John Mateer, over a long career, has been a poet of distance and locale, working with a continental sense of poetics, traversing land and sea in an inquiry into the nature of an historically-framed instant. His early poetry, anthologised in The West, (2010) displays an engagement with the ancient continent of Australia, exploring the embodiment of history as it is revealed in the structure of particular landscapes, their plants and terrain, and their essential remoteness. ‘Towards Wilpena Pound’ and ‘On a Coastal Walk’ are examples of early work setting the standard for themes to come, with their awareness of the interconnectedness of history, place and self:

Trudging across an inlet with the water tide rushing in

my boots slurping the sand

the water detonating then foaming and fanning over the hump of beach

over my boots the cold surface bubbling forever and an instant

like trillions of equidistant molecules between which this

was annihilated –

The landscape poems in The West are not rendered in passivity, contemplating a view, but are actively walked over, emphasising the encounter in all its fraught and traumatic nature; in ‘On a Coastal Walk’ ‘the cold surface bubbling forever and an instant’ captures eternity, the continent’s tragic narrative and the walk itself within the momentary.

Southern Barbarians (2011), by contrast, inhabits oceanic voyages of exploration, as the poet moves with an elegant sweep over distances with, as in ‘The Allegory’, ‘silver seafarers/on a black ocean of Mind’. The poetry is predicated upon the melancholy of those distances, of encounters which in their singularity adhere to a wider theme of continents crossed, empires faded, illuminating a rich fabric of the notions of exile globally performed. Whether, as in ‘The Discovery of Japan and of the Boomerang’, ‘a dark Chinese junk, torn by evil weather, … driftwood loitering on a falling dawn tide,’ or at the southern margins of Portuguese exploration, in ‘On eventually finding near Geelong the memorial commemorating three keys thought lost by Cristovao de Mendonca, circa 1520’, or ‘On seeing the replica of a ship believed wrecked near Warrnambool, also circa 1520’, we encounter a sense of melancholy and abandonment. In the recent inter-continental collection João, the poetry moves in other directions both formally and thematically, with the sonnet form enclosing the momentary in an acute snapshot of essentially fraught and disconnected but ultimately luminous wandering.

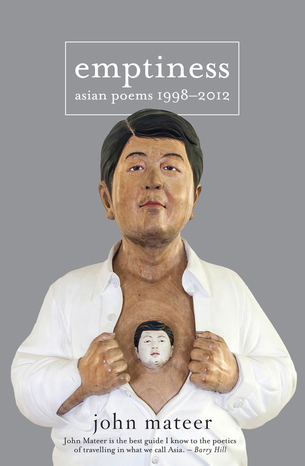

In Emptiness (2014) Mateer steps ashore to contemplate the metaphysics of geographies. Consisting essentially of a number of small volumes devoted to specific locales, and wherever possible translated in separate publications into the local language, the chief characteristic of Emptiness is an exploration of the nature of the image. This extends beyond the Modernist ‘thing itself’ to a sense of its ambiguity as a possible not-itself, a sense of its contradictions both historical and perceptual. The image, lightly tethered to history, reveals itself as a site of disruption. As the poet has said, in an interview with David Shook in 2013, he sees place

as being an embodiment of history. I see it in almost the Buddhist sense of pratitya-samutpada, that is that conditions produce phenomena – and so for me place is deeply connected to person and history.

As such, the poem is transformative of person and history, as poet and place meet, it resonates, transforms. In Buddhist philosophy, sunyata is often translated as emptiness, or as the void, denoting both the nature of, and the analysis of experience.

An important section included in Emptiness is ‘Mu No Basho’, which was also published in Japan in a bilingual edition, The Ancient Capital of Images, with translations by Keiji Minato. The title itself, translated as ‘place of emptiness’, derives (according to the poet in a private communication) from the philosophers of the Kyoto school, specifically in the work of Nishida Kitao. The school looked to Western links to Japanese philosophy, with a consideration of the thought of the Zen master Dogen (1200-1253), which predicated the realisation of emptiness through zazen, or meditation practice, and the ‘being in the world’ ethos of Heidegger and the phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty. By referencing the Kyoto school in this way, Mateer hints at a thread of a connection between Eastern and Western patterns of thought.

