Our paintings demanded increasing amounts of ‘talking about’ as an integral part of the work. The problem we began to realise was, given conventional expectations, how could we make the spectator accept the importance of the ‘talking about’ part of the work? How could it be made obvious that the conceptual frame work was much more than an invisible support for a physical object?

The Arts Worker

Victoria Perin on Ian Burn, artist against art history

Ian Burn is still best known as a stalwart and apostate of Conceptual art. Reviewing his collected writings, Victoria Perin surveys the less tractable side of Burn’s work, from his speculative studies of landscape to his anecdotal fabrications.

There is a point when Ian Burn quits. It might be midway through his important essay, ‘The Art Market: Affluence and Degradation’, published in Artforum in 1975, where he announces: ‘There are a number of things I can no longer ignore’. Characteristically for this artist, whose heart could hold many arrows, the list of infringements is long and includes the ‘corporate spirit’ of the artworld, the modernist pressure to innovate, the inability for protest art to effect change. Around this time, Australia’s most admired Conceptual artist became our most admirable ex-Conceptual artist. And in giving up on the hopelessly hypocritical artworld, Burn became our best quitter.

One of the most nourishing thinkers in Australian art, Burn is best known for his role in New York’s Conceptual art scene in the late 1960s and early 1970s. To his American peers, after his return to Australia in January 1977, ‘he seemed to disappear’, as the artist Adrian Piper put it. In reality, he had quit his avant-garde art career to work with trade union media. He continued writing, however, and some of his essays from this period have a penitent feeling to them, attempting to stitch back together the pure idea and the beleaguered art object that the procedures of Conceptual art had forced apart. After a period of giving up (or pretending to give up) artmaking, he returned with a flourish of late works, a few short years before his tragic drowning in 1993.

You can be excused if you have the impression that Burn’s fundamental importance is being ‘the only Australian ever to be central to an internationally significant art movement’ (as curator John Stringer claimed in one of the most inadvertently provincial artist’s bios ever written). The new publication Ian Burn: Collected Writings 1966-1993, edited by Ann Stephen, certainly does not dislodge that opinion. But if that is our shallow view of the artist, Collected Writings goes much deeper, providing a more sincere portrait of this sincere artist.

Burn, the author, is not virtuosic — his voice lectures rather than sings. One apt description of his prose highlights its ‘kind of awkward internal complexity’. Despite this, as Stephen admits in her introduction, this is now the third publication devoted to Burn’s writings. It’s unusual in Australia, where there are only a handful of books collecting the writing of artists. This new book is an invaluable addition, superseding Dialogue: Writings in Art History (1991), a selection made by Burn himself, and being more expansive than Ian Burn: Art: Critical, Political (1996), a volume devoted to his work in the Australian labour movement, edited by Sandy Kirby. Stephen has rejected a few texts included in those earlier publications, but she has added more that were previously hard to find. Other features include a selection of constructive memorial lectures given by Burn’s Conceptual art peers, Piper and Mel Ramsden, photographer and theorist Allan Sekula and art historian Paul Wood, a complete listing of Burn’s published writing, along with brief annotations introducing each selected text. Overall, there are almost fifty texts by Burn and co-writers, including powerful essays such as the forementioned ‘The Art Market: Affluence and Degradation’ (1975), as well as ‘Why do they keep on coming?’ (1977), ‘The 1960s: Crisis and Aftermath’ (1981), ‘Is art history any use to artists?’ (1985), ‘The Re-appropriation of Influence’ (1988) and more.

Stephen’s thorough introduction is also enlightening, both as a guide to the twists and turns of Burn’s biography, as well as an introduction to the growing field of ‘Burn studies’, comprising some arid scholastic tussles over the artist’s legacy (more on this to come). Stephen, who was Burn’s friend and collaborator in his later years, has long directed the discussion on his art. Her sustained monographic research may be unmatched in Australian art. After authoring Burn’s biography in 2006 and curating all of the major exhibitions that have contextualised his works since his death, Stephen has produced what feels like a final, definitive statement outlining her vision of the artist’s contribution.

