It is about how literature inhabits, haunts, and sustains us. It is about why we continue to write and read in the face of great personal risk and in the direst of circumstances. Above all, perhaps, Sarr’s novel affirms that French is an African language. And that the future of literature in French is African.

Notes

1. Barthes’s essay appeared first in English in 1967, in the American journal Aspen, and in French the following year, in the journal Manteia.

2. See Christopher L. Miller, ‘What Is a (French) Author?,’ in Imposters: Literary Hoaxes and Cultural Authenticity (University of Chicago Press, 2018), 45–124.

3. See Christopher Wise, Yambo Ouologuem: Postcolonial Writer, Islamic Militant (Lynne Rienner, 1999).

4. The most likely explanation, Wise suggests, is that Ouologuem told the truth from get-go: that is, his publishers made unauthorized revisions to the manuscript, removing references to borrowings from well-known European sources while leaving those to ‘unknown’ African sources intact. Wise, Yambo Ouologuem, 6–7.

5. Wise, Yambo Ouologuem, 9.

6. The Savage Detectives (Spanish: Los detectives salvajes) is a polyphonic narrative about the search for the Mexican poetess Cesárea Tinajero. In fact, although we learn that Sarr’s character T. C. Elimane takes his alias ‘T. C.’ from the names of his editors at the fictive publishing house Gemini, ‘T. C.’ is likely also a ciphered nod to Cesárea Tinajero’s initials.

7. All translations from French are my own.

8. On this, see Dominic Thomas, ‘The ‘Marie NDiaye Affair’ or the Coming of a Postcolonial Évoluée,’ in Transnational French Studies: Postcolonialism and Littérature-Monde, edited by Alec G. Hargreaves, Charles Forsdick, and David Murphy (Liverpool University Press, 2010).

The Sydney Review of Books and Public Books have partnered to exchange an ongoing series of essays with international concerns. This essay, ‘Putting French Literary History on Trial’ by Doyle Calhoun, was published by Public Books on 6 April 2022.