Just over one year after the Christchurch mosque shooting on 15 March, 2019, the gunman, referred to as ‘Person X’ throughout Jeff Sparrow’s new book Fascists Among Us: Online Hate and the Christchurch Massacre, pleaded guilty in a New Zealand court to 51 charges of murder, 40 charges of attempted murder and another terrorism related charge. His initial plea was not guilty. The change moved proceedings along to the sentencing phase, which has since been delayed by the outbreak of Covid-19.

Outside the courtroom, the violent events that took place in Christchurch continue to reverberate. New Zealand, particularly its Muslim communities, is still deeply affected by the mosque shooting. It has also become a focal point for far right sympathisers in the country. A number of people have been charged for sharing the video of the massacre online (more than thirty by September last year) and reports continue to emerge of threats of violence, inspired by Person X, against minorities.

Across the Tasman, the massacre, perpetrated by an Australian citizen, has had an ongoing impact. In February this year, the Director-General of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) warned that there was a very real threat of political violence by extreme right-wing actors. This was downplayed by some right-wing Liberal Party politicians, such as Senator Concetta Fierravanti-Wells – but a public pronouncement by the head of the country’s domestic intelligence agency suggests that the threat of right-wing terrorism is being taken far more seriously. The following month, a 21-year-old man from the NSW town of Sanctuary Point was arrested for alleged involvement in a right-wing terrorist plot.

Security agencies across the world are making similar statements, with both MI5 in Britain and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service highlighting the growth of right-wing extremism and the possibility of political violence. Australia and New Zealand are the focus of Fascists Among Us but Sparrow is concerned always to link local events to Europe and North America. He puts the Christchurch massacre in the context of a resurgent extreme right across the Western world and asks why right-wing violence has become such a threat.

Sparrow’s book was written and published within nine months of the shootings, and so provides a contemporaneous picture of the extreme right in 2019 in a world where things are rapidly changing. The immediacy of the book means that it is a journalistic investigation of why the shootings occurred – but is also a call to arms for anti-racists and anti-fascists in the face of the threat of right-wing violence, both in Australia and overseas. With the revival of the Black Lives Matter movement across the globe and right-wing concern about ‘antifa’, Sparrow’s book, alongside works like Mark Bray’s Antifa, is a useful guide to the problems that anti-fascists and anti-racists are up against, as well as how they are to be confronted.

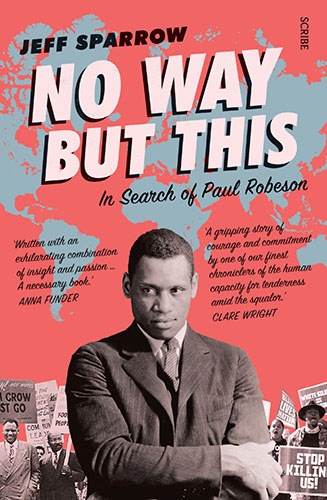

Sparrow has been researching and writing about the far right for years. His previous book Trigger Warnings (2017) looked at the rise of the populist right (and its ‘alt right’ counterpart) across the English-speaking world, charted how the populist right in the United States, Canada, Britain and Australia, had used various culture wars since the 1980s to undermine progressive politics and portray themselves as anti-elitists. As neoliberal economics became consensus for the political centre, the populist right used this anti-elitism to further their agenda and gain power. Donald Trump is perhaps their ultimate success story.

But as the populist right took part in these culture wars against ‘politically correct’ positions on race, gender and sexuality, it opened up space for more extreme elements of the far right to gain traction. Sparrow’s narrative in Trigger Warnings concludes with the 2017 ‘Unite the Right’ demonstrations in Charlottesville in the United States. This brought together elements of the far right from across America, and ended with the tragic murder of an anti-fascist protestor. Trump’s equivocations about extremists existing on ‘both sides’ seemed to show how the far right had been, in the words of Aurelien Mondon and Aaron Winter, mainstreamed. This can be further seen in how the renascent Black Lives Matter movement has been portrayed by the right in the United States, as well as elsewhere across the English-speaking world (including Australia).

