The opportunity to write music for an exhibition of paintings by Turner was irresistible. Turner had been a favourite artist since I was a teenager; I vividly remember the thrill of seeing Rain, Steam and Speed for the first time. I wasn’t interested in composing an impressionistic response to the paintings; I wanted to know more about the complex personality of this great artist. My efforts to understand Turner better led me to his mysterious poetic work The Fallacies of Hope.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) was born on Maiden Lane in Covent Garden, in the heart of working-class London. The son of a barber, he kept his Cockney accent and his disdain of luxury throughout his life, although by his mid-twenties his paintings were being avidly collected by aristocratic patrons and he was never to want for money again. He may have disdained the things that money could buy, but money was certainly important to him, perhaps because of his humble and financially precarious beginnings. His mind was ‘ever painfully exact in money matters’ according to his first biographer, Walter Thornbury; he was impelled by a ‘spirit of greedy acquisitiveness to amass money’.

In view of his material success, one might imagine that Turner would share in the hopeful ideology of the industrial age – the belief that a better world was being built, and that anyone with talent and determination could rise in position and wealth, as he had done. Progress was the new god and hope for a better future was the gospel it spread – or the drug it peddled. Turner was the first great painter of the modern industrialised world, which he saw in all its magnificent, terrifying power, rushing headlong towards us through the storm of societal upheaval, like the train in Rain, Stream and Speed. Turner’s attitude to the emerging brave new world was ambivalent at best; he seems to have regarded hope as a delusion, a fantasy, a distraction from the harsh realities of the world. But to attribute this to pessimism alone is too simple: nothing about Turner is simple. He had reason to be bitter; his later works were frequently met with derision or incomprehension. Critics sought to outdo one another in heaping vituperation on paintings that were ‘dismissed as absurdities’, ‘scrapings of the palette’, ‘extravagances all sensible people must condemn.’

For decades Turner let it be known that he was writing a long poem entitled The Fallacies of Hope. This phrase became so closely associated with Turner that a widely circulated and by no means flattering lithograph portrait of Turner bore the inscription ‘The Fallacy of Hope’ – implying that Turner himself was its living embodiment. Turner’s obsession was even satirised in the humorous journal Punch. Mystery surrounds the poem: Turner deliberately, perhaps mischievously, encouraged the mystery. Some of his paintings were exhibited with what he described as lines from the poem, beginning with Snowstorm – Hannibal and his Army crossing the Alps (1812). But the poem was never published. Turner bequeathed his remaining works to the nation, a magnificent legacy now held by the Tate Britain, but after his death in 1851 no manuscript of the poem was found. Did it in fact exist, or was it a long-running bluff by the artist?

There are hundreds of lines of poetry in Turner’s papers; lines allegedly belonging to The Fallacies of Hope are a tiny fraction of the total. Turner took his poetry seriously, though most of his contemporaries did not. Thornbury calls him ‘the dumb man making noises, and fancying himself an eloquent speaker’. The best he can say is that ‘Turner felt poetry and painted poetry, but he could not write it’. The Art Union worried that Turner’s ‘wretched verses may have had some deleterious influence on the painter’s mind’.

Turner was not the first poet to question the reality of hope; in Shelley’s The Masque of Anarchy (which Turner may have known) Hope is ‘a maniac maid’ who ‘looked more like Despair.’ Morning, Returning from the Ball, St. Martino is one of several Venetian paintingsthat Turner exhibited in 1845 with the note ‘MS. Fallacies of Hope’, but no accompanying verse. (It was this painting which elicited the parody of Turner’s poetry in Punch.) Just a single line accompanies Visit to the Tomb (The Times indignantly asked, ‘What tomb?’) Exhibited in 1859, it depicts an episode from the story of Dido and Aeneas, with the line: ‘The sun went down in wrath at such deceit.’

The sun features prominently in Turner’s verse, as it does in his paintings. According to Ruskin, Turner said ‘The Sun is God’ – a few weeks before ‘he died with the setting sun on his face.’ In the verse accompanying Snowstorm – Hannibal and his Army crossing the Alps, Hannibal ‘look’d on the sun with hope’ – a cruelly deceitful hope of course. In War. The Exile and the Rock Limpet (1842) Napoleon, with the setting sun behind him, ‘stands alone amidst a sea of blood’. Ruskin commented that ‘the lines which Turner gave with this picture are very important, being the only verbal expression of that association in his mind of sunset colour with blood…’