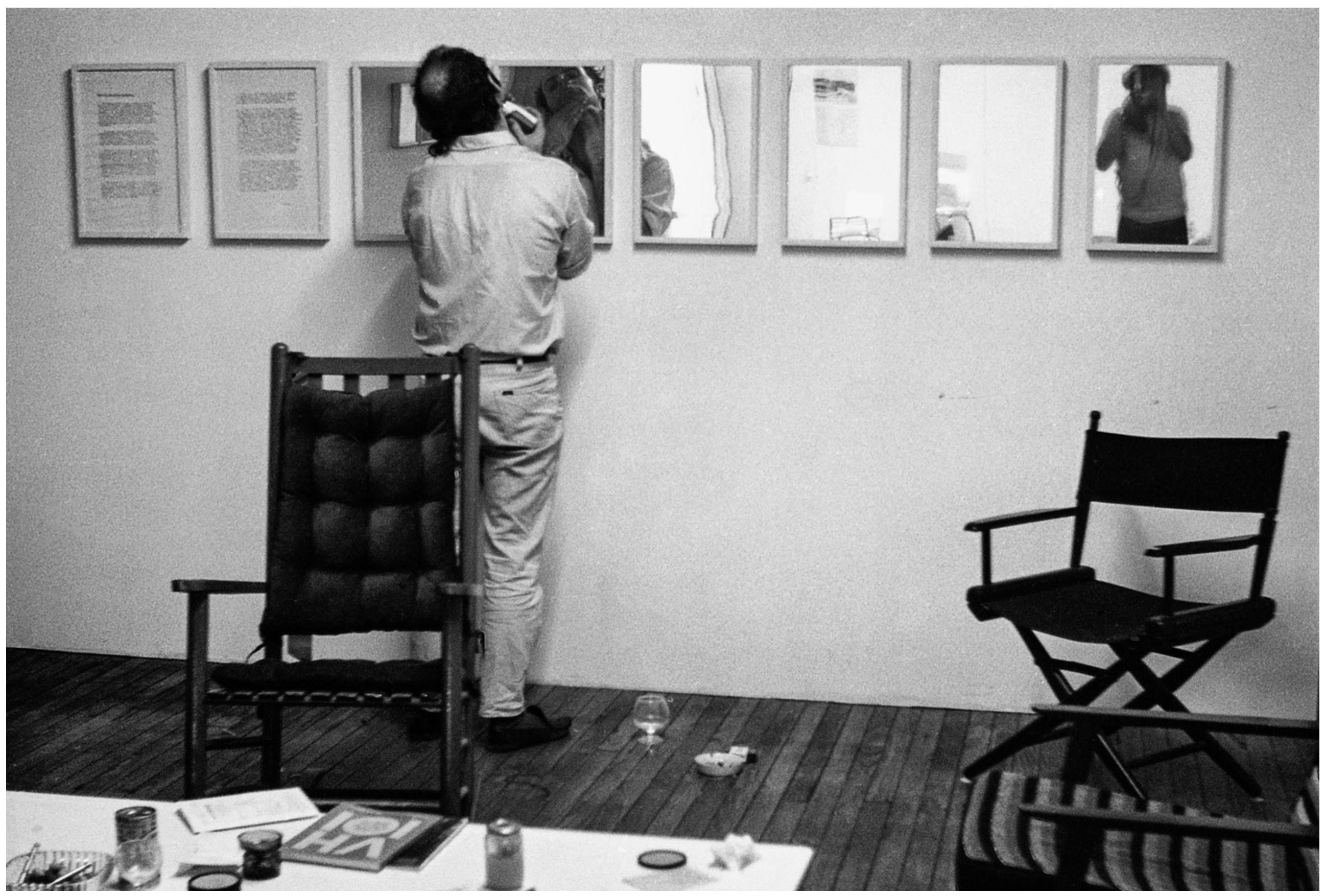

Ian Burn shaving in Mirror Piece (1967), photographed by Mel Ramsden, 1967. Courtesy the Estate of Ian Burn and Milani Gallery, Meanjin/Brisbane. © Estate of Ian Burn and Mel Ramsden.

Split into two sections – before and after his return home – the structure of Collected Writings reflects the trajectory of Burn’s relationship to Conceptual art, which he quit only after being a key advocate of its necessity. Moving to London in 1964 and New York in late 1967, he joined a noisy cohort who began to believe that:

Subsequently they put the ‘talking about’ part of art ‘directly up on the wall’ — so that these communicative observations ‘became a feature of the “style” of Conceptual Art’. He helped form the New York branch of the British art collective Art & Language, which had been established in Coventry in 1966. In Art & Language’s version of Conceptual art, artworks could appear as dense paragraphs of text, diagrams, talk, crosstalk, actions, filing cabinets, essays, meeting minutes, or general busywork that they termed ‘proceedings’. When art was divested of image, object, and performance, the only material left standing was the word.

In the early 1970s, when Burn was deep in the weeds of the Conceptual art movement, his writing was directed to a very small audience of peers. Reading this era of Burn feels like intruding, as you realise his ‘we’ is not you, and many of the imperatives insisted upon have long since been surrendered. ‘Up to now we have been concerned with selecting what kind of building materials we need,’ begins an article directed at his Art & Language colleagues. ‘Now that the materials are available and are lying around loose, we’ve got to figure out how to put them together.’ Here Burn and his co-author Mel Ramsden are not writing about bricks and mortar, but rather articles in a journal that none of their peers could quite synthesise:

That there are different kinds of connections between a number of the articles is not as plain as it could be. There is little point in testing the ‘timber’ of the arguments unless one can move to testing the way they will be joined to other pieces of timber — and that is not just a matter of where it joins and what kind of joint is appropriate, but it is also importantly a matter of understanding the role each piece of timber plays in relation to all the other pieces of timber and whatever the use is to which the construction is to be put. Nor is it just what one is obviously building, it is also where and how this fits together with other buildings and into the over-all geography of the landscape.