If we were looking for a collection within the poet’s extensive body of work which most exemplifies his aesthetics, we could find it here in ‘Mu No Basho’; it is telling that the complexity of the momentary paradoxically involves a long prior process of concentration, a feeling or sensation which the momentary then reveals in its particularity. This structure can then encompass a response to or a questioning of the image’s exigencies. It also, importantly, can conflate the distance between the embodied speaker and place, so that one can melt into, or be barely indistinguishable from, the other.

An example of this effect can be seen in ‘Dead Leaves in Tokyo’, where there is a doubling of the artefact of the poem, a kinetic imagining. Fallen leaves ‘collected from the garden of museums and temples’ ‘under intense light on a city desk’ exist in the mind ‘perpetuated in aquarelle’, and with a sudden turn in direction (often occurring in Mateer’s poetry to either question, or to look back on or riff away from what has been said), ‘The poet’s mouth opens slowly, releasing the leaves and the wind/that these words are.’

Another important factor to consider is the effect of the visual arts upon the poetry, working in tandem with the philosophical. At an Asialink event in 2010, Mateer referred to the photographer Hatakeyama’s Blast series as an inspiration for the poem, ‘Autumn is Everywhere’, which like ‘Saigyo’s Cherry Tree’, expands upon the kinetic surface to suggest the poetic equivalent of a video installation moving at slow speed. The exchange between place and body is a connection explored to the very limits of existence, in effect to ‘the conundrum of the Instant’ where existence and non-existence reside together:

Even in an explosion

if you have the right shutter speed: the shards of rock— projectiles — will become fluttering leaves decorating an icy wind.

Autumn is everywhere. Autumn is your skin flaking,those shards becoming boulders offered to the eye

of an electron microscope, becoming food for dust mites,becoming the conundrum of The Instant:

How can moments, things, have an independent existence?Yet, if found among the scattered remains of an explosion,

the shards of my canines and molars will prove my existence.Everywhere I look the avenues of trees ae exploding in slow motion.

The repetition of certain phrases across a number of poems beginning with ‘The Ancient Capital of Images’, gives a sense of visual sequencing, with the effect culminating in ‘Saigyo’s Cherry Tree’. Here, ‘The colour of the momentary/that’s what they’re photographing out there in the blinding world’ is repeated three times before making a linking, or montage, to an atomic explosion:

And I’m waking to remember that one hibakusha,

in a letter to his wife’s spirit, evoked their fateful moment

as an enormous blue-white flash,

as when a photographer light a dish of magnesium.

The appearance and disappearance of imagery set up and intensify a morphic field of sensation. In this extraordinary distillation of the poetics of emptiness, images of the camera lens, the retina or the television screen add to the doubling of perceptual inquiry across the page. With an exploration of the image through a focus on kinesis and the deep interiority of mind, a grouping of four poems under the title ‘The Ancient Capital of Images’ appear almost as a sliding screen of images which, in their beauty and malevolence, repeat and extend the image in a lyrical meditation on past and present. Presenting as they do an intimation of another world, the poems momentarily display a transference of the imagery of the floating world to a sense of self in the very act of writing. Imagery from the pornographic to the erotic give texture to a narrative that highlights the presence of a geisha, almost an intermediary between worlds:

Behind my eyes,

A geisha in the crowd at the Saturday night traffic lights,

her kimono a golden brocade landscape, her skin a primal white.

Kinkaku-ji, the Temple of the Golden Pavilion, was built in 1397. It was famously burned down in 1950 by a novice monk, an event which became the subject of a novel by Yukio Mishima. ‘On Seeing Kinkaku-ji’ portrays the image of the temple as possessing a kind of fragile yet robust nature. Situated on a pond, its doubled image, ‘the Real and its/reflection is also situated, tentatively, in the mind:

Upside down on your retina, on the nerves deep in the black box

of your skull,

the Pavilion, radiant, wobbling, gently righting itself,

like a tethered boat after being disturbed by a passing wave.

The second part of the poem draws a delicate line between conflagration and absence on one hand, and a hardy, glorious presence on the other:

Unlike Mishima’s antihero, you don’t wonder whether beauty is

the burning pavilion

or its surrounding void…

…you notice that on the apex of the roof

of this treasure once torched by a monk,

there stands, arched and alarmed, an airy, comic phoenix.

