‘You would be surprised,’ Joseph Kennedy said to his son John in 1940, ‘how a book that really makes the grade with high-class people stands you in good stead for years to come.’ At the time, Kennedy senior was pulling strings to have his second son’s thesis published. Years later, with an eye on the presidency, John F. Kennedy used his speech writer Theodore Sorensen to assist him as he drafted Profiles in Courage. It would become a bestseller, eventually (and controversially) wining a Pulitzer prize. The links between presidential aspirants and books is well-established. It has become more unusual in recent years for presidential candidates not to have written books, usually in the form of memoirs, policy works, or some combination of both.

In Kennedy’s day, presidential candidates were chosen by party powerbrokers in proverbial smoke-filled rooms, with little input from voters. Starting with reforms in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the primary process became crucial in determining a party’s nominee. These reforms have extended the primary season beyond the actual primaries themselves to what is referred to as the ‘invisible primary’, which starts almost a year before the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary and nearly two years before the general election in November. Candidates need to distinguish themselves quickly writing a memoir is one way to do so.

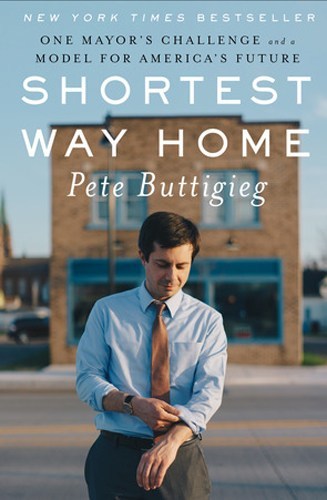

Unusual candidates early in the invisible primary have become a cliché. How far they can advance can no longer be predicted. A half-Kenyan, half-white man whose middle name is Hussein and a loudmouthed former reality television star with no political experience should not have advanced far in the nominating process. This immediate past history of unlikely candidates is what makes, in part, Pete Buttigieg so compelling a candidate. Pete Buttigieg, or ‘Mayor Pete’ as the press have dubbed him, has a story with a multiplicity of unconventional features. Raised in a deeply left-wing, intellectual household by a mother from Texas, and a father from Malta, Buttigieg was part of the generation defined by the terrorist attacks on 9/11. When he attended Harvard, he lived close to another history-altering event: the creation of Facebook. Buttigieg is young. At 37, he is the youngest serious candidate for a major party’s nomination since William Jennings Bryan in 1896. He is a military veteran. He is a Rhodes Scholar. And he is the first openly gay candidate to have a pathway to the highest office in the United States.

Buttigieg’s memoir Shortest Way Home: One Mayor’s Challenge and a Model for America’s Greatness displays its purpose via the cover image. Buttigieg’s eyes are downcast (humble), but he’s rolling up his sleeves (ready to get to work and clean up America). The backdrop is Western Avenue, in his home town of South Bend, Indiana, but it’s slightly blurred in a fashion that implies ‘Anytown, USA.’ This background becomes the foreground in his memoir. The ‘newsworthy’ parts of his story – his military service and his sexuality – come later. Urban renewal, and how that can be accomplished, leads. In the aftermath of 2016, where populist policies were aimed at a dying industrial heartland, the story about the transformation of South Bend will have particular resonance. Buttigieg writes movingly about ‘the tragedy encoded in’ the ‘widespread plague of empty factory buildings’ that occupied his town during his youth. Chapter Seven of the memoir, entitled ‘Monday Morning: A Tour’ tracks the changes he facilitated during his time as mayor. It is evocative stuff. And through the narrative of the transformation of his town Buttigieg is able to weave observations on the Iraq war, on Obama and Sanders, Pence and Trump. There is a mordant wit as he discusses war and receiving his dog tags:

I’d been told to separate the two tags I’d been issued. ‘Do your family a favour,’ someone had said, showing me how to lace one tag into one of my combat boots, while the others stayed around my neck. That way they could figure out who you had been even if your leg wound up in a different place than the rest of you.

Returning from a conference in Sydney in mid-August I got chatting to my taxi driver, who was garrulous even by the standards of his profession. Discussing the large field of Democratic candidates, he asked who I thought would get the nomination, then huffed at my response.