With members positioning, repositioning, opposing, and pivoting around each other, the intellectual ambition of the Art & Language was matched by fiercely self-referential writing. They were building a house (an art collective) that would help them see far over the landscape (the artworld, and beyond), if only they could stop disagreeing with each other (they couldn’t). Deflated by the struggles of collective artmaking and disturbed by the ‘pathological isolation’ of the New York art scene, Burn left the influential Art & Language project and New York.

There are two unorthodox aspects to the texts that Stephen has chosen. The first is the inclusion of text-based artworks as ‘writing’, a strategy that Piper also uses in her ‘collected writings of “meta-art”’. The earliest texts here come in the form of instructions, wall-labels, spoken scripts, and annotations for conversations. Stephen’s decision to include artwork texts immediately establishes that Burn’s writing was honed as a function of making a particularly esoteric brand of art. This odd apprenticeship colours his entire written output. Throughout his career, Burn was attuned to the differences between artists’ writing and the writing of non-artmaking academics and critics. Burn’s healthy distrust of those without skin in the game was a product of his peer-led training.

The second, more unusual aspect of this collection of writing by a single author, is the inclusion of so many co-authored texts. Burn was a serial collaborator, and over a third of the selection is co-written, with many others credited to productive conversations with colleagues. Soft-Tape (1966), the first ‘text’ in the collection, is an artwork by Burn and Ramsden – his first great collaborator, who passed away only recently in July 2024 – in which a tape of someone speaking is played at a near imperceptible volume. In Collected Writings, Soft-Tape is reproduced as an assembly: a diagram, an installation image, a wall-text, a transcribed script, and a retrospective reflection about the work penned in 1990. We don’t get far into the transcription before we are told that it was written by Ramsden. Immediately, Stephen invites us to dip our toe into a deep channel of anti-individualism that challenges any sense of Burn as an exceptional or singular author. To ask why this book shouldn’t be called the Collected Writing of Ian Burn and Co., is to ask a Burnian question.

Until his last years, and perhaps not even then, Burn never truly wrote alone. In early 1967, he was living in London and struggling to write an essay for Art & Australia, the most important art journal active back in his home country. In February 1967, he detailed his process in a letter to the Naarm/Melbourne-based artist Paul Partos:

I got both you and Mel [Ramsden] to go through it for me. from both your comments I reworked and rewrote it making a third draft. That didn’t read as well […] so I made another draft of it, which I have just finished. So this weekend Mel and another guy are going through to see how it reads […] the trouble is Mel is so involved in it himself now that he can’t read it clearly, so I have got someone else who knows nothing about it at all to go through it also.

In April, after his final draft was rejected by Art & Australia for being convoluted, Burn bristled: ‘I can’t agree with any of their comp[l]aints. The few people that have read it have commented on the clarity of the writing, in fact one comment was that I had made it unnecessarily simple.’ The participants in this transnational echo chamber would change over the years, but Burn’s reliance on feedback loops would never waver. The source of the ‘awkward complexity’ in Burn’s writing might be this peer-review process, which gave each text an elaborate, ensemble-led origin story.

This collection begins with Burn at the age of twenty-six. Stephen’s 2006 biography introduces the artist as a networker – adept at socialising with his own generation, as well as with older, art establishment figures, such as his mentor Fred Williams, the Head of the National Gallery School John Brack, gallerist patron John Reed, and the canny young art teacher James Mollison (later the Director of the National Gallery of Australia and the National Gallery of Victoria). Young Burn was a good talker, but in New York he learnt how to write. Collected Writings lays bare this painful process, as Burn and Ramsden descend into very bad writing, before emerging with the scars that testify to their struggle.

After beginning in London, Stephen’s selection sets us off chronologically, following Burn’s move to New York in late 1967, where Soft-Tape is followed by other works of Conceptual art and Conceptual art commentary, such as the text accompanying Burn’s celebrated work with glass and mirrors. Collected Writings tracks Burn and Ramsden’s wholehearted embrace of analytic philosophy and quick enmeshment with their new British colleagues. As Stephen writes, this cohort was reading and raiding ‘various academic disciplines in the history and philosophy of science, anthropology and analytical philosophy’, and this reading was being regurgitated as a style as much as it was being used to explore systems of knowledge. They took stands: against the Duchampian readymade, against the pompous individualism of modernism, against those who reductively described Conceptual art as de-materialisation. Yet, until about 1972, all of this opposition was delivered with the unhurried pace of turkeys scratching around the leaf-litter:

Then when I am confronted with an object which has every appearance of being a painting (so that it does not occur to me to question it) how plausible is raising the questions: ‘Is this a painting?’ or ‘Is this not a painting?’ (the logical forms of which stand ‘Is the sentence “this is a painting” true?’ etc.).

