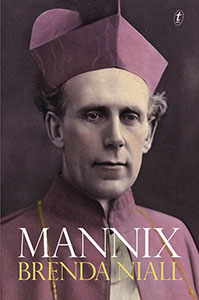

It was possible in the 1950s for a small Catholic child to see Daniel Mannix, the Archbishop of Melbourne from the time of the First World War, driven down Burke Street on St Patrick’s Day in an open Rolls Royce, his hand waving gently like royalty, the lean, high cheek-boned face still striking beneath the vivid biretta of a purple so light it might as easily have been red. He was in his tenth decade, but a child is no judge of the extremities of age. If ever a man looked like a prince of the Church it was Mannix, though he was denied the Cardinal’s red hat for, as he said himself, ‘If I had ever wanted to be a Cardinal, I would have charted my life very differently.’

Daniel Mannix is the greatest churchman in Australian history, but he was far too much of a turbulent priest for the College of Cardinals. This was the man who opposed Billy Hughes’ referendum on conscription and won. This is the man who split the Labor Party down the middle in 1956 and did everything in his considerable power to keep it out of office.

He was born in County Cork in 1864, during the American Civil War, and he died 99 years later in 1963, the year Kennedy was assassinated. He came to Melbourne in 1913 when he was kicking 50, having been President of Maynooth, the great Irish seminary in County Kildare, 25 or so kilometres from Dublin. In James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), there is a reference to ‘my lords of Maynooth’ and to the fact that in their catechism they define the legacy of original sin as ‘a strong inclination towards evil’. It is pleasing to reflect that the overlord at Maynooth on 16 June 1904, the day when Joyce set the Odyssean journey of Leopold Bloom’s tramp around the city, was the man in the top hat and frock coat who walked every day of his life in Melbourne until his ninetieth year from his residence, ‘Raheen’ in Kew, to his St Patrick’s Cathedral on the eastern hill that overlooks the city.

Brenda Niall, the distinguished biographer of the novelist Martin Boyd and author of a swag of other books, has written a fond and fluent life of Mannix that captures the crispness and the passion, the humour and the enigma of the man who meddled with politics like a master magician. When Arthur Calwell looked like being locked out of the prime ministership, he declared that there was little chance of a Labor victory short of a visitation from ‘the Angel of Death’, by which he meant Mannix’s demise. In the 1950s, when Mannix turned against the Labor Party because of the Communist influence in the unions (which sparked the Split not least because Mannix’s lieutenant B. A. Santamaria had a counter-insurgency going on in the unions), Mannix declared:

Every Communist and every Communist sympathiser wants a victory for the Evatt Party … That is alarming.

This was 1958, and the Nation correspondent could only surrender to the sheer theatre of the politics:

Connoisseurs of the long career of Archbishop Daniel Mannix threw up their hands in appreciation the other day at the vintage quality of the election eve statement made by the 94 year-old prelate to spike the hopes of the Australian Labor Party. There could be no imitation of the real thing. It made 1917 seem only yesterday; the seemingly controlled scorn, the deadly timing and above all that special blend of bluntness bordering on crudity of argument with a daring astuteness of presentation that forestalls the ability of even senior prelates expressing public disagreement lest their church should become a battlefield.

There was an insolence of genius in that phrase, ‘the Evatt Party’.

Ireland and the sorrows of Ireland had always been Mannix’s blacking factory. Manning Clark described his appearance in 1957:

His face was heavily lined, [his] cheeks sagging though not flabby, the eyes moist, tinged with a faded yellow, a thin line of red along the edge of both eye-lids. The general effect, in repose, was impressive – solemn dignity which often collapsed into an impish twinkle or chuckle. He coughed a lot. His voice still bears an Irish accent though not often – pitch, generally a mumble at low pitch. We talked at first about Cork and I muffed my first compliment. Later, much later, when with more confidence I told him the people of Cork looked on him as one of their proudest sons, he said scornfully, though with that impish twinkle, ‘They must be short of people to admire’ … he looked like a man for whom it all happened years ago, and like a man who has been stunned, knocked down by a great force, but had the courage, the faith, to stand up to his oppressors & not to whine in the gutter – supine – and a sadness deep down because he could not understand why it had happened to him and Ireland.