‘Pocahontas? Doesn’t stand a chance.’

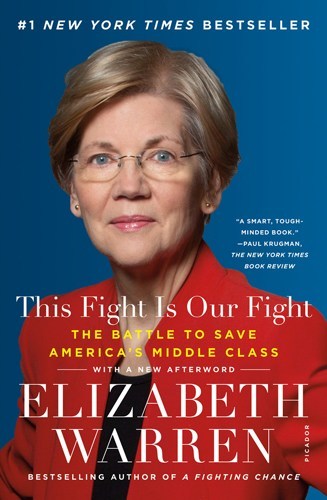

He was referring to the infamous exchanges Elizabeth Warren has had with Donald Trump over questions about her ancestry, exchanges derived from Warren’s claims of Native American descent during her career as a Harvard law professor. It remains to be seen whether Warren can move past the issue in the general election if she gets the Democratic nomination. This Fight is Our Fight: the Battle to Save America’s Middle Class, however, is a formidable mixture of personal narrative and wonkish detail. Unlike many of the other potential nominees, Warren has written a number of serious policy books, and This Fight draws upon her pre-Senate academic research on banks. This work in post-GFC Washington catapulted her into the Senate, as she gained a national profile for her assistance with the Emergency Economic Stabilisation Act in 2008, and the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. While the subject area may seem dry, it is a story Warren tells capably, placing it in the broader historical context of Franklin Roosevelt’s fight to keep capitalism under control, and her own family’s struggle to remain above the poverty line.

At times a forced folksiness can distract the reader away from Warren’s critiques of banks and the financial system in general:

I’m happy that the GDP is up and unemployment is down. Yay!…Meanwhile, banks are still Too Big to Fail. Actually, some are bigger than ever, or So Big We Can’t Let Them Stub Their Little Toesies.

In an era where politicians declaim that we have ‘had enough of experts’, it is disappointing to see Warren pivot this way, as if she is afraid of appearing too smart. Her analysis of the impact of financial deregulation on black and Latino minorities is excellent, and her assessment of how difficult it is for minority families in the housing market also allows her to get another shot in at Donald Trump:

Years after the financial crash, signs of housing discrimination persist…and this sort of discrimination has been going on a long time: favouring white renters while turning away black renters…is pretty much what was happening in some of President Trump’s apartment buildings back in the 1960s and 1970s – and which ultimately resulted in a settlement with the Department of Justice.

This ‘two-birds with one stone’ in tackling substantive issues and Trump at the same time makes for an engaging read, and is an approach that will serve Warren well in the general election if she wins the nomination.

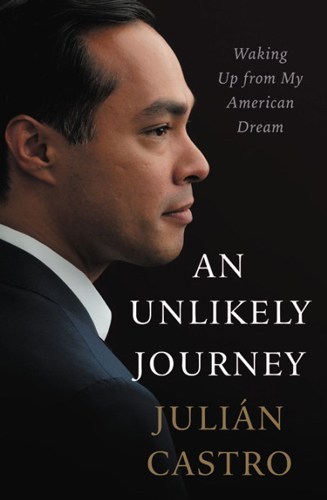

As I neared Ursula [South Texas], my thoughts kept returning to my grandmother, Mamo. Psychologists warn of the trauma suffered by kids who are separated from their families… Even at age seventy, Mamo had still wept uncontrollably as she remembered being pulled from her dying mother and told that she was going to live with another family in the United States… the circumstances of that border crossing, though certainly different from the experiences of the children whom I hope to visit, had left a lasting impact on her life.

On the first pages of his memoir An Unlikely Journey: Waking Up from My American Dream Julian Castro, former mayor of San Antonio and Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under Barack Obama, nails his colours to the mast. He is travelling to a processing centre about a mile from the border to ‘protest the Trump administration’s policy of removing children from parents who had been apprehended at the border’. These border policies, and the experience of growing up Hispanic in Texas, form the heart of Castro’s narrative. Like Buttigieg and Warren, he intertwines his life story with a major area of policy: that of US/Mexican border policy and the treatment of Latino Americans.