If he never quite grasped the value of urgency, Burn would eventually relinquish the tedious grammar of recursive questioning.

Sometimes accused of ‘bad or amateur philosophy’, Art & Language’s reception has always been mixed. In 1971, a selection of Burn and Ramsden’s texts was sent to Australia to be included in an exhibition at Pinacotheca in Richmond. The local art audience, who had previously been extremely curious about the work of their expatriate peers, turned cold on the esoteric direction their writing had taken. As Ramsden retrospectively concluded: ‘They thought we were just getting too pretentious and smartarsed and that we were not fooling them and that we needed taking down a peg or two. They were right. This wasn’t proper philosophy and it wasn’t proper art.’

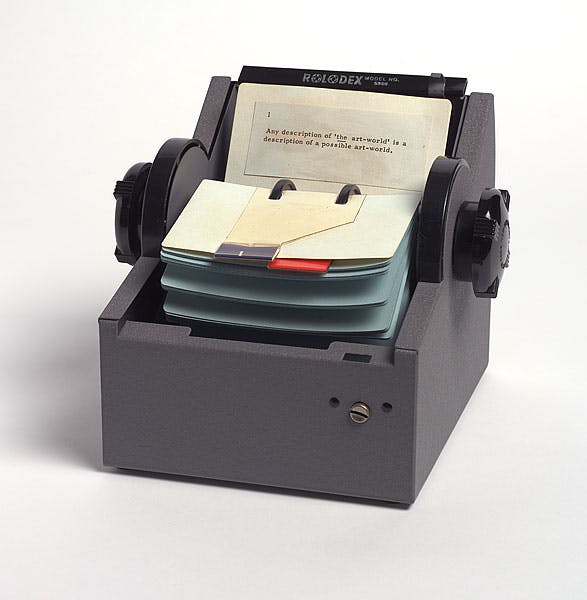

Impressively, the Art & Language collective surmounted such criticism with ‘Blurting’, the most successful written form developed by the group. Comprising brief statements and annotations, blurts were a written approximation of conversations that Art & Language exponents in New York were having in Burn and Ramsden’s lofts. On a weekly basis from January to July in 1973, eight participants each received ‘about ten different annotations (one or two from each of us)’, to which they could respond. In a process ‘analogous to librarianship’, the blurts were then de-authored, de-chronologised, and ordered into categories with notation that encouraged a non-linear flow. Blurting hurdled the limits of Burn’s earlier analytic writing, characterised by its autodidactic wordiness, to showcase the lean conceptual scaffold surrounding Art & Language’s core dilemmas.

Ian Burn & Mel Ramsden, Index (model…), 1970, typed statements collaged on 12 file cards in metal rotary card file, 23 x 23 x 21.8 cm (object). Collection: National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra. Courtesy the Estate of Ian Burn and the NGA. © Estate of Ian Burn and Mel Ramsden.

One blurt about blurting reads, ‘Blurting is a way of catching as much of our conversations as we can: maximising our conversational exchanges’. It was seen as an efficient, time-saving device: ‘An optimal speaker-hearer context would involve immediate recognition of each individual's presuppositions. Under those ideal circumstances blurting would be more expedient than time consuming academic arguments.’ But blurting is nothing if not a procedure in self-scepticism; ‘How are our proceedings going to function in the art-community?’, they asked themselves. ‘The language that we use is not the ordinary language of the art-community. Why is this so? . . . [The art-community’s] vocabulary is as specialized as any other. In terms of translation there might not even be an equivalent for our meanings in their language. This is what is sometimes referred to as the “indeterminacy of translation”’. Blurting was thus both a continuation of and a response to the limits of their highly insular communications.

Blurting does not appear in Collected Writings. Stephen notes apologetically that it would be ‘impossible to extract’ Burn’s contribution to the blurting project, despite its being ‘a major activity in which Burn actively participated’. While this is undoubtedly true, without the blurts, Collected Writings loses a foundational element in Burn’s style; much of his later writing has the tumbling rhythm of tangential blurts. At the same time, we also miss a sense of how Burn worked through his relationship to audience. Once the hermetic Art & Language imploded and he returned to Australia at the age of thirty-seven, one of the things he ‘could no longer ignore’ was the futility of treating your immediate peer-group as your ultimate audience. As Ramsden has retrospectively suggested, an audience made up of your friends, or people ‘who you could see today’, is akin to having no actual audience at all.

