On the second day of 2020, my partner and I caught a train through the suburbs of Munich to Dachau, then a bus to the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site. It was bitterly cold, the morning air nipping our cheeks. Frost crunched beneath our feet and weak sunlight drifted through clouds. At the site, we passed beneath the grim words ‘Arbeit macht frei’, soldered onto the entrance gates (as they also were in Auschwitz and other concentration camps). We moved slowly through the rectangular buildings, reading squares of information about the inhumane treatment of the prisoners. By the time we emerged from the last building, we were weighed down with horror.

We crossed the grounds and walked through a line of bare poplars, the cold eating into our puffer jackets. On either side of us, rows of cement in the soil marked where the prisoners’ barracks had been. The spareness and stillness of the surroundings seemed to harbour the violence enacted on those men: torture, beatings, starvations and humiliation, all designed to eradicate their sense of self. I snapped a picture on my phone of the spindly trees and frost-encrusted soil and added it to Instagram, which I use as a visual diary. Back in Australia, where bushfires were raging, a friend saw the post. She replied: The strangest thing: I just saw an image of the fire-ravaged forest here that looked almost identical to this one.

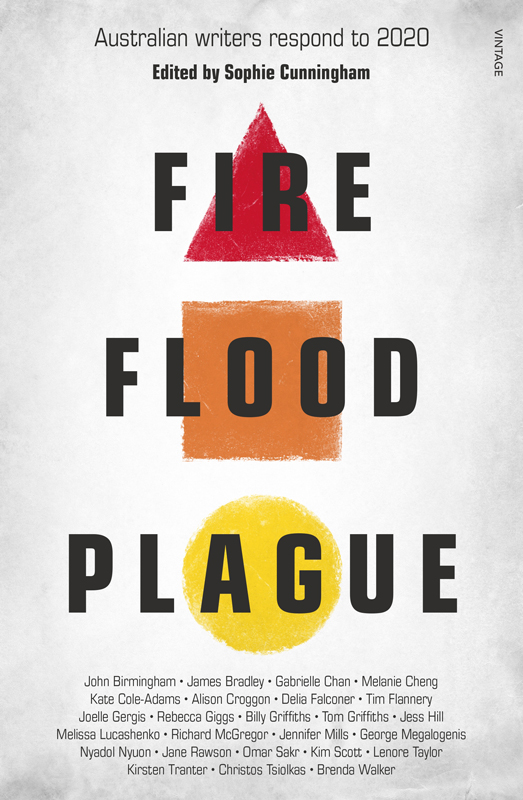

The essays in Sophie Cunningham’s edited collection, Fire, Flood, Plague: Australian Writers Respond to 2020 speak to one another across time and space, the way my friend did to me in that cold place on the other side of the world, from a country slammed with heat, drought and fire. This isn’t so surprising, because disasters, and the writers who comment on them, are connected in an ecosystem. When the virus jumped from animals to humans, prompting the shutdown of so much human intimacy, it seriously disrupted Australia’s arts industry. On 22 March 2020, the day before I cut short my writing fellowship in Munich and embarked on a three-day journey home beset by flight cancellations and border closures, Cunningham wrote of the ‘deeply surreal experience’ of watching ‘one’s entire community experience the evaporation of their working life in a matter of hours.’ She cites a $100 million loss (at that point in time) of gigs, book launches, and visits to bookstores and festivals. As a timeline at the beginning of Fire, Flood, Plague indicates, as artists were losing income and support, the Great Barrier Reef was bleaching again, and this time it was the most widespread ever recorded. This event, another step in the slow death of the world’s largest living structure, was obscured by the panic surrounding contagion and lockdowns, even though some of the root causes are the same: disregard for nonhuman life. The patterns and resonances of Fire, Flood, Plague, its voices calling and responding (to mirror the title of Christos Tsiolkas’s essay) across its pages, point to the way that disaster, while impacting on communities in specific ways, also creates continuities across histories, cultures, and species.

Fire, Flood, Plague contributes to the environmental focus of Cunningham’s oeuvre. It joins Melbourne, Warning: The Story of Cyclone Tracy, City of Trees: Essays on Life, Death and the Need for a Forest and her children’s book, Tippy and Jellybean: The True Story of a Brave Koala who Saved her Baby from a Bushfire, all works which explore place, environment and disaster. The Copyright Agency approached Cunningham to edit Fire, Flood, Plague,and from a list of approximately one hundred authors, she selected twenty-five, featuring archaeologists, scientists, and doctors alongside novelists and nonfiction writers. Each essay was published first in Guardian Australia, before being collated and published by Penguin Random House in December 2020.