Mannix wrote these plangent words to his priestly friend William Hackett, one of his only confidantes and the man who had been a crucial messenger between Michael Collins and his henchman: ‘You will come another time and we shall sit by the rivers of Babylon and weep when we remember Sion.’ But somehow that memory of an Irish Sion made him an activist in the Australian Babylon. It was his Irish radicalism that turned him into an Australian patriot. Here he is on the executions that followed the Easter rising in 1916:

Men said to be innocent were put against a wall in a Dublin barrack yard, and without trial by judge and jury, were shot in cold blood and sent before their Maker. These outrages will rankle in the minds of men and they are not likely to bring a blessing upon British arms.

And here is one of his speeches, which is all the more powerful for the way its fire is pulled back:

I am as anxious as anyone can be for a successful issue and for an honourable peace. I hope and believe that peace can be secured without conscription. For conscription is a hateful thing, and it is almost certain to bring evil in its train …

The Prime Minister has very wisely avoided evil counsels and allowed the people to decide for themselves … We can only give both sides a patient hearing and then vote according to our judgment. There will be differences among Catholics, for Catholics do not think or vote in platoons, and on most questions there is room for divergence of opinion. But for myself it will take a good deal to convince me that conscription in Australia would not cause more evil than it would avert. I honestly believe that Australia has done her full share, and more, and she cannot reasonably be expected to bear the financial strain, and the drain upon her manhood, that conscription would involve.

Mannix was, by temperament, a liberal and he had a horror of bloodshed and injustice. Niall tells the story, a wholly uncharacteristic story because of the nakedness of the emotion, of when Mannix first heard of the 1916 reprisals. ‘Michael, they’ve shot some of them,’ he exclaimed in tears as he told the news to the handyman at St Mary’s, West Melbourne. He decided then and there that there would never be Home Rule for Ireland; it had ceased to be a just solution because the brutality of the British had proved the rebels right. Billy Hughes declared that Mannix was a Sinn Féiner and that he was in two minds over whether to deport or prosecute him. Niall makes much of the extraordinary story of how some twenty years later, in 1937 – after Billy Hughes’ daughter had died in childbirth in London – Mannix, who may have been privy to the circumstances and arranged for the child to be looked after, greeted the Little Digger (to the amazement of his housekeeper) at the door of Raheen, the gaunt old Fenian putting his arms round his old enemy. They remained on friendly terms until Hughes’ death at the age of 90 in 1952.

The terms on which Mannix met the world were always his own. He would not dine at ‘Bishopscourt’ with the Anglican Archbishop; he would not dine with or visit anyone. When Lord Summers wrote to him offering hospitality, he replied with an elaborately wily courtesy that does not mask the steeliness of the sense of self behind his resolve. If he was a politician for the Lord (to use a phrase beloved of that clerical master of Ormond College and Governor of Victoria, Davis McCaughey), he could be an unbending one:

You have made it hard for me to write this letter, for it must seem ungracious on my part to say that I never go out to lunch or dinner. But your quite unexpected and truly generous invitation almost tempts me to break my self-imposed rule of living & most of my resolutions are often broken. But I have been faithful so far to this one. Your Excellency therefore must not become the cause of my first fall from rectitude in this matter.

The elegance and courtesy cannot conceal the coolness. This became cold fury when Mannix turned the full force of his concentration on Ireland during the extraordinary period when the British Government deemed him too dangerous to enter his homeland, despite the presence there of his aged mother.

Mannix became a committed Republican and a backer of Eamon De Valera, against the more temperate counsels of people, like Michael Collins, who had compromised with the British and were happy, at least transitionally, with the Irish Free State. He did nothing to moderate his sense of British perfidy and persecution during his tour of America, which was designed to inflame the sensibilities of Irish Americans:

There is no use mincing words. Ireland is ruled by an alien Government. I see no way out but American recognition of Mr de Valera. Some have said that England is a friendly nation. No, England never was a friend of the United States. When your fathers fought it was against England. Ireland has the same grievance against the same enemy only ten times greater. I hope Ireland will make a fight equally successful. England was your enemy; she is your enemy today; she will be your enemy for all time. England is one of the greatest hypocrites in the world.

This is extraordinary stuff from a man who had once been tipped as a future Archbishop of Dublin, and whose ecclesiastical countrymen were busily condemning those of the Irish who would not accept the Free State and were continuing what was now a civil war. Mannix declared that he was for Ireland and the martyred dead:

I am going to Ireland soon and I’m going to kneel on the graves of those men who in Easter Week gave their lives for Ireland.