In the second half of Collected Writings, covering the years 1980-1993, the inexorable inching of the New York years, full of hesitation and doubling-down, is replaced with a sprint. During this period, Burn is writing through several remarkable inquiries simultaneously, in a variety of stylistic gambits. Stephen has thoughtfully organised these years into four themes: Burn’s fascinating writings about art and workers’ unions, his contestation of the history of Australian landscape art, a series of critical reflections on the avant-garde of the 1960s and 70s, and finally, a handful of texts revolving around an idiosyncratic motif Burn nurtured from at least 1968, consisting of a distinction between reading, seeing and looking. Burn pitched each concern to a different audience that rotated between art students, gallery visitors, blue-collar workers, white-collar workers, the academy, old and new friends, as well as old and new foes.

As Camille Orel’s review of Collected Writings demonstrates, Burn is arguably the most influential local art theorist for the generation of art historians emerging in Australia today. Stephen’s authoritative selection of Burn’s early art-writing and the retrospective lectures that close the volume frames the Conceptual art movement (and its dismantling) as Burn’s most widely admired project. While Stephen’s introduction largely skirts his union work and his art historical revision of settler Australian landscapes, it is these two sections that appear to excite younger academics most.

Despite Stephen’s tireless research, art historian and gallerist David Homewood has somewhat pointedly identified ‘gaps in knowledge’ about Burn, including his ‘under-theorised’ labour activism and all the work he made before leaving for London in 1964, such as the juvenilia of ‘the teenaged landscapes and still lifes from 1950s’. Some efforts, such as Nicholas Tammens’ research project Ian Burn et al., are deliberately carving out niches around Stephen’s scholarship, by highlighting his union work. Given the implied charge that she has neglected aspects of his practice, I do wonder how much we are expecting one scholar to address. Readers interested in Burn’s activism can seek out the recollections of Burn’s later collaborators, such as the artist Ian Milliss, and will still find Sandy Kirby’s Art: Critical, Political (1996) invaluable.

Burn’s Australian art history is another story – so unusual that it has received very little analysis. Stephen settles on a fashionable description of it as ‘anti-colonial’, while the truth is much harder to parse. National Life and Landscapes: Australian Painting, 1900-1940 (1990) – Burn’s only solo-authored, book-length publication – is represented in Collected Writings by excerpts from its introduction and conclusion. In the book, Burn argued against the alignment of progressive and conservative art with progressive and conservative politics, an anti-avant gardist logic that he hitched onto a reassessment of unfashionable landscape painting between Federation and the Second World War. Burn believed that we had lost a ‘broad historical understanding’ of early twentieth-century Australia due to an academic obsession with progressive chronological ‘isms’ that claimed to ‘represent the authentic modern vision of the world’. But art, he maintained, never runs in a straight line. The true impact of the modern era could be found in landscape art hitherto condemned as the soapy, regional ‘gumtree school’.

Could it be that the provincial conversative painters revealed more about Australian society in this period than the cosmopolitan modernists? Supported by experimental visual analysis, Burn determined, for instance, that the privileged symbolism of ‘the parched landscapes of Gallipoli’ lent ‘its significance to pictures of the parched inland of Australia’. In the ANZAC mythos of nationhood was a topographic rhyme between the Middle East and the outback; nationalistic visions of Australian at war in Turkey and Palestine were transposed into a new fetishisation for deserts and tough country.

Burn’s arguments about settler positionality should be read alongside the significant essays on Albert Namatjira that he co-wrote with Stephen – essays that utilise the same speculative visual analysis that would become Burn’s signature. With a steadfast belief in the knowledge that could be gained from simply looking at art (specifically paintings), National Life and Landscapes ultimately represents a-painter-led theory, and as such, his ideas are as unpopular with academics as other locally developed art theories, such as Max Meldrum’s tonalism or Jindyworobakism. Burn contests Bernard Smith’s account of the same era in Place, Taste, Tradition (1945), which has been described as the world’s first Marxist art history. But alongside Smith’s book, National Life and Landscapes remains one of Australia’s most ambitious materialist art histories.

With the publication of Collected Writings, it now seems imperative to shift the focus away from Burn’s contribution to the Conceptual art movement towards these less celebrated artistic and historical interventions. This is not least because Burn’s writing shows him repeatedly downplaying the exceptionalism of his early career. Even Burn’s most iconic action, renouncing Conceptual art, was part of a ‘mass defection’ he saw enacted by ‘many artists who moved through Conceptual Art to more direct engagements with “real-world” issues’. More profoundly, Burn saw the art historian’s reductive tendencies as plainly self-serving. Art historians, he observed, often neglected the historical aspect of their discipline; ‘they have appeared more interested’ he complained, ‘in imposing their own understanding and staking out “property” claims’ over artists’ work.