The first essay published by Guardian Australia was Melissa Lucashenko’s sharp, fast-paced ‘Too Deadly: Coronavirus in Blak Australia.’ Lucashenko opens with her signature, dry humour:

I’m Aboriginal, so this is where I am supposed to tell you exactly how awful COVID has been for us … Here’s where I write about how the Indigenous poor have gotten poorer still, and the Indigenous sick more wretched. I suppose the dead of all races can’t get any more dead, but in a country where us mob linger at the bottom of every statistical table, how could COVID be anything but yet more terrible, disabling news for the First Nations?

She makes a hilarious segue to mainstream suburbanites in the bog roll wars, then recounts, her tone serious, how several centuries of exclusion, marginalisation and attempted extinction prepared First Nations people to swing ‘into action fast all over Australia’ because ‘survival is what we do.’ While many Australians complained about enforced isolation to contain the pandemic, this experience, Lucashenko points out, ‘is laughably easy compared to being locked in a racist white institution with your psych meds abruptly ripped away, without family visits, without anyone who speaks your Aboriginal language, sans power or dignity or human rights.’ And while the comfortable middle class panicked about their empty shelves or the aforementioned loo paper, ‘plenty of First Nations cupboards were already empty long before February 2020, and will be for a long time after the pandemic is gone.’

Because the virus of racism means fighting for a life ‘not just during this pandemic, but every damn day of every damn year,’ First Nations people gathered at Black Lives Matter protests to express rage, anguish and solidarity, despite the government’s claims (even as it opened schools and malls, Lucashenko notes) that these protests would spread contagion. First Nations peoples gathered ‘knowing there was a small but significant risk from COVID; a risk that was far outweighed by the terrible ongoing cost of white supremacy and murder by cop.’ As Jennifer Mills observes in ‘Trouble Breathing’, a fight for breath is a fight for justice:

The question of who breathes, and who suffocates, is a question of who deserves to live, of who is human. A question of who is part of a community of care, and who is exiled from it. A question that will only become more urgent as the climate crisis develops.

This is not a new question. Archaeologist Billy Griffiths recounts a research visit to Flinders Island where, on a high point near Emita, he gazes down at Wybalenna, the ‘dismal concentration camp where more than 200 Tasmanian Aboriginal peoples were herded and detained from 1833 to 1847.’ It was ‘known to those who lived there as ‘a place of sickness.’’ Griffiths wonders if the pandemic will ‘shift Australians’ historical imaginations’ and prompt us to ‘better grasp the role of disease in invasion,’ particularly given that disease ‘killed some 80 to 90 per cent of the population in eastern Australia.’ The sickness at Wybalenna and Dachau (where typhus was endemic and epidemic) has rippled into contemporary awareness.

At the time that I walked over the ice-encrusted ground at Dachau, I was based at the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society in Munich. Part of my work involved co-editing a special issue of an academic literary journal on life writing in the Anthropocene. One of our contributor’s lines kept ringing through my mind after I read my friend’s comparison of Dachau to the aftermath of the fires: that the Anthropocene is about ‘death on an unimaginable scale.’ It’s not just the deaths of humans but, if we look to the bushfires, the deaths of three billion animals and between three and seven billion trees. As Georgina Reid writes in The Planthunter, ‘and more, again, of shrubs, climbers, groundcovers, fungi, moss; the microscopic and the magnificent. These are quantities hard to fathom, hard to imagine, hard to feel.’

Where Hannah Arendt coined the phrase the ‘banality of evil’ to account for the mass murder of millions of people under the Third Reich, we are still struggling for a way to describe the magnitude of interlocking changes through which we are living. Sophie Cunningham, in her essay ‘Dead Water,’ about the floods on the eastern coast of Australia that followed the fires, notes that the Insurance Council of Australia ‘immediately declared the floods in February [in 2020] as the sixth catastrophe they’d declared in a five month period’ (emphasis Cunningham’s). Little wonder, then, that we are in what has been described as ‘an Era of Disasters, a time “when emergency services will likely be stretched, community resilience undermined, and economic costs and loss of life increased.”’ Environmental historian Tom Griffiths points to the inadequacy of the term ‘Anthropocene,’ which is generally used as a geological marker to define the point at which humans began to shape the planet, rather than the planet impacting on humans. He recommends the use of ‘Pyrocene,’ a time that ‘announces the end of the Age of Ice, the beginning of the Age of Fire, and the end of what was truly the Age of Humans. Not the beginning of the Age of Humans, as is suggested by the smugly named Anthropocene, but the end. And Australia is on the frontline of the Pyrocene.’