The British would not, however, allow him to make the crossing because they saw him as a blatant provocation to sedition, never mind his old mother. His boat was stopped in the attempt to cross and Mannix made a fine play of this in the British press. The London Times quoted him on 11 July 1921 saying that there had been nothing like it since the Battle of Jutland and the triumph of ‘the capture, without the loss of a single British sailor, of the Archbishop of Melbourne’.

The British Prime Minister Lloyd George offered to allow Mannix’s mother to come to England to see him and there is no doubt she wanted to. But Mannix disdained the political compromise and was never to see his mother again. When Gerald Lyons interviewed him in 1963, the year of his death, on ABC Television – at that the time the longest interview ever to be broadcast in Australia at 90 minutes – and asked him how he felt about this, Mannix held the silence for longer than his old man’s slowness had dictated on other occasions. Finally, he said: ‘I have forgiven, but not forgotten.’

Meanwhile the Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork had been murdered by the Royal Irish Constabulary acting on British orders and had been replaced by Terence MacSwiney, who was arrested for possession of seditious papers and given a two-year gaol sentence. In Brixton Prison, MacSwiney began a hunger strike. Fellow bishops considered his death suicide and therefore a violation of Catholic principle, but Mannix performed the last rites for MacSwiney, said a requiem mass in Southwark Cathedral, and led a procession of 10 000 people through the streets of London in the presence of mounted police. He walked at a respectful distance behind the hearse and as the coffin in Sinn Féin colours was put onto the train he recited the De Profundis (’Out of the depths I cry, O Lord’), the ‘Líbera me, Dómine’, the Requiescat.

This is one of the moments when the iron enters Mannix’s soul:

If Ireland’s cause is a just and holy one, as I believe it to be, then I think the Irish people have a right to look to me, Archbishop though I be, for something better than lip service. For I am bone of their bone and flesh of their flesh.

In 1925, he gave Ireland his long farewell. On 29 June, romantic Ireland came out to fête him: Maud Gonne MacBride, Yeats’ muse and the martyr’s widow, and Constance Gore-Booth, the Countess Markievicz, but not the bishops. In Cork a light mist fell and a procession of people carrying turf-lit torches made their way, leading the archbishop to the church in Charleville. It was locked and utterly dark. The gates of Maynooth, his old bastion, were closed against him. He said to his cousin, John Cagney: ‘I’ll not give them the chance to insult me a second time.’

Mannix suffered insult but did not return injury, though there is no denying that this monk without a monastery was a man of flint and that opposition was his essence. He remarked that Billy Hughes ‘called me a liar and a traitor and a rebel, but I always called him Mr Morris Hughes’. Yet in Mannix’s mouth the currency of courtesy had its sting.

Brenda Niall says the cloisterless monk was always a politician without a party and it was probably inevitable that Mannix would, like Hughes himself, first turn to Labor and then turn against it. As that establishment Englishman, Cardinal Manning, had marched with the striking dockers in London in the 1880s, so Mannix backed the Seaman’s strike of 1919. His eloquence was potent. Just two years after Lenin came to power in the Russian revolution, his sentiments are radical and socialist, however rooted in common sense and Christian compassion:

Would any of the sneering critics undertake to balance the family budget on the strikers’ wages, and at the present cost of living? Would they live in the conditions, in the holds or in the slums, on sea or land, in which these strikers had been living? … The sooner people realise that the worker must get not merely a living wage, but a fair share of the work that he produces, the better. The sooner people realise that men and women and children count for more and are more sacred than property, the better it will be for the community.

But if the Archbishop was bolshie in his commitment to a redistribution of wealth, the former professor of moral theology was no lover of communism, perhaps because of its godlessness. Niall, who is manifestly Catholic in feeling, and who talks about working (non-politically) on one of Santamaria’s magazines, and who interviewed Mannix as a young woman in the 1950s, says that his horror of left-wing totalitarianism was greater than his fear of the right-wing variety. She also details his plea for the Jews in the 1930s: ‘The Jews are being hunted,’ he said, ‘pillar and post out of Europe.’ And, he said, the Jews were ‘a great people’.

Still, it was Bob Santamaria, the man who had put the case for General Franco to cries of ‘Viva el Cristo rey’ at the great debate at Melbourne University in the 1930s, whom Mannix chose as his Jacob. At the very outset of her book, Niall says that Mannix remarked to her that ‘I think Mr Santamaria is the cleverest man I ever knew’. She recalls her bewilderment at his emphasis. Mannix seems to have liked the outsider in Santamaria as he liked the outsider in DeValera, right down to the fact that each of them had names that might have been plucked from the ranks of the grandees of the Spanish Armada bent on conquering England.