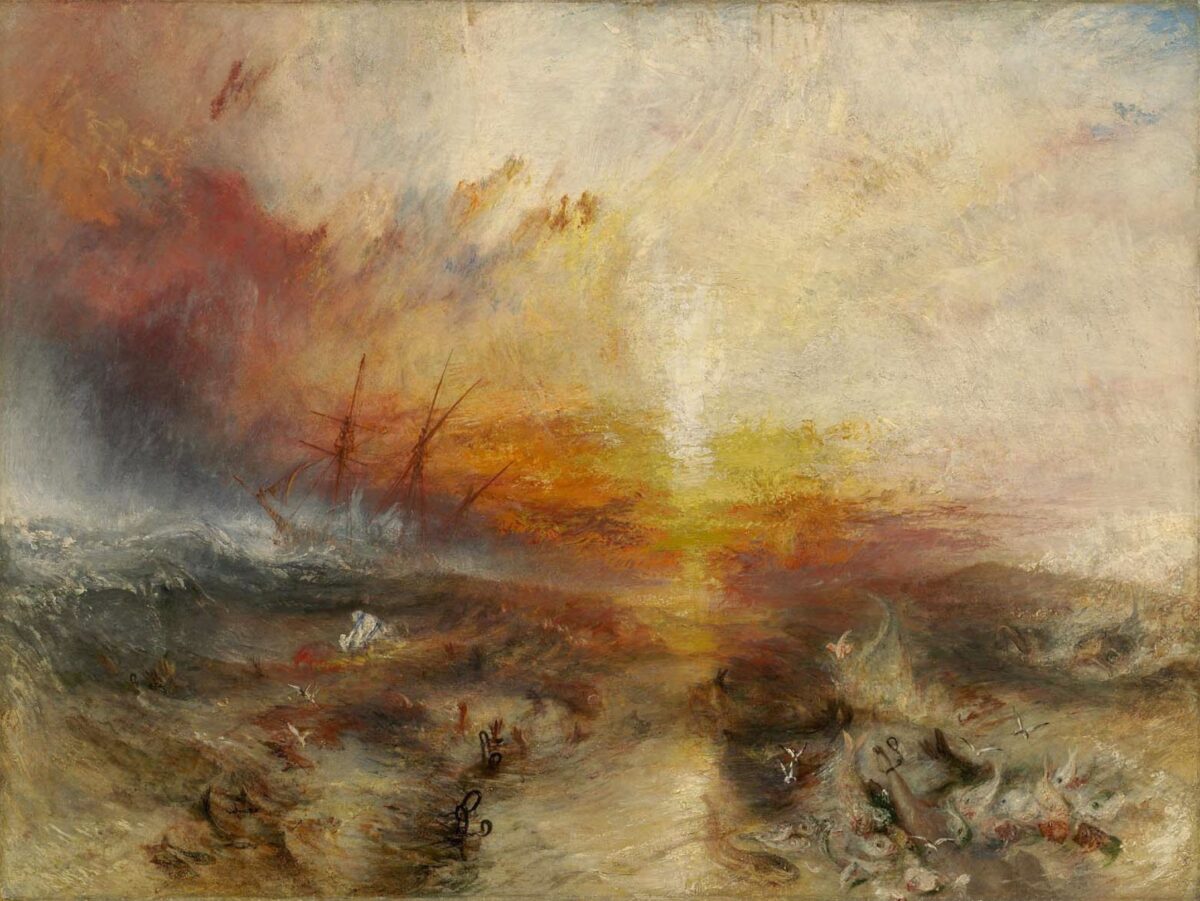

The most famous painting to be associated with the poem is Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On) now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. It was painted for an Abolitionist convention in 1840 and was a powerful condemnation of the Atlantic slave trade. It depicts the infamous events on the slave ship Zong in 1781. During a storm the crew threw 130 enslaved people overboard before reaching Jamaica; the owners applied for insurance compensation on the grounds that this mass murder was in fact a loss of cargo – the slaves were possessions rather than human beings. In Turner’s depiction, the sea is bathed in the blood-red light of the setting sun; we see hands, legs and chains in the water.

John Ruskin, who owned the painting, wrote of its ‘intense and lurid splendour, which burns like gold, and bathes like blood.’ But even Ruskin downplayed the political content of the painting, and what shocked the Royal Academy was not the subject matter, but Turner’s unorthodox handling of paint and colour.

Turner attached these verses, supposedly from The Fallacies of Hope to the painting:

Aloft all hands, strike the top-masts and belay;

Yon angry setting sun and fierce-edged clouds

Declare the Typhon’s coming.

Before it sweeps your decks, throw overboard

The dead and dying – ne’er heed their chains

Hope, Hope, fallacious Hope!

Where is thy market now?

The Zong incident was nearly sixty years in the past when Turner painted it. Although he was a staunch Abolitionist in later life, as a young man Turner had invested some of his savings in the West Indian sugar trade. He was not alone, of course; George Frederick Handel and Sir Christopher Wren were among many prominent investors in the slave trade. The rousing patriotic song by Thomas Arne, Rule Britannia! (1740), concludes with the words ‘Britons never will be slaves’; evidently no conflict was felt between this assertion and Britons making slaves of others. In any case, Turner certainly had a change of heart; The Slave Ship may have been motivated in part by a desire to expiate his guilt.

Turner was an artist ahead of his time in many respects, but he was more than that. He saw – and painted – both the power and the brutality of the age of industrialisation and colonialism. In Turner’s mind perhaps the ‘typhoon’ was more than a weather event; it could represent the massive power of the forces that were transforming society, in which some will be raised high, and others will be crushed. In the final lines of the verse for The Slave Ship Turner suggests that hope is a marketable commodity in a world in which anything, even human beings, can be commodified. We can buy into the fallacy of hope, but we are likely to be disappointed. Clinging to hope may give us a reason to go on, but no torture, no cruelty, is greater than offering hope and then brutally dashing it.

Was Turner a Romantic pessimist, a cynic, a provocateur, or a brutal realist? The Fallacies of Hope suggests he was something of all of these.

Slave Ship was too big a theme for the modest piece of chamber music I needed to write. I returned to the Venetian paintings, trying to capture a certain quality of light in sound, and a mood that hovers between hope, despair and resignation. It was premiered at the Art Gallery of South Australia in May 2013.

‘J.M.W. Turner and The Fallacies of Hope’ was part of Provocations #4: ‘“Hope” is the thing with feathers‘, a symposium presented by the J.M. Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice at the University of Adelaide on 28 April 2022.