It is not just that the comfortable settlers of late twentieth and early twenty-first century Australia have little ancestral memory of extreme biotic, geological and atmospheric events, but also that the bureaucracy developed to manage these events is inept, particularly given the stark difference between Australian and British environments. Cunningham’s observation that the Murray Darling river system has been ‘starved of water and suffocated by a system of bureaucracy that is confusing to the point of being impenetrable’ echoes Tom Griffith’s vivid descriptions of his annual pilgrimage to the High Country in which, looking down from the heights of Kosciuszko National Park, he could ‘see nothing of the world below. In every direction [he] looked down upon a strange, suffocating orange blanket. This was no mystic lake of fog that would evaporate in the morning sunshine; it was something sinister and malevolent, infusing every scarp and canyon with its sickness.’ Meanwhile the mention of ‘sickness’ recalls Billy Griffith’s essay, yoking a history of confinement and brutalisation of First Nations people with the illness of the countries they managed in sophisticated ways for nourishment.

It is not surprising, then, that some writers are finding that Western notions of time and space seem no longer to apply. James Bradley, in ‘Falling’, dwells on his struggle to describe his feelings on the loss of his mother, echoing the struggle for articulation in this strange world. He writes that ‘like all of us I feel undone, unmade, as if time has been suspended, and the world I know is gone. As if I am falling, and have not yet hit the ground.’ Indeed this verb ‘falling’ appears frequently in the essays, and perhaps this is apt if we are, as scientists Tim Flannery and Joëlle Gergis indicate in their pieces, rapidly approaching, or even passing, the tipping point for our planet. Flannery points out that ‘nine of the fifteen known global tipping points have already been activated’ while Gergis is concerned that ‘we’ve unleashed a cascade of irreversible changes that have built such momentum that we can only watch as it unfolds.’ Kirsten Tranter links the white dust that fell in the wake of the burning Twin Towers in 2001 – ‘microscopic particles to dust to snowflake-sized scraps to bits of paper, charred around the edges, the writing still legible” – to the ‘fragments of burnt forest’ falling on Marrickville during the 2019-2020 bushfires. Together these writers reveal associations that readers might otherwise not have seen.

Catastrophes, for all the ways in which they break things up, can strengthen existing connections. Kate Cole-Adams’ beautiful and measured ‘Waiting for a Friend’ evokes the delights of using technology to breathe life into an old friendship as she sits out the pandemic. Revisiting the letters that she sent to her friend in London after she left as a child, she muses, ‘It is almost impossible, I think, to communicate to someone who has grown up with an internet connection and access to cheap air travel the vastness of the expanses between continents. When 17,000 kilometres was exactly that. A letter sent from Melbourne in 1976 could take a fortnight or more to reach London.’ Cole-Adams’ reflections prompted me to think about what the pandemic is like for digital natives. Most of the essays in the collection are penned by writers in their forties and older, and part of me wanted to know what younger people think of the stretch of years ahead that are clotted with anxiety about a carbon-laden future, and about the inequality between rich and poor in Australia expanded by the pandemic.

A collection cannot capture every voice, particularly one that was pulled together in five months, and Cunningham has commented in The Garret on her regret that some subjects, such as the abrasion of the tertiary sector, were not included. There are other Australian Covid-19 ensembles such as Griffith Review’s ‘Through the Window’ series, and AndAlso Books’ Our Inside Voices, which provide views that balance the writing from cities and the south-eastern states in Fire, Flood, Plague. An over-representation of older writers also reveals some common threads, particularly a parallel between the loosening bonds of parent and child, and those between us and our planet. Climate scientist Joëlle Gergis associates the 2019-2020 bushfires with her father’s journey towards death, when ‘an invisible point of no return was gradually crossed, then suddenly, death was in plain sight. We stood back helplessly, knowing that nothing more could be done, that something vital had slipped away.’ Bradley found himself unmoored following his mother’s passing, particularly given the strictures of visiting hospitals as the pandemic gained pace. Christos Tsiolkas recounts his struggle with explaining to his elderly mother the need for social distancing. Perhaps this is, given the difficulty that many Australians have with thinking one or two more generations into the past or the future, a way of explaining the cumulative losses of our epoch: when we lose the ties that bind us, human and nonhuman, we lose ourselves.