Santamaria seems – not surprisingly – to have been awed by Mannix, but also attracted to his archiepiscopal dominion in a way another person might have shunned. Mannix was no lover of clerical hierarchy. At the time of Norman Gilroy’s appointment as a Cardinal – Gilroy the telegraph boy from Gallipoli, Australian-born and conventional – Mannix knew he had been betrayed. He was disliked by the Apostolic Delegate Archbishop Giovanni Panico, who insultingly remarked, when Mannix was rejected for a red hat, that he looked forward to the day when all Australia’s bishops would be Australian. Mannix rose to thank him at the celebratory dinner and said in tones of grave courtesy: ‘I would like to say that I look forward to the day when the Apostolic Delegate will be Australian.’

So when Santamaria was becoming involved with the Australian National Secretariat for Catholic Action, Mannix was bemused by his suggestion that they have a priest to help them avoid mistakes. ‘You will have heard,’ Mannix said, ‘that the man who makes no mistakes makes nothing.’

The irony is that Santamaria, who was to cast such a long shadow over post-war Australian politics (one that arguably still touches the prime ministership of Tony Abbott), did his work with the collusion and the supervision of the man who by force of personality was thought of as the highest priest in the land. Mannix made Santamaria the deputy director of his Catholic Action group, which led directly to the Movement, which was very deliberately engaged in combating Communist influence in the unions and the Labor Party. The so-called Groupers – the industrial groups that formed the mirror-image fifth column in the Unions – would completely transform Labor politics and would, all too successfully, battle the left-wing influence in the party, which had been given some degree of credibility by Russia being our ally in World War Two.

Mannix was prescient about Stalin’s sweeping takeover of Eastern Europe and spoke of ‘the blanket of silence over the annexation of Poland’, but (in one of his few dissensions from Santamaria’s position) he refused to back Menzies’ anti-Communist referendum seeking to ban the party in 1951, and voted no himself. He did, however, back Santamaria to the hilt over the unions and the Labor party, even if there will always be debate over how the wily right-wing ideologue manipulated the very old radical. Not much, one suspects, though the detail of politics is not Brenda Niall’s emphasis. When Mannix went through the motions of entertaining a potential donor to the Movement, he bade him farewell with the words: ‘Well, I’ll say goodnight to you now, Mr Broderick – and go in and count my spoons.’

The myth is that ‘Raheen’ was bought for Mannix by John Wren, the businessman who was the ostensible target of Frank Hardy’s Power Without Glory (1950), that work of socialist realism which is, as Niall says, primarily an attack on the Movement, and which also depicts Mannix. But ‘Raheen’ was not Wren’s gift, it was Mannix’s chosen retreat and citadel.

It is worth remembering that up until the Split in 1956, H. V. Evatt, the leader of the Labor opposition, was still keen on maintaining Mannix’s support – ‘I appeal to your Grace for help in accord with all you have done for liberty and justice in Australia’ – and was receiving it, tepidly in Mannix’s case, and with even greater lack of enthusiasm in the case of Santamaria. The Communists in the unions were aware of the actions of the Movement and the Groupers, but could not expose them without exposing themselves. Arthur Calwell, a Catholic and for a long time a great admirer of Mannix, loathed Santamaria and his influence, but could not attack him without seeming soft on communism.

Evatt, who Santamaria described as a man without a soul, attempted to do a deal with Mannix and Santamaria, but then the Petrov case blew up in his face. Here was this poor woman who was being dragged back to darkest Russia, only to be rescued by Australian customs officers. Menzies succeeded in using the case to make Evatt appear the dupe of faceless men, and hence wide-open to Communist influence. It was certainly true that Santamaria was poised, in the event of Evatt losing the 1956 election, to make a bid for dominance with his Groupers.

In practice, Evatt lost his balance – there was the insanely misjudged evidencing of Molotov’s assurances and the Labor leader’s crazy decision to appear as defence counsel before the Royal Commission. And then there was his venal strategic and back-to-the-wall attack on the Groupers and the Movement which made Santamaria declare, with Mannix’s firm support, that he would fight back – hence the Split in the ALP, and the formation of the DLP as an agent of influence and a force for fissuring and entrenching the parlous state of the Labor Opposition, which did not gain government again until 1972.