If in this poem what is transmitted to the reader is the subjectivity of the poet caught up in the watercolour as it were of its presence, in ‘Under the Temple’, Mateer takes the reader further into an image’s possible nature. Situated ‘under the thick floors of Zenko-ji (built in the seventh century, and one of Japan’s oldest temples) where the poet is under the influence of the recitation of the Prajnaparamita or Heart Sutra, he experiences sentience ‘reduced to my right hand’, along with a sense of place barely registered by ‘the crystals of our inner ear’. Turning in this ‘blacked-out passage’ and surprised at ‘what we are withdrawn from’ in an age ‘burning like a neon mansion’, he ends the poem spectacularly with a play on the conundrum of darkness and light, of the suggestiveness of emptiness: ‘The blindness is a golden wilderness’.

Osore-zan is a mountain in the volcanic region of northern Japan that, with its charred and steaming landscape and its desolate aspect, has long been viewed in Japanese culture as an entrance into hell. Its unique nature has attracted a number of practitioners, including the video artist Bill Viola, and the poet Yoshimasu Gozo. In an interview with Aki Onda, Gozo describes the effect that Osore-zan has had on his work, particularly in relation to the chanting of the blind shamans once present there. He observes that ‘It really is an intermediate zone between two worlds’. In Mateer’s ‘Osore-zan’, a moving encounter with personal loss, and a dramatically Buddhist mise-en-scène of mourning takes place:

Nearing the edge of the crater lake, that dead mirror,

I observed my existence here, that in this no-man’s land,

this Bardo, on this, another mountain, I was seeking my lost

The poet, ‘watching my reflection drifting over the jaundiced ground, … ghosting through the blank banners of sulphurous smoke’ sees in this mountain another one, with ‘my father’s ashes cast to the wind on an African mountain/in his family’s absence, the wasteland of my childhood – ’. It is apt to refer here to a sonnet in the ‘Memories of Cape Town’ section in João, where the African mountain referred to in Osore-san, a desolate place ‘where his Dad, long gone, had taken him,’ a place where men ‘wandering up the Mountain until mist or dark/descends, forcing them into caves, sleep’s wilderness’.

In ‘Mu No Basho’, with the mingling of the contemporary and the historic within the context of what is both familiar and unfamiliar to the Zen practitioner, the poetry presents itself as artefact, as a staged construct, as a resonant ‘made object’ which frees language from the restrictions of temporality, to become seen and source, a place of emptiness.

As Jamie James writes in The Glamour of Strangeness, Victor Segalen remains an undervalued figure in Modernist literary history. His Steles pre-dates Ezra Pound’s incorporation of Chinese characters into his poetry, and his prose work was also exceptionally innovative in its both its inclusion of multiple time sequences, a crossing over between journeys real and imagined as in his Equipée, Voyages au pays du réel, and in bringing the reader into the discourse, as in Paintings. Segalen writes,

One must look deeply into oneself, even strain a little, to find something new of one’s own, the unforeseen, and the incomparable shock of the Diverse, in places where people who write and speak the same language have lived together for a long time.

In his obsession with steles, and in his desire to encounter, in his explorations in China, the face of a Han warrior, which in a meeting of stone and flesh would in effect be a mirror image of his own, he may have experienced disappointment in the excavation of many a headless statue, but his work, other than its quality, is an ongoing gift to poetics. He was not alone in his obsession with ancient sculpture: Pound, Gaudier-Brzeska, and Wyndham Lewis all sought to incorporate the lessons of ancient cultures into their works’ formal properties, be it in literature or art. Segalen’s Steles manifests on occasion a dialogue between stone and calligraphy, a merging of poetry and prose printed, as James notes ‘on narrow pages that approximate the shape of ancient steles’.

Segalen’s exploration of what James terms ‘the troubled frontier between imagination and experience’ has some parallels with the Chinese-centred poems in Emptiness, entitled ‘Mirror’. Some of the poems have a calligraphic impact, and a tension between the vivid and the unsaid, or unarticulated, which becomes invisibly present. A dialogue ensues between face and facelessness, trace and erasure, writing and blankness, presence and ghostliness, a journey in a sense reminiscent of the form of a Zen koan. ‘Steles’ is an exceptionally complex poem which in registering a blankness and a ruin, takes on the play between the inscribed and the uninscribed, a site where ‘The Forest of Steles in memory/is the razed house of the Poem, where ‘a pen dipped/in water’ proclaims ‘I AM THE MOMENT.’, where the notorious Empress Wu’s ‘Wordless Stele’ implies ‘Perpetual fear.’