In contrast to more silver-tailed candidates, Castro and his twin brother Joaquin, who is currently serving in the US House of Representatives, came from a genuinely poor background. Their parents were political activists, with views forged in the cauldron of 1960s Chicano politics, a civil rights movement that focussed on the ‘forgotten minority’ of Hispanic-Americans. Castro does not shy away from the personal details of his parent’s life, and their early life together as a family. His father was still married to another woman when he began a relationship with Castro’s mother Maria. Maria herself developed a drinking problem, one that the sons had to confront directly at a young age. Money was a perennial problem, especially when the boys’ parents separated. Mamo, suffering diabetic ill-health when she moved in with Maria and the boys, attempted suicide. Throughout these struggles, Castro records the brothers’ keen sense to ‘get out’, and strive for a greater life. This striving would lead at times to intense rivalry between the two, an interesting dynamic to consider as they have both moved into the political arena.

Julian Castro’s story nearly took an historic turn in 2016 when he was being considered for the VP slot next to Hillary Clinton. He is diplomatic when discussing her eventual choice of Tim Kaine, but there is clear criticism implied in the line, ‘she probably figured that since she was way ahead, there was no point taking a risk when she didn’t have to’. Castro admits that in terms of his own chances in earlier political races his ‘youthfulness could be used against me’, – and indeed there is little to indicate the same issue would not arise again if the nomination goes to him.

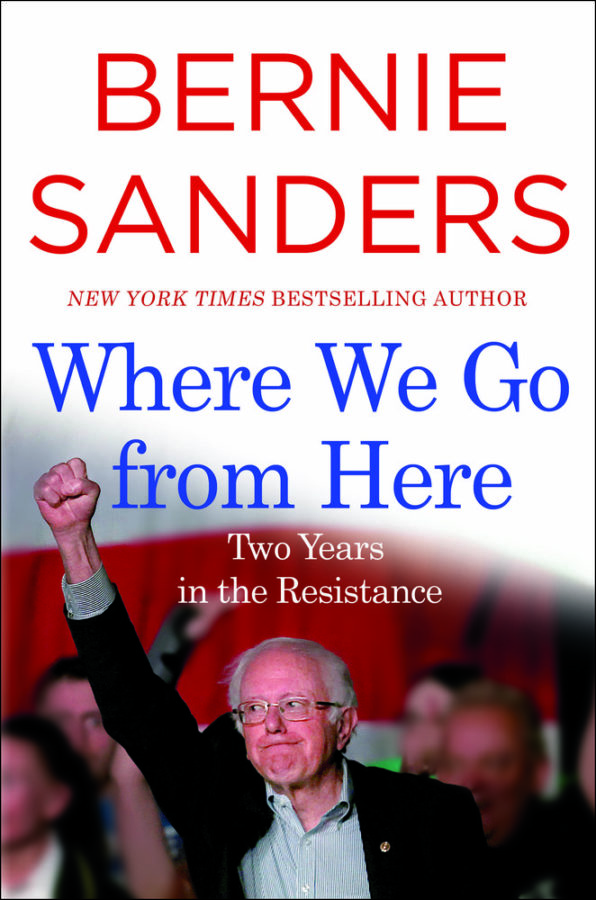

It was one of the surprise stories of the invisible primary in 2016. After failing to win the nomination in 2008 from a young, charismatic candidate, Hillary Clinton – former first lady, former senator, and former Secretary of State – was to be crowned the Democratic nominee, and shortly afterwards president. No-one was expecting a serious primary challenge, least of all from an obscure, 75-year-old Vermont senator who described himself as a socialist and had always run as an independent, not a Democrat. Yet Bernie Sanders mounted a challenge that invigorated the left-wing base of the Democratic party suspicious of the ever-triangulating Clinton. While unclear how much this challenge cost her in the general, it is plain from the resentful, deeply conflicted tone of Where We Go From Here: Two Years in the Resistance that the primary fight with Hillary, and what he could have done differently in the general election in 2016, is still very much on Sanders’ mind.