In the midst of all of this, Cardinal Gilroy, the Archbishop of Sydney, got a ruling from the Vatican against the activities of Mannix and Santamaria and the Movement, which led the 90-year-old turbulent to declare, ‘Rome has blundered again!’ In one sense, they had. In another sense, he was in thrall to his own ideological mystery. It depends on how much you distrust Santamaria and his weird and brilliant technique of mirroring Communist secrecies and stratagems. My father, who was a journalist and had been attracted to the Left as a schoolboy, loathed Santamaria and the Movement because of its clandestine penetration of the Labor Party, even though, despite his Labor instincts, he voted for Menzies throughout the 1950s. Yet he sometimes went for the DLP in the Senate, because he felt they mitigated the coalition in the direction of social justice.

Mannix always decried the idea of the Movement as an anti-body or virus within the Labor Party. Here he is at the age of 90 replying to the charge:

If the Labor Party is brought down in ruins the fault will not be mine. I have done what I could to prevent political folly and disruptive sectarianism. I notice that reference has been made to Catholic Action groups within the unions. They are not Catholic Action groups; they are industrial groups. There has been a lot of talk also about ‘action from outside’. These groups are not acting from outside, they are acting from within, as the communists are working from within.

Still, in a moment of sinning against his own nature, he consented to censor the Catholic Worker, which opposed Santamaria and the Movement. ‘I abhor censorship’, Mannix said, but he withdrew it from sale at the Cathedral.

It is hard to gauge the legacy of all this. It stopped the Labor Party giving us governments of the Left, but then for a long time it stopped it giving us governments at all. And it was in Sydney, relatively free from the reach of Mannix and Santamaria, that Catholics came to have such influence in the Right of the Labor Party. It is hard to see how much Daniel Mannix would have recognised in Paul Keating, the most high-flying of them all – the street fighter, perhaps.

Brenda Niall acknowledges the vividness of all this political power and glory, but it is ultimately the enigma of the man that commands her attention. When Mannix was told that Paul VI had been elected Pope, he said:

I believe he remembers me. I can’t say I remember him. But that’s not surprising. After all … I was the Archbishop of Melbourne and he was just another Monsignor around the place.

Then he paused. ‘Now’s he’s come unto his own. And I’m still sittin’ on the shelf.’

This biography of Mannix is good at this sort of thing. Brenda Niall captures the Mannix who spoke, long before it was fashionable, of the wrongs, ‘witting and unwitting’, that were inflicted on the Aborigines. She tells the story of how Mannix, as president at Maynooth, was asked to fly the Union Jack and flew Edward VII’s racing colours instead. (Although Mannix used to repeat this story, it turns out not to be true.) She talks of his quite extraordinary submission to Vatican II in which he spoke of the dictates of

conscience … formed in good faith … which God Himself holds in respect and embraces in love, even if the gift of faith is no longer evident in it.

And Niall is surely right to cite Edmund Campion saying this was a very striking performance by a very old man at the end of his life.

For all his turbulence and glamour – the qualities that made Father Brosnan, the Pentridge priest, say Mannix was the only human being he had ever seen whom he couldn’t take his eyes off, and which made Clifton Pugh, who painted his portrait, say that the power of his presence was overwhelming – there was a great mildness in Daniel Mannix. It is typical that he should have taken Walter Burley Griffin’s weird Gaudí-esque modernist design for Newman College, just as it is typical that he should have sent Vincent Buckley and Max Charlesworth to study overseas. Typical, too, that Santamaria, who claimed to love him more than his own father, should have been his homme fatale, and that it was his sense of outrage at the wrongs done to Ireland that should have made him such a tower of an Australian.

But there was a humility in this man who soared alone like a steeple. When a zealous priest was preaching about the nine first Fridays (which were supposed to guarantee entry to heaven), Mannix said he thought it was a mercy that there were comparatively few things you were bound as a Catholic to believe. And when a fellow bishop said that Mannix would be more powerful dead than alive, Mannix replied: ‘That may console you, but I don’t see what it does for me.’

I remember the captivation of the interview Gerald Lyons did with Mannix: so close to death, so close to God, they said. What pride and modesty, what self-deprecation and what flaming rectitude this strange old Irishman had; and what a heightened sense of destiny, of power and glory, and intimations of an ancient sorrow, he gave to Australia. I am not old enough to have seen him, top-hatted and frock-coated, walk from ‘Raheen’ to St Peters, but I will never forget the man who rode like a prince in the cool afternoon light under that purple biretta in the open Rolls Royce. And years later I saw him, too, as a boy, his body lying in state, looking even then, newly dead, like a legend and a mystery.