Privately, Burn would disapprove of colleagues, who, as tall poppies, asserted their significance as either artists or historians. Stephen is not immune from continuing Burn’s wars against old combatants, finding it necessary to recount Burn’s falling-out with Terry Smith, a fellow-expatriate member of Art & Language. Stephen takes pains to explain how Smith’s seminal article ‘The Provincialism Problem’ (1974) was simply a codification of Burn’s account of the unequal relationship between central and peripheral locations in art. While Smith’s text became canonical, Stephen draws attention to Burn’s own depiction of late modernism as a game with a covert ‘trick ensuring all artists play by the American rules, while only Americans can win’. Stephen again emphasises that ‘Burn ghost-curated the first museum survey’ on Conceptual Art and Conceptual Aspects with fellow artist, Joesph Kosuth, probably because Kosuth has previously minimised Burn’s contribution and centred his own. Still, I wonder if taking up Burn’s factional squabbles is the best way to perpetuate his legacy.

Stephen also raises more unexpected grievances against ‘some art historians’ who have ‘co-opted’ Burn’s concept of ‘peripheral vision’ and flattened its ‘precarious and risky meaning’ into a ‘postmodern position or postcolonial space’. This objection is strange, as Burn certainly did use ‘peripheral vision’ to describe a challenge to Western vision, and a perspective that ‘“cuts across” cultures, producing moments of (seeming) clarity when conflicting cultural traditions see eye-to-eye without appearing to look at each other’. But the reason for Stephen’s objection becomes clear when she introduces her own Freudian interpretation of the term, quoting psychoanalyst Adam Phillips’ description of a ‘“wide or free-floating attention” that allows for receptivity, a mode of listening or looking that “doesn’t know beforehand what is of interest”’. To me, Burn appears too restlessly critical to embody this floating, impartial eye. In any case, this jostling of over-reaching interpretations is very Burnian, even if the gatekeeping of his terminology is not.

Burn once brooded that ‘artists survive beyond their art through art history, so histories still have to be written as if they mattered, a matter of life and death’. But what’s a Burn scholar to do? When your subject hates your discipline and disdains its practitioners, what avenues do you have to continue to study them? ‘Is Art History Any Use to Artists?’, easily one of Burn’s landmark essays, vibrates with the problem of being an artist who writes. Artists, he contends, have their own version of art history, derived from an oral tradition of ‘stories shrewdly selected and edited to make the most telling points’. He was describing not facts, but anecdotes. With the power to connect the speaker to an historical lineage, ‘an anecdote creates its own necessity,’ Burn quipped, ‘truth notwithstanding’. Burn’s advice to art historians? You’ve got to think, look, and listen like an artist.

His late achievements are devoted to the anecdote. For this, three moments revolving around French Cubist Fernand Léger stand out, and despite Stephen’s characterisation of Burn in his biography as ‘no hoaxer’, I call them Burn’s hoax texts. In ‘Is Art History Any Use to Artists?’, Burn plants his first faux anecdote when he tells a ‘little-known story about the time Fernand Léger briefly visited Australia in 1956’. Driving in the outback, Léger could not ‘understand’ the Australian landscape – that is until he was ‘shown several collections of Australian art […] In particular, some 1940s Wimmera landscapes by Sidney Nolan’. Burn was not simply writing Borgesian fiction here (Léger died in 1955), but by inserting an ahistorical moment into a non-fiction essay, he was writing a statement that would ‘account for the “Australianness” of bits of Léger and other artists’. How to account for visual evidence that doesn’t conform to historical fact? One solution was to lie.

Another lie:

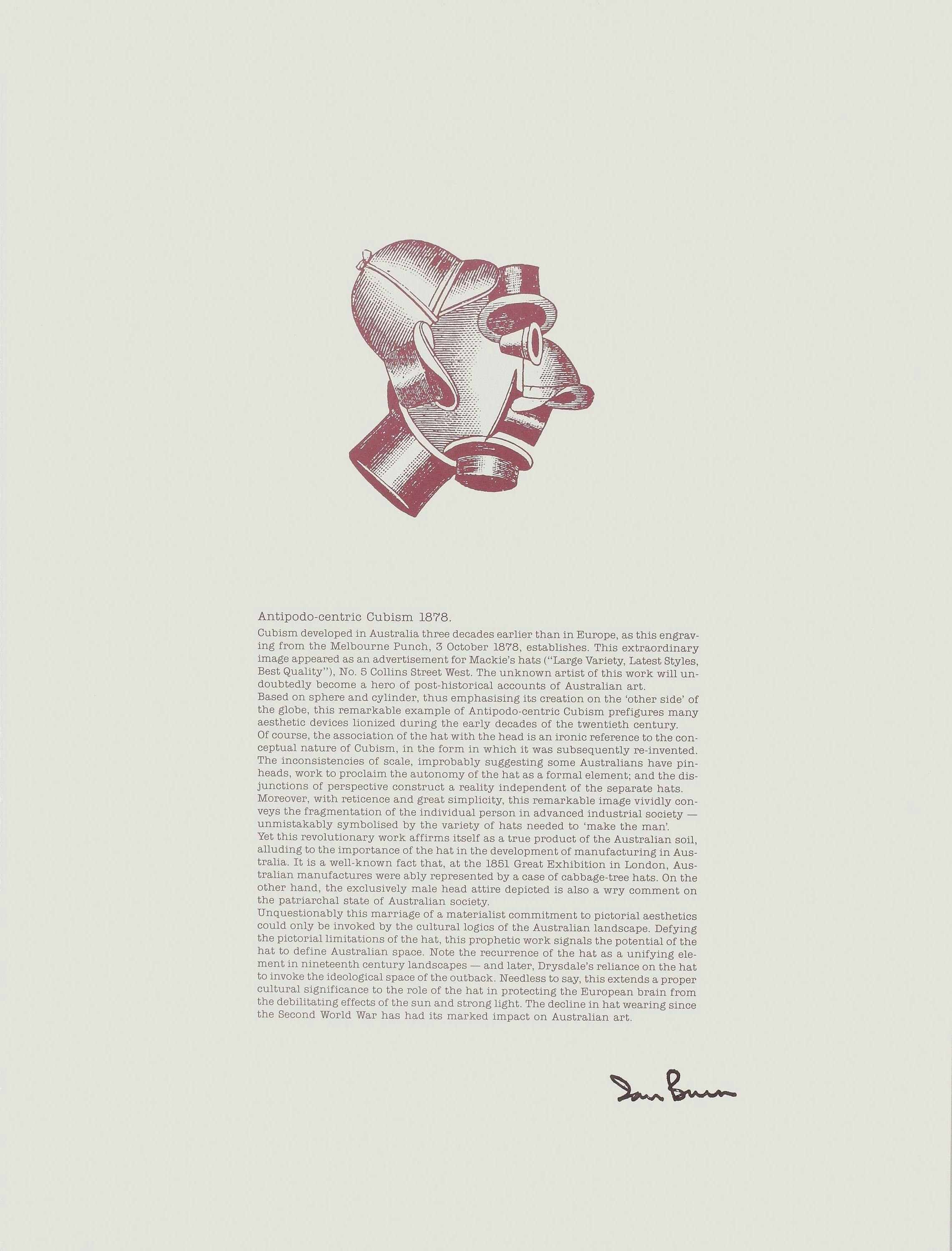

Cubism developed in Australia three decades earlier than in Europe, as this engraving from the Melbourne Punch, 3 October 1878, establishes. This extraordinary image appeared as an advertisement for Mackie’s hats (‘Large Varity, Latest Styles, Best Quality’), No. 5 Collins Street West. The unknown artist of this work will undoubtedly become a hero of post-historical accounts of Australian art.

This text is from Antipodo-centric Cubism, 1878, an artwork from 1986. It’s only a prank if you think he’s joking. But under what conditions is Burn wrong? An anecdote: when I was researching Burn years ago, I found that no online archive of Melbourne Punch had 3 October 1878 fully digitised. Elbow deep in microfiche, trying to fact-check this hoax, I realised I was the very figure Burn despised: the pedantic academician. The insignificance of my quest was powerful testament to Burn’s dislike of the historian’s project: hunting for petty victories, relishing minor triumphs over modest contentions.

Ian Burn, Antipodo-centric Cubism, 1878, 1985 offset lithograph, printed in colour ink, from one plate, edition of 40, 56 x 42.1 cm (sheet). Courtesy the Estate of Ian Burn and Milani Gallery, Meanjin/Brisbane. © Estate of Ian Burn.