Unlike the other memoirs covered here, Where We Go From Here is not a coherent narrative of a candidate’s life, and their particular policy issues. Sanders is a top-tier candidate, but that’s hardly conveyed in this unfocussed, grab-bag collection of columns, speeches, and new material. Sanders skips around various different policy issues, most of which were fairly radical in 2016, but seem less so in 2019. Sanders has shifted the debate, but he seems unwilling to exit the stage and leave the nomination for a younger, more appealing candidate.

In part, this reluctance stems from his narcissism, which is apparent in book. He would never make claims for himself, of course, merely let others do the talking. On page 84 the reader will find Sanders in Europe, quoting a Newsweek article:

Sanders…has long been popular in Europe. In the Democratic primary against Hillary Clinton, he won more than 60 percent of the vote in Germany, France, Spain, and the United Kingdom. The reasons for this popularity are not hard to fathom…

What is hard to fathom is why Sanders feels the need to point this out two years after the conclusion of said primary. Still not finished, he continues:

It was pointed out that my remarks in Berlin had a bit of historical context. In June 1963, President John F. Kennedy gave a major speech just outside the auditorium where I spoke. I was proud to have followed in his footsteps when speaking about the need for U.S.-European unity.

It is unclear whether it was Newsweek that ‘pointed out’ the JFK comparison, or someone else. But it illustrates the strategy deployed throughout this book. When policy is dealt with, it is cursory: Medicare for All, electoral reform. Sanders depicts himself as an outsider in Washington, but makes time to praise senators Harry Reid and Chuck Schumer, hardly the most progressive voices in Congress. A shout-out to congressional allies is no flaw, yet hardly contributes to the notion that Sanders is a different sort of politician. Where We Go From Here could have been a better, more coherent work. As it stands, it may well provide a monument to political hubris.

And finally, Joe Biden. A decades-long career in the senate, two previous failed attempts at the Democratic nomination in 1988 and 2008, and a star turn as Barack Obama’s vice-president have brought Biden to this moment, his last chance at the nomination and the presidency itself. Many have argued that Biden’s last chance was actually in 2016. A primary fight with Clinton and Sanders would have been damaging, but Biden’s blue-collar appeal combined with his status as a Democratic insider may have split the difference between Sanders and Clinton, providing an opponent for Trump who could have won in crucial states like Wisconsin and Michigan.

What prevented a run in 2016 was the death of his beloved son Beau, which forms the basis for Promise Me, Dad: A Year of Hope, Hardship, and Purpose. I wrote about this book in 2017 and wondered then if Biden was conceding that his political career was over. It clearly wasn’t, and Biden’s pursuit of the Democratic nomination provides a new context for this memoir. It remains a moving account of Beau Biden’s illness and death. Obama features prominently across these pages. But how the Obama legacy can be grappled with in the age of Trump is a question that many of the Democratic candidates seem to be struggling with. A popular figure amongst the Democratic base, he still remains divisive across the country as a whole. Biden balances these two points well in 2016, providing a decent character assessment of Obama:

The president had the further benefit of near absolute self-sufficiency; unlike most people I know, his sense of self-worth seemed entirely independent of what other people thought of him. He was almost never ruffled by the slights and unfair criticisms I saw him endure.

At the same time, tension is revealed when Biden recalls the discussions around the 2016 nomination, and how Obama had ‘subtly weighed in against’ Biden running. While the issue was centred around the Clinton candidacy, the reader and/or potential voter may feel entitled to ask the obvious question: if Obama didn’t think Biden should run in 2016, why should he run in 2020?

It is still unclear at the time of writing who the nominee for the Democrats will be. There are more candidates and more candidate memoirs than I’ve covered here. It is clear, from Donald Trump’s numerous jabs at the front-runners that the 2020 presidential election will be just as vicious and sordid as 2016. Some of these books will undoubtedly wind up in remainder bins, and by next year readers may struggle to remember who some of these politicians were. Pete Buttigieg’s Shortest Way Home: One Mayor’s Challenge and a Model for America’s Greatness may well stand the test of time, not just on quality but on his standing as a future leader of the Democratic party. This Fight is Our Fight may also achieve longevity for its policy detail and depth. In the meantime, these memoirs serve as a reminder of the life journeys of politicians, of the evolution of their convictions and policy positions – before the mud-slinging of the general election campaign begins.