The Unite the Right event may have marked the peak of the far right in the United States in terms of organisations. While Trump muddled his position on the alt right, many others, even on the conservative side of politics, sought to distance themselves from the Charlottesville demonstrators. Furthermore, the challenge of anti-fascist activists to the far right grew substantially when they sought to organise in public. Sparrow’s previous book presented the far right at a crossroads: their ideas had slowly entered the mainstream, but as organisations and as activists, they remained on the sidelines. Without anti-fascist resistance, it seemed likely that the far right would further encroach upon civil society and present a clear danger to many minorities.

Fascists Among Us picks up from this point, demonstrating that the far right weren’t able to capitalise on the populist surge as much as they would have liked – and that anti-fascist activism was central to confronting far right groups in public, which dampened their enthusiasm. Sparrow explores how the far right across the Western world responded to this change in conditions and traces the responses to their culmination in far right terrorism, such as the Christchurch massacre in March 2019.

Right-wing terror has previously occurred when both the populist electoral path and the path of mass or street politics has been closed off to the far right, with the more centre right parties siphoning away political support and anti-fascists opposing them in public. Sparrow shows that this has been the case for the far right since 2017. As he writes, ‘fascists could no longer occupy public space, since counter-protests blocked their every attempt’, but after Charlottesville, ‘even the old online activism [was] more difficult, as the big social media companies responded to pressure to police their services’. Terrorism was presented as an alternative option that eschewed the other approaches and the ‘optics war’ that the far right seemed to be trapped in.

Prior to Christchurch in 2019, there had, of course, been other far right terrorist attacks. Sparrow traces a line from Andres Breivik in Norway in 2011 to Dylann Roof in Charleston in 2015 to Robert Bowers (the Tree of Life murderer) in 2018 to the events in Christchurch. Far right political violence, once sporadic, was now accelerating, particularly as other avenues became shut off.

Written firstly for an Antipodean audience, Fascists Among Us interrogates how the kind of far right political violence previously seen in Europe and North America, came to be perpetrated by an Australian in New Zealand. Sparrow identifies the Islamophobic political environment in Australia since 9/11 and its exploitation by the far right as a key driver, as well as a new era of internet radicalisation and right-wing troll culture.

Far right ideas have become mainstreamed over the last decade – and at the same time the far right were able to take advantage of Islamophobia fostered by mainstream media and politicians since 9/11 and the ‘War on Terror’ began. As Sparrow shows, the predominant discourse of the far right in Australia, as well as across the Western world, has been anti-Muslim, seeing Islam as incompatible with ‘Western’ values and society. Islamophobia and the ‘War on Terror’ mutually reinforced each other. Islamophobic discourse helped to fuel the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, to create numerous counter-terrorism laws and to treat Muslims in the Western world as, using Paddy Hillyard’s concept, a ‘suspect community’. At the same time, the ‘War on Terror’ exacerbated Islamophobia, with the populist and extreme right picking up on mainstream Islamophobic discourse and amplifying it. Columnists and TV personalities with millions of readers and viewers, such as The Times’ Melanie Phillips and Fox News’ Bill O’Reilly (and many others, including Alan Jones and Andrew Bolt), spewed forth a hatred of Muslims, tapping into a populist hostility towards multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism. This Islamophobia often took the form of arguing that Islam was incompatible with Western values and that it helped undermine Western society through multiculturalism.

Sparrow also makes clear that contemporary Islamophobia was also driven by biological racism. Exponents argued that birth rates of Muslims were outgrowing white/Western birth rates and that this was a demographic timebomb, which would see Muslims ‘replace’ white populations across the Western world. This racist combination of Malthusianism and Social Darwinism has antecedents in the eugenics movement that came to prominence across the globe from the late nineteenth century through to the 1940s and Nazi concerns about the birth rates of ‘inferior races’. Sparrow shows that these ideas were fundamental to the Christchurch shooter’s politics, with the opening lines of his manifesto repeating, ‘It’s the birthrates’.