Strong emotions jump from the pages of this book, as you would expect from writers sensitive to the injustices striating Australian culture. In the public mourning for the billions of plants and trees, and millions of animals, Kirsten Tranter begins to sense ‘the displacement of a vast inarticulate sorrow at what colonial settlement has wrought for these past 200 years and more. Grief for all those trees and forests cleared, their habitat destroyed, those animals hunted to extinction. The people murdered. The genocide.’ Melanie Cheng, a general practitioner, grapples with the constant dread of infection, her anxiety rising and falling ‘like flotsam, on the wave of that ominous graph’ that charted the infection numbers. These responses contrast with those from the man described deliciously by John Birmingham as ‘our doughy, aggressively know-nothing prime minister’ who, as the past few weeks have reiterated, chooses not to listen, to enquire, to act. As Jess Hill writes in her essay ‘The ghost in the machine,’ patriarchy’s hunger for dominance is facing its limit with ‘what is possibly the most diabolical foe for anyone who values power and control: an invisible and untreatable pathogen.’ I wonder whether, without the destabilisation caused by the virus, Brittany Higgins’ voice would have been heard quite so clearly in 2021.

As I read this book on the bus, on the ferry, or lying in bed, my enduring feeling was rage. This stemmed not only from our flaccid government and often somnolent populace, but my own disability. I have been deaf since I was four, and have frequently observed that often it is people with all their hearing who do not listen. Deaf people, by contrast, cast their full attention towards a speaker so that they do not miss anything. Each time there was a mention of the facts that face us – Tim Flannery’s statement that, for example, ‘in the summer of 2019-20, more than 21 per cent of the country’s forests was aflame’, as opposed to the usual two per cent — my anger resurged. How hard is it to listen, and to act?

So while I identified with much of the writing in this collection, particularly its collective head-banging against a government with a selective investment in knowledge, I did miss the voices of my fellow disabled writers. The Royal Commission into the Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability found that ‘no Australian Government agency with responsibility for disability policy, including the Department of Health, made “any significant effort” to consult with people with disability or their representative organisations during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.’ Already stressed and anxious, they faced additional barriers such as being unable to attend therapy or medical appointments, or to access information (speaking from my experience as a Deaf person, trying to hear people with half their face covered — cutting out most of the information I need to communicate — generated levels of panic and helplessness that I haven’t encountered since I was a child). These findings were made despite earlier research indicating that people with a disability are two to four times more likely to die or be injured during natural disasters.

Yet even at the heart of one the most despairing essays in this collection – Joëlle Gergis’s ‘The Great Unravelling’ – lies a cliché that suggests that d/Deaf and Hard of Hearing people are unaware of what surrounds them. Gergis writes of her distress that ‘everything the scientific community is trying to do to help avert disaster is falling on deaf ears.’ This cliché, which is anatomically incorrect (sound travels in waves, rather than falling) belies the enormous energy that d/Deaf and Hard of Hearing people invest in listening and absorbing information from the people around them.

In light of this, it was lovely to encounter Rebecca Giggs’ meditation on the aural implications of the bushfires and Covid-19, ‘About the Birds this Spring.’ Where, she notes, ‘the peeping of songbirds ushers in the changing seasons across much of Europe, conventional wisdom holds that the squalls of black cockatoos in Australia announce a more immediate shift in the weather – the parrots cry out before a rainstorm.’ I was captivated by this description, perhaps because I have been conditioned by my experience of deafness: on walking through the quiet bushland of Perth’s Kings Park in early summer more than two years ago, I heard a cracking noise, and looked up. Against the bold blue sky was a black cockatoo on a tree branch, chewing on a nut. I have no sense of where sound is coming from, and the only reason I knew to look up was because a woman in my Literature and Environment reading group who researched black cockatoos once told me about their nut cracking. I was inordinately pleased with myself for locating a fellow creature with only a scrap of sense about where it was.

Like every animal, birds are knitted into their ecosystems, and as those ecosystems changed after the fires, so did the birds. Giggs writes, ‘As the vegetation comes back, its sonics will be different. The voices of magpies repeat the sirens of fire trucks, while lyrebirds, proximate to the destruction, have been overheard emulating the engine-chuff of heavy vehicles, rolled in to clear smouldering timber … even after the greenery returns, this new bush will not sound like the old one.’ To a reader who is, by necessity, a relentlessly visual thinker, these observations were both striking and poignant.