As Mateer has written in his essay, ‘In the Chinese Mirror – Victor Segalen and the Quest for the Chinese Face’, Segalen ‘seems to have sought in the ancient Chinese past a face that might mirror his own, a portrait of a Han man, a warrior-poet of the earliest grand phase of Chinese civilisation’ but the search for this ‘mirror-image of himself’ resulted in finding a statue missing feet and, significantly, headless, an encounter which Mateer characterises as ‘an impersonal absence.’ In his belief that ‘Chinese civilisation could be a solution to the decadence of modern European culture’, which was certainly part of the Modernist project, he was possibly ‘seeking stasis, an escape from the modern and its violent, endless change.’ Segalen did in fact find a face, but it was the face of a captured soldier, trapped under a horse. ‘To Segalen’ presents a literary connection across time, a certain sympathy of poetics:

Let Name be between voice and face.

Let Name be the void

between the speaking Dead

and that impossible Han portrait

sought in the China of Self.Don’t be found there under that squat stone horse,

barbaric, trapped in the rictus that is likeness,

a cipher printed by an army tank.

Don’t –

In João, the poet travels to Xi’an to see, framed by a polluted and contemporary city in the throes of development, the ‘small terracotta army prepared for fighting ghosts,/or whatever’s in the Afterlife’ in order to ’behold their miniaturisation that hosts/memory and dream.’ Historically earlier than Segalen’s beloved Han, ‘These figures and their shadows the insisting/that we humans don’t live in our skulls’, these ‘clay warriors’ ‘dedicated to the habit of war’ return the poet to the spirit of Zenko-ji and Emptiness: ‘Joao tells himself: ’Become Nothingness, that golden wilderness!’’

One difficulty in the Modernist idealisation of select ancient cultures is that their art was seen as formally exemplary, that in their stasis they were providing inspiration to a movement that was anything but. The insights of Appiah and his espousal of the ‘contamination of cultures’ is apt here. In ‘Mirror’, the appreciation for Segalen’s ethnographic and literary achievements is countered by poems alert to the shifts in culture both historic and artistic, which render any sense of a ‘pure’ culture moot. As Mateer mentions in his Segalen essay, the writer discounted the long history in China of Buddhist art, seeing in its derivation from sources in India and Central Asia, and significantly its two-dimensionality as what could be called a derivative hybridisation of form. In some sense this view undermines his own project of cultural incorporation into his own work, and adds to the weight of Appiah’s sense of inevitable ‘contamination’ or transference of culture. Although respect for Segalen shines through in ‘Mirror’, this is not to say that the poetry is unaware of the representation of hybridisation; on the contrary it is a consistent theme through the collection (as in Mateer’s work as a whole. Poems such as ‘In the Muslim Quarter’, ‘The Demon’ and ‘Ruin: An Essay’ reference historical and political intervention revealing a variety of devastation, where, to quote ‘The Demon’, the momentary can be inscribed by a ‘demonic calligrapher’. Ghostly presences perform a very human connection in poems such as ‘Ghost Wedding’ or wander through Xi’an in ‘Among the Muslims’, while the poets in ‘Ruin: an Essay’, are close to being so, where ‘at an unofficial poetry reading’ a photograph obscures their faces ‘to protect their identities’.

Dogen, when he was dissatisfied with the contemporary teachings on offer, made his way to China, and returned with his own take on consciousness, and how zazen held within it the possibility of the realisation of emptiness. There is a long history of cosmopolitan seekers tracing their way through the thickets of possibility in Asian countries. In regional solidarity, may this tradition continue, as it does within John Mateer’s Emptiness. The joy of reading Mateer is that there is no easy way to approach the multi-faceted poetry, compounded by the quality of its having a commentary on its nature is encoded within it. The final poem in the volume, ‘Landscapist’, in its vividly portrayed ekphrastic impetus suggests an accessibility available to the reader, as it presents sufficient detail for some kind of reckoning. However, like Segalen:

Your hand, dear Reader,

wants to pass over

this picture, this mirror,

but can’t.

It is a wall untouchable,

recently painted. Besides,

you don’t exist.

As in ‘The Ancient Capital of Images’, in Nanzen-ji:

GO FURTHER —