This idea that increasing birth rates of Muslims are a threat to the West is manifested through anti-immigrationism, with the far right worried that large non-white populations would eventually seek better lives in the West and subsume white society. This was a central concept in the manifesto of the Christchurch killer, titled ‘The Great Replacement’, which Sparrow connects to French far right circles. A French writer named Renaud Camus wrote a book with this title in 2012, but this in turn owes much to the racist novel by French author Jean Raspail from the 1970s, The Camp of the Saints, which told the story of white Europe being overrun by immigrants from Africa and Asia.

Anxiety about immigrants ‘swamping’ the West has been a constant refrain throughout the twentieth century, with a famous example being Margaret Thatcher acknowledging that people voted for the National Front because ‘people are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture’. As Peter Cochrane has shown in his book Best We Forget: The War for White Australia 1914-1918, white settler-colonial Australia has always feared ‘invasion’ by its Asian neighbours, through military force or by immigration. Sparrow shows that this anxiety of white society being ‘replaced’ has mobilised the far right across the globe, with the slogan ‘You will not replace us’ (or ‘Jews will not replace us’) being the catchcry of the Unite the Right demonstration in Charlottesville.

The ‘great replacement’ theory favoured by the far right is mirrored by the trope of ‘white genocide’, which has been perpetrated for decades, with particular focus on southern Africa. Canadian far right figure Lauren Southern made a documentary in 2018 called Farmlands that alleged that white farmers in South Africa were being attacked en masse by black Africans and suggested that this constituted a threat to the entire white population in southern Africa. This trope has somewhat seeped into mainstream right-wing politics, with both Donald Trump and Peter Dutton raising the plight of white South African farmers.

The proliferation of these far right ideas across the globe has been greatly aided by the internet, which has allowed them to get traction in more mainstream right-wing circles. This is at the heart of Fascists Among Us. Sparrow writes:

the internet allowed activists of the far right to dissolve the distinction between right-wing populism and genuine fascism. The emergence of social media intensified the process, simply by making an equivalent functionality an everyday part of ordinary people’s lives. With the normalisation of Facebook, Twitter and Reddit, fascists no longer needed supporters to seek out exotic destinations like Stormfront [a long-running forum for the far right]: the far right could present its content on platforms that their recruits were already using.

Since the 1990s, there had been concerns about the far right using the internet as a recruitment and propaganda tool, but over the last decade, social media, in the words of Richard Seymour, ‘acquired jackboots’ and thrust far right online culture further than it ever had before. Sparrow shows how trolling became central to far right online culture and the ‘lulz’ shared online fuelled far right actions in real life. And when momentum stalled after Charlottesville, some, such as the Christchurch killer, sought to bridge ‘the gulf between fascism’s online strength and its real-world weakness’. Sparrow spells out how this bridging of the gulf meant ‘terrorist murder’.

While technology has certainly accelerated the far right in recent years, Fascists Amongst Us also highlights that the far right has taken advantage of the angst over climate change and revived the Malthusian concept of overpopulation to argue against immigration and for ethnic cleansing. This, combined with traditional fascist notions of blood and soil, is described as ‘eco-fascism’ and Sparrow shows that this was another key ideological point for the Christchurch shooter.

Eco-fascism has become more prominent in recent years as some on the far right have appropriated the discourse around environmental collapse, although this position competes with the right-wing populist rhetoric of climate change denial. Both of these positions have been on display during the current Covid-19 pandemic, with eco-fascists endorsing the shutting down of borders and heavy policing of non-white communities under the guise of public health, while others on the far right have embraced the conspiracy theory that the Covid-19 is a hoax and called for public gatherings in defiance of public health orders.

Once again, the internet has fostered these far right ideological positions and blurs the line between fascists and populists on the right. Right-wing pundits in the media, such as Andrew Bolt in the Herald Sun or Tucker Carlson on Fox News in the United States, have promoted the idea that China and migrants are to blame for the pandemic and that compulsory public health obligations, such as social distancing and face masks, are threats to personal freedom. In his book, Sparrow details how the far right have exploited many of the problems that we face in modern society to advocate a discriminatory, authoritarian and often violent solution. The pronouncements and actions of the far right over the last few months reveal that the current pandemic has only exacerbated this.