Living in London during the pandemic, Giggs noticed how much more people were listening, or rather how bird calls seemed to be louder because the masking sounds of traffic dropped away. She also notes how ‘nurse practitioners, manning hotlines, concentrated for tell-tale hoarseness and consistency to diagnose the dry COVID-19 cough’ and how plagues, in general, create a derangement of the senses (Covid-19 suppresses the sense of taste and smell, for a start). Such attention to our senses might be a useful provocation; a way of shaking loose of the usual ways of processing the information we receive.

In the evenings of the pandemic, Giggs sat on the rooftop above her flat, watching the sun descend and ‘flocks of bird dot and dash the horizon, manoeuvring within rills of weather invisible to me.’ As the birds ‘dissolved into twilight,’ Giggs slowly noticed the lights of living rooms and kitchens below her. In the darkness, she ‘saw how many of [her] neighbours stood at their windows, listening, with me, for what moved in the air between us.’ I was affected by this vignette, because it mirrors the active listening that so many Deaf people practice: an attentiveness to what is so often beyond our grasp.

That Dachau was distressing goes without saying, but I was particularly unsettled by the information that, once the prisoners were liberated by Americans in 1945, people from neighbouring towns were invited into the camp and were forced to recognise what had happened there. Historian Harold Marcuse writes that, as additional punishment, civilians were often put to work, burying corpses and cleaning the camps. Meanwhile a number of the prisoners, once released, had to agitate to create the memorial camp; many people wanted to forget about what had happened.

Australia, too, is beset by amnesia, or a clumsy hold on the facts. According to the Prime Minister, the First Fleet acquired an extra ship as it sailed across the world. Noongar author Kim Scott points out, in his ironically-titled essay ‘One Voice,’ that during Reconciliation Week, purportedly underpinned by the theme ‘In this together,’ Rio Tinto blasted Juukan Gorge ‘into nothingness. A single plait of hair from 4000 years ago, woven from strands of hair from several different ancestors, was as good as unravelled and cast to the wind. One expert compared it to the destruction of sacred artefacts by Islamic State.’ Nothingness and amnesia make good bedfellows.

Scott charts some positive changes that have emerged from the pandemic: the fall of greenhouse gas emissions, the change of pace, an increase in cycling, the recognition of family and friends, people noticing (as Giggs does) the birds. He cites Thomas Kenneally, who suggests that the pandemic might ‘preserve and extend the principles of social democracy that have served us so well,’ but wryly observes that this same social democracy has ‘recently turned its back on immigrants, international students, casual workers, universities, tourism, the arts’ — all people and places that encourage the pollination of ideas. We are lucky to be blessed with a wealthy and compliant society, but it is also clear that the government can listen when it chooses – to the science on managing the coronavirus, for example, rather than those who agitate for change.

Kim Scott suggests that ‘Aboriginal heritage and the natural environment need to be at the centre of any national reconstruction,’ but notes that such reconstruction is fraught with the current ‘neo-liberal context of dog-eat-dog and the primacy of the market.’ For reconciliation to occur, we need ‘respectful, supportive infrastructure. We need the Uluru Statement, and a Voice.’ ScoMo, I feel like saying, are you listening?

In musing on the claims that parrots cry before a rainstorm, Giggs suggests that some truth may lie in cockatoos’ sensitivity to atmospheric fronts, which prompts them to ‘call to gather together and work at tree bark softened by the rain. Some species eat grubs, which they dislodge from the sapwood using their beaks like secateurs. But it might also be the case that the cockatoos’ voices only sound louder in air of rising humidity, fenced by low, dense rainclouds – the surrounding conditions, then, not the birds’ calls, herald the advancing meteorology.’ We are edging unsteadily out of the pandemic, into the rainstorm, into a world in which we might, finally, be able to hug with abandon. Fire, Flood, Plague, and others like it, have magnified voices that speak to the inequities of Australian society. Will we ignore those voices and sink back, stupefied by the cry of capitalism, ‘Work sets you free?’ Or will we listen to them, amplified by circumstance, by the oncoming shock of thunder and rush of rain?

Works Cited

Cunningham, Sophie. ‘At Home with Sophie Cunningham.’ The Garret: Writers on Writing.

Marcuse, Harold. Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. ‘Disability Royal Commission recommends changes following COVID-19 hearing.’ 30 November 2020.