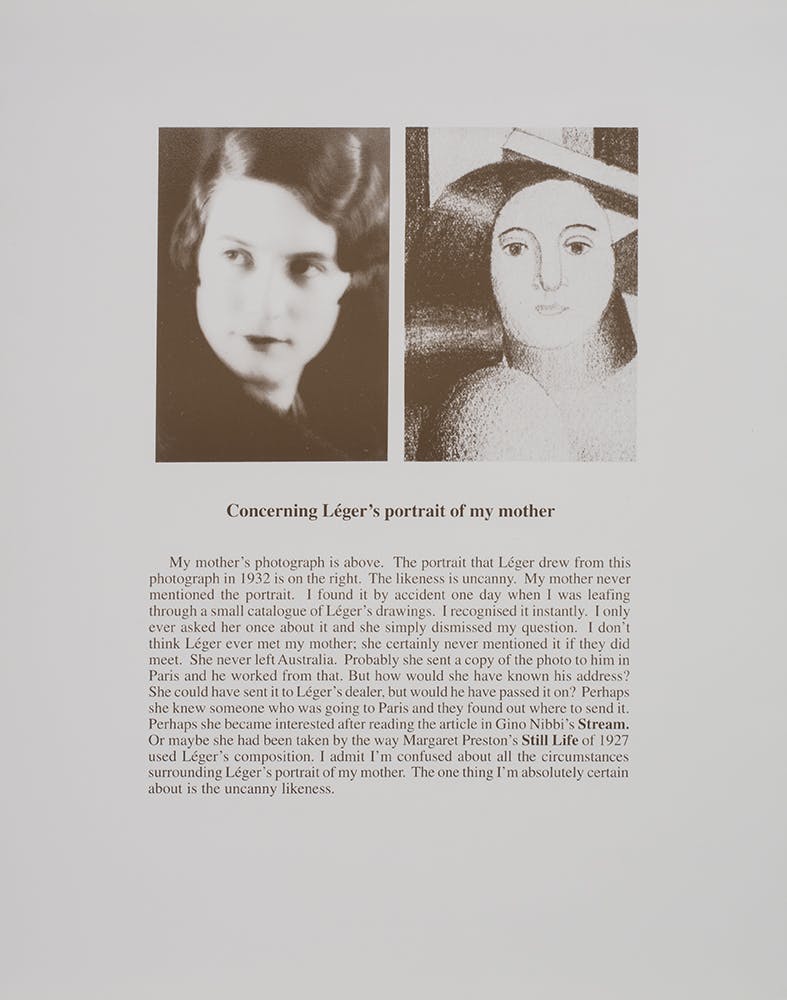

Another hoax is smuggled into the print, Concerning Léger's portrait of my mother (1990), in which Burn asks how Léger could have drawn a portrait of his mother when ‘she never left Australia’? Burn finds the portrait in ‘a small catalogue of Léger’s drawings’ and recognises his mother ‘instantly’:

I don’t think Léger ever met my mother, she certainly never mentioned it if they did meet. She never left Australia. Probably she sent a copy of the photo to him in Paris and he worked from that. But how would she have known his address? She could have sent it to Léger’s dealer, but would he have passed it on?

The novelist Gerald Murnane writes in this sort of delusional logic, a persistent indulgence that wears the reader down so that we surrender to his eremitic perspective. In contrast to Murnane’s vast mental landscape, Burn’s ploy is a brief paragraph – not a poem nor a full monologue. Still, the text contains a whole rhetoric about influence and historical record meeting a man’s personal vision, as he gazes at his mother’s face. What he sees is irrefutable. Burn admits, ‘I’m confused about all the circumstances surrounding Léger’s portrait of my mother’, but he is not confused about the likeness. We waver under his conviction. I’ve always found this last hoax one of Burn’s most compelling pieces of writing. Surprisingly, neither Antipodo-centric Cubism, 1878 nor Concerning Léger's portrait of my mother – artworks initially created for union-fundraising – is included in Collected Writings. Why not, especially when his early Conceptual texts are? Young artists (not to mention academics) could take license from these succinct late works that challenge the primacy of historical fact over feeling, intuition and observation.

Ian Burn, Concerning Léger’s portrait of my mother, 1990, offset lithograph, printed in colour ink, from one plate, edition: undesignated, 50.5 x 40 cm (sheet). Collection University of Queensland. Courtesy the Estate of Ian Burn and the UQ. Photo: Carl Warner. © Estate of Ian Burn

If there is one thing you can say about Burn, he was not a hypocrite. When his convictions were challenged, he examined them, responded, or wrote an essay explaining how he changed his mind. Yet in her lecture ‘Ian Burn’s Conceptualism’ (1996), Piper takes pains to stress ‘consistency’ as his key distinguishing feature, whereas Charles Green notes that Burn ‘doesn’t seem to have ever left anything completely behind’. He might have changed how he wrote, where he wrote, what he wrote about, and whom he wrote for, but through the choral performance that is Burn’s Collected Writings, a clear portrait of the artist emerges: a figure defined by dogged persistence and a frankly unfashionable integrity.

Hiking through the 775 pages of Collected Writings, you will find yourself understanding Geoffrey Batchen’s characterisation of Burn as ‘an earnest and thoughtful teacher’, even if he was ‘without much entertainment’. If this sounds like criticism, it is not intended to be. Collected Writings is not a display of Burn’s genius, it is a record of his work. If he is occasionally awkward or overly complex, the solidity of his convictions and the intensity of his labour offer more than adequate compensation. How apt that Burn’s writing acts out this final honesty?