The centrality of social media to the far right has led some to call for the removal of far right activists and trolls from these platforms. After the Christchurch massacre, the New Zealand government pushed for social media companies to take greater steps to limit violent far right content online. These calls have also been made by groups in counter-extremism campaigns. The British anti-fascist organisation Hope Not Hate has been a vocal proponent of this, with HnH’s Joe Mulhall arguing:

The last decade has seen far-right extremists attract audiences unthinkable for most of the postwar period, and the damage has been seen on our streets, in the polls, and in the rising death toll from far-right terrorists. Deplatforming is not straightforward, but it limits the reach of online hate, and social media companies have to do more and do more now.

While many anti-fascists and anti-racists welcome the removal of these people from large social media platforms, others are wary about focusing on this kind of campaign. Sparrow warns in the conclusion to Fascists Among Us that ‘[i]t would be naïve… to expect reforms of the major social media corporations to provide an answer to [atrocities like] Christchurch’. He continues to suggest that ‘a thorough ban on fascist or far-right [social media] accounts seems unlikely’ because:

Even if they can be shamed by political outrage, they’re ultimately driven by the pursuit of profit – and the inflammatory accounts of the far right deliver user engagement that can be monetised via advertising.

A look at the actions by social media companies since the book has been published shows that Twitter has been proactive about removing far right figures from its platform, but Facebook has been much more reluctant. Meanwhile the far right migrate to smaller and more niche social media platforms. This may limit their reach, but the hardcore are still being radicalised.

Sparrow proposes that the way to combat the appeal of the far right, online and in real life, is to offer an alternative. This means openly challenging them, as well as the ‘everyday’ prejudices that swirl around in mainstream political discourse, which fuel and amplify the far right (such as the media platform provided by Australian breakfast television to Pauline Hanson or the right-wing talking points aired by Sky News in the evening). In the concluding pages, Sparrow argues that:

The ideas of the far right remain, after all, deeply unpopular, particularly when they are presented openly. Islamophobia might be widely tolerated, but very few normal people find notions of natural hierarchies and redemptive violence at all appealing, and so the mainstream right remains defensive about any association with fascists.

But in order to open up such rifts, anti-racists need to offer a real alternative, one that extends beyond critiques of the right. They need, more than anything, to offer hope.

Fascists Among Us was written and published in the second half of 2019 – a time when the campaign for action on climate change seemed to be gaining momentum. After the bushfires over the summer of 2019-20, Sparrow’s words struck an optimistic note that political action could be taken to confront both the climate emergency and the far right who fed off the problems facing society.

In the pandemic, this book reminds the reader of a recently passed epoch. But with the reinvigoration of the Black Lives Matter movement across the globe and tensions rising on the streets of America in particular, it is also a warning of the threat that the far right poses – especially as the distinction between the extreme and populist right crumbles. Alongside David Renton’s The New Authoritarians and Aurelien Mondon and Aaron Winter’s Reactionary Democracy, Jeff Sparrow’s Fascists Among Us highlights the symbiosis between the far right and the mainstream right and how this has led to discrimination, authoritarianism and instances of violence. It is a short and punchy intervention and places the Christchurch massacre in historical and political context. Like Sparrow’s previous book, Trigger Warnings, it is provocative and while some may disagree with aspects that Sparrow draws out in the conclusion (such as the debate about deplatforming), it is an engaging read for anybody concerned about the right-wing menace that we face today.

Works Cited

Mark Bray, Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook (Melbourne University Press, 2017)

Peter Cochrane, Best We Forget: The War for White Australia 1914-1918 (Text Publishing, 2018)

Aurelien Mondon & Aaron Winter, Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist Right Became Mainstream (Verso, 2020)

Joe Mulhall, ‘Deplatforming Works: Let’s Get On With It’, Hope Not Hate, 4 October, 2019, www.hopenothate.org.uk/2019/10/04/deplatforming-works-lets-get-on-with-it/

David Renton, The New Authoritarians: Convergences on the Right (Pluto Press, 2019)

Richard Seymour, The Twittering Machine (Indigo Press, 2019).

Jeff Sparrow, Trigger Warnings: Political Correctness and the Rise of the Right (Scribe, 2017)